How the Suffrage and Antisuffrage Movements in Illinois Transformed Themselves and the Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Party Women and the Rhetorical Foundations of Political Womanhood

“A New Woman in Old Fashioned Times”: Party Women and the Rhetorical Foundations of Political Womanhood A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Emily Ann Berg Paup IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Karlyn Kohrs Campbell, Advisor December 2012 © Emily Ann Berg Paup 2012 i Acknowledgments My favorite childhood author, Louis May Alcott, once wrote: “We all have our own life to pursue, our own kind of dream to be weaving, and we all have the power to make wishes come true, as long as we keep believing.” These words have guided me through much of my life as I have found a love of learning, a passion for teaching, and an appreciation for women who paved the way so that I might celebrate my successes. I would like to acknowledge those who have aided in my journey, helped to keep me believing, and molded me into the scholar that I am today. I need to begin by acknowledging those who led me to want to pursue a career in higher education in the first place. Dr. Bonnie Jefferson’s The Rhetorical Tradition was the first class that I walked into during my undergraduate years at Boston College. She made me fall in love with the history of U.S. public discourse and the study of rhetorical criticism. Ever since the fall of 2002, Bonnie has been a trusted colleague and friend who showed me what a passion for learning and teaching looked like. Dr. -

Woman Suffrage

Rare Book Miscellany: WOMAN SUFFRAGE On-Line Only: Catalog # 223 Second Life Books Inc. ABAA- ILAB P.O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA 01237 413-447-8010 fax: 413-499-1540 Email: [email protected] Rare Book Miscellany: WOMAN SUFFRAGE On-Line Only Catalog # 223 Terms : All books are fully guaranteed and returnable within 7 days of receipt. Massachusetts residents please add 5% sales tax. Postage is additional. Libraries will be billed to their requirements. Deferred billing available upon request. We accept MasterCard, Visa and American Express. ALL ITEMS ARE IN VERY GOOD OR BETTER CONDITION , EXCEPT AS NOTED . Orders may be made by mail, email, phone or fax to: Second Life Books, Inc. P. O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA. 01237 Phone (413) 447-8010 Fax (413) 499-1540 Email:[email protected] Search all our books at our web site: www.secondlifebooks.com Item 140 1. ALGEO, Sara M. THE STORY OF A SUB PIONEER. Providence: Snow & Farnham, (1925). First Edition. 8vo, 318 pp. Illustrated throughout with 91 half-tones. 1/1000 numbered copies. This is #90, one of the 200 reserved for the author's fellow suffragists. This is an ex-library copy with the bookplate of a MA library. Corners of front and rear blanks cropped. Krichmar 1412. [24699] $125.00 Covers the period 1908-1920: the RI suffrage bill, etc. Algeo was in the RI Woman Suffrage Party and active in the national organizing campaign. This is a first hand account of the suffrage fight by an activist. 2. ALGEO, Sara M. -

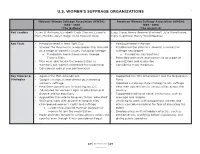

Suffrage Organizations Chart.Indd

U.S. WOMEN’S SUFFRAGE ORGANIZATIONS 1 National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA), American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), 1869 - 1890 1869 - 1890 “The National” “The American” Key Leaders Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Lucy Stone, Henry Browne Blackwell, Julia Ward Howe, Mott, Matilda Joslyn Gage, Anna Howard Shaw Mary Livermore, Henry Ward Beecher Key Facts • Headquartered in New York City • Headquartered in Boston • Started The Revolution, a newspaper that focused • Established the Woman’s Journal, a successful on a range of women’s issues, including suffrage suffrage newspaper o Funded by a pro-slavery man, George o Funded by subscriptions Francis Train • Permitted both men and women to be a part of • Men were able to join the organization as organization and leadership members but women controlled the leadership • Considered more moderate • Considered radical and controversial Key Stances & • Against the 15th Amendment • Supported the 15th Amendment and the Republican Strategies • Sought a national amendment guaranteeing Party women’s suffrage • Adopted a state-by-state strategy to win suffrage • Held their conventions in Washington, D.C • Held their conventions in various cities across the • Advocated for women’s right to education and country divorce and for equal pay • Supported traditional social institutions, such as • Argued for the vote to be given to the “educated” marriage and religion • Willing to work with anyone as long as they • Unwilling to work with polygamous women and championed women’s rights and suffrage others considered radical, for fear of alienating the o Leadership allowed Mormon polygamist public women to join the organization • Employed less militant lobbying tactics, such as • Made attempts to vote in various places across the petition drives, testifying before legislatures, and country even though it was considered illegal giving public speeches © Better Days 2020 U.S. -

The Masses Index 1911-1917

The Masses Index 1911-1917 1 Radical Magazines ofthe Twentieth Century Series THE MASSES INDEX 1911-1917 1911-1917 By Theodore F. Watts \ Forthcoming volumes in the "Radical Magazines ofthe Twentieth Century Series:" The Liberator (1918-1924) The New Masses (Monthly, 1926-1933) The New Masses (Weekly, 1934-1948) Foreword The handful ofyears leading up to America's entry into World War I was Socialism's glorious moment in America, its high-water mark ofenergy and promise. This pregnant moment in time was the result ofdecades of ferment, indeed more than 100 years of growing agitation to curb the excesses of American capitalism, beginning with Jefferson's warnings about the deleterious effects ofurbanized culture, and proceeding through the painful dislocation ofthe emerging industrial economy, the ex- cesses ofspeculation during the Civil War, the rise ofthe robber barons, the suppression oflabor unions, the exploitation of immigrant labor, through to the exposes ofthe muckrakers. By the decade ofthe ' teens, the evils ofcapitalism were widely acknowledged, even by champions ofthe system. Socialism became capitalism's logical alternative and the rallying point for the disenchanted. It was, of course, merely a vision, largely untested. But that is exactly why the socialist movement was so formidable. The artists and writers of the Masses didn't need to defend socialism when Rockefeller's henchmen were gunning down mine workers and their families in Ludlow, Colorado. Eventually, the American socialist movement would shatter on the rocks ofthe Russian revolution, when it was finally confronted with the reality ofa socialist state, but that story comes later, after the Masses was run from the stage. -

The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements

The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements By Laura K. Nelson A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kim Voss, Chair Professor Raka Ray Professor Robin Einhorn Fall 2014 Copyright 2014 by Laura K. Nelson 1 Abstract The Power of Place: Structure, Culture, and Continuities in U.S. Women's Movements by Laura K. Nelson Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology University of California, Berkeley Professor Kim Voss, Chair This dissertation challenges the widely accepted historical accounts of women's movements in the United States. Second-wave feminism, claim historians, was unique because of its development of radical feminism, defined by its insistence on changing consciousness, its focus on women being oppressed as a sex-class, and its efforts to emphasize the political nature of personal problems. I show that these features of second-wave radical feminism were not in fact unique but existed in almost identical forms during the first wave. Moreover, within each wave of feminism there were debates about the best way to fight women's oppression. As radical feminists were arguing that men as a sex-class oppress women as a sex-class, other feminists were claiming that the social system, not men, is to blame. This debate existed in both the first and second waves. Importantly, in both the first and the second wave there was a geographical dimension to these debates: women and organizations in Chicago argued that the social system was to blame while women and organizations in New York City argued that men were to blame. -

The Legacy of Woman Suffrage for the Voting Right

UCLA UCLA Women's Law Journal Title Dominance and Democracy: The Legacy of Woman Suffrage for the Voting Right Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4r4018j9 Journal UCLA Women's Law Journal, 5(1) Author Lind, JoEllen Publication Date 1994 DOI 10.5070/L351017615 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLE DOMINANCE AND DEMOCRACY: THE LEGACY OF WOMAN SUFFRAGE FOR THE VOTING RIGHT JoEllen Lind* TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................ 104 I. VOTING AND THE COMPLEX OF DOMINANCE ......... 110 A. The Nineteenth Century Gender System .......... 111 B. The Vote and the Complex of Dominance ........ 113 C. Political Theories About the Vote ................. 116 1. Two Understandings of Political Participation .................................. 120 2. Our Federalism ............................... 123 II. A SUFFRAGE HISTORY PRIMER ...................... 126 A. From Invisibility to Organization: The Women's Movement in Antebellum America ............... 128 1. Early Causes ................................. 128 2. Women and Abolition ........................ 138 3. Seneca Falls - Political Discourse at the M argin ....................................... 145 * Professor of Law, Valparaiso University; A.B. Stanford University, 1972; J.D. University of California at Los Angeles, 1975; Candidate Ph.D. (political the- ory) University of Utah, 1994. I wish to thank Akhil Amar for the careful reading he gave this piece, and in particular for his assistance with Reconstruction history. In addition, my colleagues Ivan Bodensteiner, Laura Gaston Dooley, and Rosalie Levinson provided me with perspicuous editorial advice. Special acknowledgment should also be given to Amy Hague, Curator of the Sophia Smith Collection of Smith College, for all of her help with original resources. Finally, I wish to thank my research assistants Christine Brookbank, Colleen Kritlow, and Jill Norton for their exceptional contribution to this project. -

Socialist Collections in the Tamiment Library 1872-1956

Socialist Collections in the Tamiment Library 1872-1956 , '" Pro uesf ---- Start here. ---- This volume is a fmding aid to a ProQuest Research Collection in Microform. To learn more visit: www.proquest.com or call (800) 521-0600 About ProQuest: ProQuest connects people with vetted, reliable information. Key to serious research. the company has forged a 70-year reputation as a gateway to the world's knowledge - from dissertations to governmental and cultural archives to news, in all its forms. Its role is essential to libraries and other organizations whose missions depend on the delivery of complete, trustworthy information. 789 E. E1se~howcr Paik1·1ay • P 0 Box 1346 • Ann Arbor, r.1148106-1346 • USA •Tel: 734.461 4700 • Toll-free 800-521-0600 • wvNJ.proquest.com Socialist Collections in the Tamiment Library 1872-1956 A Guide To The Microfilm Edition Edited by Thomas C. Pardo !NIYfn Microfilming Corporation of America 1.J.J.J A New York Times Company This guide accesses the 68 reels that comprise the microfilm edition of the Socialist Collections in the Tamiment Library, 1872-1956. Information on the availability of this collection and the guide may be obtained by writing: Microfilming Corporation of America 1620 Hawkins Avenue/P.O. Box 10 Sanford, North Carolina 27330 Copyright © 1979, Microfilming Corporation of America ISBN 0-667-00572-2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE v NOTE TO THE RESEARCHER . vii INTRODUCTION . • 1 BRIEF REEL LIST 3 COLLECTION I. SOCIALIST MINUTEBOOKS, 1872-1907 • 5 COLLECTION II. SOCIAL DEMOCRATIC PARTY PAPERS, 1900-1905 . • • . • . • • • . 9 COLLECTION III. SOCIALIST LABOR PARTY PAPERS, 1879-1900 13 COLLECTION IV. -

Unit 2 1870: Gender and the Reconstruction of American Democracy

Unit 2 1870: Gender and the Reconstruction of American Democracy Manisha Sinha Mellon-Schlesinger Fellow, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study ’20 James L. and Shirley A. Draper Chair in American History, University of Connecticut https://history.uconn.edu/faculty-by-name/manisha-sinha/ International Council of Women, Washington, D.C., 1888, Seneca Falls Historical Site The year 1870 marked an important turning point in the history of women’s suffrage in the United States. The decades preceding 1870 witnessed the emergence of a women’s rights movement and women’s activism within the movement to abolish slavery. Women’s activism reached its zenith during the Civil War and Reconstruction period. Most women involved in these campaigns saw their own cause as interconnected with that of enslaved and, after emancipation, freedpeople. However, with the passage of the 14th and 15th constitutional amendments that enfranchised adult Black men, women’s suffragists divided into two groups: those who retained their commitment to abolitionist feminism and those who sought to fight for women’s rights by any means necessary, including an expedient repudiation of the abolitionist commitment to racial equality. Women’s rights activists organized themselves into two competing suffrage organizations and, after 1870, continued their long battle for the vote. Many forms of subsequent women’s activism—in temperance, social reform, churches, and clubs— intersected with the suffrage movement, because prominent women in these endeavors were suffragists. African American women developed their own organizations and clubs to fight both for the franchise and against new forms of racial oppression after the end of Reconstruction. -

The Complete Syllabus

About this #SuffrageSyllabus Suffrage Pin, c. 1910s, Memorabilia Collection, Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University This syllabus, part of the Schlesinger Library’s Long 19th Amendment Project, takes students through a semester-long course of readings and assignments on the broad subject of women’s political rights in the United States. Organized around a series of turning-point moments from the creation of the independent nation in 1776 to the present day, the syllabus places American women’s still-unfinished struggle for full and equal citizenship in a broad intersectional context. The effort to build this #syllabus began with an open call on social media by the unit creators and Johns Hopkins historian Martha Jones, who has been instrumental in many parts of the Long 19th Amendment Project. Many responded to that call; Cathleen Cahill, Mary Chapman, Andrew Cohen, and Beverly Palmer contributed particular ideas that directly shaped the result. We have cast a wide net in the topics, readings, and approaches outlined in this course, which has meant making hard choices about coverage and content. We hope that individual instructors will adapt as well as adopt this syllabus, diving deeper into particular questions and creating alternative frameworks for exploration. Such an inquiry could begin almost anywhere; women in many parts of the world have fought for their emancipation since antiquity. During the early modern period, a lively print debate on “the woman question” raged in Western Europe, producing foundational texts that later women’s rights thinkers built on. From the age of revolutions forward, those advocating for the rights of women often allied with thinkers and activists seeking the abolition of slavery. -

American Studies | Subject Catalog (PDF)

American Studies Catalog of Microform (Research Collections, Serials, and Dissertations) http://www.proquest.com/en-US/catalogs/collections/rc-search.shtml [email protected] 800.521.0600 ext. 2793 or 734.761.4700 ext. 2793 USC023-03 updated May 2010 Table of Contents About This Catalog ............................................................................................... 3 The Advantages of Microform ........................................................................... 4 Research Collections............................................................................................. 5 Personal Papers .................................................................................................................................................6 Local History & Census Documents ............................................................................................................. 42 Government Documents & Political Papers ................................................................................................ 48 Timeline America ............................................................................................................................................ 65 American Revolution ................................................................................................................................................... 65 War of 1812 .................................................................................................................................................................. -

Woman Suffrage

100 years WOMAN SUFFRAGE 1920-2020 On-Line Only: Catalog # 230 Second Life Books Inc. ABAA- ILAB P.O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA 01237 413-447-8010 fax: 413-499-1540 Email: [email protected] WOMAN SUFFRAGE 1920-2020 On-Line Only Catalog # 230 Terms : All books are fully guaranteed and returnable within 7 days of receipt. Massachusetts residents please add 6.25% sales tax. Postage is additional. Libraries will be billed to their requirements. Deferred billing available upon request. We accept MasterCard, Visa and American Express. ALL ITEMS ARE IN VERY GOOD OR BETTER CONDITION , EXCEPT AS NOTED . Orders may be made by mail, email, phone or fax to: Second Life Books, Inc. P. O. Box 242, 55 Quarry Road Lanesborough, MA. 01237 Phone (413) 447-8010 Fax (413) 499-1540 Email:[email protected] Search all our books at our web site: www.secondlifebooks.com 1. ALGEO, Sara M. THE STORY OF A SUB PIONEER. Providence: Snow & Farnham, (1925). First Edition. 8vo, 318 pp. Illustrated throughout with 91 half-tones. 1/1000 numbered copies. This is #90, one of the 200 reserved for the author's fellow suffragists. This is an ex-library copy with the bookplate of a MA library. Corners of front and rear blanks cropped. Krichmar 1412. [24699] $125.00 Covers the period 1908-1920: the RI suffrage bill, etc. Algeo was in the RI Woman Suffrage Party and active in the national organizing campaign. This is a first hand account of the suffrage fight by an activist. 2. ALGEO, Sara M. -

How Women Won the Vote: Additional Print & Online Woman Suffrage

How Women Won the Vote Additional Print & Online Woman Suffrage Resources In recognition of Equality Day, and following up on the “How Women Won the Vote” Gazette, the NWHP has posted on its website an extensive new List of Resources on suffragists and the suffrage movement. The Suffrage List offers “Cookbooks, Patterns, Songs and Surprises – Leads to a Variety of Votes for Women Resources,” with items in three dozen categories. The Reference Lists cite sixty-six biographies of suffragists, many of which are recent, and more than 500 books and links that offer more information. There is material on each state’s suffrage history that adds to the information in the Gazette. [link] The National Women’s History Project’s 2017 Gazette, How Women Won the Vote, celebrates suffragists and activity in all the states and covers plans for the 2020 suffrage centennial. However, with limited space, it did not list any books or other media. So here are selected books, resources and additional links to encourage further research into individual suffragists and the multifaceted suffrage movement. The supplemental resources specifically for Suffragists Active in Every State appear at the end. Also check out resources on the web. There is a wealth of information, books and lesson plans on suffrage and women’s history now available online. These resources are divided into four sections: The Suffrage List Cookbooks, Patterns, Songs and Surprises – Leads to a Variety of Votes for Women Resources Suffrage Films, Books & Resources by Topic Biographies, Autobiographies