Mexico – the Year in Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Backgrounder April 2008

Center for Immigration Studies Backgrounder April 2008 “Jimmy Hoffa in a Dress” Union Boss’s Stranglehold on Mexican Education Creates Immigration Fallout By George W. Grayson Introduction During a five-day visit to the United States in February 2008, Mexican President Felipe Calderón lectured Washington on immigration reforms that should be accomplished. No doubt he will reprise this performance when he meets with President George W. Bush and Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper in New Orleans for the annual North American Leaders Summit on April 20-21, 2008. At a speech before the California State Legislature in Sacramento, the visiting head-of-state vowed that he was working to create jobs in Mexico and tighten border security. He conceded that illegal immigration costs Mexico “a great deal,” describing the immigrants leaving the country as “our bravest, our youngest, and our strongest people.” He insisted that Mexico was doing the United States a favor by sending its people abroad. “Americans benefit from immigration. The immigrants complement this economy; they do not displace workers; they have a strong work ethic; and they contribute in taxes more money than they receive in social benefits.”1 While wrong on the tax issue, he failed to address the immigrants’ low educational attainment. This constitutes not only a major barrier to assimilation should they seek to become American citizens, but also means that they have the wrong skills, at the wrong place, at the wrong time. Ours is not the economy of the nineteenth century, when we needed strong backs to slash through forests, plough fields, lay rails, and excavate mines. -

Looking at the 2006 Mexican Elections

CONFERENCE REPORT Looking at the 2006 Mexican Elections ELECTORAL DEMOCRACY AND POLITICAL Introduction PARTIES IN MEXICO On July 2, 2006, Mexicans will go to the polls to elect Mexico’s next president and to The widely accepted idea that more renew the federal Congress (senators and competitive electoral contests eventually deputies). The composition of Mexico’s new force a more institutionalized and open government will, no doubt, be of great nomination process of candidates was relevance for Canada, in light of the deep questioned by Prud’homme in light of the relationship that exists between these two developments observed in Mexico. Instead, countries as partners in North America. he argued, what we have seen in 2005 is that parties have met the requirement of Despite the importance of these elections, institutionalization and openness to different information about the electoral process and degrees. the developments in the political race to the presidency have not been covered Party of the Democratic Revolution (PRD) extensively in Canada. In the case of the PRD, the ideology of internal democracy seems to compete with For this reason, the Canadian Foundation for the preference to build unity around a leader the Americas (FOCAL) in partnership with capable of holding together the multiple the Centre for North American Politics and factions within the party. The selection of Society (CNAPS) at Carleton University Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) as convened the conference Looking at the 2006 the party’s candidate indicates the Mexican Elections to provide some insights continuation of their traditional model that about the nomination process of Mexico’s bases party unity on the existence of a main political parties, on the preferences of charismatic leader. -

+ Brh Dissertation Post-Defense Draft 2018-09-24 FINAL

In the Wake of Insurgency: Testimony and the Politics of Memory and Silence in Oaxaca by Bruno E. Renero-Hannan A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee Professor Ruth Behar, Co-Chair Associate Professor Sueann Caulfield, Co-Chair Professor Paul C. Johnson Professor Stuart Kirsch Professor Richard Turits, College of William and Mary Bruno E. Renero-Hannan [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-1529-7946 © Bruno E. Renero-Hannan 2018 Para Elena, Louisa, y Amelia Y para Elvira ii Acknowledgements It takes a village, and I have gained many debts in the elaboration of this dissertation. At every step of the way I have benefited from guidance and support of family, friends, colleagues, teachers, and compas. To begin with, I would like to thank my advisors and the co-chairs of my dissertation committee. Ruth Behar helped me find the voices I was looking for, and a path. I am grateful for her generosity as a reader, story-listener, and mentor, as well as her example as a radical practitioner of ethnography and a gifted writer. I came to know Sueann Caulfield as an inspiring teacher of Latin American history, whose example of commitment to teaching and research I carry with me; as co-chair, she guided me through multiple drafts of this work, offering patient encouragement and shrewd feedback, and motivating me to complete it. Stuart Kirsch was a supportive advisor throughout my early years at Michigan and fieldwork, introducing me to social movement studies and helping to shape the focus of my research. -

A Guide to the Leadership Elections of the Institutional Revolutionary

A Guide to the Leadership Elections of the Institutional Revolutionary Party, the National Action Party, and the Democratic Revolutionary Party George W. Grayson February 19, 2002 CSIS AMERICAS PROGRAM Policy Papers on the Americas A GUIDE TO THE LEADERSHIP ELECTIONS OF THE PRI, PAN, & PRD George W. Grayson Policy Papers on the Americas Volume XIII, Study 3 February 19, 2002 CSIS Americas Program About CSIS For four decades, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has been dedicated to providing world leaders with strategic insights on—and policy solutions to—current and emerging global issues. CSIS is led by John J. Hamre, formerly deputy secretary of defense, who has been president and CEO since April 2000. It is guided by a board of trustees chaired by former senator Sam Nunn and consisting of prominent individuals from both the public and private sectors. The CSIS staff of 190 researchers and support staff focus primarily on three subject areas. First, CSIS addresses the full spectrum of new challenges to national and international security. Second, it maintains resident experts on all of the world’s major geographical regions. Third, it is committed to helping to develop new methods of governance for the global age; to this end, CSIS has programs on technology and public policy, international trade and finance, and energy. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., CSIS is private, bipartisan, and tax-exempt. CSIS does not take specific policy positions; accordingly, all views expressed herein should be understood to be solely those of the author. © 2002 by the Center for Strategic and International Studies. -

Ex-President Carlos Salinas De Gortari Rumored to Return to Mexican Politics LADB Staff

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository SourceMex Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) 7-23-2003 Ex-President Carlos Salinas de Gortari Rumored to Return to Mexican Politics LADB Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sourcemex Recommended Citation LADB Staff. "Ex-President Carlos Salinas de Gortari Rumored to Return to Mexican Politics." (2003). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/sourcemex/4658 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Latin America Digital Beat (LADB) at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in SourceMex by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LADB Article Id: 52662 ISSN: 1054-8890 Ex-President Carlos Salinas de Gortari Rumored to Return to Mexican Politics by LADB Staff Category/Department: Mexico Published: 2003-07-23 Former President Carlos Salinas de Gortari (1988-1994) has reappeared as an influential figure in the Mexican political scene. Reports surfaced after the 2003 mid-term elections that the former president had played a major behind-the-scenes role in the campaigns of several of his fellow members of the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI), although no one could offer any concrete proof that the president actually participated in electoral activities. With or without Salinas' help, the PRI won four gubernatorial races and a plurality of seats in the congressional election, leaving the party in a strong position to dictate the agenda in the Chamber of Deputies during the 2003-2006 session (see SourceMex, 2003-07-09). Still, Salinas' return to prominence marks a major turnaround from the mid-1990s, when the president went into self-imposed exile to Ireland and Cuba after taking the blame for the 1994 peso devaluation and the ensuing economic crisis. -

The Resilience of Mexico's

Mexico’s PRI: The Resilience of an Authoritarian Successor Party and Its Consequences for Democracy Gustavo A. Flores-Macías Forthcoming in James Loxton and Scott Mainwaring (eds.) Life after Dictatorship: Authoritarian Successor Parties Worldwide, New York: Cambridge University Press. Between 1929 and 2000, Mexico was an authoritarian regime. During this time, elections were held regularly, but because of fraud, coercion, and the massive abuse of state resources, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) won virtually every election. By 2000, however, the regime came to an end when the PRI lost the presidency. Mexico became a democracy, and the PRI made the transition from authoritarian ruling party to authoritarian successor party. Yet the PRI did not disappear. It continued to be the largest party in Congress and in the states, and it was voted back into the presidency in 2012. This electoral performance has made the PRI one of the world’s most resilient authoritarian successor parties. What explains its resilience? I argue that three main factors explain the PRI’s resilience in the aftermath of the transition: 1) the PRI’s control over government resources at the subnational level, 2) the post-2000 democratic governments’ failure to dismantle key institutions inherited from the authoritarian regime, and 3) voters’ dissatisfaction with the mediocre performance of the PRI’s competitors. I also suggest that the PRI's resilience has been harmful in various ways, including by propping up pockets of subnational authoritarianism, perpetuating corrupt practices, and undermining freedom of the press and human rights. 1 Between 1929 and 2000, Mexico was an authoritarian regime.1 During this time, elections were held regularly, but because of fraud, coercion, and the massive abuse of state resources, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) won virtually every election. -

Doing Business in Mexico Doing Business in Mexico

Issue: Doing Business in Mexico Doing Business in Mexico By: Christina Hoag Pub. Date: September 14, 2015 Access Date: October 1, 2021 DOI: 10.1177/2374556815608835 Source URL: http://businessresearcher.sagepub.com/sbr-1645-96878-2693503/20150914/doing-business-in-mexico ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. ©2021 SAGE Publishing, Inc. All Rights Reserved. Is the climate welcoming for international companies? Executive Summary Seeking to improve its economy and the standard of living for its 122 million citizens, Mexico is undergoing a massive transformation as it courts foreign investors and an array of trade partners. It has embarked on an ambitious agenda of domestic reforms—opening the oil sector to private investors for the first time in 76 years, breaking up telecommunications monopolies and modernizing education, as well as overhauling outdated infrastructure and cultivating a portfolio of free-trade agreements. The result has been a boom in trade and investment in the world's 11th largest economy. But the country faces notable challenges, chiefly high rates of violent crime, endemic corruption, a wide gap in wealth distribution and an underskilled workforce. Experts say Mexico's potential as an economic powerhouse will continue to go unfulfilled unless those pressing social issues can be reined in. Among the questions of concern for international business: Is labor cost-effective in Mexico? Is it safe to operate there? Does Mexico offer investors sufficient and reliable infrastructure? Overview March 18, 1938, is a proud date in Mexican history, memorized by generations of schoolchildren along with the dates of the country's independence from Spanish and French rule. -

The Snte, Elba Esther Gordillo and the Administration of Calderón Carlos Ornelas

THEMATIC ESSAY THE SNTE, ELBA ESTHER GORDILLO AND THE ADMINISTRATION OF CALDERÓN CARLOS ORNELAS Carlos Ornelas is a professor in the department of education and communication at Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana, Xochimilco campus. Calzada del Hueso 1100, Colonia Villa Quietud, CP 04960. E-MAIL: [email protected] Abstract: Although the National Union of Workers in Education (Sindicato Nacional de Trabajadores de la Educación–SNTE) no longer has the monopoly of representing the teaching profession, and in spite of movements that challenge the leadership of the group’s president, the group continues to be the most powerful union organization in Mexico. Its power extends to other areas of political life, bureaucratic institutions, and to an even greater degree, to the administration of basic education. One might believe that the SNTE and its president, Elba Esther Gordillo, have become more powerful under the protection of President Felipe Calderón, yet they face new challenges. This article analyzes the corporatist practices of the SNTE and the institutional consequences for the Secretariat of Public Education, especially in terms of the behaviors of the bureaucratic cadres. During the analysis, theoretical notions for explaining the case are discussed. Key words: basic education, power, unionism, educational policy, Mexico. Reason cannot become transparent to itself as long as men act as members of an organization that lacks reason.1 (Horkheimer, 1976:219) Introduction Many analysts believed that the wave of neoliberal economic reforms that appeared in Latin America in the 1980s would reduce the power of the unions, whose influence had grown through state expansion, economic protectionism, a rigid labor market, and political protection (Murillo, 2001). -

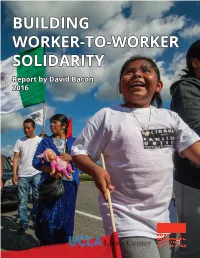

BUILDING WORKER-TO-WORKER SOLIDARITY Report by David Bacon 2016

BUILDING WORKER-TO-WORKER SOLIDARITY Report by David Bacon 2016 1 Table of Contents BUILDING WORKER-TO-WORKER SOLIDARITY Report by David Bacon Introduction..........................................................................................................................................................................1 Defending Miners in Cananea and Residents of the Towns Along the Rio Sonora.....................................................2 Facing Bullets and Prison, Mexican Teachers Stand Up to Education Reforms.........................................................7 Farm Workers Are in Motion from Washington State to Baja California...................................................................11 El Super Workers Fight for Justice in Stores in Both Mexico and the U.S....................................................................16 The CFO Promotes Cross-Border Links to Build Solidarity and Understand Globalization from the Bottom Up..18 Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung—New York Office Address: 275 Madison Avenue, Suite 2114, New York, NY 10016; www.rosalux- nyc.org Institute for Transnational Social Change (ITSC) at the UCLA Labor Center Address: Ueberroth Building, 10945 Le Conte Ave, Los Angeles, CA 90024 New York and Los Angeles, September 2016 INTRODUCTION learn about the truly remarkable campaigns undertaken by workers at the local level facing global companies, but also to highlight the fact that international workers alliances can As part of the UCLA Labor Center’s Global Soli- play a key role in their support. The report describes and darity project, the Institute for Transnational Social Change analyzes the political and economic context in which these (ITSC) provides academic resources and a unique strate- struggles are taking place, and contains as well the analysis gic space for discussion to transnational leaders and their of the Comité Fronterizo de Obreras of the importance of organizations involved in cross-border labor, worker and cross border solidarity and its relation to labor rights under immigrant rights action. -

Pena Nieto Declared President

DePaul Journal for Social Justice Volume 6 Issue 2 Spring 2013 Article 5 January 2016 Pena Nieto Declared President Tom Hansen Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jsj Recommended Citation Tom Hansen, Pena Nieto Declared President, 6 DePaul J. for Soc. Just. 209 (2013) Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/jsj/vol6/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in DePaul Journal for Social Justice by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hansen: Pena Nieto Declared President PENA NIETO DECLARED PRESIDENT BY TOM HANSEN' MEXICO SOLIDARITY NETWORK To no one's surprise, but to the dismay of much of the coun- try, the Federal Electoral Institute ("IFE") unanimously anointed the Institutional Revolutionary Party ("PRI") candi- date Enrique Pena Nieto as the next President of Mexico on September 7, 2012 at a press conference. The IFE managed to overlook millions of dollars in vote-buying, illegal campaign spending, and PRI's coordination with Televisa, a multi-media mass media company part of Mexico's television duopoly that controls most programming in the country, which guaranteed a PRI return to power after twelve years of PAN presidencies. Runner-up Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador and the PRD fought a losing battle to overturn yet another corrupt presidential elec- tions. Pena Nieto will don the presidential sash on December 1, 2012 in a formal ceremony that promises to draw massive pro- tests from students and workers. -

Mexican Labor Year in Review: 2011

Mexican Labor Year in Review: 2011 https://internationalviewpoint.org/spip.php?article2452 Mexico Mexican Labor Year in Review: 2011 - Features - Publication date: Tuesday 24 January 2012 Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine - All rights reserved Copyright © International Viewpoint - online socialist magazine Page 1/18 Mexican Labor Year in Review: 2011 Felipe Calderón's six-year term as president, which began to come to an end in 2011, represents one of the worst periods in modern Mexican history. The war on the drug cartels has taken 50,000 lives while failing to win a decisive victory against the cartels. The economy continues to experience very low growth while workers suffer unemployment or labor in the informal economy. The government's war on the workers continues unabated, with no resolution of the earlier attacks on electrical workers, miners, and airlines employees. The failure of Calderón and the National Action Party (PAN) to successfully resolve the country's most pressing problems while aggravating other issues has led to a decline of the PAN and the resurgence in recent years of the former ruling party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), known for its powerful political machine based on patronage and corruption. At the same time, despite the ferocious attacks on the electrical workers and miners, workers continue to fight for their unions, for their jobs and their contracts. Throughout the country activists protest against the drug war and army and police human rights violations. A new social movement, the Movement for Peace, Justice, and Dignity led by the poet Javier Sicilia, has challenged Calderón's drug policy, condemned the state's violence, and demanded justice for the indigenous and freedom for the country's political prisoners. -

Union-Party Links and the Reconfiguration of the Labor Movement: Brazil and Mexico 1990-2007 by Andra Olivia Miljanic a Disserta

Union-Party Links and the Reconfiguration of the Labor Movement: Brazil and Mexico 1990-2007 by Andra Olivia Miljanic A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor David Collier, Co-chair Professor Ruth Berins Collier, Co-chair Professor Laura Stoker Professor J. Nicholas Ziegler Professor Harley Shaiken Fall 2010 © Copyright by Andra Olivia Miljanic 2010 All Rights Reserved Abstract Union-Party Links and the Reconfiguration of the Labor Movement: Brazil and Mexico 1990-2007 by Andra Olivia Miljanic Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science University of California, Berkeley Professor David Collier and Professor Ruth Berins Collier, Co-chairs This study examines the reconfiguration of labor movements in Latin America, focusing on the automotive sector in Brazil and Mexico and comparing the two countries across two crucial decades—the 1990s and the 2000s. The analysis situates this reconfiguration in a crucial historical context. Thus, the transitions to democracy and open-market economies that began in most Latin American countries in the 1980s prompted a restructuring of relations within the labor movements, connected with changing relations among labor, state, and business actors. The automotive industry, a pillar of the Brazilian and Mexican economies, experienced a similar economic transition and pattern of foreign direct investment across the two countries. However, over the last two decades, cooperation among auto worker unions—which historically have been among the most important labor actors in these countries—has evolved in opposite directions.