Environment and Land Use in the Lower Lea Valley C. 12500 BC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Middlesex University Research Repository an Open Access Repository Of

Middlesex University Research Repository An open access repository of Middlesex University research http://eprints.mdx.ac.uk Read, Simon ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2380-5130 (2017) Cinderella River: The evolving narrative of the River Lee. http://hydrocitizenship.com, London, pp. 1-163. [Book] Published version (with publisher’s formatting) This version is available at: https://eprints.mdx.ac.uk/23299/ Copyright: Middlesex University Research Repository makes the University’s research available electronically. Copyright and moral rights to this work are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners unless otherwise stated. The work is supplied on the understanding that any use for commercial gain is strictly forbidden. A copy may be downloaded for personal, non-commercial, research or study without prior permission and without charge. Works, including theses and research projects, may not be reproduced in any format or medium, or extensive quotations taken from them, or their content changed in any way, without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). They may not be sold or exploited commercially in any format or medium without the prior written permission of the copyright holder(s). Full bibliographic details must be given when referring to, or quoting from full items including the author’s name, the title of the work, publication details where relevant (place, publisher, date), pag- ination, and for theses or dissertations the awarding institution, the degree type awarded, and the date of the award. If you believe that any material held in the repository infringes copyright law, please contact the Repository Team at Middlesex University via the following email address: [email protected] The item will be removed from the repository while any claim is being investigated. -

Invest in Three Waters Bow Creek, E3

INVEST IN THREE WATERS BOW CREEK, E3. % 4PREDICTED RENT GROWTH IN LONDON THIS YEAR.1 1 Independent, 2019 INVESTOR CONFIDENCE HEADS EAST Buoyed by price growth, rental yield and government and business confidence, East London regeneration is at the heart of London’s fastest growing area.1 STRATFORD Over half of the Capital’s population now lives east of £800 /SQ FT* Tower Bridge. Hackney The region has become a beacon for City workers, creatives and entrepreneurs, all demanding SHOREDITCH competitively-priced homes with rapid journey times. Bow £1,325 This makes for strong capital growth prospects and /SQ FT* LONDON E3 gives confidence to buy-to-let investors, as these Bethnal Green CREEK BOW professionals demand high quality rental properties. ~ PROJECTED PRICE GROWTH2 LONDON Stepney House price performance in the Lower Lea Valley compared. Indexed 100 = September 2008. ~ E3 180 LOWER LEA VALLEY WHITECHAPEL NEWHAM The City £738 160 /SQ FT* TOWER HAMLETS £950 Poplar 140 /SQ FT* Shadwell 120 100 St Katharine & Wapping 2011 2017 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2010 2018 2009 2008 CANARY WHARF Borough 2 £1,250 PROJECTED POPULATION GROWTH 2018 – 2028 /SQ FT* Rotherhithe East London’s boroughs are catching the wave of population and demand growth that helps cement price growth. TOWER NEWHAM HACKNEY KENSINGTON CITY OF HAMLETS AND CHELSEA LONDON 12.8% 11.3% 10.6 % 4.5 % 2.7% 3 1 Dataloft Land Registry increase in Inner London regeneration developments 2012–2016 * Based on average property prices 2 Knight Frank Research / GLA INVESTOR CONFIDENCE HEADS EAST Buoyed by price growth, rental yield and government and business confidence, East London regeneration is at the heart of London’s fastest growing area.1 STRATFORD Over half of the Capital’s population now lives east of £8,610 /SQ M* Tower Bridge. -

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD

LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 1 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD ACC/2423 Reference Description Dates LEE CONSERVANCY BOARD ENGINEER'S OFFICE Engineers' reports and letter books LEE CONSERVANCY BOARD: ENGINEER'S REPORTS ACC/2423/001 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1881 Jan-1883 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/002 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1884 Jan-1886 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/003 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1887 Jan-1889 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/004 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1890 Jan-1893 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/005 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1894 Jan-1896 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/006 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1897 Jan-1899 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/007 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1903 Jan-1903 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/008 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1904 Jan-1904 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/009 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1905 Jan-1905 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/010 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1906 Jan-1906 Lea navigation Dec 1 volume LONDON METROPOLITAN ARCHIVES Page 2 BRITISH WATERWAYS BOARD ACC/2423 Reference Description Dates ACC/2423/011 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1908 Jan-1908 Lea navigation/ stort navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/012 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1912 Jan-1912 Lea navigation/ stort navigation Dec 1 volume ACC/2423/013 Reports on navigation - signed copies 1913 Jan-1913 Lea navigation/ stort navigation -

Society CONTENTS

________________________ society NEWS The Bulletin of the ENFIELD ARCHAEOLOGICAL SOCIETY ________________________ December 2001 No 163 CONTENTS FORTHCOMING EVENTS EAS MEETINGS 14 December 2001: Poland: 1000 Years of ivilisation 1" Jan$ary 2002: PP%16 & ommercial 'rchaeolo)y, +as it Worked- 1. /ebr$ary 2002: rimea: 0eltin) Pot of Peo1le OTHER SOCIETIES SOCIETY MATTERS MEETING REPORTS York 0inster: En)land2s 3ar)est Stained %lass 0$se$m 4ensal %reen emetery THE OUTPUT FROM THE WHITEWEBBS PUMPIMG STATION AND THE SECTION OF THE NEW RIVER LOOP IN THE GROUNDS OF MYDDELTON HOUSE ENFIELD PASTFINDERS: NEWS FROM THE FIELDWORK GROUP OBITUARY: PETER REYNOLDS INNOVA PARK, RAMMEY MARSH SMALL FINDS Society Ne5s is 1$blished 6$arterly in 0arch* #$ne* Se1tember and December 7(e Editor is Jon 7anner* 24 Padsto5 8oad* Enfeld* 0iddlese: EN2 ";<* tel: 020 "36= "000 >day)@ 020 "3.0 04A3 >(ome?@ email: BmtCb(11DcoD$4 2 develo1ers and t(e a$t(orities 5ill be e:1lored FORTHCOMING to attem1t to determine 5(et(er commercial archaeolo)y (as 5orkedD /inally, t(e matter of EVENTS local versus commercial archaeolo)y 5ill be e:amined N do 5e need chan)e- Jon 'anner()obin *ensem 0eetin)s of t(e Enfeld 'rc(aeolo)ical Society are (eld at #$bilee +all* 2 Parsona)e 3ane* Friday 1+ F!$ruary %&&% Enfeld >near (ase Side? at "D001mD 7ea and Crimea: +elting Pot of People coEee are served and t(e sales and information Ian Jones table is o1en from =D301mD Fisitors, for 5(om a c(ar)e of G1D00 5ill be made* are very 5elcomeD 7(ere is far more to t(e rimean 1enins$lar on t(e nort( -

Lee Valley Regional Park Strategic Planning Evidence and Policies

Lee Valley Regional Park Authority Park Development Framework Strategic Policies April 2019 Lee Valley Regional Park Authority Park Development Framework Strategic Policies Prepared by LUC Planning & EIA LUC LONDON Offices also in: Land Use Consultants Ltd Design 43 Chalton Street Bristol Registered in England Registered number: 2549296 Landscape Planning London Edinburgh Registered Office: Landscape Management NW1 1JD Glasgow 43 Chalton Street Ecology T +44 (0)20 7383 5784 Lancaster London NW1 1JD GIS & Visualisation [email protected] Manchester FS 566056 EMS 566057 LUC uses 100% recycled paper Executive Summary Extending north from East India Dock Basin for 26 miles, and broadly aligned with the natural course of the river Lea through east London and Essex to Ware in Hertfordshire, the Lee Valley Regional Park presents a rich tapestry of award winning international sports venues, attractive parklands and areas of significant ecological importance. The Park attracts over 7 million visits each year largely drawn from London, Hertfordshire and Essex but given the international status of its venues increasingly from across the United Kingdom and abroad. The Regional Park lies at the centre of one of Europe’s largest regeneration areas which includes London 2012 and its Legacy, major developments in the lower Lee Valley, Meridian Water and a range of large schemes coming forward in Epping Forest District and the Borough of Broxbourne. The Authority’s adopted policies date from 2000 and, given the Regional Park’s rapidly changing context, a new approach is required. The Strategic Aims and Policies, Landscape Strategy and Area Proposals included in the Park Development Framework are designed to respond to this changing context to ensure that the Regional Park can maintain its role as an exciting and dynamic destination which caters for leisure, recreation and the natural environment over the next 10-15 years. -

London's Olympic Preparations and Housing Rights Concerns

HOSTING THE 2012 OLYMPIC GAMES: LONDON’S OLYMPIC PREPARATIONS AND HOUSING RIGHTS CONCERNS Background Paper COHRE’s Mega-Events, Olympic Games and Housing Rights Project is supported by the Geneva International Academic Network (GIAN) 2007 © COHRE, 2007 Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions Rue de Montbrillant 83 1202 Geneva Switzerland Tel: +41.22.734.1028 Fax: +41.22.733.8336 Email: [email protected] http://www.cohre.org Prepared by Claire Mahon Background This background research paper is part of the COHRE Mega-Events, Olympic Games and Housing Rights Project. It was prepared as a preliminary independent study of the impact of the London Olympics on housing rights. Similar studies were done for the cities of Atlanta, Athens, Barcelona, Beijing, London, Seoul and Sydney. The background research papers were used in the preparation of COHRE’s Fair Play for Housing Rights: Mega-Events, Olympic Games and Housing Rights report, launched in Geneva on 5 June 2007. The contents and opinions of the material available in this paper are those of the author and do not necessarily correspond with those of COHRE. All documents published as part of this project are available at: www.cohre.org/mega-events/. Acknowledgements This project was funded by the Geneva International Academic Network (GIAN). Research assistance for part II of this report was provided by Nicholas Jaquier. Many thanks to the local residents and housing activists who provided valuable input and advice on this study. Publications in the COHRE Mega-Events, Olympic Games and Housing -

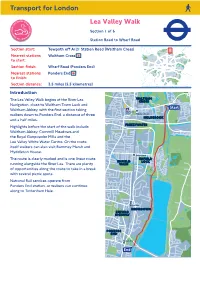

Lea-Valley-Section-1.Pdf

Transport for London.. Lea Valley Walk. Section 1 of 6. Station Road to Wharf Road. Section start: Towpath off A121 Station Road (Waltham Cross). Nearest stations Waltham Cross . to start: Section finish: Wharf Road (Ponders End). Nearest stations Ponders End . to finish: Section distance: 3.5 miles (5.5 kilometres). Introduction. The Lea Valley Walk begins at the River Lea Navigation, close to Waltham Town Lock and Waltham Abbey, with the first section taking walkers down to Ponders End, a distance of three and a half miles. Highlights before the start of the walk include Waltham Abbey, Cornmill Meadows and the Royal Gunpowder Mills and the Lee Valley White Water Centre. On the route itself walkers can also visit Rammey Marsh and Myddleton House. The route is clearly marked and is one linear route running alongside the River Lea. There are plenty of opportunities along the route to take in a break with several picnic spots. National Rail services operate from Ponders End station, or walkers can continue along to Tottenham Hale. Continues on next page Directions. From Waltham Cross station turn right out of the station, up the steps and right onto Eleanor Cross Road. After half a mile - on your left - you pass the entrance to the new Lee Valley White Water Centre (built for the London 2012 Olympics). Continue on the main road and shortly after the traffic lights turn right onto the towpath which can be found just before Station Road becomes Highbridge Street. To reach the town of Waltham Abbey continue along Highbridge Street. Here you can visit Waltham Abbey church (approximately 10 minutes walk away), Cornmill Meadows and the Royal Gunpowder Mills. -

Lee Valley Regional Park Landscape Character Assessment

LCT C: Urban Valley Floor with Marshlands SPA, which provides a nationally important habitat for overwintering birds. Cultural Influences 4.64 The low-lying land of rich alluvial deposits supported a system of grazing, referred to as the Lammas system5 from the Anglo-Saxon period to the end of the C19th. Grazing rights on the marshes were extinguished by the early C20th and a substantial proportion of the marshlands, with the exception of Walthamstow Marshes, were then modified by industrial activities and landfill, including the dumping of bomb rubble after WW2. In the 1950 and 60s the construction of flood relief channels ended the periodic inundation of the marshlands. 4.65 Communication routes through the valley floor proliferated over the C20th, including pylons, roads and railway lines mounted on embankments, but residential and industrial development remains largely confined to the margins. 4.66 Public access and recreation now characterises much of the marshlands, with some areas managed as nature reserves. However substantial infrastructure, such as the railway lines and flood relief channels and adjacent industrial development, means access through and into the marshes from surrounding urban areas is often severed. The tow-path following the River Lee Navigation provides a continuous link along the valley for visitors to enjoy the landscape. 5 A system of grazing whereby cattle was grazed only after the cutting and collection of hay Lee Valley Regional Park Landscape Strategy 85 April 2019 LCA C1: Rammey Marsh Lee Valley Regional Park Landscape Strategy 86 April 2019 LCA C1: Rammey Marsh Occasional long views out to wooded valley sides between Residential properties overlooking the southern area across the riverside vegetation. -

LEA RIVER PARK PRIMER © Philip Vile LEA RIVER PARK PRIMER

LEA RIVER PARK PRIMER © Philip Vile LEA RIVER PARK PRIMER CONTENTS Welcome to the Park 4 Executive Summary 6 Introduction 8 Completing the Lee Valley Park 10 An Amazing Valley 12 The Context of the Lea Valley 14 The Six Parks and the Leaway 16 A Day Out in the Lea River Park 18 Curating the Valley 20 The Leaway 22 The Leaway - Overcoming Severance 24 Twelvetrees Crescent 26 Poplar Reach and Cody Dock 28 Canning Town Connections 30 Exotic Wild 32 Silvertown Viaduct 36 Future Phased Delivery 38 Conclusion 40 Published October 2016 WELCOME TO THE PARK The Lea River Park provides an exciting opportunity to invest in Newham’s wealth of natural resources in waterways and green spaces, in addition to the industrial and built heritage, to create an outstanding public space accessible to all who live and work in the borough. Our vision for the Lea River Park is for high quality, accessible parkland incorporating open space and waterways with new walking and cycling routes which will add to the decades of investment in transport infrastructure that have gone into the borough, enabling our community to be even better connected. Running through the spine of the borough’s key opportunity area, the park and improved connections will help to attract further investment into the borough whilst providing high quality leisure and recreational space to those who live and work here. With the scale of regeneration taking place in Newham, it makes us one of the most exciting places to visit in the UK. Sir Robin Wales Mayor of Newham Everybody recognises the Thames as the lifeblood of London. -

Download Full Publication

centreforcities discussion paper no. 8 December 2006 setting the bar preparing for London’s Olympic legacy Tracy Kornblatt Abstract focus on the longer term regeneration opportunities in East London, and match people to Olympics jobs where possible. A year after winning the bid, London is gearing up to deliver 3. Marginal benefits outside London: Other regions of the the London 2012 Olympic Games. The Games plan promises to UK should manage down their expectations for 2012 and regenerate the East London site and its surroundings. This avoid competing for small slivers of Olympics cash. paper assesses the likely economic impact of the Games on East 4. Focus on the soft stuff: The indirect, ‘soft’ impacts, includ- London, Greater London and the UK. ing accelerated infrastructure investment, are likely to be We need to be realistic about what the Games can deliver. substantial and lasting. Games planners should focus on Not all local residents will be able to access the employment these indirect benefits to maximise the Games’ legacy. opportunities created by the Games. And areas outside of 5. Be clear about costs: Current uncertainty over the final London will not all gain as much as they anticipate. To avoid costs threatens to undermine the goodwill behind the disappointment later, we should all adjust our expectations Games. The final distribution of costs should be clarified as now. soon as possible to allow forward planning for other proj- A substantial, lasting London 2012 legacy is within reach. ects across the UK. But London needs to make sure that the potential gains are realised. -

Looking Forward to the Next Ten Years

Looking forward to the next ten years London Waterway Partnership Ten Year Strategic Plan 2014 1 Welcome I am delighted to present the London Waterway Partnership’s Strategic Plan. Preparation of the plan has taken a good deal of the Partnership’s early effort, but we have been much helped by the reception and comments arising from our draft document and the two consultation meetings held in December 2013. We are also grateful for the written comments received from the Heritage Lottery Fund; the Hillingdon Canal Partnership; London Boaters and Mark Walton, the River Lee Tidal Mill Trust and Westminster City Council. The document has been strengthened by the valuable points made by our respondents, particularly in emphasising the way in which London waterways can enrich regeneration opportunities and support education, training and volunteering. Our strategy is not set in stone. It is designed to develop over time with the continuing input from those supporting our waterways. We will report progress at our Annual Meeting. Our aspirations are ambitious and how quickly the objectives are met, will depend on the resources available in terms of money and support from within the Canal & River Trust and externally. What is not in question is our conviction that the regional and local elements of the Trust’s overall strategy should be emphasised. We set up the Partnership Board of 12 members in July 2013 and deliberately chose to make the board as diverse as possible in order to reflect the very wide range of interests in canals and waterways. I have been impressed by the Board’s commitment and enthusiasm, characteristics which have been reflected in the many people we have met in getting to know the key elements of London’s very diverse waterways. -

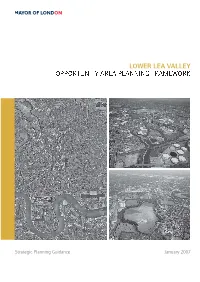

Lower Lea Valley Planning Framework

LOWER LEA VALLEY Strategic Planning Guidance January 2007 II | OPPORTUNITY AREA PLANNING FRAMEWORK Copyright: Greater London Authority and London Development Agency January 2007 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries: 020 7983 4100 minicom: 020 7983 4458 ISBN 978 1 85261 988 6 Photographs: Cover: LDA Foreword: Liane Harris Maps based on Ordnance Survey Material. Crown Copyright. License No. LA100032379 Acknowledgements The Framework was prepared by the Greater London Authority with the support of a consortium led by EDAW plc with Allies & Morrison, Buro Happold, Capita Symonds, Halcrow and Mace and with additional support from Faithful & Gould, Hunt Dobson Stringer, Jones Lang LaSalle and Witherford Watson Mann Architects. LOWER LEA VALLEY OPPORTUNITY AREA PLANNING FRAMEWORK | i FOREWORD I am delighted to introduce the Opportunity Area Planning Framework for the Lower Lea Valley. The Framework sets out my vision for the Valley, how it could change over the next decade, and what that change would mean for residents, businesses, landowners, public authorities and other stakeholders. It builds on the strategic planning policies set out in my 2004 London Plan for an area of nearly 1450 hectares, extending from the Thames in the south to Leyton in the north, straddling the borders of Newham, Tower Hamlets, Hackney and Waltham Forest. The Lower Lea Valley is currently characterised by large areas of derelict industrial land and poor housing. Much of the land is fragmented, polluted and divided by waterways, overhead pylons, roads and railways. My aim is to build on the area’s unique network of waterways and islands to attract new investment and opportunities, and to transform the Valley into a new sustainable, mixed use city district, fully integrated into London’s existing urban fabric.