Navajo Sandpainting Textiles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wool Characteristics in Relation to Navajo Weaving

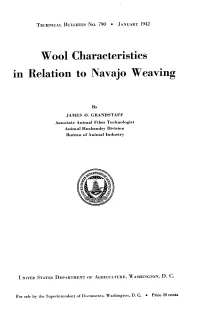

TECHNICAL BULLETIN NO. 790 • JANUARY 1942 Wool Characteristics in Relation to Navajo Weaving By JAMES O. GRANDSTAFF Associate Animal Fiber Technologist Animal Husbandry Division Bureau of Animal Industry LNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF AGRICULTURE, WASHINGTON, D. C. For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. G. • Price 20 cents Technical Bulletin No. 790 • January 1942 llgFA|i:tBlEIV*r «F ACSIIIC1JI.TI7RE WASIIIM«T»N, »* C. Wool Characteristics in Relation to Navajo Weaving' By JAMES O. GBANDSTAPF ^ Associate animal fiber technologist, Animal Husbandry Division, Bureau of Animal Industry CONTENTS Page Page Introduction 1 Experimental results 12 Purpose of study 7 Rugs woven from wool of experimental Materialsand methods 7 sheep 12 Rugs woven from wool of experimental Old Navajo blankets and rugs 21 sheep- 7 Comparison of wool from experimental Old Navajo blankets and rugs 8 sheep with that in old blankets and rugs. 33 Summary 34 Literature cited 36 INTRODUCTION Hand weaving is an industry of considerable economic and social importance to the Navajo Indians (fig. 1). On and immediately adjacent to a reservation area of approxiiiiately 16 million acres in northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico/and southern Utah, nearly 50,000 Navajos make their home. Sheep raising has been the main occupation of these people for well over a century. After years of continued overgrazing, the land has become badly eroded and will not support a sheep industry of sufficient size to maintain the constantly growing Navajo population. The number of mature sheep and goats on the reservation has been reduced to about 550,000 head, but the total number of stock, in- cluding horses and cattle, is still considerably in excess of the carrying capacity of the range, according to estimates of the Soil Conservation Service, of the United States Department of Agriculture. -

Navajo Weavers

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION—BUREAU OF ETHNOLOGY. NAVAJO WEAVERS. BY Dr. WASHINOTON MATTHEWS, U. S. A. (371) ILLirSTKATIONS. Page. Platk XXXIV. —Navajo woman spinning 376 XXXV. —Weaving of diamnntl-shaped tliagonals 380 XXXVI.—Navajo woman weaving a belt 384 XXXVII.— Ziiiii women weaving a belt 388 XXXVIII.—Bringing down tbe batten 390 Fig. 42.—Ordinary Navajo blanket loom 378 43. —Diagram sbowing formation of warp 379 44.—Weaving of saddle-girtb 382 45. —Diagram showing arrangement of threads of tbe warp in tbe bealds and on the rod 383 46. —Weaving of saddle-girtb 383 47. —Diagram showing arrangement of healds in diagonal weaving. 384 48.—Diagonal cloth 384 49. —Navajo blanket of the finest quality 385 50. —Navajo blankets 386 51. —Navajo blanket 386 52. —Navajo blanket 387 53. —Navajo blanket 387 54. —Part of Navajo blanket 388 55. —Part of Navajo blanket 388 56. —Diagram showing formation of warp of sash 388 57. —Section of Navajo belt 389 53.—Wooden heaUl of the Zuuis 389 59. —Gix'l weaving (from an Aztec picture) 391 (373) NAVAJO WEAVERS. By Dr. Washington Matthews. § I. The art of weaving, as it exists among the Navajo Indians of New Mexico and Arizona, possesses points of great interest to the stu- dent of ethnography. It is of aboriginal origin ; and while European art has undoubtedly modifled it, the extent and nature of the foreign influence is easily traced. It is by no means certain, still there are many reasons for supposing, that the Navajos learned their craft from the Pueblo Indians, and that, too, since the advent of the Spaniards; yet the pupils, if such they be, far excel their masters to-day in the beauty and quality of their work. -

Library Author List 12:2020

SDCWG LIBRARY INVENTORY December 2020 SORTED BY AUTHOR Shelf Author Title Subject Location Abel, Isabel Multiple Harness Patterns Weaving Instruction Adelson, Laurie Weaving Tradition of Highland Bolivia Ethnic Textiles Adrosko, Rita Natural Dyes and Home Dyeing Dyeing Adrosko, Rita Natural Dyes in the United States Dyeing Ahnlund, Gunnila Vava Bilder (Swedish Tapestry) Ethnic Textiles Albers, Anni On Designing Design Albers, Anni On Weaving General Weaving Albers, Josef Interaction of Color Design Alderman, Sharon D. Handwoven, Tailormade Clothing Alderman, Sharon D. Handweaver's Notebook General Weaving Alderman, Sharon D. Mastering Weave Structures Weaving Patterns Alexander, Marthann Weaving Handcraft General Weaving Allard, Mary Rug Making Techniques and Design Rug Weaving Allen, Helen Louise American & European Hand Weaving General Weaving American Craft Museum Diane Itter: A retrospective Catalog American Tapestry American Tapestry Biennial I Tapestry Alliance American Tapestry American Tapestry Today Tapestry Alliance American Tapestry Panorama of Tapestry, Catalog Tapestry Alliance American-Scandinavian The Scandinavian Touch Ethnic Textiles Foundation Amos, Alden 101 Questions for Spinners Spinning 1 SDCWG LIBRARY INVENTORY December 2020 SORTED BY AUTHOR Shelf Author Title Subject Location Amsden, Charles A. Navaho Weaving Navajo Weaving Anderson, Clarita Weave Structures Used In North Am. Coverlets Weave Structures Anderson, Marilyn Guatemalan Textiles Today Ethnic Textiles Anderson, Sarah The Spinner’s Book of Yarn Designs -

FALL 06 ISSUE 11-9.Indd

People, Travel, Entertainment, Environment & Real Estate in the Southwest & Rockies Fall 2006 HOLIDAY GIFT-GIVING IDEAS INSIDE! JERRY ANDERSON: Silver Reef’s Renown Sculptor DAI: Building a Legacy of Fine Communities Majestic Lodge at Zion National Park Photo by Mark Breinholt Grapevine Radio for Women Colorland Photography Welcome to the Enchanting West Crisp mornings and bright sunny days Along the Wasatch Front, Development Associates Inc. is known for From the Publisher with trees beginning to drop their leaves. its legendary communities which are developed along the hill, dale, It’s harvest time. and mountainside areas of northern Utah. The partners have perfected PATTI M. EDDINGTON This issue is presents a bounteous these communities for the discerning buyer looking for real estate in offering of great reading and beautiful prime areas, with a diverse selection designed for young famillies or pictorials representing a fine collection of stories–and some fine writers empty-nesters. DAI knows that incorporating greenbelts, shade, ponds and photographers added to the harvest mix. and plenty of space into the natural environment will ensure their I have known of Jerry Anderson’s work since I studied fine art at the communities will thrive for generations to come. university and have always been a fan of bronze sculptures–masterful Denny’s Wigwam has been an icon on the tourists must-see list for renditions of humans and wildlife, all in fine form. decades. Located in Kanab on scenic byway US Hwy 89, buses by the A visit to Anderson’s gallery and studio at Silver Reef in Leeds, Utah, multitude stop daily, all year round. -

Navajo Weaving: Its Historic and Contemporary Perspectives

Navajo Weaving: Its Historic and Contemporary Perspectives Presented by Jerry Kerr March, 2006 Photo by Edward S. Curtis “For many generations weaving has been an integral part of the fabric of Navajo life. Monetary rewards are only a small part of the Navajo woman’s desire to weave. Weaving is a unifying force, an expression of personal pride and cultural identity, a spiritual experience, a tradition.” - Alice Kaufman and Christopher Selser Navajo Weaving Tradition: 1650 to the Present INTRODUCTION The Pueblo Culture of the American Southwest had been in the region for centuries, and the people had been weaving cotton for 500 years by the time the Navajo arrived in the area in the 1300s. While the pueblos focused on peaceful co-existence and domesticity, the Navajo, subsistence farmers themselves, raided other tribes and villages for their sustenance and wealth. This was the tenuous balance of power that the Spanish encountered when they first arrived in the region – a peaceful pueblo culture that was the dominant social influence in the area somewhat defenseless against the incursions of the raiding Navajo. Through the taking of pueblo slaves, the Navajo had been able to learn first-hand the intricacies of weaving spun cotton thread into fabric. The Navajos quickly adapted the pueblo loom to suit their own seasonally migratory lifestyle, and they have retained those adaptations to this day. They also designated weaving as women’s work, while it had been the responsibility of the men in the pueblos. By the time of the Spanish arrival in 1540 the Navajo weavers had already begun to surpass the pueblos in technical proficiency and design creativity. -

2006 MNA Navajo Textile Report

THE NAVAJO TEXTILE COLLECTION AT THE MUSEUM OF NORTHERN ARIZONA BY LAURIE D. WEBSTER, PH.D. JANUARY 2006 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 The Navajo Textile Collection at the Museum of Northern Arizona 4 Classic Period Textiles (to ca. 1870) 4 Late Classic Period Textiles (ca. 1868-1880) 4 Transition Period Blankets and Rugs (ca. 1880-1890) 5 Specialized Styles of the Nineteenth Century 7 Chief-style Blankets and Rugs 7 Women's Wearing Blankets 8 Women's Two-Piece Dresses 8 Rio Grande Influence ("Slave Blankets") 9 Moqui Pattern Blankets and Rugs 10 Wedge Weave Blankets 11 Germantown Blankets and Rugs 11 Overview of Textiles from the Early Rug Period (ca. 1890-1920) 12 Overview of Textiles from the Early Modern Period (ca. 1920-1940) 13 Overview of Textiles from the Modern Period (ca. 1940-present) 14 Regional Styles 14 Hubbell Revival Weavings 14 Ganado/Klagetoh Rugs 15 Early Crystal Rugs 16 Two Grey Hills Rugs 16 Teec Nos Pos Rugs 16 Red Mesa Outline Rugs 17 Early and Modern Chinle Rugs 17 Modern Crystal Rugs 18 Wide Ruins/Pine Springs Rugs 19 Burntwater Rugs 19 Nazlini Rugs 20 Sawmill Rugs 20 Other Specialized Styles and Miscellaneous Weavings 20 Storm Pattern Rugs 20 Modern Revival Rugs 21 Rugs with Compound Designs 21 Yei and Yeibichai Weavings 21 Sandpainting Rugs and Tapestries 22 Pictorial Weavings 23 Raised Outline Rugs 24 Tufted Rugs 24 Twill-woven Rugs and Saddle Blankets 25 Two-Faced Rugs and Saddle Blankets 26 Tailored and Non-Tailored Garments 26 Belts and Garters 26 Miscellaneous Textiles 27 Important Sub-Collections of Navajo Textiles at MNA 28 2 Summary and Recommendations 33 References Cited 36 Appendix I: List of Navajo Textiles at the Museum of Northern Arizona 37 Appendix II: Navajo Textiles in Good or Excellent Condition for Rotating Exhibit 61 3 INTRODUCTION The Museum of Northern Arizona is home to one of the largest and most important collections of Navajo textiles in the world. -

Guatemalan Backstrap Weaving the Mayan Civilization, Which Reached Its Peak Around Ad 300 to 900, Was Centered in the Central American Country of Guatemala

Weaving LEVELED BOOK • U Around the World A Reading A–Z Level U Leveled Book Word Count: 2,022 Weaving Around the World Written by Kira Freed Visit www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com for thousands of books and materials. Photo Credits: Front cover: © Christine Osborne/Corbis: back cover: © Kenneth Garrett/ National Geographic Stock; title page: © Travelscape Images/Alamy; page 3, 4, 15 (handbag), 21 (background),24 (right, bottom): Jupiterimages, Corporation, Inc.; page 5: © Ted Spiegel/Corbis; page 6: © Bettmann/Corbis; page 7: © Todd Gipstein/National Geographic Stock; page 8: © Julia Malakie/AP Images; page 10: Weaving © Michael S. Lewis/Corbis; page 11: © Catherine Karnow/Corbis; page 12: © Sergio Pitamitz/Corbis; page 13: © Sergio Pitamitz/Corbis; page 14: © Peter Scholey/Alamy; page 15 (main): © Dave Bartruff/Corbis; Page 16: © Michele Burgess/Alamy; page 17: © Nicholas Pitt/Digital Vision/Getty Images; page 18: © Margaret Courtney- Clarke/Corbis; page 19 (main): © Ariadne Van Zandbergen/Alamy; page 19 (inset): © Robert Estall photo agency/Alamy; page 20 (both): © Werner Forman/Corbis; Around the World page 22: © David Shen/epa/Corbis; page 24 (jeans): © Greg Kuchik/Photodisc/ Getty Image Front cover: Geometric shapes and stripes are just some of the patterns made using weaving. This is a Bedouin weaving. Back cover: Mayan teenagers attend Day of the Dead celebrations in traditional woven clothing. Title page: A Peruvian woman weaves using a foot loom. Weaving Around the World Level U Leveled Book Correlation © Learning A–Z LEVEL U Written by Kira Freed Written by Kira Freed Fountas & Pinnell Q All rights reserved. Reading Recovery 40 DRA 40 www.readinga-z.com www.readinga-z.com Introduction The art and craft of weaving are responsible for an amazing variety of objects in our world . -

Navajo Textiles: 1840 - 1910

Navajo Textiles: 1840 - 1910 Nov. 6 - Dec. 16, 1994 Johnson County CommunityCollege • Galle1yof A.11 Navajo Weaving the Spanish settled in the Rio Grand e Valley in 1598, they brou ght with them By the time the Spanish explorers the long , silky-fleece d churro sheep , discove red the American Southw est native to south ern Spain, to provide in 1540, the Pueblo Indian s had been food and wool for weaving on their weavers of cloth for well over a own version of the Europ ean treadle thou sand years. The Navajo Indians , loom . It wa s not long before yarns wh o had arrived only a hundr ed years spun from Spanish sheep's wool were or so before the Spanish, were not yet wov en into Pueblo cloth on their weavers, but before the advent of the wide, ve,tical loo m and dyed blue 18th centu1y, they too were destined with indigo dye, which the Spanish to beco me renowned for the produ c also introdu ced. tivity of their loom s. The Spanish, who Pueblo weaving was forever brou ght their own tradition of wea v chang ed. Brazilwoo d, logwood and ing to the Southwest in 1598, forever cochineal dyes came later, but threads altered the course of Pueblo weaving raveled from fine English and Spanish and were instrum ental in shaping the comm ercial cloth provid ed rich, deve lopm ent of that of the Navajo. cochine al-dyed crimson yarns that the Through time, Pueblo, Spanish and Pueblos used to deco rate their cloth in iVJokiSe rape , 1860-1870, 71" x 51", hand-spun avajo each influenced the other in weave , embroide1y and brocade. -

CHRISTINA JORDAN NARUSZEWICZ a Thesis Submitted to the Graduate

BEYOND BINARY: NAVAJO ALTERNATIVE GENDERS THROUGHOUT HISTORY BY: CHRISTINA JORDAN NARUSZEWICZ A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment requirements for the degree of MASTERS OF MUSEUM STUDIES IN HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY University of Central Oklahoma 2016 0 1 Acknowledgments I would like to thank the community of scholars I have worked with over the past two years within the University of Central Oklahoma (UCO). By working with professors and students as colleagues, I received community support that drove this research through the dead ends and quandaries. Firstly, I would like to sincerely thank Dr. Lindsey Churchill for her insight and friendship as both my graduate advisor and committee chair. Through her mentorship, I challenged myself both academically, professionally, and personally. Dr. Katrina Lacher, also on my committee, helped introduce me to the subject of Two-Spirit individuals and guided my research for the historiography of the subject. Dr. Patricia Loughlin, the Chair of the History and Geography Department, has shown a constant interest in my research and offered several research suggestions that provided critical insight for several chapters. To my friends and family thank you for you enduring support and patience. To the community of scholars at UCO, thank you for the debates and conversation. I would like to thank Neal Hampton for suggesting that I look into Newcomb’s Hosteen Klah: Navajo Medicine Man. A suggestion that jump-started this whole thesis. I am especially grateful to Alexander Larrea, for all the proof-reading, and last minute technology help sessions. Finally, my thesis would not have been possible without the services and efforts of the staff at several institutions. -

Art Teacher's Book of Lists

JOSSEY-BASS TEACHER Jossey-Bass Teacher provides educators with practical knowledge and tools to create a positive and lifelong impact on student learning. We offer classroom-tested and research-based teaching resources for a variety of grade levels and subject areas. Whether you are an aspiring, new, or veteran teacher, we want to help you make every teaching day your best. From ready-to-use classroom activities to the latest teaching framework, our value-packed books provide insightful, practical, and comprehensive materials on the topics that matter most to K–12 teachers. We hope to become your trusted source for the best ideas from the most experienced and respected experts in the field. TITLES IN THE JOSSEY-BASS EDUCATION BOOK OF LISTS SERIES THE SCHOOL COUNSELOR’S BOOK OF LISTS, SECOND EDITION Dorothy J. Blum and Tamara E. Davis • ISBN 978-0-4704-5065-9 THE READING TEACHER’S BOOK OF LISTS, FIFTH EDITION Edward B. Fry and Jacqueline E. Kress • ISBN 978-0-7879-8257-7 THE ESL/ELL TEACHER’S BOOK OF LISTS, SECOND EDITION Jacqueline E. Kress • ISBN 978-0-4702-2267-6 THE MATH TEACHER’S BOOK OF LISTS, SECOND EDITION Judith A. Muschla and Gary Robert Muschla • ISBN 978-0-7879-7398-8 THE ADHD BOOK OF LISTS Sandra Rief • ISBN 978-0-7879-6591-4 THE ART TEACHER’S BOOK OF LISTS, FIRST EDITION Helen D. Hume • ISBN 978-0-7879-7424-4 THE CHILDREN’S LITERATURE LOVER’S BOOK OF LISTS Joanna Sullivan • ISBN 978-0-7879-6595-2 THE SOCIAL STUDIES TEACHER’S BOOK OF LISTS, SECOND EDITION Ronald L. -

Spring 2020 Final Cover.Qxp 001 FALL 2006.Qxd 3/4/20 2:54 PM Page 1

spring 2020 final cover.qxp_001 FALL 2006.qxd 3/4/20 2:54 PM Page 1 AREA Spring 2020 We’ve made it our business to protect yours… Our mission is to protect our brick & mortar accounts by not offering our rugs to online retailers. What protection do you get from your rug vendors? Los Angeles . High Point . Las Vegas . Atlanta . Dallas www.jauntyinc.com CELEBRATING 40 YEARS OF FINE ARTISANAL HANDCRAFTED RUGS ATLANTA LAS VEGAS NEW YORK HIGH POINT KALATY.COM SOUMAK COLLECTION HIGH POINT SHOWROOM – IHFC, G-369 OPEN EARLY FRIDAY, APRIL 24 OPEN FOR MARKET APRIL 26 - 29 (CLOSED SATURDAY, APRIL 25) EXCLU SIVELY R U G S . BY D ESIGN. HIGH POINT IHFC G276 | OWRUGS.COM High Point market SHOWROOM H-345 April 25-29, 2020 MOMENI The Heirloom Collection. spring 2020 2.qxp_001 FALL 2006.qxd 3/7/20 3:02 PM Page 6 FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESK Dear Colleagues, I am honored and humbled to have been elected pres- More recently, technology has taken over offering ident of the ORIA, whose mission is to work vigor- vendors a single integrated digital platform that ously on issues important to our industry. My com- enhances and extends the physical markets, connect- mitment will be to continue those efforts and proudly ing hundreds of thousands buyers and sellers and carry the torch that has been passed to me from our opening new business opportunities for customers. previous presidents. The challenge is how to find a balance between We are at the start of a new decade with a new the “digital” ways and the “personal” (traditional) set of challenges. -

Devin Moisan Auctioneers, Inc. 75 Railroad Ave. Epping, NH 03042 Phone: (603) 953-0022

Devin Moisan Auctioneers, Inc. 75 Railroad Ave. Epping, NH 03042 Phone: (603) 953-0022 Spring Antiques Auction 6/19/2021 REGISTERING TO BID AND/OR PLACING A BID AT AUCTION LOT # INDICATES ACCEPTANCE OF THE FOLLOWING TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE. 1 Grand Tour Sculpture, Dancing Faun at Pompeii 500.00 - 800.00 A BUYER'S PREMIUM OF 25% WILL BE ADDED TO THE HAMMER Bronze, mounted on oval plinth base. PRICE OF EACH LOT, DISCOUNTED TO 20% FOR ABSENTEE PURCHASES. AN ADDITIONAL 3% FEE WILL BE ADDED ON CREDIT H: 30 in., W: 11 in., D: 18 in. CARD TRANSACTIONS. 2 Pair of Cast Iron Whippet Garden Ornaments 500.00 - 800.00 All items are sold 'AS-IS, WHERE-IS' WITH ALL FAULTS and WITH NO The pair seated upon oval plinth bases. EXPRESS OR IMPLIED WARRANTIES and ALL SALES ARE FINAL. Bidders are encouraged to register on third-party bidding platforms prior to H: 17 in.; W: 12 in.; D: 7 in. (each) the day of sale, as automatic bidder approval is not guaranteed. 3 American Cast Iron Twig Form Garden Bench 700.00 - 1,000.00 It is the purchaser's responsibility to inspect each lot as to condition, size, Attributed to James Beebe Foundry, New York. authenticity and rarity to determine his or her own level of interest. Lot descriptions do not contain condition information and the absence of a H: 33 in., W: 50 in., D: 22 in. condition report does not imply that an object is free of defects or restoration. Condition reports are provided as a courtesy to our buyers and 4 19th C.