Sotiroula Yiasemi Dissertation Submitted for the Award of a Phd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inter-Group Trust in the Realm of Displacement Suzan Kisaoglu

Master’s Thesis in Peace and Conflict Studies Department of Peace and Conflict Research UPPSALA UNIVERSITET INTER-GROUP TRUST IN THE REALM OF DISPLACEMENT An Investigation into the Long-term Effect of Pre-war Inter-Group Contact on the Condition of Post-War Inter-Group Trust of Internally Displaced People SUZAN KISAOGLU Spring 2021 Supervisor: Annekatrin Deglow Word Count: 19540 ABSTRACT: Inter-group social trust is one of the main elements for peacebuilding and, as a common feature of civil wars, Forced Internal Displacement is creating further complexities and challenges for post-war inter-group social trust. However, research revealed that among the internally displaced people (IDP), some tend to have a higher level of post-war inter-group trust compared to the other IDP. Surprisingly, an analysis based on this topic revealed that only a small number of studies are focusing on the condition of IDP’s post-war intergroup social trust in the long run. Therefore, this study examines the inter-group social trust of internally displaced people to provide a theoretical explanation for the following question; under what conditions the internally displaced people tend to trust more/less the conflicting party in the post-war context? With an examination of social psychology research, this thesis argues that post-war inter-group social trust of IDP who have experienced continuous pre-war inter-group contact will be stronger than the IDP who do not have such inter-group contact experience. The reason behind this expectation is the expected effect of inter-group contact on eliminating the prejudices and promoting the ‘collective knowledge’ regarding the war and displacement, thus promoting inter-group trust. -

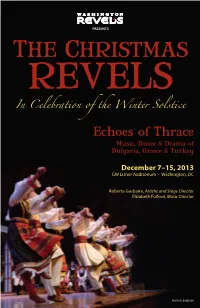

Read This Year's Christmas Revels Program Notes

PRESENTS THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey December 7–15, 2013 GW Lisner Auditorium • Washington, DC Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director PHOTO BY ROGER IDE THE CHRISTMAS REVELS In Celebration of the Winter Solstice Echoes of Thrace Music, Dance & Drama of Bulgaria, Greece & Turkey The Washington Featuring Revels Company Karpouzi Trio Koleda Chorus Lyuti Chushki Koros Teens Spyros Koliavasilis Survakari Children Tanya Dosseva & Lyuben Dossev Thracian Bells Tzvety Dosseva Weiner Grum Drums Bryndyn Weiner Kukeri Mummers and Christmas Kamila Morgan Duncan, as The Poet With And Folk-Dance Ensembles The Balkan Brass Byzantio (Greek) and Zharava (Bulgarian) Emerson Hawley, tuba Radouane Halihal, percussion Roberta Gasbarre, Artistic and Stage Director Elizabeth Fulford, Music Director Gregory C. Magee, Production Manager Dedication On September 1, 2013, Washington Revels lost our beloved Reveler and friend, Kathleen Marie McGhee—known to everyone in Revels as Kate—to metastatic breast cancer. Office manager/costume designer/costume shop manager/desktop publisher: as just this partial list of her roles with Revels suggests, Kate was a woman of many talents. The most visibly evident to the Revels community were her tremendous costume skills: in addition to serving as Associate Costume Designer for nine Christmas Revels productions (including this one), Kate was the sole costume designer for four of our five performing ensembles, including nineteenth- century sailors and canal folk, enslaved and free African Americans during Civil War times, merchants, society ladies, and even Abraham Lincoln. Kate’s greatest talent not on regular display at Revels related to music. -

Of Some Slovenian Supernatural Beings from the Annual Cycle

From Tradition to Contemporary Belief Tales: Th e “Changing Life” of Some Slovenian Supernatural Beings from the Annual Cycle Monika Kropej Th e article addresses the oral tradition and tales about certain Slovenian supernatural beings that accompany the annual cycle and its turning points: midsummer and midwinter solstice as well as spring and autumn changing shift s. Discussed are the changing images of these folk belief narratives resulting from continuously changing cultural and social contexts, while supernatural fi gures or spirits acquire a demythicised image in contemporary belief tales and urban legends. Slovenian folk belief legends feature over one hundred and fi ft y diff erent super- natural beings, among them the supernatural beings of nature, restless souls, demons and ghosts, mythical animals and cosmological beings. Th e supernatural beings here presented accompany the yearly turning points: the summer and the winter solstices, the spring equinox, and the conclusion of the autumn. Containing a wide variety of motifs, folk belief legends about these supernatural beings have undergone continuous changes due to the diff erent cultural and social contexts. Kresnik and the Summer Apparitions Th e summer solstice is connected with a number of customs and beliefs that are similar throughout Europe. In Slovenia, a characteristic supernatural being that makes an appearance during this period is Kresnik (Krsnik, Krstnik, Šentjanževec). Kresnik’s at- tributes are the sun and the fi re (in Slovene, kresati denotes to kindle fi re by striking). Judging by these attributes and narrative tradition, Russian philologist Nikolai Mikhailov established Kresnik’s similarity with the principal Slavic God Perun, the Th under God and the conqueror of Veles. -

The Christmas Troll and Other Yuletide Stories

The Christmas Troll and Other Yuletide Stories Clement A. Miles Varla Ventura Magical Creatures A Weiser Books Collection This ebook edition first published in 2011 by Red Wheel/Weiser, LLC. With offices at: 665 Third Street, Suite. 400 San Francisco, CA 94107 www.redwheelweiser.com Copyright © 2011 by Red Wheel/Weiser llc. All rights reserved. Excerpted from Christmas in Ritual and Tradition, Christian and Pagan by Clement A. Miles. T. Fisher Unwin, 1912. eISBN: 978-1-61940-014-6 Cover design by Jim Warner Things That Go Bump in the Night before Christmas What young child doesn’t love the din of Christmas? The lights in shop windows and holiday hum, a promise of bellies full of cookies and piles of presents. And when most of us think of Christmas we think of a bearded man in a red suit, jolly and adept at delivering toys. We accept his magical elfin assistants and flying abilities in a way that goes almost unquestioned, chalking it up to the “magic of the season.” And when we think of holiday horrors it is usually high prices or forgotten presents, perhaps a burnt Christmas ham. What would your children say if you whispered tales to them not of Christmas cheer and sightings of the elusive Santa Claus, but stories of a different kind of magic altogether? What if you told them that at the stroke of midnight on Christmas Eve, curious things happen: Wells run with blood. Animals talk. Buried treasures are revealed and water turns to wine. And if you warned them of witches that leapt from roof to roof, or ghosts that hung about the chimneys waiting to visit them in the dark of the night, would they still anticipate the winter holidays in the same way? Early 20th century author Clement A. -

Bowb Edition-Digital Compr.Pdf

TradiTion anew! PB 1 BIENNALE OF WESTERN by the theme of patterns, which initiated the BALKANS creation of large-scale installations (pavilions) in public space, for hosting community lead activities and fostering civic engagement. The programme The Biennale of Western Balkans (BoWB) is contained three exhibitions exploring concepts a biennial festival and year-round project, and practices linked to immaterial cultural forms and ephemeral traditions: the concept of myth and of Epirus-Northwestern Greece, in October collective narratives, the craft of weaving throughout 2018. It is an initiative of the History of Art history and community memory through sound; a Laboratory of the School of Fine Arts in series of three conferences with talks on intangible the University of Ioannina. Its vision is to cultural heritage, cultural ecology and the commons, link intangible cultural heritage with and educational workshops promoting open contemporary art in multivalent, collective experimentation with traditional craftsmanship and and affective ways, inspiring people to digital tools. experience tradition anew, in connection During the festival more than 100 scientists, artists, with technology. makers and cultural professionals were invited BoWB aims to develop inclusive to Ioannina, many of whom visited the city for participation in a wide range of social groups and foster a network of transnational and with universities, research institutions, cultural intersectional mobility in Greece and the organisations, communities and initiatives from Western Balkans. Its mission is to support Greece, Europe and the Western Balkans emerged, interdisciplinary projects that further explore while around 200 people signed up as volunteers. concepts as community practices, well- being, open technologies, cultural ecology and digital cultural heritage. -

Greek- Americans N C V a Weekly Greek-American Publication VOL

S o C V ΓΡΑΦΕΙ ΤΗΝ ΙΣΤΟΡΙΑ Bringing the news W ΤΟΥ ΕΛΛΗΝΙΣΜΟΥ to generations of E ΑΠΟ ΤΟ 1915 The National Herald Greek- Americans N c v a WeekLy greek-american PubLication www.thenationalherald.com VOL. 15, ISSUE 782 October 6-12 , 2012 $1.50 Remembering Paddy: Inauguration of an Outdoor Theater at UConn Patrick Leigh Fermor, Paideia Launches Theater at Center Battle of Crete Hero of Greek Studies By Lawrence Osborne By Theodore Kalmoukos Wall Street Journal TNH Staff Writer A famous anecdote, told by Patrick Leigh Fermor himself in his STORRS CT –The Hellenic Or - book Mani, relates how on one furnace-hot evening in the town of ganization Paideia inaugurated Kalamata, in the remote region for which that book is named, Fer - its new outdoors theater at its mor and his dinner companions picked up their table and carried Center of Greek Studies on the it nonchalantly and fully dressed into the sea. It is a few years campus of the University of Con - after World War II, and the English are still an exotic rarity in this necticut on September 29. The part of Greece. There they sit until the waiter arrives with a plate theater is a depiction of the An - of grilled fish, looks down at the displaced table and calmly—with cient Greek theater of Epidavros an unflappable Greek stoicism—wades into the water to serve din - with the orchestra, a two-story ner. Soon the diners are surrounded by little boats and out come stage and colonnade. It was the bouzouki and the wine. -

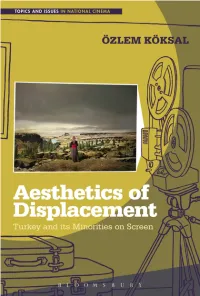

Aesthetics of Displacement Topics and Issues in National Cinema Volume 4 Aesthetics of Displacement: Turkey and Its Minorities on Screen

Aesthetics of Displacement Topics and Issues in National Cinema volume 4 Aesthetics of Displacement: Turkey and its Minorities on Screen Series Editor: Armida de la Garza, University College Cork, Ireland Editorial Board: Mette Hjort, Chair Professor and Head, Visual Studies Lingnan University, Hong Kong Lúcia Nagib, Professor of Film, University of Reading, UK Chris Berry, Professor of Film Studies, Kings College London, UK, and Co-Director of the Goldsmiths Leverhulme Media Research Centre, UK Sarah Street, Professor of Film and Foundation Chair of Drama, University of Bristol, UK Jeanette Hoorn, Professor of Visual Cultures, University of Melbourne, Australia Shohini Chaudhuri, Senior Lecturer and MA Director in Film Studies, University of Essex, UK Other volumes in the series: Volume 1: Revolution and Rebellion in Mexican Film by Niamh Th ornton Volume 2: Ecology and Contemporary Nordic Cinemas: From Nation-Building to Ecocosmopolitanism by Pietari Kääpä Volume 3: Cypriot Cinemas edited by Costas Constandinides and Yiannis Papadakis Volume 4: Aesthetics of Displacement by Özlem Köksal Volume 5: Film Music in ‘Minor’ National Cinemas edited by Germán Gil-Curiel Aesthetics of Displacement: Turkey and its Minorities on Screen Özlem Köksal Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Inc 1385 Broadway 50 Bedford Square New York London NY 10018 WC1B 3DP USA UK www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2016 Paperback edition fi rst published 2017 © Özlem Köksal, 2016 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. -

Covering and Discovering: Non-Muslim Minorities and Film." Aesthetics of Displacement: Turkey and Its Minorities on Screen

Köksal, Özlem. "Covering and Discovering: Non-Muslim Minorities and Film." Aesthetics of Displacement: Turkey and its Minorities on Screen. New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016. 63– 92. Topics and Issues in National Cinema. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 30 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501306471.ch-003>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 30 September 2021, 21:57 UTC. Copyright © Özlem Köksal 2016. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 3 Covering and Discovering: Non-Muslim Minorities and Film “All ideas of nation and peoplehood rely on some idea of ethnic purity or singularity and the suppression of the memories of plurality” writes Appadurai (1996: 45). Whether ethnic, religious or otherwise, minorities function as a reminder of “social uncertainties” that cause hostility, and in some cases violence, against the minorities. This is due to the idea of purity and totality inherent in the idea of nation-state, or any other form of social identity put forward by an institution. However, the idea of the totality of a nation is as constructed as the concept of minority. What is more, not only are the nation and national unity constructed but their perception and performance depend on various factors, such as social and economic background. Although Europe, and much of the world, has been dealing with rising nationalisms, and the ascent of the far right, there is also a growing desire to recognize and under- stand the other. -

Download .Pdf Document

JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 1 what’s who? JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 2 JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 3 New edition, revised and enlarged what’s who? A Dictionary of things named after people and the people they are named after Roger Jones and Mike Ware JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 4 Copyright © 2010 Roger Jones and Mike Ware The moral right of the author has been asserted. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. Matador 5 Weir Road Kibworth Beauchamp Leicester LE8 0LQ, UK Tel: (+44) 116 279 2299 Fax: (+44) 116 279 2277 Email: [email protected] Web: www.troubador.co.uk/matador ISBN 978 1848765 214 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data. A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. Typeset in 11pt Garamond by Troubador Publishing Ltd, Leicester, UK Matador is an imprint of Troubador Publishing Ltd JonesPrelims_Layout 1 24/09/2010 10:18 Page 5 This book is dedicated to all those who believe, with the authors, that there is no such thing as a useless fact. -

Pages on Dionysios Solomos Moderngreek.Qxd 19-11-02 2:15 Page 2

ModernGreek.qxd 19-11-02 2:15 Page 1 MODERN GREEK STUDIES (AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND) Volume 10, 2002 A Journal for Greek Letters Pages on Dionysios Solomos ModernGreek.qxd 19-11-02 2:15 Page 2 Published by Brandl & Schlesinger Pty Ltd PO Box 127 Blackheath NSW 2785 Tel (02) 4787 5848 Fax (02) 4787 5672 for the Modern Greek Studies Association of Australia and New Zealand (MGSAANZ) Department of Modern Greek University of Sydney NSW 2006 Australia Tel (02) 9351 7252 Fax (02) 9351 3543 E-mail: [email protected] ISSN 1039-2831 Copyright in each contribution to this journal belongs to its author. © 2002, Modern Greek Studies Association of Australia All rights reserved. No parts of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical or otherwise without the prior permission of the publisher. Typeset and design by Andras Berkes Printed by Southwood Press, Australia ModernGreek.qxd 19-11-02 2:15 Page 3 MODERN GREEK STUDIES ASSOCIATION OF AUSTRALIA & NEW ZEALAND (MGSAANZ) ETAIREIA NEOELLHNIKWN SPOUDWN AUSTRALIAS KAI NEAS ZHLANDIAS President: Vrasidas Karalis, University of Sydney, Sydney Vice-President: Maria Herodotou, La Trobe University, Melbourne Secretery: Chris Fifis, La Trobe University, Melbourne Treasurer: Panayota Nazou, University of Sydney, Sydney Members: George Frazis (Adelaide), Elizabeth Kefallinos (Sydney), Andreas Liarakos (Melbourne), Mimis Sophocleous (Melbourne), Michael Tsianikas (Adelaide) MGSAANZ was founded in 1990 as a professional association by those in Australia and New Zealand engaged in Modern Greek Studies. Membership is open to all interested in any area of Greek studies (history, literature, culture, tradition, economy, gender studies, sexualities, linguistics, cinema, Diaspora, etc). -

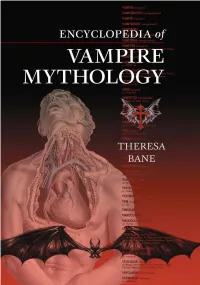

Encyclopedia of Vampire Mythology This Page Intentionally Left Blank Encyclopedia of Vampire Mythology

Encyclopedia of Vampire Mythology This page intentionally left blank Encyclopedia of Vampire Mythology THERESA BANE McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Bane, Theresa, ¡969– Encyclopedia of vampire mythology / Theresa Bane. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-4452-6 illustrated case binding : 50# alkaline paper ¡. Vampires—Encyclopedias. I. Title. GR830.V3B34 2010 398.21'003—dc22 2010015576 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2010 Theresa Bane. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover illustration by Joseph Maclise, from his Surgical Anatomy, 1859 Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 6¡¡, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com To my father, Amedeo C. Falcone, Noli nothi permittere te terere. This page intentionally left blank Table of Contents Preface 1 Introduction 7 THE ENCYCLOPEDIA 13 Bibliography 155 Index 183 vii This page intentionally left blank Preface I am a vampirologist—a mythologist who specializes in cross- cultural vampire studies. There are many people who claim to be experts on vampire lore and legend who will say that they know all about Vlad Tepes and Count Dracula or that they can name several different types of vampiric species. I can do that, too, but that is not how I came to be a known vam- pirologist. Knowing the “who, what and where” is one thing, but knowing and more impor- tantly understanding the “why” is another. -

MSFAU Journal of Social Sciences Cilt 2 Sayı 17

Sosyal Bilimler of Social Sciences Cilt 2 Sayı 17/ Bahar 2018 Journal MSGSÜ Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi - MSFAU MSGSÜ Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi MSFAU Journal of Social Sciences SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ DERGİSİ Cilt 2 Sayı 17/ Bahar 2018 Vol 2 Issue 17/ Spring 2018 Sayı 14 / Güz 2016 ISSN 1309-4815 ?????????????????????? SES / SOUND Sunuş: Sesli Düşünmek Introduction: Thinking Aloud Begüm Özden Fırat Toplumsal Bedenden Çıkan Tekinsiz Sesler: Gezi’nin Estetiği ya da ‘tıktıktıktıktıktık’lar The Uncanny Sounds Emanating from the Social Body: The Aesthetics of Gezi or the ‘ticktickticktickticktick’s Burak Üzümkesici “Magnetic Voice”: Resonance and the Politics of Art “Mıknatıs Ses”: Rezonans ve Sanatın Politikası Nermin Saybaşılı Sesin Görüntüsü / Görüntünün Sesi Image of Sound / Sound of Image Berna Karaçalı Refusing Into-Nation: An Inquiry about Voice, Politics and Resistance Entonasyon’u Reddediş: Ses, Politika ve Direniş Üzerine Bir İnceleme Ege Akdemir Ses Üzerine Bir Atölye Çalışması A Workshop on Sound Güneş Terkol ve Deniz Ulusoy Uygarlığın Sessizliği: 1930’larda Türkiye’de Basılmış Adab-ı Muaşeret Kitaplarında Ses The Silence of Civilization: Voice in the 1930s Etiquette Books Published in Turkey Tülin Ural Kakofoni: Denetim Gürültüsünü Açığa Çıkarmak Cacophony: Revealing The Noise of Control Ebru Yetişkin Gizli Dinlemenin Tarihsel Seyri: Kültürel Teknikler, Ses Teknolojileri ve İşitsel Denetim Historical Trajectory Of Eavesdropping: Cultural Techniques, Sound Technologies and Acoustic Control Sidar Bayram Aesthetics of Silence and the