The Festivities of the Light of Carnide: a Persistent Authenticity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hygiea Internationalis

Regional Dynamics and Social Diversity – Portugal in the 21st Century Teresa Ferreira Rodrigues Introduction hrough its history Portugal always presented regional differences concerning population distribution, as well as fertility and mortality trends. Local T specificities related to life and death levels reflect diverse socioeconomic conditions and also different health coverage. We will try to diagnose the main concerns and future challenges related to those regional differences, using quantitative and qualitative data on demographic trends, well-being average levels and health services offer. We want to demonstrate that this kind of academic researches can be useful to policy makers, helping them: (1) to implement regional directed policies; (2) to reduce internal diversity; and (3) to improve quality of life in the most excluded areas. Our first issue consists in measuring the link between Portuguese modernization and asymmetries on social well-being levels1. Today Portugal faces some modera- tion on population growth rates, a total dependency on migration rates, both exter- nal and internal, as well as aged structures. But national average numbers are totally different from those at a regional level, mainly if using non demographic indicators, such as average living patterns or purchase power2. The paper begins with a short diagnosis on the huge demographic and socioeco- nomic changes of the last decades. In the second part we analyze the extent of the link between those changes and regional convergence on well-being levels. Finally, we try to determine the extent of regional contrasts, their main causes and the rela- tionship between social change and local average wealth standards, as well as the main problems and challenges that will be under discussion in the years to come, in what concerns to health policies. -

FICHA GLOBAL PMUS Abril16

PLANO DE AÇÃO MOBILIDADE URBANA SUSTENTÁVEL (FICHA GLOBAL) Identificação da NUT III Área Metropolitana de Lisboa Territórios abrangidos pelas intervenções Concelho de Lisboa JUSTIFICAÇÃO PARA AS INTERVENÇÕES NOS TERRITÓRIOS IDENTIFICADOS Portugal tem definido ao longo dos últimos anos uma série de políticas e instrumentos que apontam à redução da sua elevada dependência energética dos combustíveis fósseis, dos impactos ambientais que a utilização destes incorporam e da sua inerente contribuição para as emissões de gases com efeitos de estufa e para as alterações climáticas. A cidade de Lisboa também está apostada em contribuir para os mesmos objectivos, e tem ela própria levado a cabo uma série de medidas que visam aumentar a eficiência energética do seu sistema urbano, reduzir as poluições atmosférica e sonora, e mitigar as suas responsabilidades em termos de emissões de CO2. Estas preocupações são hoje centrais em todas as estratégias e políticas definidas pela cidade, que tem assumido compromissos e lançado acções que permitam aumentar permanentemente os níveis de sustentabilidade e resiliência da cidade. Documentos como a Carta Estratégica de Lisboa 2010/2014, o PDML, o Pacto dos Autarcas subscrito por Lisboa, o Plano de Acção para a Sustentabilidade Energética de Lisboa ou o Lisboa-Europa 2020 são disso exemplos. No caso do sector dos transportes, a cidade está apostada em promover uma alteração na repartição modal que visa racionalizar a utilização do automóvel e aumentar as deslocações a pé, de bicicleta e de transportes públicos, reduzindo assim decididamente os consumos energéticos e as emissões dentro do seu perímetro territorial, humanizando a cidade e aumentando a qualidade de vida dos que nela vivem, trabalham ou estudam, bem como dos que a visitam. -

URBAN PROJECT | NÓ DO LUMIAR and the Lisbon Northwest Gateway

URBAN PROJECT | NÓ DO LUMIAR and the Lisbon Northwest Gateway Gonçalo Duarte Pita Architecture Dissertation | Instituto Superior Técnico Coordinator: Prof. Carlos Moniz de Almeida Azenha Pereira da Cruz ABSTRACT The following report presents the work carried out for 2010/2012 Final Project course. The conducting element of this report is the impact road infrastructures may have, particularly when inserted in the urban context, whether they are generators of that context or the main cause of its frag- mentation. The mono-functionality of the road layout, which is a consequence of a mono-disciplinary approach to its conception, led to the incapacity of the structural road system to be part of the contem- porary city as an integrated actor of the urban space and therefore becoming an intrusive element. Supported by a reflection on road infrastructures, the goal of this report is to analyze the Lisbon struc- tural route consisting of Calçada de Carriche and Av. Padre Cruz. — the Northwest Gateway —, and the conception of a project on Nó do Lumiar, its main articulation point. Being one of Lisbon’s main gateways for centuries, the Northwest Gateway was responsible for defining the mobility structure of the North Ring when it was still part of the city’s periphery. Today, due to redefinitions of its route and section, it is an element of urban discontinuity along with other high performance roads as Eixo N-S and 2ª Circular. Nó do Lumiar is at this moment a dysfunctional urban centre due to the powerfull impact of its road system. Despite allowing an effective accessibility to automobiles on a broader range of the territory, its impact does not allow for a comfortable use of the space where it’s inserted, a space made up of elements of undeniable historic, patrimonial, cultural and administrative value. -

Rota Histórica Das Linhas De Torres G UIA Ficha Técnica

Rota Histórica das Linhas de Torres G UIA ficha técnica COORDENAÇÃO DESIGN Carlos Silveira www.tvmdesigners.pt Carlos Guardado da Silva EDIÇÃO Ana Catarina Sousa PILT – Plataforma Intermunicipal Graça Soares Nunes para as Linhas de Torres TEXTOS Ana Catarina Sousa [ACS] IMPRESSÃO Gráfica Maiadouro Ana Correia [AC] TIRAGEM 6000 exemplares Carlos Guardado da Silva [CGS] DEPÓSITO LEGAL 338 329/12 Carlos Silveira [CS] 1ª EDIÇÃO – NOVEMBRO 2011 Florbela Estêvão [FE] Paula Ferreira [PF] CATALOGAÇÃO Sandra Oliveira [SO] Rota Histórica das Linhas de Torres : Guia / coord. REVISÃO Carlos Silveira, Carlos Guardado da Silva, Ana Catarina Equipa da UT5 – Publicações Sousa, Graça Soares Nunes; [textos de] Ana Catarina Francisco de Sousa Lobo Sousa, Ana Correia, Carlos Guardado da Silva, Carlos Silveira, Florbela Estêvão, Paula Ferreira, EQUIPA DA UNIDADE TÉCNICA 5 – PUBLICAÇÕES Sandra Oliveira. – Vila Franca de Xira : PILT, 2011. Graça Soares Nunes – 120 p. : il. ; 20 cm Ana Catarina Sousa ISBN 978-989-8398-14-7 Ana Correia Carlos Guardado da Silva Carlos Silveira CDU Florbela Estêvão 355.48 Linhas de Torres Vedras (036) Isabel Silva 94(469.411)“1809/1811” (036) Joaquim Jorge 94(4)“1807/1814” (036) Natália Calvo Paula Ferreira Rui Brás Sandra Oliveira SIGLAS Susana Gonçalves CMAV Câmara Municipal de Arruda dos Vinhos CML Câmara Municipal de Loures CRÉDITOS FOTOGRÁFICOS CMM Câmara Municipal de Mafra António Pedro Vicente CMSMA Câmara Municipal de Sobral de Monte Agraço Biblioteca Nacional de Portugal CMTV Câmara Municipal de Torres Vedras Câmara Municipal -

Relatorio E Contas 2016

CAIXA DE CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA MÚTUO DE LOURES, SINTRA E LITORAL, CRL | Relatório e Contas 2016 2 Índice 00 CAIXA DE CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA MÚTUO DE LOURES, SINTRA E LITORAL, CRL | Relatório e Contas 2016 3 CAIXA DE CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA MÚTUO DE LOURES, SINTRA E LITORAL, CRL | Relatório e Contas 2016 4 0. ÍNDICE 3 1. ENQUADRAMENTO ECONÓMICO 7 1.1. Economia Mundial 9 1.2. Economia Portuguesa 13 1.3. Mercado Bancário 17 1.3.1. Evolução do Mercado Nacional de Depósitos 17 1.3.2. Evolução do Mercado Nacional de Crédito 18 1.4. Mercados Financeiros 21 1.5. Principais Riscos e Incertezas para 2017 25 2. GRUPO CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA 27 2.1. Análise Financeira do Negócio Bancário do Grupo CA 29 2.2. Outros Factos Relevantes 37 3. A REALIDADE DA CAIXA DE CRÉDITO AGRÍCOLA MÚTUO DE LOURES, SINTRA E LITORAL, C.R.L. 41 3.1. Aspetos Mais Relevantes 45 3.2. Apresentação da CCAM 47 3.2.1. Estrutura de capital 47 3.2.2. Marcos históricos 47 3.2.3. Rede de distribuição 49 3.2.4. Recursos humanos 51 4. ESTRATÉGIA E ÁREA DE NEGÓCIO 53 4.1 Objetivos Estratégicos 55 4.2 Resultados 57 4.2.1. Resultados 57 4.2.2. Margem financeira 59 4.2.3. Produto bancário 60 4.2.4. Custos operacionais 61 4.2.5. Resultado operacional 62 4.2.6. Resultado antes de imposto 62 4.2.7. Resultado líquido 62 4.3. Balanço 64 4.3.1. Crédito concedido 69 4.3.2. Crédito vencido 70 4.3.3. -

Diapositivo 1

Os Governos Urbanos de Proximidade A experiência de Lisboa O processo de reforma político-administrativa e os novos modelos de governação urbana Barcelona, 22 Octobre 2018 João Seixas CICS-NOVA / FCSH Universidade Nova de Lisboa Câmara Municipal de Lisboa / GAMRAL Os governos urbanos de proximidade e a experiência de Lisboa 1. AS RAZÕES 2. A SUBSTÂNCIA 3. O PROCESSO 4. O ACOMPANHAMENTO 5. A CAPACITAÇÃO 6. O FUTURO Área Metropolitana de Lisboa 18 municípios, com c 2.95 milhões habs. (2017) Município Central de Lisboa com c. 600 mil habs. (2017) mas com c. 1.15 milhões territoriantes / dia e 58% PIB regional Lisboa: Grandes Elementos de Re-Gravitas Uma Nova Cidade: O fim do modernismo, a crise e a transição digital. O triplo crash e o capitalismo tecno-financeiro. Novas pressões e novas oportunidades. Sustentabilidade, Coesão/Justiça espacial, Qualidade Vida. Novas políticas e estratégias anti-crise: Carta Estratégica de Lisboa, Reestruturação política e administrativa (dos bairros à metrópole), Novo plano urbanístico, planos de bairros, processos de participação (ALocal 21, Orçamento Participativo, Urbanismo Participativo), economia local e empreendedorismo urbano Uma nova Urbanidade: Novas consciências e exigências cívicas. Crescente reconhecimento sociocultural dos desfasamentos entre cidade, ecologia urbana e política. O Compromisso Político: Pressões e exigências sobre as estruturas de administração da cidade (82% inquiridos). Claro compromisso político desde 2009/10. A crescente complexidade e interconectividade da vida urbana -

Info Julho Agosto 19 EN

FCGM - Soc. de Med. Imob., S.A. | AMI 5086 Realtors - Med. Imob., Lda. | AMI 5070 ŽůůĞĐƟŽŶŚŝĂĚŽͬ>ƵŵŝĂƌͬĂƉŝƚĂůͬDŝƌĂŇŽƌĞƐͬŽƵŶƚƌLJƐŝĚĞͬDĂƐƚĞƌDŝŶĂƐ'ĞƌĂŝƐ͕ƌĂƐŝů infosiimgroup www . siimgroup . pt JULY/AUGUST2019 RESIDENTIALREPORT infosiimgroup Market in a consolidation period The market is in a period of consolidation, with the foward indicators looking like the PHMS (Portuguese House Market Survey), which measure the opinion of a panel of professionals in the market, confirming a slowdown in the number and value of transactions together with the lowest expectation for the next 12 months since the upturn in the cycle in 2013. Until the end of the year we will still be seeing the publication of very positive figures but which for the most part, in the case of used premises, relate to deals concluded in 2018 and, in the case of new buildings purchased “off-plan”, to deals concluded in some case more than 18 months ago. It is the case of the results published by the INE (National Statistics Institute of Portugal) or the base of Confidencial Imobiliário SIR (Residential Information System) which relate to the information of the Inland Revenue or pre-emption rights of the CML (Lisbon City Hall), when the deed is signed. On the other hand the database of the SIR-RU (Residential-Urban Renewal Information System) relates to sales at the time of closure of the deal and so, if there is an inflection in the market, it will be in this one where it will be felt soonest. Having made this caveat for interpreting the results, we would nevertheless emphasise that the statistics on local prices recently disclosed by the INE (25 July) allow the following conclusions to be drawn: In the period of 12 months ending on 31 March 2019, all Portuguese cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants (those covered in this study) presented positive change in the median for €/m2 compared with the previous period (31.3.2017 to 31.3.2018). -

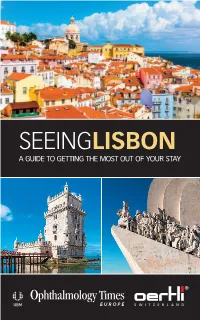

Seeinglisbon a Guide to Getting the Most out of Your Stay

SEEINGLISBON A GUIDE TO GETTING THE MOST OUT OF YOUR STAY magentablackcyanyellow ES959734_OTECG0817_cv1.pgs 08.22.2017 19:44 ADV It‘s Better, It‘s Different – Welcome to the city of discoverers Vasco da Gama began his ingenious discovery tours in the city on the western edge of Europe and greatly enhanced people’s conception of the world. He strongly questioned some approaches to knowledge and paved the way for trade with India. Following his achievements, Lisbon enjoyed a time of great prosperity that came to a sudden end following the disastrous earthquake in 1755. What we experience as an impressive city image today, especially the Baixa, was created in the 18th century. Only the Torre de Belém still reminds us of the time of great sailors and their untiring spirit of discovery. Of course, the time of individual explorations is long past, but the urge for new knowledge has remained unchanged. Today, it is a great number of people who work on the front lines with curiosity, diligence and persistence to bring about progress. They have come to Lisbon as well, to make new discoveries by sharing scientific and practical approaches. Not only in lectures, workshops and discussions but also in dialogues with industry, at the Oertli booth for example. Discover the total range of cataract and posterior segment surgical platforms, the latest functions of the OS4 device, an amazingly simple MIGS method and the new FEELceps line, or simply discover the friendliness and competence of our employees at booth no P263. We warmly welcome you! magentablackcyanyellow -

English Version

Visit LOURES So much to → →> SANTO ANTÓNIO DOS CAVALEIROS | Chapel of the Holy Spirit. Quinta do Conventinho SANTO ANTÃO DO TOJAL | Aqueduct [PIM] LOURES | Church of Santa Maria de Loures [NM] SANTO ANTÃO DO TOJAL | The Monumental Square [PIM] HERE IS heritage! LOUSA | Altar of the Church of São Pedro [BPI] We enrich and recovered memories, traditions, values and spaces that the culture and our ancestors bequeathed us. SANTA IRIA DE AZÓIA | One of the oldest olive trees in Portugal Home ← → →> SACAVÉM | Sacavém Ceramic Museum SANTO ANTÓNIO DOS CAVALEIROS | Municipal Museum of Loures HERE IS culture! BUCELAS | Museum of Vine and Wine The museum and galleries of Loures make us complicit in centuries of history that, collectively, continue to give meaning and to strengthen the identity of this territory. LOURES | Municipal Gallery Vieira da Silva Promote the heritage is to reinforce, with affection, the most identity of all: people and their ways of life. SANTA IRIA DE AZÓIA | Castle of Pirescouxe Home ← → →> URBAN ART | Terraços da Ponte, Sacavém HERE IS diversity! FOLKLORE | Ethnographic group Synonyms of culture and social identity, multiculturalism, handicraft and folklore transmit the traditions and customs of saloia’s region and all those who chose to live in. HANDICRAFT | Work done in clay BUCELAS | Feast of the wine and the grape harvest MUSIC | Meeting of Philharmonic Bands and Small Orchestras of Loures InícioHome ← → →> TRADITIONAL CUISINE | Pataniscas of cod CHEESE FACTORY | Saloios cheeses ARINTO’S CASTE | Grapes for the production of the white wines [QWPDR] VINEYARDS | Demarcated Wine Region of Bucelas HERE ARE flavours! TRADITIONAL CUISINE | Sweet scones Taste the delicacies, as well as the typical and refined products from this region, WINE TOURISM | Bucelas’ Wine is to rediscover our WINE TOURISM | Carrafouchas’ Vineyard roots, where features the wines and cheeses. -

Infosiimgroup FEV21 EN

infosiimgroup www.siimgroup.pt Monthly Report | Real Estate Market | February 2021 Lisboa | Linha de Cascais | Ribatejo | Master Minas Gerais, Brasil Sale of houses in 2020 fell by around 8%, Lisbon most affected $OWKRXJK WKH 1DWLRQDO 6WDWLVWLFDO ,QVWLWXWHV ,1( ´QDO UHSRUW LQ UHODWLRQ WR WKH VDOHV RI GZHOOLQJV LQ LV H[SHFWHG RQO\ RQ 0DUFKWKHIRUHFDVWVFXUUHQWO\SRLQWWRDIDOORIEHWZHHQDQG UHODWLYHWRWKHDOPRVWUHVLGHQWLDOSURSHUWLHVVROGLQ,W VKRXOG EH QRWHG WKDW LQ WKH WK TXDUWHU ZDV DEVROXWHO\ H[FHSWLRQDOZLWKDTXDUWHUO\PD[LPXPRISURSHUWLHVVROG ZHOODERYHWKHTXDUWHUO\DYHUDJHRIUHFHQW\HDUV DQG VRWKLVIDOORQO\UHµHFWVDQGTXDUWHUWKDWZDVKLJKO\FRQGLWLRQHG 20% E\WKHSDQGHPLF IDOORIVDOHVLQ 0RUHDFFHQWXDWHGYDULDWLRQVDUHH[SHFWHGIRU/LVERQDQG3RUWRDW /LVERQ WKLV WLPH ZLWK D GURS LQ VDOHV LQ /LVERQ RI FORVH WR D OLNHO\ HIIHFWRIWKHOLPLWHGSUHVHQFHRIIRUHLJQEX\HUV INE report - 3rd quarter of 2020 values published on 2/2/2021 PT = 9,4% 23 ,QWKHUGTXDUWHURI Almada Porto /LVERQ ZDV 18 Guimarães V. N. de Gaia WKH RQO\ RQH RI WKH Setúbal Seixal Sta. Mª da Feira Sintra Maia Gondomar PXQLFLSDOLWLHV Loures V. F. de Xira 13 Funchal V. N. de Famalicão ZLWKPRUHWKDQ Leiria Coimbra WKRXVDQG PT= 7,6% 8 Odivelas Oeiras LQKDELWDQWV ZLWK D Matosinhos Amadora accommodation, 3Q 2020 (%) Braga \HDURQ\HDU 3 Cascais FRQWUDFWLRQ RI Barcelos Lisboa KRXVHSULFHV -2 0 5 10 15 20 Rate of year-on-year variation the median sales value per m² family Rate of year-on-year variation of the median sales value per m² of family accommodation, 2Q 2020 (%) Municipalities with more than 100 thousand inhabitants: Lisbon Metropolitan Area Porto Metropolitan Area Other municipalities - 1 - Infosiimgroup | February 2021 Median value and rate of year-on-year variation of the median sales value per m², Lisbon and parishes, 3Q 2020 25 6L[ RI WKH SDULVKHV RI LISBOA = 3 375 € / m² /LVERQ VDZ D \HDURQ\HDU 20 FRQWUDFWLRQ LQ WKHLU KRXVH 15 SULFHV $MXGD &DPSR GH 2XULTXH 6mR 9LFHQWH 10 Arroios Sta. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

http://www.diva-portal.org This is the published version of a paper published in European Journal of Public Health. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Briones-Vozmediano, E., Stjärnfeldt, J., Larson, F., Nielsen, A., Eriksson, M. et al. (2020) Young men's discourses of health service utilization for Chlamydia infection testing in Stockholm European Journal of Public Health, 30(Issue Supplement_5): ckaa166.854 https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckaa166.854 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:umu:diva-179521 16th World Congress on Public Health 2020 2020–01 v847 reported genital cancers as complication to STD, 32.7% Young men’s discourses of health service utilization infertility. Some minorities (2.7%) thought that STD could for Chlamydia infection testing in Stockholm be complicated by blindness. Erica Briones-Vozmediano Conclusions: 1,2 2 2 2 Despite the high prevalence of STD among young adults, most E Briones-Vozmediano , J Stja¨ rnfeldt , F Larson , A Nielsen , M Eriksson3, M Salazar2 students knew very little about those infections. Implementing 1Department of Nursing and Physiotherapy, University of Lleida, Lleida, sexual educational programs and measuring their effectiveness Spain should be a priority. 2Department of Global Public Health, Karolinska Institut, Stockholm, Key messages: Sweden 3Department of Social Work, University of Umea˚ , Umea˚ , Sweden There is a huge lack of knowledge about sexually Contact: [email protected] Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/eurpub/article/30/Supplement_5/ckaa166.854/5915222 by Umea universitet user on 03 February 2021 Transmitted diseases among Tunisian college students. -

Real Estate Market | April & May 2021

infosiimgroup www.siimgroup.pt Monthly Report | Real Estate Market | April & May 2021 Lisboa | Linha de Cascais | Ribatejo | Master Minas Gerais, Brasil Confidence index turns positive again! Portuguese Housing Market - Confidencial Imobiliário After a year of the pandemic, the expectations of property developers and intermediaries regarding the evolution of the sales and prices in the residential market were positive again, shows the Portuguese Housing Market Survey (PHMS) for March. CONFIDENCE INDEX The Real Estate Market in the 1st quarter of 2021 2nd Q2020 1st Q2021 - 1 - Infosiimgroup | April & May 2021 $OVRDWWKHHQGRI$SULO&RQ´GHQFLDO,PRELOLiULRV:HELQDURQWKH 1st quarter of 2021 led to some surprising conclusions: • Housing sales in Portugal grew 57% between the two FRQ´QHPHQWV QGTXDUWHURIDQGVWTXDUWHU • The Lisbon Metropolitan Area maintained dynamic growth in +57% prices. Cascais and Loures were the exceptions, but with Housing sales in Portugal negligible negative variations. Lisbon saw almost no price GREW between the two FRQ´QHPHQWV variation • Despite the fall in the number of transactions in Lisbon and, within this, the strong fall in sales in new developments (-35%) this variation did not have any effect on prices. In fact, and despite the diversity of situations per segment, there was even an increase in the higher percentiles and in new construction, developers were able to adjust prices upwards as construction Purchases by progressed. foreigners fell • Purchases by foreigners were surprising and fell less than less than in average reinforcing its share in the Lisbon Urban Renewal Area other markets (from 27% to 30%) House price statistics at local level 4th quarter of 2020 (INE) After the National Statistics Institute (INE) surprised the market with the disclosure that total sales in 2020 were higher than expected by the agents in the market (see INFOSIIMGROUP March) the publication in May of “House price statistics at local level: 4th quarter of 2020” (Study for cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants) gives us a more detailed reading.