Of Some Slovenian Supernatural Beings from the Annual Cycle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inter-Group Trust in the Realm of Displacement Suzan Kisaoglu

Master’s Thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies Department of Peace and Conflict Research UPPSALA UNIVERSITET INTER-GROUP TRUST IN THE REALM OF DISPLACEMENT An Investigation into the Long-term Effect of Pre-war Inter-Group Contact on the Condition of Post-War Inter-Group Trust of Internally Displaced People SUZAN KISAOGLU Spring 2021 Supervisor: Annekatrin Deglow Word Count: 19540 ABSTRACT: Inter-group social trust is one of the main elements for peacebuilding and, as a common feature of civil wars, Forced Internal Displacement is creating further complexities and challenges for post-war inter-group social trust. However, research revealed that among the internally displaced people (IDP), some tend to have a higher level of post-war inter-group trust compared to the other IDP. Surprisingly, an analysis based on this topic revealed that only a small number of studies are focusing on the condition of IDP’s post-war intergroup social trust in the long run. Therefore, this study examines the inter-group social trust of internally displaced people to provide a theoretical explanation for the following question; under what conditions the internally displaced people tend to trust more/less the conflicting party in the post-war context? With an examination of social psychology research, this thesis argues that post-war inter-group social trust of IDP who have experienced continuous pre-war inter-group contact will be stronger than the IDP who do not have such inter-group contact experience. The reason behind this expectation is the expected effect of inter-group contact on eliminating the prejudices and promoting the ‘collective knowledge’ regarding the war and displacement, thus promoting inter-group trust. -

Martin Kojc, Most K Spoznanju, KUD Prasila, 2018) 10.40–10.55 Dr

Prleška düša kot uvod v razpravo o Martinu Kojcu Državni svet RS Ljubljana 24. april 2019 10.00–10.20 Pozdravni nagovori Matjaž Švagan, podpredsednik Državnega sveta Jurij Borko, župan Občine Središče ob Dravi Danijel Vrbnjak, župan Občine Ormož Mag. Primož Ilešič, sekretar na Uradu RS za Slovence v zamejstvu in po svetu Dušan Gerlovič, predsednik uprave Ustanove dr. Antona Trstenjaka 10.20–10.40 Helena Srnec, kratka predstavitev knjige Prleška düša kot uvod v razpravo o Martinu Kojcu ter predstavitev Martina Kojca (Martin Kojc, most k spoznanju, KUD Prasila, 2018) 10.40–10.55 dr. Janek Musek, Filozofska fakulteta v Ljubljani, Oddelek za psihologijo – Martin Kojc – duhovni izvori in samoniklost 10.55–11.10 doc. dr. Igor Škamperle, Filozofska fakulteta v Ljubljani, Oddelek za sociologijo – Razumevanje celovitosti osebe v nauku Martina Kojca in pojem individuacije C. G. Junga 11.10–11.20 Jan Brodnjak, A. Diabelli: Sonata v f-duru 11.20–11.35 mag. Blanka Erhartič, Gimnazija Ormož – Kje lahko najde svoje mesto Martin Kojc v splošni gimnaziji? 11.35–11.50 mag. Franc Mikša, veleposlanik v Ministrstvu za zunanje zadeve – Razmišljanje gimnazijca ob branju knjige Martina Kojca Das Lehrbuch des Lebens v letih 1968 in 1969 11.50–12.05 mag. Bojan Šinko, Zasebna klinična psihološka ambulanta, pranečak M. Kojca – Martin Kojc skozi oči pranečaka 12.05–12.20 Razprava 12.20–13.00 Pogostitev Prleška düša kot uvod v razpravo o Martinu Kojcu Prleška düša; severovzhodna Slovenija s poudarkom na Prlekiji: prleški ustvarjalci in Prlekija v literarnih delih -

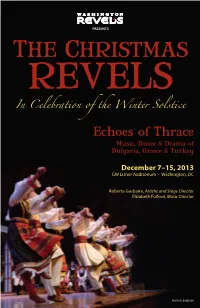

Read This Year's Christmas Revels Program Notes

PRESENTS THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey December 7–15, 2013 GW Lisner Auditorium • Washington, DC Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director PHOTO BY ROGER IDE THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey The Washington Featuring Revels Company Karpouzi Trio Koleda Chorus Lyuti Chushki Koros Teens Spyros Koliavasilis Survakari Children Tanya Dosseva & Lyuben Dossev Thracian Bells Tzvety Dosseva Weiner Grum Drums Bryndyn Weiner Kukeri Mummers and Christmas Kamila Morgan Duncan, as The Poet With And Folk-Dance Ensembles The Balkan Brass Byzantio (Greek) and Zharava (Bulgarian) Emerson Hawley, tuba Radouane Halihal, percussion Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director Gregory C. Magee, Production Manager Dedication On September 1, 2013, Washington Revels lost our beloved Reveler and friend, Kathleen Marie McGhee—known to everyone in Revels as Kate—to metastatic breast cancer. Office manager/costume designer/costume shop manager/desktop publisher: as just this partial list of her roles with Revels suggests, Kate was a woman of many talents. The most visibly evident to the Revels community were her tremendous costume skills: in addition to serving as Associate Costume Designer for nine Christmas Revels productions (including this one), Kate was the sole costume designer for four of our five performing ensembles, including nineteenth- century sailors and canal folk, enslaved and free African Americans during Civil War times, merchants, society ladies, and even Abraham Lincoln. Kate’s greatest talent not on regular display at Revels related to music. -

January 2014

01 ISSN 1854-0805 January 2014 The latest from Slovenia IN FOCUS INTERVIEW: Petra Majdič - Coaches and competitors must have the best conditions IN FOCUS: Prehistoric skiing at Bloke BUSINESS: Elan - The most innovative brand E-book . Read it anywhere. 12 ISSN 1854-0805 December 2013 The latest from Slovenia 11 November 2013 The latest from Slovenia ISSN 1854-0805 In 2014 also available in .iBooks format Philippe Starck ON THE POLITICAL AGENDA INTERVIEW: Miroslav Mozetič, MSc INTERVIEW: The GovernmentBUSINESS wins a vote of confidence IN FOCUS INTERVIEW: Dr Bojana Rogelj Škafar HERITAGE: Slovenian Potica : Miha Klinar ON THE POLITICAL AGENDA: IN FOCUS INTERVIEW You can enjoy reading Sinfo on an Apple computer, iPad or iPhone FOR FREE. An electronic edition of Sinfo in the .iBooks format is now accessible in 51 Apple iBookstores worldwide, including the United States, Japan, Brazil, Australia and the European Union. Sinfo in PDF is available on Android and Windows computers, tablets, and also on Android and Windows phones via the Sinfo webpage. Sinfo will be available simultaneously with the publication of the printed version. CONTEnts EDITORIAL IN FOCUS INTERVIEW 12 Photo: Bruno Toič Petra Majdič Coaches and competitors must have the best conditions A aniel Novaković/ST D Photo: Photo: IN FOCUS 17 Prehistorical skiing at Bloke Tanja Glogovčan, editor Are Slovenians really a skiing nation? M E rchives of S rchives A Photo: Photo: A nation of sporting greats This issue focuses in particular on the forthcoming Winter Olympics scheduled to take place in February. It features an interview with Petra Majdič, the head of the Slovenian Olympic team, in which she talks about her experience as an Olympic competitor and outlines her expectations for the 2014 Winter Olympics in Sochi. -

Spomenik Škofu Antonu Martinu Slomšku V Azilu Mariborske Stolnice

ACTA HISTORIAE ARTIS SLOVENICA 18|1 2013 UMETNOSTNOZGODOVINSKI INŠTITUT FRANCETA STELETA ZRC SAZU 2013 1 | 18 Vsebina • Contents Ana Kostić, Public Monuments in Sacred Space. Memorial Tombs as National Monuments in Nineteenth Century Serbia Ceremony of the unveiling of Milica Stojadinović-Srpkinja’s • Javni spomeniki v sakralnem prostoru. Spominske grobnice kot nacionalni spomeniki v Srbiji v 19. stoletju monument, Vrdnik Monastery (detail) Ana Lavrič, »Javni« spomenik škofu Antonu Martinu Slomšku v azilu mariborske stolnice • The “Public” Monument of Anton Martin Slomšek under the Shelter of Maribor Cathedral Polona Vidmar, Lokalpatriotismus und Lokalpolitik. Die Denkmäler Wilhelms von Tegetthoff, Kaiser Josefs II. sowie Erzherzog Johanns in Maribor und die Familie Reiser • Lokalni patriotizem in lokalna politika. Spomeniki Wilhelmu Tegetthoffu, cesarju Jožefu II. in nadvojvodi Janezu v Mariboru ter vpliv družine Reiser Nenad Makuljević, Funeral Culture and Public Monuments. Jernej Kopitar, Vuk Karadžić and Creating a Common Serbo-Slovenian Culture of Memory • Pogrebne slovesnosti in javni spomeniki. Kopitar, Karadžić in ustvarjanje ACTA HISTORIAE ARTIS SLOVENICA skupne srbsko-slovenske kulture spominjanja Irena Ćirović, Memory, Nation and a Heroine of the Modern Age. Monument to Milica Stojadinović-Srpkinja • Spomin, nacija in herojinja moderne dobe. Spomenik Milici Stojadinović - Srpkinji ACTA HISTORIAE ARTIS SLOVENICA Establishing National Identity in Public Space Public Monuments in Slovenia and Serbia in the Nineteenth Century -

Prenos Pdf Različice Dokumenta

POŠTNINA PLAČANA PRI POŠTI 9244 SVETI JURIJ OB ŠČAVNICI JOVŠKO glasilo JÜRGLASILO OBČINE SVETI JURIJ OB ŠČAVNICI / DECEMBER 2017 Iz vsebine: PRAVLJICA • Županov nagovor Sneži kot v pravljici, a nikjer beline, • Priznanja župana za pomembne dosežke v meni le črnina. • 200-letnica rojstva rojaka Davorina Trstenjaka Koliko dni bo še tako, • Pregled dogodkov iz druge polovice leta 2017 hladno, snežno in črno? Želim si le, • Predpraznični utrinki da vse slabo iz spomina bi ušlo. Spomin … naj gre! Ogrejejo naj se roke. Snegu naj vrne se belina, zgladi v mojem srcu se praznina. Naj pospeši ritem se srca, naj v soju sonca in snega mi nasproti pride moja ljubljena. (Boštjan Petučnik, Pesmi sivega laboda) Prejemniki priznanj za leto 2017 Na prednovoletnem sprejemu je bilo za izjemne dosežke v letu 2017 podeljenih 11 priznanj. Prejeli so jih: Foto: Ludvik KRAMBERGER Ekipa Twirling kluba Sv. Jurij ob Ščavnici, ki je na državnem tekmovanju dosegla odlične rezultate z »zlato« Nino Novak – letošnjo najmlajšo prejemnico PRIZNANJA ŽUPANA za pomembne dosežke Foto: Klavdija BEC 2 DECEMBER 2017 JOVŠKO UVODNIK, NAGOVOR ŽUPANA JÜRglasilo Nekoga moraš imeti rad, Te tople, božajoče, po ljubezni do sočloveka diše- pa čeprav trave, reko, drevo ali kamen, če besede pesnika Ivana Minattija so kot žarek son- nekomu moraš nasloniti roko na ramo, ca v temnih turobnih jesenskih dneh. Naj nas te da se, lačna, nasiti bližine, besede vedno, vsak dan znova, spomnijo, da je ne- nekomu moraš, moraš, kje še nekdo, ki nas potrebuje, ki ga imamo radi, to je kot kruh, kot požirek vode, ki nas ima rad, ki nam ponuja stisk roke, ki nas moraš dati svoje bele oblake, vabi v svoj objem ‒ verjemite, veliko takih lju- svoje drzne ptice sanj, di je med nami. -

Sotiroula Yiasemi Dissertation Submitted for the Award of a Phd

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH STUDIES TRANSLATING CHILDREN’S LITERATURE IN A CHANGING WORLD: Yiasemi AND ITS ARTICULATIONS INTO GREEK Sotiroula Yiasemi Dissertation submitted for the award of a PhD degree at the University of Cyprus Sotiroula February, 2012 © SOTIROULA YIASEMI Yiasemi Sotiroula ΣΕΛΙΔΑ ΕΓΚΥΡΟΤΗΤΑΣ • Υποψήφιος Διδάκτορας: ΣΩΤΗΡΟΥΛΑ ΓΙΑΣΕΜΗ • Τίτλος Διατριβής: Translating Children’s Literature in a Changing World: Potteromania and its Articulations into Greek • Η παρούσα Διδακτορική Διατριβή εκπονήθηκε στο πλαίσιο των σπουδών για απόκτηση Διδακτορικού Διπλώματος στο Τμήμα Αγγλικών Σπουδών, στο πρόγραμμα Μεταφραστικών Σπουδών και εγκρίθηκε στις 24 Φεβρουαρίου 2012 από τα μέλη της Εξεταστικής Επιτροπής. • Εξεταστική Επιτροπή: o Ερευνητικός Σύμβουλος: Στέφανος Στεφανίδης, Καθηγητής, Τμήμα Αγγλικών Σπουδών, Πανεπιστήμιο Κύπρου o Άλλα Μέλη: Gillian Lathey, Καθηγήτρια, University of Roehampton, UK Διονύσης Γούτσος, ΑναπληρωτήςYiasemi Καθηγητής, Τμήμα Γλωσσολογίας, Φιλοσοφική Σχολή, Πανεπιστήμιο Αθηνών Γιώργος Φλώρος, Επίκουρος Καθηγητής, Τμήμα Αγγλικών Σπουδών, Πανεπιστήμιο Κύπρου Ευθύβουλος (Φοίβος) Παναγιωτίδης, Επίκουρος Καθηγητής, Τμήμα Αγγλικών Σπουδών, Πανεπιστήμιο Κύπρου Sotiroula i PAGE OF VALIDATION • Doctoral candidate: SOTIROULA YIASEMI • The title of the dissertation: Translating Children’s Literature in a Changing World: Potteromania and its Articulations into Greek • This dissertation was submitted in fulfillment of the requirements of the PhD programme in Translation Studies in the Department of English Studies and approved -

Mojca Kreft MED SPOMINI, GLEDALIŠČEM in LITERATURO

1 Mojca Kreft MED SPOMINI, GLEDALIŠČEM IN LITERATURO. Vinjeta za Bratka Krafta. I. Bratka Krefta se spominjam iz svojih otroških let, ko je prihajal k nam na obiske k nam domov, predvsem pa, ko je bival v zidanici na Kreftovem vrhu, ali pa, ko smo pešačili k dedku in babici. To ni bil kraj, Vrh so bile gorice, vinograd z zidanico in pripadajočo stiskalnico in viničarijo. Včasih pa smo rekli kar, gremo v Murščak. Pravzaprav se je kraj imenoval Hrašenski vrh, Murščakov sosed . Iz zgornjega dela Biserjan, kjer smo prebivali, v vasi ob Ščavnici, je do Kreftovega vrha tekla pešpot, méšnica, po njej so hodili ljudje k maši, otroci pa v šolo, med njivami, po jezéh in preko brví, mimo Banjkovec, čez Črnce in Ščavnico skozi Dragotince in preko Róžičkega vrha, mimo vinogradov/goric, zidanic z viničarijami in cimpračami, skozi Stánetince in po dedkovi šumi navkreber med njegovimi goricami do Vrha. Hoja je potekala po dolinah in bregéh, navzdol in navzgor, po ilovnatih kolovozih in cestah, po rumenem asfaltu, kot so te poti šaljivo imenovali domačini. Kakor se pač razprostirajo Slovenske Gorice s svojimi, v tistih časih še bogatimi kmetijami v dolinah in v ponosni revščini se razvijajoče viničarske vasi po vrhéh, vsake s svojimi zgodbami in skupnimi usodami, ki so prav gotovo navdihovale Bratka pri njegovih povestih za Kalvarijo za vasjo. Ljudje so vedeli, kdaj da je Bratko v vrhu, saj so ga vsi poznali, bil jim 2 je ljub sosed, domačin, gosposko oblečen, ali nikoli gospod, kot so rekli. Bil je domač in z vsemi se je pogovarjal. -

Kresnik: an Attempt at a Mythological Reconstruction

Kresnik: An Attempt at a Mythological Reconstruction Zmago Šmitek The Slovene Kresnik tradition has numerous parallels in Indo-European mythologies. Research has established connections between the myth about a hero’s fight with a snake (dragon) and the vegetational cult of Jarilo/Zeleni Jurij. The Author establishes a hypothesis about Iranian influences (resemblance to figures of Yima/Yama and Mithra) and outlines a later transformation of Kresnik in the period of Christianization. If it is possible to find a mythological figure in Slovene folk tradition which is remi- niscent of a “higher” deity, this would undoubtedly be Kresnik. It is therefore not strange that different researchers were of the opinion that Kresnik represented the key to old Slovene mythology and religion.1 Their explanations, however, are mostly outdated, insufficciently explained or contrasting in the context of contemporary findings of comparative mythol- ogy and religiology. Equally doubtful is also the authenticity of older records about Kresnik since the still living traditions seem not to verify them.2 Kresnik thus remains a controver- sial and mysterious image as far as the origin of his name is concerned, but also concerning the role and the function it was supposed to have in old Slovene, Slavic and Indo-European mythological structures. The first extensive and thorough comparative study about Kr(e)snik was written by Maja Bošković-Stulli.3 She justly ascertained that there were differences between the major- ity of Slovene records on Kresnik and the data on a being with the same name collected in Croatia and east of it. On the other hand, however, certain fragments of Slovene tradition did correspond to the image of Krsnik which she had documented during the course of her 1 Kresnik was linked to Božič or Svarožič (Jakob Kelemina, Bajke in pripovedke slovenskega ljudstva, Znanstvena knjižnica, Tome 4, Celje 1930, p. -

The Christmas Troll and Other Yuletide Stories

The Christmas Troll and Other Yuletide Stories Clement A. Miles Varla Ventura Magical Creatures A Weiser Books Collection This ebook edition first published in 2011 by Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC. With offices at: 665 Third Street, Suite. 400 San Francisco, CA 94107 www.redwheelweiser.com Copyright © 2011 by Red Wheel/Weiser llc. All rights reserved. Excerpted from Christmas in Ritual and Tradition, Christian and Pagan by Clement A. Miles. T. Fisher Unwin, 1912. eISBN: 978-1-61940-014-6 Cover design by Jim Warner Things That Go Bump in the Night before Christmas What young child doesn’t love the din of Christmas? The lights in shop windows and holiday hum, a promise of bellies full of cookies and piles of presents. And when most of us think of Christmas we think of a bearded man in a red suit, jolly and adept at delivering toys. We accept his magical elfin assistants and flying abilities in a way that goes almost unquestioned, chalking it up to the “magic of the season.” And when we think of holiday horrors it is usually high prices or forgotten presents, perhaps a burnt Christmas ham. What would your children say if you whispered tales to them not of Christmas cheer and sightings of the elusive Santa Claus, but stories of a different kind of magic altogether? What if you told them that at the stroke of midnight on Christmas Eve, curious things happen: Wells run with blood. Animals talk. Buried treasures are revealed and water turns to wine. And if you warned them of witches that leapt from roof to roof, or ghosts that hung about the chimneys waiting to visit them in the dark of the night, would they still anticipate the winter holidays in the same way? Early 20th century author Clement A. -

Bowb Edition-Digital Compr.Pdf

TradiTion anew! PB 1 BIENNALE OF WESTERN by the theme of patterns, which initiated the BALKANS creation of large-scale installations (pavilions) in public space, for hosting community lead activities and fostering civic engagement. The programme The Biennale of Western Balkans (BoWB) is contained three exhibitions exploring concepts a biennial festival and year-round project, and practices linked to immaterial cultural forms and ephemeral traditions: the concept of myth and of Epirus-Northwestern Greece, in October collective narratives, the craft of weaving throughout 2018. It is an initiative of the History of Art history and community memory through sound; a Laboratory of the School of Fine Arts in series of three conferences with talks on intangible the University of Ioannina. Its vision is to cultural heritage, cultural ecology and the commons, link intangible cultural heritage with and educational workshops promoting open contemporary art in multivalent, collective experimentation with traditional craftsmanship and and affective ways, inspiring people to digital tools. experience tradition anew, in connection During the festival more than 100 scientists, artists, with technology. makers and cultural professionals were invited BoWB aims to develop inclusive to Ioannina, many of whom visited the city for participation in a wide range of social groups and foster a network of transnational and with universities, research institutions, cultural intersectional mobility in Greece and the organisations, communities and initiatives from Western Balkans. Its mission is to support Greece, Europe and the Western Balkans emerged, interdisciplinary projects that further explore while around 200 people signed up as volunteers. concepts as community practices, well- being, open technologies, cultural ecology and digital cultural heritage. -

Knjižeyna Zgodovina Slovenskega Stajerja

Knjižeyna zgodovina Slovenskega Stajerja. ; m Spisal Ivan Macun. Pisatelj pridržuje si vse postavne pravice. = i j S V Gradcu. "(p> Založil in na svetlo dal pisatelj. 1883. Književna z Slovenskega Štajerja. Spisal Ivan Maciui. Pisatelj pridržuje si vse postavne prav V Gradcu. Založil in 11 a svetlo dal pisatelj. 1883. Natis o<J tiskarnice Stvria v Gradcu Veleumu stoječemu na vrhu slovanskih jezikoslovcev, sinu slovenskega Štajerja, DE F. MIKLOŠIČU, vitezu, dvorskemu svetovalcu, članu mnogih akademij za znanosti, profesorja slovanskega jezikoslovja in književnosti na bečkem vseučilišču, posvečuje o njegovi sedemdesetletnici književno svojo zgodovino slovenskega Štajerja v najglobokejsem štovanju in prisrčni udanosti zemljak Ivan Macun. Predgovor, Habet sua fata libellus! Zibeljko je knjigi tesal dr. Vošnjak pozivom dne 8. marca leta 1867., ali bi jaz za „Slovenski Štajer", ki ga je namenila na svetlo davati Slovenska Matica, napisal književno zgodovino. Drage volje sprejevsi poziv najavil sem leta 1870. Matici, da je sestavek dogotovljen. Odgovorilo se mi je, da je Matica, ki je leta 1868. bila na svetlo dala največi del prvega snopiča, za leto 1870. pak tret- jega, dalnje izdavanje Slovenskega Štajerja odložila za poznej, ter se je še le leta 1880. zopet spomnila pre- vzete si naloge. — Z nova predloženo delo opetovano je sprejela in zopet odložila Matica za poznej. Ko pak je početkom tekočega leta sklenola, da le četiri pole za leto 1882. pridejo na svetlo, ostalo pak drugi krat, tega nesem mogel nikakor dopustiti/in tako delo sedaj prihaja mojim trudom in na moje troške na svetlo. In jasno tukaj naglašujem, da je po tem marsikaj pri- dobilo na dobro stran.