Hawaiian Breach Access: a Customary Right Michael D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

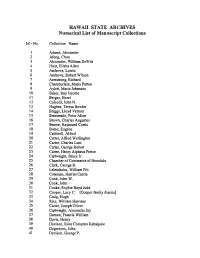

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections

HAWAII STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript Collections M-No. Collection Name 1 Adams, Alexander 2 Afong, Chun 3 Alexander, WilliamDe Witt 4 Hunt, Elisha Allen 5 Andrews, Lorrin 6 Andrews, Robert Wilson 7 Armstrong,Richard 8 Chamberlain, MariaPatton 9 Aylett, Marie Johannes 10 Baker, Ray Jerome 11 Berger, Henri 12 Colcord, John N. 13 Hughes, Teresa Bowler 14 Briggs, Lloyd Vernon 15 Brinsmade, Peter Allen 16 Brown, CharlesAugustus 17 Brown, Raymond Curtis 18 Burns, Eugene 19 Caldwell, Alfred 20 Carter, AlfredWellington 21 Carter,Charles Lunt 22 Carter, George Robert 23 Carter, Henry Alpheus Pierce 24 Cartwright, Bruce Jr. 25 Chamber of Commerce of Honolulu 26 Clark, George R. 27 Leleiohoku, William Pitt 28 Coleman, HarrietCastle 29 Cook, John W. 30 Cook, John 31 Cooke, Sophie Boyd Judd 32 Cooper, Lucy C. [Cooper family diaries] 33 Craig, Hugh 34 Rice, William Harrison 35 Carter,Joseph Oliver 36 Cartwright,Alexander Joy 37 Damon, Francis William 38 Davis, Henry 39 Davison, Rose Compton Kahaipule 40 Degreaves, John 41 Denison, George P. HAWAIi STATE ARCHIVES Numerical List of Manuscript collections M-No. Collection Name 42 Dimond, Henry 43 Dole, Sanford Ballard 44 Dutton, Joseph (Ira Barnes) 45 Emma, Queen 46 Ford, Seth Porter, M.D. 47 Frasher, Charles E. 48 Gibson, Walter Murray 49 Giffard, Walter Le Montais 50 Whitney, HenryM. 51 Goodale, William Whitmore 52 Green, Mary 53 Gulick, Charles Thomas 54 Hamblet, Nicholas 55 Harding, George 56 Hartwell,Alfred Stedman 57 Hasslocher, Eugen 58 Hatch, FrancisMarch 59 Hawaiian Chiefs 60 Coan, Titus 61 Heuck, Theodor Christopher 62 Hitchcock, Edward Griffin 63 Hoffinan, Theodore 64 Honolulu Fire Department 65 Holt, John Dominis 66 Holmes, Oliver 67 Houston, Pinao G. -

1856 1877 1881 1888 1894 1900 1918 1932 Box 1-1 JOHANN FRIEDRICH HACKFELD

M-307 JOHANNFRIEDRICH HACKFELD (1856- 1932) 1856 Bornin Germany; educated there and served in German Anny. 1877 Came to Hawaii, worked in uncle's business, H. Hackfeld & Company. 1881 Became partnerin company, alongwith Paul Isenberg andH. F. Glade. 1888 Visited in Germany; marriedJulia Berkenbusch; returnedto Hawaii. 1894 H.F. Glade leftcompany; J. F. Hackfeld and Paul Isenberg became sole ownersofH. Hackfeld& Company. 1900 Moved to Germany tolive due to Mrs. Hackfeld's health. Thereafter divided his time betweenGermany and Hawaii. After 1914, he visited Honolulu only threeor fourtimes. 1918 Assets and properties ofH. Hackfeld & Company seized by U.S. Governmentunder Alien PropertyAct. Varioussuits brought againstU. S. Governmentfor restitution. 1932 August 27, J. F. Hackfeld died, Bremen, Germany. Box 1-1 United States AttorneyGeneral Opinion No. 67, February 17, 1941. Executors ofJ. F. Hackfeld'sestate brought suit against the U. S. Governmentfor larger payment than was originallyallowed in restitution forHawaiian sugar properties expropriated in 1918 by Alien Property Act authority. This document is the opinion of Circuit Judge Swan in The U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals forthe Second Circuit, February 17, 1941. M-244 HAEHAW All (BARK) Box 1-1 Shipping articleson a whaling cruise, 1864 - 1865 Hawaiian shipping articles forBark Hae Hawaii, JohnHeppingstone, master, on a whaling cruise, December 19, 1864, until :the fall of 1865". M-305 HAIKUFRUIT AND PACKlNGCOMP ANY 1903 Haiku Fruitand Packing Company incorporated. 1904 Canneryand can making plant installed; initial pack was 1,400 cases. 1911 Bought out Pukalani Dairy and Pineapple Co (founded1907 at Pauwela) 1912 Hawaiian Pineapple Company bought controlof Haiku F & P Company 1918 Controlof Haiku F & P Company bought fromHawaiian Pineapple Company by hui of Maui men, headed by H. -

Sharks Upon the Land Seth Archer Index More Information Www

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-17456-6 — Sharks upon the Land Seth Archer Index More Information Index ABCFM (American Board of ‘anā‘anā (sorcery), 109–10, 171, 172, 220 Commissioners for Foreign Missions), Andrews, Seth, 218 148, 152, 179, 187, 196, 210, 224 animal diseases, 28, 58–60 abortion, 220 annexation by US, 231, 233–34 adoption (hānai), 141, 181, 234 Aotearoa. See New Zealand adultery, 223 Arago, Jacques, 137 afterlife, 170, 200 Armstrong, Clarissa, 210 ahulau (epidemic), 101 Armstrong, Rev. Richard, 197, 207, 209, ‘aiea, 98–99 216, 220, 227 ‘Aikanaka, 187, 211 Auna, 153, 155 aikāne (male attendants), 49–50 ‘awa (kava), 28–29, 80, 81–82, 96, 97, ‘ai kapu (eating taboo), 31, 98–99, 124, 135, 139, 186 127, 129, 139–40, 141, 142, 143 bacterial diseases, 46–47 Albert, Prince, 232 Baldwin, Dwight, 216, 221, 228 alcohol consumption, 115–16, baptism, 131–33, 139, 147, 153, 162, 121, 122, 124, 135, 180, 186, 177–78, 183, 226 189, 228–29 Bayly, William, 44 Alexander I, Tsar of Russia, 95, 124 Beale, William, 195–96 ali‘i (chiefs) Beechey, Capt. Richard, 177 aikāne attendants, 49–50 Bell, Edward, 71, 72–73, 74 consumption, 122–24 Beresford, William, 56, 81 divine kingship, 27, 35 Bible, 167, 168 fatalism, 181, 182–83 Bingham, Hiram, 149, 150, 175, 177, 195 genealogy, 23, 26 Bingham, Sybil, 155, 195 kapu system, 64, 125–26 birth defects, 52 medicine and healing, 109 birth rate, 206, 217, 225, 233 mortality rates, 221 Bishop, Rev. Artemas, 198, 206, 208 relations with Britons, 40, 64 Bishop, Elizabeth Edwards, 159 sexual politics, 87 Blaisdell, Richard Kekuni, 109 Vancouver accounts, 70, 84 Blatchley, Abraham, 196 venereal disease, 49 Blonde (ship), 176 women’s role, 211 Boelen, Capt. -

Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt6t1nb227 No online items Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers: Finding Aid Processed by Brooke M. Black. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2002 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers: mssEMR 1-1323 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Nathaniel Bright Emerson Papers Dates (inclusive): 1766-1944 Bulk dates: 1860-1915 Collection Number: mssEMR 1-1323 Creator: Emerson, Nathaniel Bright, 1839-1915. Extent: 1,887 items. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of Hawaiian physician and author Nathaniel Bright Emerson (1839-1915), including a a wide range of material such as research material for his major publications about Hawaiian myths, songs, and history, manuscripts, diaries, notebooks, correspondence, and family papers. The subjects covered in this collection are: Emerson family history; the American Civil War and army hospitals; Hawaiian ethnology and culture; the Hawaiian revolutions of 1893 and 1895; Hawaiian politics; Hawaiian history; Polynesian history; Hawaiian mele; the Hawaiian hula; leprosy and the leper colony on Molokai; and Hawaiian mythology and folklore. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. -

A Brief History of the Hawaiian People

0 A BRIEF HISTORY OP 'Ill& HAWAIIAN PEOPLE ff W. D. ALEXANDER PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE HAWAIIAN KINGDOM NEW YORK,: . CINCINNATI•:• CHICAGO AMERICAN BOOK C.OMPANY Digitized by Google ' .. HARVARD COLLEGELIBRAllY BEQUESTOF RCLANOBUr.ll,' , ,E DIXOII f,'.AY 19, 1936 0oPYBIGRT, 1891, BY AlilBIOAN BooK Co)[PA.NY. W. P. 2 1 Digit zed by Google \ PREFACE AT the request of the Board of Education, I have .fi. endeavored to write a simple and concise history of the Hawaiian people, which, it is hoped, may be useful to the teachers and higher classes in our schools. As there is, however, no book in existence that covers the whole ground, and as the earlier histories are entirely out of print, it has been deemed best to prepare not merely a school-book, but a history for the benefit of the general public. This book has been written in the intervals of a labo rious occupation, from the stand-point of a patriotic Hawaiian, for the young people of this country rather than for foreign readers. This fact will account for its local coloring, and for the prominence given to certain topics of local interest. Especial pains have been taken to supply the want of a correct account of the ancient civil polity and religion of the Hawaiian race. This history is not merely a compilation. It is based upon a careful study of the original authorities, the writer having had the use of the principal existing collections of Hawaiian manuscripts, and having examined the early archives of the government, as well as nearly all the existing materials in print. -

Table 4. Hawaiian Newspaper Sources

OCS Study BOEM 2017-022 A ‘Ikena I Kai (Seaward Viewsheds): Inventory of Terrestrial Properties for Assessment of Marine Viewsheds on the Main Eight Hawaiian Islands U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region August 18, 2017 Cover image: Viewshed among the Hawaiian Islands. (Trisha Kehaulani Watson © 2014 All rights reserved) OCS Study BOEM 2017-022 Nā ‘Ikena I Kai (Seaward Viewsheds): Inventory of Terrestrial Properties for Assessment of Marine Viewsheds on the Eight Main Hawaiian Islands Authors T. Watson K. Ho‘omanawanui R. Thurman B. Thao K. Boyne Prepared under BOEM Interagency Agreement M13PG00018 By Honua Consulting 4348 Wai‘alae Avenue #254 Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96816 U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Pacific OCS Region August 18, 2016 DISCLAIMER This study was funded, in part, by the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Environmental Studies Program, Washington, DC, through Interagency Agreement Number M13PG00018 with the US Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of National Marine Sanctuaries. This report has been technically reviewed by the ONMS and the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and has been approved for publication. The views and conclusions contained in this document are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the US Government, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation for use. REPORT AVAILABILITY To download a PDF file of this report, go to the US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Environmental Studies Program Information System website and search on OCS Study BOEM 2017-022. -

Hawaiian Historical Society

TWENTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY FOR THE YEAR 1916 WITH PAPERS READ DURING THE YEAR BEFORE THE SOCIETY HONOLULU: PARADISE OF THE PACIFIC PRESS 1917 (500) John Young, Advisor of Kamehameha I. (From "Voyage au tour du Monde", Louis de Freycinet, Paris, 1827. Historique PI. 84.) TWENTY-FIFTH ANNUAL REPORT OF THE HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY FOR THE YEAR 1916 WITH PAPERS READ DURING THE YEAR BEFORE THE SOCIETY HONOLULU: PARADISE OP THE PACIFIC PRESS 1917 (500) HAWAIIAN HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS FOR 1917. PRESIDENT HON. W. P. FREAR FIRST VICE-PRESIDENT PROF. W. A. BRYAN SECOND VICE-PRESIDENT MR. J. F. EMERSON THIRD VICE-PRESIDENT HON. F. M. HATCH TREASURER HON. B. CARTWRIGHT, JR. RECORDING SECRETARY MR. EDGAR HENRIQUES CORRESPONDING SECRETARY REV. W. D. WESTERVELT LIBRARIAN MISS E. I. ALLEN Additional Members Board of Managers. EDGAR WOOD EDWARD TOWSE J. W. WALDRON TRUSTEE LIBRARY OF HAWAII W. D. WESTERVELT STANDING COMMITTEES. Library Committee. REV. W. D. WESTERVELT, Chairman R. C. LYDECKER D. F. THRUM J. F. G. STOKES J. W. WALDRON Printing Committee. B. CARTWRIGHT, JR., Chairman H. S. HAYWARD ED TOWSE L. A. THURSTON W. D. WESTERVELT Membership Committee PROF. W. A. BRYAN, Chairman C. M. COOKE J. A. DOMINIS E. A. MOTT-SMITH G. P. WILDER Genealogical Committee ED. HENRIQUES, Chairman S. B. DOLE B. CARTWRIGHT, JR. A. F. JUDD MRS. E. P. LOW CONTENTS Minutes of the Annual Meeting.... 5-0 Librarian's Report 7-9 Treasurer's Report 10-11 Corresponding Secretary's Report 12 Keport of Genealogical Committee 13 Stories of Wailua, Kauai... -

No. 08 Mormon Pacific Historical Society

a010 now mormon pacific historical society proceedings eighth annual conference MORMON HISTORY IN THE PACIFIC march 21 1987 KAHANA VALLEY recreational CENTER KAHANA HAWAII n0jpm0f4 IPACIIFBCUDACUFUC uuustoirucaidfflistolkicail SOCUIETU ipaipirqcbidiinb0 C 22ding a EIGHTH ANNUAL conference march 21 1987 presidents message 1.1 executive council 1987881987 88 1 the voice of the waves of the sea lance D chase 2 historical highlights of kahana 0.0 jimmy kaanaana 8 sam pua haaheo 0 0 0 0 0 midgeolerMidge oleroier 11 the hui of kahana robert stauffer 13 presidents MESSAGE dear MPHS member for the special experience we all enjoyed at kahanaKahanainin 1987 we owe thanks to many people I1 especially want to recognize jimmy kaanaana and his family jimmy not only serves as a most efficient treasurer for MPHS but his and his familysfamilys efforts at kahana were little short of heroic finally special thanks go to anne pikula of IPS and anna kaanga of the religion department for their work in preparing the proceedings for us I1 hope you enjoy reading them as much as we enjoyed preparing these papers while there were fewer of them than usual the memories of the wonderful tours we had and what I1 believe the hihighh quality of those papers included will compare favorably with past proceedings president midge oler and council member lanny britsch suggested the 1988 MPHS meeting be held at and feature presentations on the hawaii temple consequently the 1988 gathering will feature a tour and lecture by president D arthur haycock pertaining to the extensive -

Kekuaokalani: an Historical Fiction Exploration of the Hawaiian Iconoclasm

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Undergraduate Honors Theses 2018-12-07 Kekuaokalani: An Historical Fiction Exploration of the Hawaiian Iconoclasm Alex Oldroyd Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub_uht Part of the English Language and Literature Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Oldroyd, Alex, "Kekuaokalani: An Historical Fiction Exploration of the Hawaiian Iconoclasm" (2018). Undergraduate Honors Theses. 54. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studentpub_uht/54 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Honors Thesis KEKUAOKALANI: AN HISTORAL FICTION EXPLORATION OF THE HAWAIIAN ICONOCLASM by Alexander Keone Kapuni Oldroyd Submitted to Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of graduation requirements for University Honors English Department Brigham Young University December 2018 Advisor: John Bennion, Honors Coordinator: John Talbot ABSTRACT KEKUAOKALANI: AN HISTORAL FICTION EXPLORATION OF THE HAWAIIAN ICONOCLASM Alexander K. K. Oldroyd English Department Bachelor of Arts This thesis offers an exploration of the Hawaiian Iconoclasm of 1819 through the lens of an historical fiction novella. The thesis consists of two parts: a critical introduction outlining the theoretical background and writing process and the novella itself. 1819 was a year of incredible change on Hawaiian Islands. Kamehameha, the Great Uniter and first monarch of the Kingdom of Hawaiʻi, had recently died, thousands of the indigenous population were dying, and foreign powers were arriving with increasing frequency, bringing with them change that could not be undone. -

Kauai Marriage Records 1845

Kauai Marriage Records 1845 - 1929 from Hawaii State Archives Name Date Book and Page Location _____(k) - Pale : 04-24-1838 , Kalina (k) - Kalaiki : 04-27-1838 , Lauli (k) - Ono : 05-01-1838 , Kalaipaka (k) - Kulepe : 05-07-1838 , Opunui (k) - Kealiikehekili : 05-07-1838 , Kaunuohua (k) - Moo : 07-04-1838 , Halau (k) - Kahauna : 07-11-1838 , Naehu (k) - Kapapa : 07-11-1838 K-8a p137 Unknown __pe (k) - Keaka : 12-30-1833 , Pahiha (k) - Nahalenui : 12-30-1833 , Kapuaiki (k) - Kepuu : 12-30-1833 , Molina (k) - Nailimala : 12-30-1833 , Maipehu (k) - Awili : 01-14-1834 , Kupehea (k) - Napalapalai : 01-14-1834 , Naluahi (k) - Naoni : 01-14-1834 K-8a p101 Unknown Aana (k) - Kahiuaia , Aaana (k) - Kahiuaia :1879-10-30 : K-15 p14 Waimea Aarona, Palupalu (k) - Kamaka, Sela :1897-06-26 : K-19 p29 Hanalei Abaca, Militan (k) - Lovell, Mary :1928-06-23 : K-26 p422 Kawaihau Abargis, Rufo (k) - Apu, Harriet :1918-05-18 : K-30 p12 Lihue Abe, Asagiro (k) - Amano, Toyono :1912-04-19 : K-28 p33 Lihue Abilliar, Branlio (k) - Riveira, Isabella Torres :1926-03-24 : K-26 p325 Kawaihau Aboabo, Antonio (k) - Gaspi, Anastacia :1925-03-02 : K-27 p215 Koloa Abreu, David (k) - Cambra, Frances :1927-11-16 : K-27 p346 Koloa Abreu, Joe G. (k) - Farias, Lucy :1922-08-25 : K-27 p68 Koloa Abreu, Jose (k) - Ludvina Gregoria :1905-01-16 : K-24 p41 Koloa Abulon, Juan (k) - Kadis, Juliana :1923-06-25 : K-22 p18 Waimea Acob, Cornillo (k) - Cadavona, Leancia :1928-12-16 : K-29 p121 Lihue Acoba, Claudio (k) - Agustin, Agapita :1924-05-17 : K-27 p151 Koloa Acosta, Balbino (k) - -

The Kumulipo Translated by Queen Liliuokalani

AN ACCOUNT OF THE CREATION OF THE WORLD ACCORDING TO HAWAIIAN TRADITION TRANSLATED FROM ORIGINAL MANUSCRIPTS PRESERVED EXCLUSIVELY IN HER MAJESTY'S FAMILY BY LILIUOKALANI OF HAWAII PRAYER OF DEDICATION THE CREATION FOR KA Ii MAMAO FROM HIM TO HIS DAUGHTER ALAPAI WAHINE LILIUOKALANI'S GREAT-GRANDMOTHER COMPOSED BY KEAULUMOKU IN 1700 AND TRANSLATED BY LILIUOKALANI DURING HER IMPRISONMENT IN 1895 AT IOLANI PALACE AND AFTERWARDS AT WASHINGTON PLACE HONOLULU WAS COMPLETED AT WASHINGTON D.C. MAY 20, 1897 LEE AND SHEPARD, BOSTON ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN 1897 The Kumulipo Translated By Queen Liliuokalani. This edition created and published by Global Grey 2014. GLOBAL GREY NOTHING BUT E-BOOKS TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION THE FIRST ERA THE SECOND ERA THE THIRD ERA THE FOURTH ERA THE FIFTH ERA THE SIXTH ERA THE SEVENTH ERA THE EIGHTH ERA THE NINTH ERA THE TENTH ERA THE ELEVENTH ERA THE TWELFTH ERA A BRANCH OF THE TWELFTH ERA THE FOURTEENTH ERA THE FIFTEENTH ERA THE SIXTEENTH ERA KALAKAUA AND LILIUOKALANI'S GENEALOGY 1 The Kumulipo Translated By Queen Liliuokalani INTRODUCTION THERE are several reasons for the publication of this work, the translation of which pleasantly employed me while imprisoned by the present rulers of Hawaii. It will be to my friends a souvenir of that part of my own life, and possibly it may also be of value to genealogists and scientific men of a few societies to which a copy will be forwarded. The folk-lore or traditions of an aboriginal people have of late years been considered of inestimable value; language itself changes, and there are terms and allusions herein to the natural history of Hawaii, which might be forgotten in future years without some such history as this to preserve them to posterity. -

1 DRAFT 5-13-15 1778 ROAD to STATEHOOD 1959 Prior to 1778 and Captain Cook the Following Is Quoted From

DRAFT 5-13-15 1778 ROAD TO STATEHOOD 1959 Prior to 1778 and Captain Cook The following is quoted from www.freehawaii.org which obtained it from <http;//www.vrmaui.com/pray4hawaii/> History 1 - The Beginning to Pa‘ao All quotes, unless otherwise noted, are taken from Daniel Kikawa's excellent book, Perpetuated in Righteousness. The language of the Polynesian peoples is basically one language, the missionary translators who first assigned a written spelling for the different island groups, heard the words differently and represented these sounds that they heard with different letters. For instance the Hawaiian word for 'woman' is wahine (vah-hee-nee), the Tongan word for 'woman' is fahine (fah-hee-nee). Much like the differences between American English and British English - there is understanding but differences in accents and idioms. So, the oral traditions of the Polynesian peoples, with minor differences, give a remarkably similar account of their history and beliefs. There are Polynesians today, who can recite their lineage back to one common ancestor. Here are some excerpts from those accounts. Note that these predate the coming of the missionaries and were not influenced by Biblical record. These legends include stories from Hawaii, Tahiti, Samoa, Tonga, Marquesa and the Maori of New Zealand. `Fornander (leading foreign source of Hawaiian history) said, ". I learned that the ancient Hawaiians at one time worshipped one god, comprised of three beings, and respectively called Kane, Ku and Lono, equal in nature, but distinctive in attributes..." This Polynesian god had many titles, but one name, too holy to be mentioned in casual conversation and this name was`Io.