BUILDING WORKER-TO-WORKER SOLIDARITY Report by David Bacon 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mexican Supermarkets & Grocery Stores Industry Report

Mexican Supermarkets & Grocery Stores Industry Report July 2018 Food Retail Report Mexico 2018Washington, D.C. Mexico City Monterrey Overview of the Mexican Food Retail Industry • The Mexican food retail industry consists in the distribution and sale of products to third parties; it also generates income from developing and leasing the real estate where its stores are located • Stores are ranked according to size (e.g. megamarkets, hypermarkets, supermarkets, clubs, warehouses, and other) • According to ANTAD (National Association of Food Retail and Department Stores by its Spanish acronym), there are 34 supermarket chains with 5,567 stores and 15 million sq. mts. of sales floor in Mexico • Estimates industry size (as of 2017) of MXN$872 billion • Industry is expected to grow 8% during 2018 with an expected investment of US$3.1 billion • ANTAD members approximately invested US$2.6 billion and created 418,187 jobs in 2017 • 7 states account for 50% of supermarket stores: Estado de Mexico, Nuevo Leon, Mexico City, Jalisco, Baja California, Sonora and Sinaloa • Key players in the industry include, Wal-Mart de Mexico, Soriana, Chedraui and La Comer. Other regional competitors include, Casa Ley, Merza, Calimax, Alsuper, HEB and others • Wal-Mart de México has 5.8 million of m² of sales floor, Soriana 4.3 m², Chedraui 1.2 m² and La Cómer 0.2 m² • Wal-Mart de México has a sales CAGR (2013-2017) of 8.73%, Soriana 9.98% and Chedraui 9.26% • Wal-Mart de México has a stores growth CAGR (2013-2017) of 3.30%, Soriana 5.75% and Chedraui 5.82% Number -

Grupo Comercial Chedraui, S.A.B. De C.V

GRUPO COMERCIAL CHEDRAUI, S.A.B. DE C.V. Av. Constituyentes No. 1150, Lomas Altas Delegación Miguel Hidalgo C.P. 11950 México, D. F. www.chedraui.com.mx Características de las acciones representativas del capital social de GRUPO COMERCIAL CHEDRAUI, S.A.B. DE C.V. Nominativas Sin valor nominal Íntegramente suscritas y pagadas Serie B Clase I Capital mínimo fijo sin derecho a retiro. Clave de Cotización en la Bolsa Mexicana de Valores, S.A.B. de C.V.: CHDRAUI Los valores emitidos por Grupo Comercial Chedraui, S.A.B. de C.V. se encuentran inscritos en el Registro Nacional de Valores y se cotizan en la Bolsa Mexicana de Valores, S.A.B. de C.V. La inscripción en el Registro Nacional de Valores no implica certificación sobre la bondad de los valores, la solvencia de la emisora o la exactitud o veracidad de la información contenida en el reporte anual, ni convalida los actos que, en su caso, se hubieren realizado en contravención de las leyes. Reporte anual que se presenta de acuerdo con las disposiciones de carácter general aplicables a las Emisoras de valores y a otros participantes del mercado, por el año terminado el 31 de diciembre de 2015. México, D.F. a 30 de abril de 2016 ÍNDICE 1. INFORMACIÓN GENERAL ........................................................................................... 4 a) Glosario de Términos y Definiciones ......................................................................... 4 b) Resumen Ejecutivo ................................................................................................. 6 c) Factores -

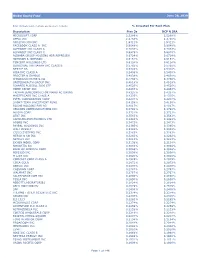

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA

Retirement Strategy Fund 2060 June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA ACTIVIA PROPERTIES INC REIT 0.0137% 0.0137% AEON REIT INVESTMENT CORP REIT 0.0195% 0.0195% ALEXANDER + BALDWIN INC REIT 0.0118% 0.0118% ALEXANDRIA REAL ESTATE EQUIT REIT USD.01 0.0585% 0.0585% ALLIANCEBERNSTEIN GOVT STIF SSC FUND 64BA AGIS 587 0.0329% 0.0329% ALLIED PROPERTIES REAL ESTAT REIT 0.0219% 0.0219% AMERICAN CAMPUS COMMUNITIES REIT USD.01 0.0277% 0.0277% AMERICAN HOMES 4 RENT A REIT USD.01 0.0396% 0.0396% AMERICOLD REALTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0427% 0.0427% ARMADA HOFFLER PROPERTIES IN REIT USD.01 0.0124% 0.0124% AROUNDTOWN SA COMMON STOCK EUR.01 0.0248% 0.0248% ASSURA PLC REIT GBP.1 0.0319% 0.0319% AUSTRALIAN DOLLAR 0.0061% 0.0061% AZRIELI GROUP LTD COMMON STOCK ILS.1 0.0101% 0.0101% BLUEROCK RESIDENTIAL GROWTH REIT USD.01 0.0102% 0.0102% BOSTON PROPERTIES INC REIT USD.01 0.0580% 0.0580% BRAZILIAN REAL 0.0000% 0.0000% BRIXMOR PROPERTY GROUP INC REIT USD.01 0.0418% 0.0418% CA IMMOBILIEN ANLAGEN AG COMMON STOCK 0.0191% 0.0191% CAMDEN PROPERTY TRUST REIT USD.01 0.0394% 0.0394% CANADIAN DOLLAR 0.0005% 0.0005% CAPITALAND COMMERCIAL TRUST REIT 0.0228% 0.0228% CIFI HOLDINGS GROUP CO LTD COMMON STOCK HKD.1 0.0105% 0.0105% CITY DEVELOPMENTS LTD COMMON STOCK 0.0129% 0.0129% CK ASSET HOLDINGS LTD COMMON STOCK HKD1.0 0.0378% 0.0378% COMFORIA RESIDENTIAL REIT IN REIT 0.0328% 0.0328% COUSINS PROPERTIES INC REIT USD1.0 0.0403% 0.0403% CUBESMART REIT USD.01 0.0359% 0.0359% DAIWA OFFICE INVESTMENT -

US-Mexico Trade Relationship

1 U.S. – Mexico Trade Relationship 2 Mexico is a growing economy Mexico has built a solid framework for macroeconomic stability in the past two decades Total Exports $374 billion $1.2 trillion economy $776 billion in total trade $457 billion in FDI attracted since 1999 125 million consumer market/ 60% middle class GDP 1.4% 2.3% 2.6% 2.3% 2013 2014 2015 2016 The 15th largest world economy 10th largest world exporter and 1st in Latin America 9th largest world importer 5th leading recipient of FDI Total Imports among emerging economies $387 billion Source: INEGI, SE-DGIE (Sep. 2016), WTO, UNCTAD, Brookings Institution, SHCP. 3 Recognizing the importance of NAFTA Trilateral trade has more than tripled, reaching nearly $1 trillion in 2016. Trilateral Trade between the NAFTA Partners 1,122 1200 1,075 1,059 1,033 1,010 997 942 1000 893 846 880 NAFTA 772 800 699 661 699 615 626 568 602 600 476 506 419 376 338 400 289 200 0 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Mexico-Canada Trade U.S.-Canada Trade Mexico-U.S. Trade Source: SE with import data from Statistics Canada, Banxico, and USDOC, and World Bank. 4 Since NAFTA, U.S.-Mexico trade has multiplied by six a million dollar a minute business Mexico is the U.S.’ third-largest trading partner $1.5 billion dollars in products are bilaterally traded each day U.S.-Mexico Trade 506 534 531 494 525 500 461 392 400 NAFTA 367 348 332 278 280 294 296 294 290 305 263 300 267 247 235 230 233 231 216 197 198 211 173 177 Billion 200 157 170 131 136 156 $ 131 134 138 108 82 101 110 226 86 95 240 236 231 100 198 217 74 163 50 62 134 137 152 129 40 111 102 111 120 71 79 87 97 97 42 51 46 57 0 199319941995199619971998199920002001200220032004200520062007200820092010201120122013201420152016 US Exports to Mexico US Imports from Mexico Source: USDOC. -

T E P N L R E V I E W

T e p n L R e v i e w , NUMBER 65 AUGUST 1998 SANTIAGO, CHILE OSCAR ALTIMIR Director o f the Review EUGENIO LAHERA Technical Secretary Notes and explanation of symbols The following symbols are used in tables in the Review: (...) Three dots indicate that data are not available or are not separately reported. (-) A dash indicates that the amount is nil or negligible. A blank space in a table means that the item in question is not applicable. (-) A minus sign indicates a deficit or decrease, unless otherwise specified. (■) A point is used to indicate decimals. (/) A slash indicates a crop year or fiscal year, e.g., 1970/1971. (-) Use of a hyphen between years, e.g., 1971-1973, indicates reference to the complete number of calendar years involved, including the beginning and end years. References to “tons” mean metric tons, and to “dollars”, United States dollars, unless otherwise stated. Unless otherwise stated, references to annual rates of growth or variation signify compound annual rates. Individual figures and percentages in tables do not necessarily add up to the corresponding totals, because of rounding. Guidelines for contributors to CEPAL Review The editorial board of the Review are always interested in encouraging the publication of articles which analyse the economic and social development of Latin America and the Caribbean. With this in mind, and in order to facilitate the presentation, consideration and publication of papers, they have prepared the following information and suggestions to serve as a guide to future contributors. —The submission of an article assumes an undertaking by the author not to submit it simultaneously to other periodical publications. -

Global Equity Fund Description Plan 3S DCP & JRA MICROSOFT CORP

Global Equity Fund June 30, 2020 Note: Numbers may not always add up due to rounding. % Invested For Each Plan Description Plan 3s DCP & JRA MICROSOFT CORP 2.5289% 2.5289% APPLE INC 2.4756% 2.4756% AMAZON COM INC 1.9411% 1.9411% FACEBOOK CLASS A INC 0.9048% 0.9048% ALPHABET INC CLASS A 0.7033% 0.7033% ALPHABET INC CLASS C 0.6978% 0.6978% ALIBABA GROUP HOLDING ADR REPRESEN 0.6724% 0.6724% JOHNSON & JOHNSON 0.6151% 0.6151% TENCENT HOLDINGS LTD 0.6124% 0.6124% BERKSHIRE HATHAWAY INC CLASS B 0.5765% 0.5765% NESTLE SA 0.5428% 0.5428% VISA INC CLASS A 0.5408% 0.5408% PROCTER & GAMBLE 0.4838% 0.4838% JPMORGAN CHASE & CO 0.4730% 0.4730% UNITEDHEALTH GROUP INC 0.4619% 0.4619% ISHARES RUSSELL 3000 ETF 0.4525% 0.4525% HOME DEPOT INC 0.4463% 0.4463% TAIWAN SEMICONDUCTOR MANUFACTURING 0.4337% 0.4337% MASTERCARD INC CLASS A 0.4325% 0.4325% INTEL CORPORATION CORP 0.4207% 0.4207% SHORT-TERM INVESTMENT FUND 0.4158% 0.4158% ROCHE HOLDING PAR AG 0.4017% 0.4017% VERIZON COMMUNICATIONS INC 0.3792% 0.3792% NVIDIA CORP 0.3721% 0.3721% AT&T INC 0.3583% 0.3583% SAMSUNG ELECTRONICS LTD 0.3483% 0.3483% ADOBE INC 0.3473% 0.3473% PAYPAL HOLDINGS INC 0.3395% 0.3395% WALT DISNEY 0.3342% 0.3342% CISCO SYSTEMS INC 0.3283% 0.3283% MERCK & CO INC 0.3242% 0.3242% NETFLIX INC 0.3213% 0.3213% EXXON MOBIL CORP 0.3138% 0.3138% NOVARTIS AG 0.3084% 0.3084% BANK OF AMERICA CORP 0.3046% 0.3046% PEPSICO INC 0.3036% 0.3036% PFIZER INC 0.3020% 0.3020% COMCAST CORP CLASS A 0.2929% 0.2929% COCA-COLA 0.2872% 0.2872% ABBVIE INC 0.2870% 0.2870% CHEVRON CORP 0.2767% 0.2767% WALMART INC 0.2767% -

TRADE MISSION Mexico City & Monterrey, Mexico June 11 - 16, 2017

IHA MEXICO TRADE MISSION Mexico City & Monterrey, Mexico June 11 - 16, 2017 ake part in an IHA/International Business Council (IBC) Trade Mission for a turn-key Tintroduction to an international market. Meetings, retail tours, receptions, transportation and hotel details are scheduled in advance, allowing you to focus on your business rather than the logistical details. Trade missions also allow for extensive networking with other industry participants who share common interests and goals. Join the IHA-IBC Trade Mission to meet buyers in Mexico City and Monterrey to increase international sales into the Mexican market. Through retailer and distributor meetings and retail tours, participants will receive a thorough understanding of this key market and obtain a personal network of key home and housewares retailers. SCHEDULE (SUBJECT TO CHANGE) Targeted retailers in Mexico City include: Saturday, June 10 ..........Arrive in Mexico City Amazon Mexico Sunday, June 11 .............Retail Tour Monday, June 12 ............One-on-one Retailer Meetings Casa Palacio / El Palacio de Hierro Tuesday, June 13 ...........One-on-one Retailer Meetings Wednesday, June 14 ......Fly to Monterrey The Home Store Wednesday, June 14 ......Retail Tour Idea Interior / Ideas Thursday, June 15 .........One-on-one Retailer Meetings Domésticas Friday, June 16 ..............One-on-one Retailer Meetings Liverpool Saturday, June 17 ..........Depart Monterrey Sears Tiendas Chedraui Targeted retailers in Monterrey include: Famsa HEB Mexico Home Depot Mexico Lowe’s Mexico Soriana “Participating in the IHA Trade Mission clearly enhanced our credibility with customers. It opened new doors for us and accelerated business development with existing customers. The ability to follow up in person with buyers who had visited us at the International Home + Housewares Show was invaluable. -

Grupo Financiero Banorte, S.A.B. De C.V

GRUPO FINANCIERO BANORTE, S.A.B. DE C.V. Monterrey, N.L., as of April 1, 2015. With respect to the First Notice published today, regarding the Annual General Shareholders’ Meeting to be held on April 24, 2015, shareholders are informed of the following for the Meeting´s agenda: ANNUAL GENERAL SHAREHOLDERS’ MEETING I.- Presentation and if the case, approval of the reports referred in section IV, Article 28 of the Securities Market Law, corresponding to the year ended December 31, 2014. First.- It is submitted to the Assembly’s consideration, with prior opinion by the Board of Directors, to approve the Chief Executive Officer’s Annual Report prepared according to Article 44, Section XI of the Securities Market Law, which contains among other things, the balance sheet, the income statement, the statement of changes in the stockholders’ equity and the statement of changes in the Company’s cash flow as of December 31, 2014.1 Second.- It is submitted to the Assembly’s consideration to approve the Board of Directors’ Annual Report, in which the main policies and accounting information and criteria are declared and explained, followed by the financial information as of December 31, 2014, in accordance with Article 172, paragraph b) of the “Ley General de Sociedades Mercantiles” (General Corporate’s Law). Third.- It is proposed to approve the Annual Report regarding operations and activities in which the Board of Directors was involved. Fourth.- It is proposed to approve the Annual Report regarding the activities of the Audit and Corporate Practices Committee. Fifth.- It is proposed to approve each and every one of the operations carried out by the Company during the year ended December 31, 2014 and to ratify the Minutes elaborated by the Board of Directors, the Chief Executive Officer and the Audit and Corporate Practices Committee during the same period. -

Grupo Financiero Banorte, S.A.B. De C.V

GRUPO FINANCIERO BANORTE, S.A.B. DE C.V. Monterrey, N.L., as of March 22nd, 2016. With respect to the First Notice published today calling to the Annual General Shareholders’ Meeting to be held on April 22nd, 2016, shareholders are informed of the following for the Meeting´s agenda: ANNUAL GENERAL SHAREHOLDERS’ MEETING I. Presentation and if the case, approval of the reports referred in section IV, Article 28 of the Securities Market Law, corresponding to the year ended December 31st, 2015. First.- It is submitted to the Assembly’s consideration, with prior opinion by the Board of Directors, to approve the Chief Executive Officer’s Annual Report prepared according to Article 44, Section XI of the Securities Market Law (Ley del Mercado de Valores) and Article 59, Section X of the Law Regulating Financial Groups (Ley para Regular las Agrupaciones Financieras), which contains among other things, the balance sheet, the income statement, the statement of changes in the stockholders’ equity and the statement of changes in the Company’s cash flow as of December 31st, 2015.1 Second.- It is submitted to the Assembly’s consideration to approve the Board of Directors’ Annual Report, in which the main policies and accounting information and criteria are declared and explained, followed by the financial information as of December 31st, 2015, in accordance with Article 172, paragraph b) of the General Corporate’s Law (Ley General de Sociedades Mercantiles). Third.- It is proposed to approve the Annual Report regarding operations and activities in which the Board of Directors was involved. Fourth.- It is proposed to approve the Annual Report regarding the activities of the Audit and Corporate Practices Committee. -

Report Name: Retail Foods

Required Report: Required - Public Distribution Date: July 01, 2021 Report Number: MX2021-0038 Report Name: Retail Foods Country: Mexico Post: Mexico City ATO Report Category: Retail Foods Prepared By: Fabiola Cortez Approved By: Gene Kim Report Highlights: In 2020, Mexico’s dynamic retail sector delivered a breakout year for retailer and consumer adoption of digital platforms in response to economic and public health challenges due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Retailers adapted to consumer preferences by pursuing an omnichannel marketing strategy serving customers at multiple Points of Sale and price points. Today Mexico's retailers offer integrated in-store and mobile app-based promotions, innovative store formats in convenient locations, and expanded offerings of versatile, value-oriented, and healthy product choices. According to U.S. Department of Agriculture data, Mexico is the United States’ second-largest export market for food and agricultural products following Canada. Due to an uneven economic recovery and an ongoing public health situation, market conditions remain uncertain in Mexico’s retail sector for the remainder of 2021. THIS REPORT CONTAINS ASSESSMENTS OF COMMODITY AND TRADE ISSUES MADE BY USDA STAFF AND NOT NECESSARILY STATEMENTS OF OFFICIAL U.S. GOVERNMENT POLICY Market Fact Sheet Mexico Executive Summary Quick Facts Mexico is the second-largest U.S. trading Imports of Consumer Products 2020 (INEGI): partner for goods and services. In 2020, U.S. $45.1 Billion exports of agricultural and related products to Mexico totaled $18.9 billion, a slight increase of Mexico´s most imported agriculture products (2019): 1.6 percent in comparison to 2019 despite 1. -

Mexico – the Year in Review

Mexico – The Year in Review President Enrique Peña Nieto, who had been so successful in advancing his fundamentally conservative economic program during his first year and a half in office, suddenly faced a serious challenge beginning in September 2014 when police apparently cooperating gangsters killed six students, injured at least 25 injured, and kidnapped 43 in the town of Iguala in the state of Guerrero. Protest demonstrations demanding that the students from the Ayotzinapa Rural Teachers College be returned alive, led by parents, students, and teachers quickly spread from Guerrero to Mexico City and around the nation. An international solidarity movement has also developed, with demonstrations at consulates in several countries. At about the same time, it was revealed that the president and his wife Angélica Rivera occupied a home that was owned by a major government contractor, while Secretary of Finance Luis Videgaray had similarly bought a home from a contractor. These revelations of conflict of interest at the highest levels of government, not so different from those portrayed in Luis Estrada’s new political satire film The Perfect Dictatorship, shocked even the jaded Mexican public. The exposé of wrong- doing at the top combined with large social movements from blow created a national political crisis that continued until the Christmas season led to a pause in the protests. The entire situation—the killings, the role of the police, and the corruption at the highest levels of government—has also created an international preoccupation with the Mexican situation. Economic Problems The economic and social crisis has been exacerbated by the country’s economic problems. -

Mexican Labor Year in Review: 2011

Mexican Labor Year in Review: 2011 https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article2452 Mexico Mexican Labor Year in Review: 2011 - Features - Publication date: Tuesday 24 January 2012 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/18 Mexican Labor Year in Review: 2011 Felipe Calderón's six-year term as president, which began to come to an end in 2011, represents one of the worst periods in modern Mexican history. The war on the drug cartels has taken 50,000 lives while failing to win a decisive victory against the cartels. The economy continues to experience very low growth while workers suffer unemployment or labor in the informal economy. The government's war on the workers continues unabated, with no resolution of the earlier attacks on electrical workers, miners, and airlines employees. The failure of Calderón and the National Action Party (PAN) to successfully resolve the country's most pressing problems while aggravating other issues has led to a decline of the PAN and the resurgence in recent years of the former ruling party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), known for its powerful political machine based on patronage and corruption. At the same time, despite the ferocious attacks on the electrical workers and miners, workers continue to fight for their unions, for their jobs and their contracts. Throughout the country activists protest against the drug war and army and police human rights violations. A new social movement, the Movement for Peace, Justice, and Dignity led by the poet Javier Sicilia, has challenged Calderón's drug policy, condemned the state's violence, and demanded justice for the indigenous and freedom for the country's political prisoners.