Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sintflut Textübersicht

Die Sintfluterzählung (Gen 6,5-9,17) – Eine Komposition aus zwei unterschiedlichen Erzählsträngen (Quellen?) Die Sintfluterzählung ist ein Lehrbeispiel dafür, dass die Unterscheidung in unterschiedliche Erzählstränge (Quellen) eine sinnvolle Hypothese zum Verständnis biblischer Texte ist. Auch im Text der Lutherbibel lässt sich mühelos erkennen, dass dem jetzigen Text der Sintfluterzählung zwei unterschiedliche Variationen desselben Erzählstoffes zugrunde liegen. Erkennbar sind sie sowohl an Widersprüchen im Erzählablauf als auch in Doppelungen einzelner Züge der Erzählung. (Vgl. Skript: Grundkurs AT, Kap. 5). 1. Ursache der Flut 6,5: Bosheit aller Menschen 6,11f. Verderbnis der Erde und allen Fleisches 2. Tiere in der Arche 7,2: Sieben reine und zwei unreine 6,19f: je zwei von allem Tiere bzw. Tierpaare Lebendigen 3. Dauer der Flut 7,4.12: vierzig Tage und vierzig 7,6; 8,13 = 7,11; 8,14: genau ein Nächte Jahr 4. Art der Flut 7,6; 8,2f. Sturzregen, nach dessen 7,11; 8,1f: Hervorbrechen der Aufhören das Wasser verläuft Urflut von unten und von oben 5. Herausgehen aus der Arche 8,6 12: nach Noahs 8,15 17: aufgrund der „Vogelexperiment“ Aufforderung Gottes Nahezu alle wichtigen Etappen des Geschehens werden zweimal erzählt, wobei die konkreten Vorstellungen jeweils variieren. Die nachstehende Tabelle sammelt die wichtigsten vierzehn Doppelungen und ordnet sie in zwei sinnvolle Geschehensfolgen: 1. Bosheit der Menschen 6,5 6,11-12 2. Entschluss zur Vernichtung 6,7 6,13 3. Ankündigung der Flut 7,4 6,17 4. Befehl zum Besteigen der Arche 7,1 6,18 5. Aufforderung zur Mitnahme einer bestimmten Zahl von Tieren 7,2 6,19-20 6. -

Noah Und Die Sintflut Eine Klanggeschichte an Der Orgel Für Kinder Ab 5 Jahren Von Susanna Und Uwe Maibaum

Noah und die Sintflut Eine Klanggeschichte an der Orgel für Kinder ab 5 Jahren von Susanna und Uwe Maibaum Die Musik soll improvisiert werden, in Anlehnung an die notierten Notizen oder auch ganz anders. Zu Beginn kann das Regenbogenlied einstudiert und gesungen werden, eventuell auch nur der Refrain. Lied „Leuchte, leuchte bunter Regenbogen“ (evt. nur den Refrain singen) Sprecher: In der Bibel wird von einer Zeit erzählt, in der die Menschen böse und gemein waren. Sie belogen einander, sie nahmen sich gegenseitig Dinge weg, machten Sachen kaputt und es war ihnen ganz egal, ob sie einem anderen Menschen oder einem Tier weh taten. Da bereute es Gott, dass er den Menschen geschaffen hatte und sprach: „Ich will die Menschen, die ich selber gemacht habe, so nicht haben. Ich habe keine Freude an ihnen. Alles Leben auf der Erde soll wieder aufhören.“ Orgel: düstere Klänge, unheimlich …. Sprecher: Nur ein Mann fand Gnade in seinen Augen und das war Noah, der zusammen mit seiner Frau und seinen drei Söhnen Sem, Ham und Jafet in der Zeit der Geschichte lebte. Er war fromm und Gott gehorsam. Er betete und lebte so, wie es Gott gefiel. Deswegen sagte Gott eines Tages zu ihm: „Noah, ich sehe, die Menschen sind nicht so geworden, wie ich es wollte. Ich werde allem Leben auf der Erde wieder ein Ende setzen, damit das Böse aufhört. Nur dich und deine Familie will ich vor dem Untergang bewahren. Baue eine großes Schiff, baue eine Arche! In der sollt ihr überleben und mit euch von jeder Art der Tiere ein Paar!“ Und Noah begann, zusammen mit seinen Söhnen, die Arche zu bauen. -

Theology of Judgment in Genesis 6-9

Andrews University Digital Commons @ Andrews University Dissertations Graduate Research 2005 Theology of Judgment in Genesis 6-9 Chun Sik Park Andrews University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Park, Chun Sik, "Theology of Judgment in Genesis 6-9" (2005). Dissertations. 121. https://digitalcommons.andrews.edu/dissertations/121 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Research at Digital Commons @ Andrews University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Andrews University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your interest in the Andrews University Digital Library of Dissertations and Theses. Please honor the copyright of this document by not duplicating or distributing additional copies in any form without the author’s express written permission. Thanks for your cooperation. Andrews University Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary THEOLOGY OF JUDGMENT IN GENESIS 6-9 A Disseration Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy by Chun Sik Park July 2005 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 3182013 Copyright 2005 by Park, Chun Sik All rights reserved. INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

The Influence of Ancient Esoteric Thought Through

THROUGH THE LENS OF FREEMASONRY: THE INFLUENCE OF ANCIENT ESOTERIC THOUGHT ON BEETHOVEN’S LATE WORKS BY BRIAN S. GAONA DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Music with a concentration in Performance and Literature in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2010 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Clinical Assistant Professor/Artist in Residence Brandon Vamos, Chair Professor William Kinderman, Director of Research Associate Professor Donna A. Buchanan Associate Professor Zack D. Browning ii ABSTRACT Scholarship on Ludwig van Beethoven has long addressed the composer’s affiliations with Freemasonry and other secret societies in an attempt to shed new light on his biography and works. Though Beethoven’s official membership remains unconfirmed, an examination of current scholarship and primary sources indicates a more ubiquitous Masonic presence in the composer’s life than is usually acknowledged. Whereas Mozart’s and Haydn’s Masonic status is well-known, Beethoven came of age at the historical moment when such secret societies began to be suppressed by the Habsburgs, and his Masonic associations are therefore much less transparent. Nevertheless, these connections surface through evidence such as letters, marginal notes, his Tagebuch, conversation books, books discovered in his personal library, and personal accounts from various acquaintances. This element in Beethoven’s life comes into greater relief when considered in its historical context. The “new path” in his art, as Beethoven himself called it, was bound up not only with his crisis over his incurable deafness, but with a dramatic shift in the development of social attitudes toward art and the artist. -

Biblical Creatures: the Animal As an Object of Interpretation in Pre-Modern Christian and Jewish Hermeneutic Traditions – an Introduction 7–15

vol 5 · 2018 Biblical Creatures The Animal as an Object of Interpretation in Pre-Modern Christian and Jewish Hermeneutic Traditions Karel Appel, Femmes, enfants, animaux, 1951: oil on jute, 170 x 280 cm © Cobra Museum voor Moderne Kunst Amstelveen – by SIAE 2018 Published by vol 5 · 2018 Università degli studi di Milano, Dipartimento di Studi letterari, filologici e linguistici: riviste.unimi.it/interfaces/ Edited by Paolo Borsa Christian Høgel Lars Boje Mortensen Elizabeth Tyler Initiated by Centre for Medieval Literature (SDU & York) with a grant from the The Danish National Research Foundation università degli studi di milano, dipartimento di studi letterari, filologici e linguistici centre for medieval literature Contents Astrid Lembke Biblical Creatures: The Animal as an Object of Interpretation in Pre-Modern Christian and Jewish Hermeneutic Traditions – an Introduction 7–15 Beatrice Trînca The Bride and the Wounds − “columba mea in foraminibus petrae” (Ct. 2.14) 16–30 Elke Koch A Staggering Vision: The Mediating Animal in the Textual Tradition of S. Eustachius 31–48 Julia Weitbrecht “Thou hast heard me from the horns of the unicorns:” The Biblical Unicorn in Late Medieval Religious Interpretation 49–64 David Rotman Textual Animals Turned into Narrative Fantasies: The Imaginative Middle Ages 65–77 Johannes Traulsen The Desert Fathers’ Beasts: Crocodiles in Medieval German Monastic Literature 78–89 Oren Roman A Man Fighting a Lion: A Christian ‘Theme’ in Yiddish Epics 90–110 Andreas Kraß The Hyena’s Cave:Jeremiah 12.9 in Premodern Bestiaries 111–128 Sara Offenberg Animal Attraction: Hidden Polemics in Biblical Animal Illuminations of the Michael Mahzor 129–153 Bernd Roling Zurück ins Paradies. -

Benjamin Brittens Werke Für Kinder Unter Der Besonderen Betrachtung Von Noye’S Fludde“

DIPLOMARBEIT Titel der Diplomarbeit „Benjamin Brittens Werke für Kinder unter der besonderen Betrachtung von Noye’s Fludde“ Verfasserin Elisabeth Bauer angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag.phil.) Wien, 2013 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 316 Studienrichtung lt. Studienblatt: Musikwissenschaft Betreuer: Univ.-Prof. Dr. Michele Calella Danksagung Mein aufrichtiger Dank für Ihre Unterstützung und Geduld gilt meinen Eltern Maria und Rudolf Bauer und ebenso meiner Schwester Cornelia Bauer und Alexander Rigler. Bei dieser Gelegenheit möchte ich mich ganz herzlich bei meinem Freund Rainer Hauptmann bedanken, dessen Glaube an meine Fähigkeiten mir den nötigen Rückhalt gab. Außerdem möchte ich mich ganz herzlich bei meinen langjährigen Freundinnen Daniela Karobath, Elisabeth Maier und ganz besonders bei Doris Weberberger bedanken. Ihr unermüdlicher Zuspruch und ihre Geduld bei scheinbar unüberwindbaren Problemen gaben mir die nötige Kraft um ans Ziel zu kommen. 1 Inhaltsverzeichnis 1. Einleitung ........................................................................................................................ 3 2. Gattungsbegriff Kinderoper ............................................................................................ 7 2.1 Begriffserklärung .................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Historische Entwicklung ......................................................................................... 9 2.2.1 Reformatorisch-humanistisches -

The Lights of the Church and the Light of Science

The Lights of the Church and the Light of Science Thomas Henry Huxley Project Gutenberg The Lights of the Church and the Light of Science #9 in our series by Thomas Henry Huxley This is Essay #6 from "Science and Hebrew Tradition" Copyright laws are changing all over the world, be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before posting these files!! Please take a look at the important information in this header. We encourage you to keep this file on your own disk, keeping an electronic path open for the next readers. Do not remove this. *It must legally be the first thing seen when opening the book.* In fact, our legal advisors said we can't even change margins. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **Etexts Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *These Etexts Prepared By Hundreds of Volunteers and Donations* Information on contacting Project Gutenberg to get Etexts, and further information is included below. We need your donations. Title: The Lights of the Church and the Light of Science Title: This is Essay #6 from "Science and Hebrew Tradition" Author: Thomas Henry Huxley May, 2001 [Etext #2632] Project Gutenberg The Lights of the Church and the Light of Science *******This file should be named 6saht10.txt or 6saht10.zip******** Corrected EDITIONS of our etexts get a new NUMBER, 6saht11.txt VERSIONS based on separate sources get new LETTER, 6saht10a.txt Processed by D.R. Thompson <[email protected]> Project Gutenberg Etexts are usually created from multiple editions, all of which are in the Public Domain in the United States, unless a copyright notice is included. -

A Literary Analysis of the Flood Story As a Semitic Type-Scene

Studia Antiqua Volume 13 Number 1 Article 1 May 2014 A Literary Analysis of the Flood Story as a Semitic Type-Scene Jared Pfost Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Classics Commons, History Commons, and the Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Pfost, Jared. "A Literary Analysis of the Flood Story as a Semitic Type-Scene." Studia Antiqua 13, no. 1 (2014). https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/studiaantiqua/vol13/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studia Antiqua by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. A LITERARY ANALYSIS OF THE FLOOD STORY AS A SEMITIC TYPE-SCENE JARED PFOST Jared Pfost is a student at Brigham Young University studying ancient Near Eastern studies who will begin a PhD program at Brandeis this fall. Tis essay won frst place in the annual ancient Near Eastern studies essay contest. esopotamian texts provide more direct comparative evidence for the MHebrew food story in Gen 6–9 than they do for any other part of the Hebrew canon. Te similarities and diferences have been analyzed exten- sively ever since the discovery of the Mesopotamian texts in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Te question of the historicity of the biblical food and its relationship to its Mesopotamian forerunners is ofen at the heart of the discussion: is the biblical version a historical report or simply a rework- ing of earlier deluge accounts?1 In this paper I will compare the food stories 1. -

Willy Burkhard (1900 - 1955)

Evangelische Singgemeinde Berner Kantorei und Zürcher Kantorei zu Predigern Titelbild: Links: Heinrich Schütz (1585 - 1672) Rechts: Willy Burkhard (1900 - 1955) PREDIGERKIRCHE ZÜRICH Sonntag, 30. August 2015, 19.30 Uhr Werkeinführung: 18.45 Uhr BERNER MÜNSTER Dienstag, 1. September 2015, 20.00 Uhr Werkeinführung 19.15 Uhr Abendmusik Heinrich Schütz Dietrich Buxtehude Willy Burkhard Christian Döhring – Orgel Berner Kantorei Zürcher Kantorei zu Predigern Johannes Günther – Leitung Gewidmet dem Andenken an Simon Burkhard-Wittwer (27. April 1930 - 5. August 2015) Musiker und Sohn Willy Burkhards Programm Heinrich Schütz Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes (SWV 386) Wie lieblich sind deine Wohnungen (SWV 29) Dietrich Buxtehude Passacaglia in d (BuxWV 161) Heinrich Schütz Singet dem Herrn ein neues Lied (SWV 35) Willy Burkhard Sonatine op. 52 Die Sintflut op. 97 Heinrich Schütz (1585 - 1672) Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes (SWV 386) Die Himmel erzählen die Ehre Gottes, und die Feste verkündiget seiner Hände Werk. Ein Tag sagt's dem andern, und eine Nacht tut's kund der andern. Es ist keine Sprache noch Rede, da man nicht ihre Stimme höre. Und ihre Schnur gehet aus in alle Lande, und ihre Rede an der Welt Ende. Er hat der Sonnen eine Hütten in derselben gemacht; und dieselbige gehet heraus wie ein Bräutigam aus seiner Kammer und freuet sich wie ein Held zu laufen den Weg. Sie gehet auf an einem Ende des Himmels und läuft um bis wieder an das selbige Ende, und bleibt nichts vor ihrer Hitz' verborgen. Ehre sei dem Vater, und dem Sohn und auch dem Heil'gen Geiste, wie es war im Anfang, jetzt und immerdar und von Ewigkeit zu Ewigkeit. -

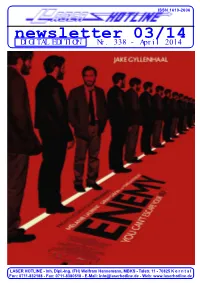

Newsletter 03/14 DIGITAL EDITION Nr

ISSN 1610-2606 ISSN 1610-2606 newsletter 03/14 DIGITAL EDITION Nr. 338 - April 2014 Michael J. Fox Christopher Lloyd LASER HOTLINE - Inh. Dipl.-Ing. (FH) Wolfram Hannemann, MBKS - Talstr. 11 - 70825 K o r n t a l Fon: 0711-832188 - Fax: 0711-8380518 - E-Mail: [email protected] - Web: www.laserhotline.de Newsletter 03/14 (Nr. 338) April 2014 editorial Hallo Laserdisc- und DVD-Fans, liebe Filmfreunde! Es gibt viel zu tun – packen wir’s an! Das zumindest war unsere Devise in den vergangenen Wochen: nicht weni- ger als drei Stuttgarter Kino-Premieren galt es in Bild und Ton für unseren Youtube-Kanal festzuhalten. Dietrich Brüggemanns KREUZWEG, Antje Schneiders & Carsten Waldbauers DIE SCHÖNE KRISTA sowie Thomas Dirnhofers CERRO TORRE – NICHT DEN HAUCH EINER CHANCE hiel- ten unseren Videoschnittplatz auf Trab. Das Ergebnis unseres Premieren- KREUZWEG: Regisseur und Drehbuchautor Dietrich Brüggemann marathons ist bereits online und wir kam zur Premiere seines neuesten Films persönlich nach Stuttgart. freuen uns wie immer auf Ihre Kom- mentare. Aber es gab noch ein weiteres Event, das uns voll in Anspruch genommen hat: die Weltpremiere von REMEMBERING WIDESCREEN, die im Rahmen des “Widescreen Week- ends” in Bradford stattfand. Die Reso- nanz vor fast ausverkauftem Kinosaal war sensationell gut! Die Dokumenta- tion über die “Mutter” aller Breit- format-Filmfestivals wurde vom Publi- kum mit kräftigem Applaus bedacht und sorgte das gesamte Wochenende über für Gesprächsstoff. Die häufigste Frage war jene nach einer DVD oder Blu-ray des Films. Regisseur Wolfram Hannemann dazu: “Wir werden zu ge- gebener Zeit eine DVD und auch eine DIE SCHÖNE KRISTA: im Rahmen einer Kino-Tour machten die Blu-ray des Films veröffentlichen. -

The Flood Narratives in Gen 6-9 and Darren Aronofsky's Film “Noah”

Lee, “Gen 6-9 and Aronofsky’s Film ‘Noah’,” OTE 29/2 (2016): 297-317 297 The Flood Narratives in Gen 6-9 and Darren Aronofsky’s Film “Noah”*1 LYDIA LEE (NORTH-WEST UNIVERSITY, POTCHEFSTROOM CAMPUS) ABSTRACT Since the release of Darren Aronofsky’s film “Noah” in 2014, questions have been raised with regard to the relation between the film and the Bible. This article compares the flood stories in Gen 6- 9 and Aronofsky’s film “Noah.” Probing some interesting and sig- nificant divergences between these two texts, I argue that the film “Noah” offers a good opportunity to discuss the open nature of the biblical texts, which often stimulates further transformations and interpretations. KEY WORDS: Aranofsky, Noah, Gen 6-9, hermeneutics, Pentateuchal criticism, ancient Jewish interpretation. A INTRODUCTION In 2014, the award-winning director Darren Aronofsky transformed a biblical epic into a blockbuster film – “Noah.” Informed by his Jewish upbringing, Aronofsky uses the film to create his own midrash on the Noah story.2 He retells the biblical story of the flood recorded in Gen 6-9, narrating how Noah and his family have endured and survived the flood sent out by the Creator. The film includes a breath-taking scenery, dramatic plot, and above all complex characters. For the general public, a natural curiosity arises with regard to the * Article submitted: 30/05/2016; peer reviewed: 23/06/2016; accepted: 11/07/2016. Lydia Lee, “The Flood Narratives in Gen 6-9 and Darren Aronofsky’s ‘Noah’,” OTE 29/2 (2016): 297-317, doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.17159/23123621 /2016/ v29n2a7 1 My hearty thanks go to Dr. -

Peters C.Indd

NOAH TRADITIONS IN THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS Conversations and Controversies of Antiquity Society of Biblical Literature Early Judaism and Its Literature Judith H. Newman, Series Editor Number 26 NOAH TRADITIONS IN THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS Conversations and Controversies of Antiquity NOAH TRADITIONS IN THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS Conversations and Controversies of Antiquity Dorothy M. Peters Society of Biblical Literature Atlanta NOAH TRADITIONS IN THE DEAD SEA SCROLLS Conversations and Controversies of Antiquity Copyright © 2008 by the Society of Biblical Literature All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by means of any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission should be addressed in writing to the Rights and Permissions Offi ce, Society of Biblical Literature, 825 Houston Mill Road, Atlanta, GA 30329 USA. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Peters, Dorothy M., 1958- Noah traditions in the Dead Sea scrolls : conversations and controversies of antiquity / Dorothy M. Peters. p. cm. — (Early Judaism and its literature ; no. 26) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-58983-390-6 (paper binding : alk. paper) 1. Noah (Biblical fi gure) 2. Dead Sea scrolls. 3. Judaism—History—Post-exilic period, 586 B.C.-210 A.D. I. Title. BS580.N6P48 2008 296.1'55—dc22 2008043301 15 14 13 12 11 10 09 08 5 4 3 2 1 Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, recycled paper conforming to ANSI /NISO Z39.48–1992 (R1997) and ISO 9706:1994 standards for paper permanence.