A PODICEPS PRIMER by Matthew L. Pelikan Wintertime Grebes Lack

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(82) FIELD NOTES on the LITTLE GREBE. the Following Observations on the Little Grebe (Podiceps R. Ruficollis) Were Made at Fetch

(82) FIELD NOTES ON THE LITTLE GREBE. BY P. H. TRAHAIR HARTLEY. THE following observations on the Little Grebe (Podiceps r. ruficollis) were made at Fetcham Pond, near Leatherhead, in Surrey, during the last three years. TERRITORY. Little Grebes begin to defend territories in the middle of February. These are small areas—about |- acre—situated in the parts of the very shallow lake that are overgrown with marestail (Hippuris vulgaris). Where several territories border on an open space, free from weeds, this constitutes a neutral area where paired birds can meet and associate with others, without fighting. The actual territories are strictly protected. Both sexes defend their borders, sometimes working together. Terri torial demonstrations-—far more often than not they do not end in actual fighting—take place many times daily between pairs whose marches adjoin. One bird makes a series of short rushes towards his neighbours' territory, flapping his raised wings, and keeping his head and neck outstretched ; at the same time he utters the shrill, tittering call. The owner of the territory advances in the same set style ; between each rush, both birds float with heads drawn in, flank feathers fluffed out, and wings slightly raised. So they approach each other, until they float about a foot apart, and strictly on the territorial border. As they face one another, I have seen one, or both birds peck with an almost nervous movement at the surface of the water, as though picking something up. On one occasion the bird which had started the encounter splashed the water with its beak, and snatched at a weed stem. -

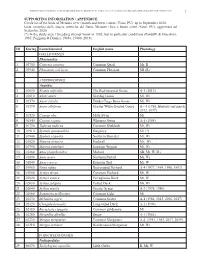

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Body Weights of Newly Hatched Anatidae.--As Early As 1928 (E

1965Oct. ] GeneralNotes 645 following day, Boulva found the bird again on the same territory, identified it posi- tively as a Le Conte's Sparrow (Passerherbuluscaudacutus), and photographed it with a 400 mm telephoto lens. On 23 July the second writer, after long observation, identified a Le Conte's Sparrow on the same territory. On 27 July Mr. Franqois Hamel, from "le Club des Ornithologues de Quebec," with Browne, had occasionto study the bird and its song; he too was convinced that the bird was a Le Conte's Sparrow. On 28 July both writers sighted two Le Conte's Sparrows together, captured one of the birds, and banded it (U.S.F.&W.S. band no. 52-39003, size 1). On 31 July, Mr. Raymond Cayouette, Curator of Birds at the Quebec Zoological Garden and President of "le Club des Ornithologuesde Quebec," with the Reverend Robert Plante of the same club, botb accompaniedby the first writer, were able to study the sparrow and were satisfied with the identification. On 11 August Browne caught a young Le Conte's Sparrow incapable of flight and banded it (band no. 103-42113, size 0), while two adults, one seen to be banded, were flying about. The young bird was well-feathered but had some down adhering to the plumage. The primaries were full grown except for the two outermost (pri- maries 8 and 9), which were short and still sheathed at the base. The tail feathers were well grown and pointed. The plumage was typical of the juvenal plumage of the species(see T. -

BREEDING of the LITTLE GREBE by G

THE S.A. ORNITHOLOGIST 109 BREEDING OF THE LITTLE GREBE By G. CLARKE. The following is a brief synopsis of events, continuously an agitated 'clip' or 'jip', a not altogether complete, of the breeding of single note. The nest was found to be a pair of Little Grebe (Podiceps nouaehol placed between a few sapling eucalypts 2 landiae) on the main dam at the Para Wirra to 3 feet in height, standing in the water, National Park, 20 miles NNE of Adelaide and was composed mainly of rush stems in the Mt. Lofty Ranges. (funcus) 'anchored' between the. saplings and The dam occupies an area of some two resembling a pile of. debris. The nest con and a half acres, and is situated at an tained three eggs, stained an ochrous yellow. altitude of approximately 900 ft. a.s.l, in November 20: Both adults with two young Savannah Woodland, comprised mainly of noted. Water level 8 inches below the spill the Blue Gum, Eucalyptus leucoxylon. The way wall. dam wall is formed by an earth bank and November 23: Two adults; the young as it has been placed across a creekbed the were not seen. resultant shape of the dam is a long narrow December 1: Both adults were noted carry triangle with one small inlet on its northern ing material to a new nest site. Only one side formed by a second, smaller creek. The young bird seen. W.L. 12 inches below walL depth of the water at the deepest point is approximately 8 to 10 feet, and the appro December 12: One bird sitting on the priate levels below the spillway wall are second nest, leaving only when approached given. -

Grebe, Red-Necked

Grebes — Family Podicipedidae 101 Red-necked Grebe Podiceps grisegena Winter: One was at Sweetwater Reservoir (S12) 20 December 1969–2 January 1970 (AFN 24:538, 1970), one Uncommon as a winter visitor even in coastal was at the south end of San Diego Bay (V10) 14 March northern California, the Red-necked Grebe is casual 1977 (AB 31:372, 1977), and one was at Santee Lakes (P12) as far south as San Diego County, where there are 30 December 1984–6 January 1985 (D. and N. Kelly, AB three well-supported records. These are the south- 39:209, 1985). Other published reports from the 1950s ernmost for the species along the Pacific coast; the and 1960s are more likely of misidentified Horned Grebes Red-necked Grebe is unknown in Mexico. (Unitt 1984). Eared Grebe Podiceps nigricollis Grebe winters by the thousands. Though the grebe Though highly migratory, the Eared Grebe is also is still common on both fresh and salt water else- flightless for much of the year; its breast muscles where, the numbers are much smaller. As a breeding atrophy except when needed for migration. Breeding bird the Eared Grebe is rare and irregular in San birds use ponds and marshes with fresh to brackish Diego County, which lies near the southern tip of water, but nonbreeders concentrate in water that is the breeding range. hypersaline. In San Diego County, such conditions Winter: The salt works at the south end of San Diego Bay are found in south San Diego Bay, where the Eared are the center for the Eared Grebe in San Diego County. -

An Avian Quadrate from the Late Cretaceous Lance Formation of Wyoming

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 20(4):712-719, December 2000 © 2000 by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology AN AVIAN QUADRATE FROM THE LATE CRETACEOUS LANCE FORMATION OF WYOMING ANDRZEJ ELZANOWSKll, GREGORY S. PAUV, and THOMAS A. STIDHAM3 'Institute of Zoology, University of Wroclaw, Ul. Sienkiewicza 21, 50335 Wroclaw, Poland; 23109 N. Calvert St., Baltimore, Maryland 21218 U.S.A.; 3Department of Integrative Biology, University of California, Berkeley, California 94720 U.S.A. ABSTRACT-Based on an extensive survey of quadrate morphology in extant and fossil birds, a complete quadrate from the Maastrichtian Lance Formation has been assigned to a new genus of most probably odontognathous birds. The quadrate shares with that of the Odontognathae a rare configuration of the mandibular condyles and primitive avian traits, and with the Hesperomithidae a unique pterygoid articulation and a poorly defined (if any) division of the head. However, the quadrate differs from that of the Hesperomithidae by a hinge-like temporal articulation, a small size of the orbital process, a well-marked attachment for the medial (deep) layers of the protractor pterygoidei et quadrati muscle, and several other details. These differences, as well as the relatively small size of about 1.5-2.0 kg, suggest a feeding specialization different from that of Hesperomithidae. INTRODUCTION bination of its morphology, size, and both stratigraphic and geo- graphic occurrence effectively precludes its assignment to any The avian quadrate shows great taxonomic differences of a few fossil genera that are based on fragmentary material among the higher taxa of birds in the structure of its mandibular, without the quadrate. -

Great Crested Grebe Podiceps Cristatus in Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu

120 Indian BIRDS VOL. 14 NO. 4 (PUBL. 23 OCTOBER 2018) Bristled Grassbird Chaetornis striata: A pair of Grassbirds was George, A., 2018. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S43199767. [Accessed seen on 24 February 2018, photographed [119] on 26 February, on 13 August 2018.] and seen on the subsequent day as well. This adds to the recent George, P. J., 2015. Chestnut-eared Bunting Emberiza fucata from Ezhumaanthuruthu, Kuttanad Wetlands, Kottayam District. Malabar Trogon 13 (1): 34–35. knowledge on its wintering status in Karnataka. Other records Harshith, J. V., 2016. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S33278635. are from Dakshin Kannada (Harshith 2016; Kamath 2016; [Accessed on 13 August 2018.] Viswanathan 2017), Mysuru (Vijayalakshmi 2016), and Belgaum Kamath, R., 2016. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S33148312. [Accessed (Sant 2017). on 13 August 2018.] Lakshmi, V., 2015. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S21432671. [Accessed on 13 August 2018.] Monnappa, B., 2012. Website URL: https://www.indianaturewatch.net/displayimage. php?id=317526. [Accessed on 14 August 2018.] Nair. A. 2018. Website URL: https://ebird.org/view/checklist/S43311515. [Accessed on 13 August 2018.] Naoroji, R., 2006. Birds of prey of the Indian Subcontinent. Reprint ed. New Delhi: Om Books International. Pp. 1–692. Narasimhan, S. V., 2004. Feathered jewels of Coorg. 1st ed. Madikeri, India: Coorg Wildlife Society. Pp. 1–192. Orta, J., Boesman, P., Marks, J. S., Garcia, E. F. J., & Kirwan, G. M., 2018. Western Marsh- harrier (Circus aeruginosus). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D. A., & de Juana, E., (eds.). -

Pied-Billed Grebe (Podilymbus Podiceps) Damon Mccormick

Pied-billed Grebe (Podilymbus podiceps) Damon McCormick Washington. 6/16/2008 © Jerry Jourdan (Click to view a comparison of Atlas I to II) To early naturalists it was the “hell-diver” or limit of the species’ range, “it nests abundantly in every suitable place in the state, from the “water-witch”, and its idiosyncrasies tended to Ohio-Indiana line to Lake Superior.” inspire hyperbole: “These peculiar little spirits Subsequent surveys in the 20th Century of the water present a very radical departure however, recorded decidedly less than abundant from what the word ‘bird’ usually brings to densities in the NLP and UP, and MBBA I mind” (Rockwell 1910). Occupying its own documented a significantly higher percentage of genus within the seven-member North breeding Pied-billed Grebes in the SLP, American Podicipedidae family, the Pied-billed particularly in southwestern counties (Storer Grebe, while by no means singularly non-avian, 1991). was not mischaracterized by its antiquated appellations. With a pattern of nocturnal Breeding Biology migration and a propensity to dive rather than Pied-billed Grebes tend to occupy fresh to fly in response to threats, the species is almost moderately brackish waterbodies greater than exclusively encountered upon the marshes and 0.2 ha, marked by dense stands of emergent ponds that constitute its summer home vegetation and ample stretches of open water (Wetmore 1924, Muller and Storer 1999). A (Muller and Storer 1999). Their cuckoo-like breeding adult, diminutive and drably adorned song – “far-carrying, vibrant, throaty barks” – in brown and gray, nonetheless demonstrates a can be vocalized by both sexes, and is strident territoriality within its wetland turf, associated with courtship and territorial responding aggressively to both intra- and inter- delineation (Deusing 1939, Muller and Storer specific interlopers (Glover 1953, McAllister 1999, Sibley 2000). -

The Decline and Probable Extinction of the Colombian Grebe Podiceps Andinus

Bird Conservation International (1993) 3:221-234 The decline and probable extinction of the Colombian Grebe Podiceps andinus J. FJELDSA Summary Searches were made for the Colombian Grebe Podiceps andinus in 1981 in the wetlands in the Eastern Andes of Colombia. The studies also included surveys of other waterbirds and recorded the general conditions of these wetlands, once the stronghold for waterbirds in the northern Andes. The Colombian Grebe was apparently last seen in 1977 in Lake Tota, and is probably extinct, although a flock may have been moving around outside Lake Tota and could have settled outside the former breeding area. The primary reason for the decline must be draining of wetlands and eutrophication and siltation which destroyed the open submergent Potamogeton vegetation, where this grebe may have been feeding on a large diversity of arthropods. Introduction of exotic fish and hunting may also have played a role. Durante 1981 se han realizado varias expedidones en busca de Podiceps andinus en las zonas hiimedas de los Andes Orientales de Colombia. Durante estos estudios tambien se censaron otras aves acuaticas y se tomaron notas sobre el estado general de estas zonas humedas, que en el pasado fueron el principal enclave para las aves acuaticas en los Andes del Norte. Aparentemente Podiceps andinus fue visto por ultima vez en 1977 en el Lago Tota, y esta probablemente extinguido, aunque podrfa haber un bando en las inmediaciones de dicho lago que se hay a establecido fuera de la antigua area de cria. La razon fundamental del declive debe ser el drenaje de las zonas humedas y la eutrofiz- acion y salinizacion que ha destruido la vegetation sumergida de Potamogeton, donde esta especie se alimentaba de una gran variedad de artropodos. -

33. the Courtship Habits of the Great Crested Grrebe (Podiceps

PROCEEDINGS OF TlIE GENERAL MEETINGS FOR SCIENTIFIC BUS ESS OF TIlfi ZOOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF LONDON. PAPERS. 33. The Courtship - habits * of the Great Crested Grebe (Podiceps c~istatus); with an addition to the Theory of Sexual Selection. By JULXANS. HUXLEY,B.A., Professor of Biology in the ltice Iiistitute, Houston, Texas t. [Received March 14, 1914: Read April 21,19141 (Plates: I. & 11.:) INDEX. I. GENERALPART. Page 1. Introduction ......................................................... 492 2. Appearance. ............ ............................................. ... 492 3. Annual History ...................................................... 495 4. Some Descriptions ................................................... 496 5. The Itelations of the Sexes. (i.) The act of pairing .......................................... 60 1 (ii.) Courtship ................................................... 608 (iii.) Nest-building ...................................... 617 (iv.) Relations of ditferent pairs .................... 521 (v.) Other activities ..................................... 622 6. Discussion ................................................... 622 __- _______ X It was not until this paper was in print that I realized that the word Courtship is perliaps mislending ax applied to the incidents here recorded. While Courtship s-d, strictly speaking, denote only ants-nuptial hehavionr, it may readily be extended to include any behaviour by which an orga!iism of one sex seeks to “ win over’’ one of the opposite sen. will be seen that the behaviour of the Grebe cannot be included under this. Love-habitas” would bo a better term in snme ~ayli;for the present, however, it is sufficient to point out the inadequacy of the present biological terminology. t Conimnnicated hy the SECRETARY. z For enplanntion of the PlateR see 1). 561. PHOC.ZOOL. S0C.-1914, NO.YYXV. 35 4!)5 3111. d. s. III:xLIsY ox TIIE 11. sl-IKI.\l>T’AIlT. 7. I,ocalit~,iiietliods, rtc. -

And Red-Necked Grebes (Podiceps Grisegena)

Changes to the Population Status of Horned Grebes ( Podiceps auritus ) and Red-necked Grebes ( Podiceps grisegena ) in Southwestern Manitoba, Canada GORD HAMMELL P.O. Box 37, Erickson, Manitoba R0J 0P0 Canada; email: [email protected] Hammell, Gord. 2017. Changes to the population status of Horned Grebes ( Podiceps auritus ) and Red-necked Grebes ( Podiceps grisegena ) in southwestern Manitoba, Canada. Canadian Field-Naturalist 131(4): 317–324. https://doi.org/10.22621/ cfn. v131i4.2069 Continental trend data for North America suggest that Horned Grebe ( Podiceps auritus ) breeding populations are declining and Red-necked Grebe ( P. grisegena ) populations are increasing. However, data reliability is low due to lack of survey routes in the northern boreal and taiga ecozones, areas encompassing much of the breeding range of both species. Locally in the southern Manitoba prairie ecozone, reliability of long-term trend data is also considered low and these data suggest that Horned Grebe populations are declining faster than the continental trend and that Red-necked Grebe populations are increasing rapidly. The lack of current quantitative information on population densities of these two species in southern Manitoba prompted me to compare 1970s historical data from two sites to recent data collected at the same locations in 2008–2016. I surveyed 42 (1970–1972) and 38 (2008–2016), and 144 (2009–2015) Class III-V wetlands at Erickson and Minnedosa, Manitoba, respectively. Historical Minnedosa data were available from previous field studies. At both locations, Horned Grebe breeding populations have fallen significantly, and Red-necked Grebe populations have risen significantly since the 1970s. The results of this study corroborate the Breeding Bird Survey’s trend data for Horned and Red-necked Grebes in southwestern Manitoba pothole habitat. -

Birds of Indiana

Birds of Indiana This list of Indiana's bird species was compiled by the state's Ornithologist based on accepted taxonomic standards and other relevant data. It is periodically reviewed and updated. References used for scientific names are included at the bottom of this list. ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* Anseriformes Anatidae Dendrocygna autumnalis Black-bellied Whistling-Duck Waterfowl: Swans, Geese, and Ducks Dendrocygna bicolor Fulvous Whistling-Duck Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose Anser caerulescens Snow Goose Anser rossii Ross's Goose Branta bernicla Brant Branta leucopsis Barnacle Goose Branta hutchinsii Cackling Goose Branta canadensis Canada Goose Cygnus olor Mute Swan X Cygnus buccinator Trumpeter Swan SE Cygnus columbianus Tundra Swan Aix sponsa Wood Duck Spatula discors Blue-winged Teal Spatula cyanoptera Cinnamon Teal Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mareca strepera Gadwall Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mareca americana American Wigeon Anas platyrhynchos Mallard Anas rubripes American Black Duck Anas fulvigula Mottled Duck Anas acuta Northern Pintail Anas crecca Green-winged Teal Aythya valisineria Canvasback Aythya americana Redhead Aythya collaris Ring-necked Duck Aythya marila Greater Scaup Aythya affinis Lesser Scaup Somateria spectabilis King Eider Histrionicus histrionicus Harlequin Duck Melanitta perspicillata Surf Scoter Melanitta deglandi White-winged Scoter ORDER FAMILY GENUS SPECIES COMMON NAME STATUS* Melanitta americana Black Scoter Clangula hyemalis Long-tailed Duck Bucephala