Observation on the Great Grebe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birds of Bharatpur – Check List

BIRDS OF BHARATPUR – CHECK LIST Family PHASIANIDAE: Pheasants, Partridges, Quail Check List BLACK FRANCOLIN GREY FRANCOLIN COMMON QUAIL RAIN QUAIL JUNGLE BUSH QUAIL YELLOW-LEGGED BUTTON QUAIL BARRED BUTTON QUAIL PAINTED SPURFOWL INDIAN PEAFOWL Family ANATIDAE: Ducks, Geese, Swans GREATER WHITE-FRONTED GOOSE GREYLAG GOOSE BAR-HEADED GOOSE LWSSER WHISTLING-DUCK RUDDY SHELDUCK COMMON SHELDUCK COMB DUCK COTTON PYGMY GOOSE MARBLED DUCK GADWALL FALCATED DUCK EURASIAN WIGEON MALLARD SPOT-BILLED DUCK COMMON TEAL GARGANEY NORTHERN PINTAIL NORTHERN SHOVELER RED-CRESTED POCHARD COMMON POCHARD FERRUGINOUS POCHARD TUFTED DUCK BAIKAL TEAL GREATER SCAUP BAER’S POCHARD Family PICIDAE: Woodpeckers EURASIAN WRYNECK BROWN-CAPPED PYGMY WOODPECKER YELLOW-CROWNED WOODPECKER BLACK-RUMPED FLAMBACK Family CAPITONIDAE: Barbets BROWN-HEADED BARBET COPPERSMITH BARBET Family UPUPIDAE: Hoopoes COMMON HOOPOE Family BUCEROTIDAE: Hornbills INDAIN GREY HORNBILL Family CORACIIDAE: Rollers or Blue Jays EUROPEAN ROLLER INDIAN ROLLER Family ALCEDINIDAE: Kingfisher COMMON KINGFISHER STORK-BILLED KINGFISHER WHITE-THROATED KINGFISHER BLACK-CAPPED KINGFISHER PIED KINGFISHER Family MEROPIDAE: Bee-eaters GREEN BEE-EATER BLUE-CHEEKED BEE-EATER BLUE-TAILED BEE-EATER Family CUCULIDAE: Cuckoos, Crow-pheasants PIED CUCKOO CHESTNUT-WINGED CUCKOO COMMON HAWK CUCKOO INDIAN CUCKOO EURASIAN CUCKOO GREY-BELLIED CUCKOO PLAINTIVE CUCKOO DRONGO CUCKOO ASIAN KOEL SIRKEER MALKOHA GREATER COUCAL LESSER COUCAL Family PSITTACIDAS: Parrots ROSE-RINGED PARAKEET PLUM-HEADED PARKEET Family APODIDAE: -

The Penguin-Dance of the Great Crested Grebe

NOTES The Penguin-dance of the Great Crested Grebe.—The Editors have asked me to comment briefly on the remarkable photograph of the Penguin-dance of the Great Crested Grebe (Podiceps cristatus) published in this issue (plate 48). Comparatively few observers have been fortunate enough to "witness this elaborate form of courtship which has rarely been photographed, being the least often performed of this species' four main ceremonies (first described fully and named by J. S. Huxley in Proc. Zool. Soc. London, 1914, pp. 491-562). As in the far more common Head- shaking, the male and female grebe play identical r61es in the Penguin-dance, whereas in the Discovery and the "Display" ceremonies the rdles are different though interchangeable. Penguin-dancing usually occurs in the vicinity of the nest-site, within the territory of the pair, and is almost invariably preceded and followed by a long bout of intense Head-shaking in which Habit-preening is absent. The two birds dive and, while submerged, collect a bill-full of ribbony water-weed. On emergence, they swim towards each other with their tippets fully spread and, when quite close, both rear up out of the water simultaneously. They then meet breast to breast with only the very end of the body in the water, feet splashing to keep up, as shown in the photograph. As they sway together thus for a few seconds, they waggle their heads, gradually dropping the weed. After the normal Head-shaking which follows, the pair sometimes swim to the nest-platform where soliciting and copulation may occur. -

(82) FIELD NOTES on the LITTLE GREBE. the Following Observations on the Little Grebe (Podiceps R. Ruficollis) Were Made at Fetch

(82) FIELD NOTES ON THE LITTLE GREBE. BY P. H. TRAHAIR HARTLEY. THE following observations on the Little Grebe (Podiceps r. ruficollis) were made at Fetcham Pond, near Leatherhead, in Surrey, during the last three years. TERRITORY. Little Grebes begin to defend territories in the middle of February. These are small areas—about |- acre—situated in the parts of the very shallow lake that are overgrown with marestail (Hippuris vulgaris). Where several territories border on an open space, free from weeds, this constitutes a neutral area where paired birds can meet and associate with others, without fighting. The actual territories are strictly protected. Both sexes defend their borders, sometimes working together. Terri torial demonstrations-—far more often than not they do not end in actual fighting—take place many times daily between pairs whose marches adjoin. One bird makes a series of short rushes towards his neighbours' territory, flapping his raised wings, and keeping his head and neck outstretched ; at the same time he utters the shrill, tittering call. The owner of the territory advances in the same set style ; between each rush, both birds float with heads drawn in, flank feathers fluffed out, and wings slightly raised. So they approach each other, until they float about a foot apart, and strictly on the territorial border. As they face one another, I have seen one, or both birds peck with an almost nervous movement at the surface of the water, as though picking something up. On one occasion the bird which had started the encounter splashed the water with its beak, and snatched at a weed stem. -

Florida Field Naturalist PUBLISHED by the FLORIDA ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY

Florida Field Naturalist PUBLISHED BY THE FLORIDA ORNITHOLOGICAL SOCIETY VOL. 37, NO. 4 NOVEMBER 2009 PAGES 115-170 Florida Field Naturalist 37(4):115-120, 2009. FIRST RECORD OF LEAST GREBES (Tachybaptus dominicus) NESTING IN FLORIDA LEE M. HASSE AND O. DAVID HASSE 398 N.E. 24th Street, Boca Raton, Florida 33431 The Least Grebe (Tachybaptus dominicus), the smallest New World member of the grebe family (Podicipedidae), occurs from the southwestern United States and Mexico to Chile, Argentina and in the West Indies (Trinidad, Tobago, the Bahamas, and Greater Antilles; Ogilvie and Rose 2003). This is a plump grebe with yellowish eyes, a thin bill, and fluffy white tail coverts, ranging in length from 22-27 cm (8.25-10.5 inches). In basic plumage Least Grebes are brownish to blackish above with a white throat; in alternate plumage the throat is black. Their wetland habitats are varied and include fresh and brack- ish ponds, lakes, slow-flowing rivers, and mangrove swamps that have good vegetative cover along the edges. There are reports of nesting in temporary bodies of water (Storer 1992). Their compact floating nest is made of aquatic vegetation and anchored to rooted plants. The eggs are incubated by both adults and hatch in about 21 days (Palmer 1962). The Least Grebe is reported to nest year-round in the tropics. Although considered non-migratory, they have been found to move long distances (Storer 1992). Norton et al. (2009) report that the Least Grebe has been expanding its range in the Greater and Lesser Antilles in the last de- cade. -

![LOONS and GREBES [ ] Common Loon [ ] Pied-Billed Grebe---X](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1406/loons-and-grebes-common-loon-pied-billed-grebe-x-351406.webp)

LOONS and GREBES [ ] Common Loon [ ] Pied-Billed Grebe---X

LOONS and GREBES [ ] Common Merganser [ ] Common Loon [ ] Ruddy Duck---x OWLS [ ] Pied-billed Grebe---x [ ] Barn Owl [ ] Horned Grebe HAWKS, KITES and EAGLES [ ] Eared Grebe [ ] Northern Harrier SWIFTS and HUMMINGBIRDS [ ] Western Grebe [ ] Cooper’s Hawk [ ] White-throated Swift [ ] Clark’s Grebe [ ] Red-shouldered Hawk [ ] Anna’s Hummingbird---x [ ] Red-tailed Hawk KINGFISHERS PELICANS and CORMORANTS [ ] Golden Eagle [ ] Belted Kingfisher [ ] Brown Pelican [ ] American Kestrel [ ] Double-crested Cormorant [ ] White-tailed Kite WOODPECKERS [ ] Acorn Woodpecker BITTERNS, HERONS and EGRETS PHEASANTS and QUAIL [ ] Red-breasted Sapsucker [ ] American Bittern [ ] Ring-necked Pheasant [ ] Nuttall’s Woodpecker---x [ ] Great Blue Heron [ ] California Quail [ ] Great Egret [ ] Downy Woodpecker [ ] Snowy Egret RAILS [ ] Northern Flicker [ ] Sora [ ] Green Heron---x TYRANT FLYCATCHERS [ ] Black-crowned Night-Heron---x [ ] Common Moorhen Pacific-slope Flycatcher [ ] American Coot---x [ ] NEW WORLD VULTURES [ ] Black Phoebe---x Say’s Phoebe [ ] Turkey Vulture SHOREBIRDS [ ] [ ] Killdeer---x [ ] Ash-throated Flycatcher WATERFOWL [ ] Greater Yellowlegs [ ] Western Kingbird [ ] Greater White-fronted Goose [ ] Black-necked Stilt SHRIKES [ ] Ross’s Goose [ ] Spotted Sandpiper Loggerhead Shrike [ ] Canada Goose---x [ ] Least Sandpiper [ ] [ ] Wood Duck [ ] Long-billed Dowitcher VIREOS Gadwall [ ] [ ] Wilson’s Snipe [ ] Warbling Vireo [ ] American Wigeon [ ] Mallard---x GULLS and TERNS JAYS and CROWS [ ] Cinnamon Teal [ ] Mew Gull [ ] Western Scrub-Jay---x -

Identification and Distribution of Clark's Grebe

IDENTIFICATION AND DISTRIBUTION OF CLARK'S GREBE JOHN T. RA'Frl, Wildlife Biology, Washington State University, Pullman, Washington99164 For nearly 100 years ornithologists have considered the genus Aechmophorusto includeonly one species,the WesternGrebe (A. occiden- talis). Few ornithologists,especially amateur field ornithologists,have been aware that the WesternGrebe has been consideredpolymorphic, with two distinctphenotypes referred to as dark and light phases (Storer 1965, Mayr and Short 1970). Recent study of sympatricdark-phase and light-phasepopulations indi- catesthe polymorphismclassification is erroneousand that the forms func- tion as separate species(Ratti 1979). Additional data are needed on dark- phaseand light-phasebirds, and hopefullythis paper will aid in alertingboth professionaland amateurornithologists to the identificationand distribution of these species. LITERATURE REVIEW George N. Lawrence (in Baird 1858:894-895) originallydescribed the two grebeforms as separatespecies, calling the dark form the WesternGrebe (Podicepsoccidentalis) and the light form Clark'sGrebe (Podicepsclarkii). However, Coues (1874) and Henshaw (1881) suggestedthat the formswere color phases of the same species,and the American Ornithologists'Union (1886, 1931, 1957) classifiedthe forms as a singlespecies. Mayr and Short (1970:88) attributedthe variationto "scatteredpolymorphism." Both Storer (1965) and Lindvall (1976) reported assortativemating by WesternGrebes in Utah -- the tendencyof birdsto mate with individualsof the same phenotype. -

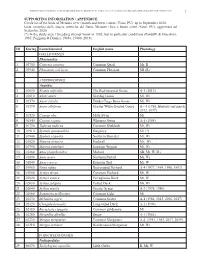

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Aberrant Plumages in Grebes Podicipedidae

André Konter Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae An analysis of albinism, leucism, brown and other aberrations in all grebe species worldwide Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae in grebes plumages Aberrant Ferrantia André Konter Travaux scientifiques du Musée national d'histoire naturelle Luxembourg www.mnhn.lu 72 2015 Ferrantia 72 2015 2015 72 Ferrantia est une revue publiée à intervalles non réguliers par le Musée national d’histoire naturelle à Luxembourg. Elle fait suite, avec la même tomaison, aux TRAVAUX SCIENTIFIQUES DU MUSÉE NATIONAL D’HISTOIRE NATURELLE DE LUXEMBOURG parus entre 1981 et 1999. Comité de rédaction: Eric Buttini Guy Colling Edmée Engel Thierry Helminger Mise en page: Romain Bei Design: Thierry Helminger Prix du volume: 15 € Rédaction: Échange: Musée national d’histoire naturelle Exchange MNHN Rédaction Ferrantia c/o Musée national d’histoire naturelle 25, rue Münster 25, rue Münster L-2160 Luxembourg L-2160 Luxembourg Tél +352 46 22 33 - 1 Tél +352 46 22 33 - 1 Fax +352 46 38 48 Fax +352 46 38 48 Internet: http://www.mnhn.lu/ferrantia/ Internet: http://www.mnhn.lu/ferrantia/exchange email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Page de couverture: 1. Great Crested Grebe, Lake IJssel, Netherlands, April 2002 (PCRcr200303303), photo A. Konter. 2. Red-necked Grebe, Tunkwa Lake, British Columbia, Canada, 2006 (PGRho200501022), photo K. T. Karlson. 3. Great Crested Grebe, Rotterdam-IJsselmonde, Netherlands, August 2006 (PCRcr200602012), photo C. van Rijswik. Citation: André Konter 2015. - Aberrant plumages in grebes Podicipedidae - An analysis of albinism, leucism, brown and other aberrations in all grebe species worldwide. Ferrantia 72, Musée national d’histoire naturelle, Luxembourg, 206 p. -

FEEDING BEHAVIOR of the LEAST GREBE (Tachybaptus Dominicus) UPON NEOTROPICAL RANIDS in COSTA RICA

Florida Field Naturalist 44(2):59-62, 2016. FEEDING BEHAVIOR OF THE LEAST GREBE (Tachybaptus dominicus) UPON NEOTROPICAL RANIDS IN COSTA RICA VÍCTOR J. ACOSTA-CHavES1,2,3 AND DANIEL JIMÉNEZ3 1Fundación Rapaces de Costa Rica, P.O. Box 1626-3000 Heredia, Costa Rica 2Escuela de Biología, Universidad de Costa Rica, San Pedro, Costa Rica E–mail: [email protected] 3Unión de Ornitólogos de Costa Rica, San José, Costa Rica Avian predation on amphibians can be considered an important evolutionary force for both taxa, and its documentation helps to elucidate aspects of evolution, ecology, and even conservation (Shea 1987, Wells 2010). But because these interactions are difficult to observe and quantify, the role of amphibians as dietary items of birds is still barely known in the Neotropics (Acosta and Morún 2014). For example, even when grebes (Podicipedidae) have been anecdotally reported to prey on aquatic amphibians (Shea 1987, Stiles and Skutch 1989, Kloskowski et al. 2010), data on habitat selection, diet, and feeding behavior of grebes are primarily from Old World and Nearctic regions (e.g., Shea 1987, Forbes and Sealy 1990, Wiersma et al. 1995, Kloskowski et al. 2010). In Neotropical areas, such as Costa Rica, both natural and artificial lagoons and ponds provide habitat for waterbirds, including grebes (Stiles and Skutch 1989). The Least Grebe (Tachybaptus dominicus) is a widespread waterbird ranging from the southern United States of America to northern Argentina, including the Bahamas and Greater Antilles. In Costa Rica the subspecies T. d. brachypterus is distributed from lowlands to 1525 m ASL, but it is most common in the Central Valley and San Vito Region (Stiles and Skutch 1989). -

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area

Common Birds of the Estero Bay Area Jeremy Beaulieu Lisa Andreano Michael Walgren Introduction The following is a guide to the common birds of the Estero Bay Area. Brief descriptions are provided as well as active months and status listings. Photos are primarily courtesy of Greg Smith. Species are arranged by family according to the Sibley Guide to Birds (2000). Gaviidae Red-throated Loon Gavia stellata Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: A small loon seldom seen far from salt water. In the non-breeding season they have a grey face and red throat. They have a long slender dark bill and white speckling on their dark back. Information: These birds are winter residents to the Central Coast. Wintering Red- throated Loons can gather in large numbers in Morro Bay if food is abundant. They are common on salt water of all depths but frequently forage in shallow bays and estuaries rather than far out at sea. Because their legs are located so far back, loons have difficulty walking on land and are rarely found far from water. Most loons must paddle furiously across the surface of the water before becoming airborne, but these small loons can practically spring directly into the air from land, a useful ability on its artic tundra breeding grounds. Pacific Loon Gavia pacifica Occurrence: Common Active Months: November-April Federal Status: None State/Audubon Status: None Description: The Pacific Loon has a shorter neck than the Red-throated Loon. The bill is very straight and the head is very smoothly rounded. -

09 Black-Necked Grebe

Javier Blasco -Zumeta & Gerd -Michael Heinze Sponsor is needed. Write your name here 09 Black -necked Grebe Put your logo here MOULT Complete postbreeding moult, usually finished by October. Partial postjuvenile moult, confi- ned to body and tail feathers; finished in some birds by december. Both types of age have a partial prebreeding moult changing tail and body feathers to acquire the breeding plumage. BLACK -NECKED GREBE (Podiceps PHENOLOGY nigricollis ) I II III IV V VI VII VIII IX X XI XII IDENTIFICATION 28 -34 cm. In breeding plumage with black up- perparts, head and neck; with golden feather STATUS IN ARAGON tufts on sides of head; chestnut flanks; white vent. In non breeding plumage with dark up- Residen but always an uncommon species. perparts; pale underparts; black on head only till A very scarce breeder with some wintering the eyes. birds. SIMILAR SPECIES In Aragon, this species is unmistakable. SEXING Plumage of both sexes alike, but in breeding plumage male usually with more rufous flanks and yellow crest than female . Size can be useful in extreme birds: male with wing longer than 136 mm, bill longer than 27 mm. Female with wing shorter than 127 mm, bill shorter than 21 mm. AGEING 4 types of age can be recognized: Juvenile with pale brown upperparts, often with olive hue; crown and hindneck with olive hue; sides of neck buff; scapulars usually with re- mains of down on tips, iris brown with orange tinge. 1st year winter similar to adults , but with ju- venile brown feathers on upperparts mixed with black adult -type feathers. -

Persistence and Abundance of the Western Grebe (Aechmophorus Occidentalis) in Alberta

University of Alberta Persistence and abundance of the Western Grebe (Aechmophorus occidentalis) in Alberta by Mara Elaine Erickson A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Ecology Department of Biological Sciences ©Mara Elaine Erickson Spring 2010 Edmonton, Alberta Permission is hereby granted to the University of Alberta Libraries to reproduce single copies of this thesis and to lend or sell such copies for private, scholarly or scientific research purposes only. Where the thesis is converted to, or otherwise made available in digital form, the University of Alberta will advise potential users of the thesis of these terms. The author reserves all other publication and other rights in association with the copyright in the thesis and, except as herein before provided, neither the thesis nor any substantial portion thereof may be printed or otherwise reproduced in any material form whatsoever without the author's prior written permission. Library and Archives Bibliothèque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l’édition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60605-6 Our file Notre référence ISBN: 978-0-494-60605-6 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L’auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant à la Bibliothèque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par télécommunication ou par l’Internet, prêter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des thèses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, à des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, électronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats.