Spatial Patterns of Distribution and Abundance of Harrisia Portoricensis, an Endangered Caribbean Cactus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Haseltonia Articles and Authors.Xlsx

ABCDEFG 1 CSSA "HASELTONIA" ARTICLE TITLES #1 1993–#26 2019 AUTHOR(S) R ISSUE(S) PAGES KEY WORD 1 KEY WORD 2 2 A Cactus Database for the State of Baja California, Mexico Resendiz Ruiz, María Elena 2000 7 97-99 BajaCalifornia Database A First Record of Yucca aloifolia L. (Agavaceae/Asparagaceae) Naturalized Smith, Gideon F, Figueiredo, 3 in South Africa with Notes on its uses and Reproductive Biology Estrela & Crouch, Neil R 2012 17 87-93 Yucca Fotinos, Tonya D, Clase, Teodoro, Veloz, Alberto, Jimenez, Francisco, Griffith, M A Minimally Invasive, Automated Procedure for DNA Extraction from Patrick & Wettberg, Eric JB 4 Epidermal Peels of Succulent Cacti (Cactaceae) von 2016 22 46-47 Cacti DNA 5 A Morphological Phylogeny of the Genus Conophytum N.E.Br. (Aizoaceae) Opel, Matthew R 2005 11 53-77 Conophytum 6 A New Account of Echidnopsis Hook. F. (Asclepiadaceae: Stapeliae) Plowes, Darrel CH 1993 1 65-85 Echidnopsis 7 A New Cholla (Cactaceae) from Baja California, Mexico Rebman, Jon P 1998 6 17-21 Cylindropuntia 8 A New Combination in the genus Agave Etter, Julia & Kristen, Martin 2006 12 70 Agave A New Series of the Genus Opuntia Mill. (Opuntieae, Opuntioideae, Oakley, Luis & Kiesling, 9 Cactaceae) from Austral South America Roberto 2016 22 22-30 Opuntia McCoy, Tom & Newton, 10 A New Shrubby Species of Aloe in the Imatong Mountains, Southern Sudan Leonard E 2014 19 64-65 Aloe 11 A New Species of Aloe on the Ethiopia-Sudan Border Newton, Leonard E 2002 9 14-16 Aloe A new species of Ceropegia sect. -

Caryophyllales 2018 Instituto De Biología, UNAM September 17-23

Caryophyllales 2018 Instituto de Biología, UNAM September 17-23 LOCAL ORGANIZERS Hilda Flores-Olvera, Salvador Arias and Helga Ochoterena, IBUNAM ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Walter G. Berendsohn and Sabine von Mering, BGBM, Berlin, Germany Patricia Hernández-Ledesma, INECOL-Unidad Pátzcuaro, México Gilberto Ocampo, Universidad Autónoma de Aguascalientes, México Ivonne Sánchez del Pino, CICY, Centro de Investigación Científica de Yucatán, Mérida, Yucatán, México SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Thomas Borsch, BGBM, Germany Fernando O. Zuloaga, Instituto de Botánica Darwinion, Argentina Victor Sánchez Cordero, IBUNAM, México Cornelia Klak, Bolus Herbarium, Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Town, South Africa Hossein Akhani, Department of Plant Sciences, School of Biology, College of Science, University of Tehran, Iran Alexander P. Sukhorukov, Moscow State University, Russia Michael J. Moore, Oberlin College, USA Compilation: Helga Ochoterena / Graphic Design: Julio C. Montero, Diana Martínez GENERAL PROGRAM . 4 MONDAY Monday’s Program . 7 Monday’s Abstracts . 9 TUESDAY Tuesday ‘s Program . 16 Tuesday’s Abstracts . 19 WEDNESDAY Wednesday’s Program . 32 Wednesday’s Abstracs . 35 POSTERS Posters’ Abstracts . 47 WORKSHOPS Workshop 1 . 61 Workshop 2 . 62 PARTICIPANTS . 63 GENERAL INFORMATION . 66 4 Caryophyllales 2018 Caryophyllales General program Monday 17 Tuesday 18 Wednesday 19 Thursday 20 Friday 21 Saturday 22 Sunday 23 Workshop 1 Workshop 2 9:00-10:00 Key note talks Walter G. Michael J. Moore, Berendsohn, Sabine Ya Yang, Diego F. Registration -

Harrisia Cactus Moonlight Cactus Harrisia Martinii, Harrisia Tortuosa and Harrisia Pomanensis

Restricted invasive plant Harrisia cactus Moonlight cactus Harrisia martinii, Harrisia tortuosa and Harrisia pomanensis Harrisia cactus can form dense infestations that will Legal requirements reduce pastures to a level unsuitable for stock. Harrisia cactus will choke out other pasture species Harrisia cactus (Harrisia martinii, Harrisia tortuosa and when left unchecked. Harrisia pomanensis) are category 3 restricted invasive plants under the Biosecurity Act 2014. It must not be The spines are a problem for stock management, given away, sold, or released into the environment. The interfering with mustering and stock movement. Act requires everyone to take all reasonable and practical Harrisia cactus produces large quantities of seed that is steps to minimise the risks associated with invasive plants highly viable and easily spread by birds and other animals. under their control. This is called a general biosecurity As well as reproducing from seed, harrisia cactus has long obligation (GBO). This fact sheet gives examples of how trailing branches that bend and take root wherever they you can meet your GBO. touch the ground. Any broken-off portions of the plant will take root and grow. At a local level, each local government must have a The cactus is shade tolerant and reaches its maximum biosecurity plan that covers invasive plants in its area. development in the shade and shelter of brigalow scrub, This plan may include actions to be taken on certain though established infestations can persist once scrub species. Some of these actions may be required under is pulled. local laws. Contact your local government for more Harrisia cactus is found in the Collinsville, Nebo, information. -

University of Florida Thesis Or Dissertation Formatting

SYSTEMATICS OF TRIBE TRICHOCEREEAE AND POPULATION GENETICS OF Haageocereus (CACTACEAE) By MÓNICA ARAKAKI MAKISHI A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2008 1 © 2008 Mónica Arakaki Makishi 2 To my parents, Bunzo and Cristina, and to my sisters and brother. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I want to express my deepest appreciation to my advisors, Douglas Soltis and Pamela Soltis, for their consistent support, encouragement and generosity of time. I would also like to thank Norris Williams and Michael Miyamoto, members of my committee, for their guidance, good disposition and positive feedback. Special thanks go to Carlos Ostolaza and Fátima Cáceres, for sharing their knowledge on Peruvian Cactaceae, and for providing essential plant material, confirmation of identifications, and their detailed observations of cacti in the field. I am indebted to the many individuals that have directly or indirectly supported me during the fieldwork: Carlos Ostolaza, Fátima Cáceres, Asunción Cano, Blanca León, José Roque, María La Torre, Richard Aguilar, Nestor Cieza, Olivier Klopfenstein, Martha Vargas, Natalia Calderón, Freddy Peláez, Yammil Ramírez, Eric Rodríguez, Percy Sandoval, and Kenneth Young (Peru); Stephan Beck, Noemí Quispe, Lorena Rey, Rosa Meneses, Alejandro Apaza, Esther Valenzuela, Mónica Zeballos, Freddy Centeno, Alfredo Fuentes, and Ramiro Lopez (Bolivia); María E. Ramírez, Mélica Muñoz, and Raquel Pinto (Chile). I thank the curators and staff of the herbaria B, F, FLAS, LPB, MO, USM, U, TEX, UNSA and ZSS, who kindly loaned specimens or made information available through electronic means. Thanks to Carlos Ostolaza for providing seeds of Haageocereus tenuis, to Graham Charles for seeds of Blossfeldia sucrensis and Acanthocalycium spiniflorum, to Donald Henne for specimens of Haageocereus lanugispinus; and to Bernard Hauser and Kent Vliet for aid with microscopy. -

At the Forefront of Conservation

TABLE OF CONTENTS DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Fiscal Year 2009 Budget Justifications Table of Contents General Statement.... ........... .....................................................................................GS-1 Organization Chart.... ........... .....................................................................................GS-2 Overview of Fiscal Year 2009 Request.......................................................................GS-3 Goal Performance Table....... ..................................................................................... PT-1 Budget At-A-Glance Table .... .....................................................................................BG-1 Appropriation: Resource Management Appropriations Language ............................................................................... RM-1 Authorizing Statutes .. .................................................................................... RM-1 Summary of Requirements........................................................................... RM-11 Justification of Fixed Costs and Related Changes....................................... RM-12 Program & Financing Schedules/Object Class/Personnel Summary........... RM-14 Endangered Species Overview........ ..................................................................................... ES-1 Candidate Conservation...................................................................... ES-7 Listing ............................................................................................. -

Redalyc.Stem and Root Anatomy of Two Species of Echinopsis

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad ISSN: 1870-3453 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México dos Santos Garcia, Joelma; Scremin-Dias, Edna; Soffiatti, Patricia Stem and root anatomy of two species of Echinopsis (Trichocereeae: Cactaceae) Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, vol. 83, núm. 4, diciembre, 2012, pp. 1036-1044 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=42525092001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 83: 1036-1044, 2012 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.28124 Stem and root anatomy of two species of Echinopsis (Trichocereeae: Cactaceae) Anatomía de la raíz y del tallo de dos especies de Echinopsis (Trichocereeae: Cactaceae) Joelma dos Santos Garcia1, Edna Scremin-Dias1 and Patricia Soffiatti2 1Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, CCBS, Departamento de Biologia, Programa de Pós Graduação em Biologia Vegetal Cidade Universitária, S/N, Caixa Postal 549, CEP 79.070.900 Campo Grande, MS, Brasil. 2Universidade Federal do Paraná, SCB, Departamento de Botânica, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Botânica, Caixa Postal 19031, CEP 81.531.990 Curitiba, PR, Brasil. [email protected] Abstract. This study characterizes and compares the stem and root anatomy of Echinopsis calochlora and E. rhodotricha (Cactaceae) occurring in the Central-Western Region of Brazil, in Mato Grosso do Sul State. Three individuals of each species were collected, fixed, stored and prepared following usual anatomy techniques, for subsequent observation in light and scanning electronic microscopy. -

Fragrant Prickly-Apple Cereus Eriophorus Var

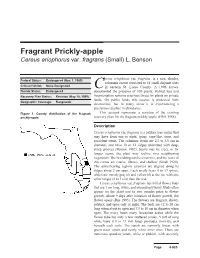

Fragrant Prickly-apple Cereus eriophorus var. fragrans (Small) L. Benson ereus eriophorus var. fragrans is a rare, slender, Federal Status: Endangered (Nov. 1, 1985) columnar cactus restricted to 11 small disjunct sites Critical Habitat: None Designated Cin eastern St. Lucie County. A 1996 survey Florida Status: Endangered documented the presence of 320 plants. Habitat loss and fragmentation remains a serious threat for plants on private Recovery Plan Status: Revision (May 18, 1999) lands. On public lands this species is protected from Geographic Coverage: Rangewide destruction, but in many areas it is experiencing a precipitous decline in abundance. This account represents a revision of the existing Figure 1. County distribution of the fragrant prickly-apple. recovery plan for the fragrant prickly-apple (FWS 1988). Description Cereus eriophorus var. fragrans is a solitary tree cactus that may have from one to eight, spiny, cane-like, stout, and succulent stems. The columnar stems are 2.5 to 5.0 cm in diameter, and have 10 or 12 ridges alternated with deep, sharp grooves (Benson 1982). Stems may be erect, or for longer stems, the plant may recline over neighboring vegetation. The branching can be extensive, and the roots of this cactus are coarse, fibrous, and shallow (Small 1920). The spine-bearing regions (areoles) are aligned along its ridges about 2 cm apart. Each areole bears 9 to 13 spines, which are mostly grayish and yellowish at the tip, with one spine longer (2 to 4 cm) than the rest. Cereus eriophorus var. fragrans has initial flower buds that are 1 cm long, white, and exceedingly hairy. -

ON the TAXONOMY of CACTACEAE JUSS by the EVIDENCE of SEED MICROMORPHOLOGY and SDS-PAGE ANALYSIS Lamiaa F

European Journal of Botany, Plant Sciences and Phytology Vol.2, No.3, pp.1-15, October 2015 ___Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) ON THE TAXONOMY OF CACTACEAE JUSS BY THE EVIDENCE OF SEED MICROMORPHOLOGY AND SDS-PAGE ANALYSIS Lamiaa F. Shalabi Department of Biological and Geological Sciences, Faculty of Education, Ain Shams University, Cairo, Egypt. Biology Department, Faculty of Sciences, Jazan University, Jazan, Saudi Arabia. ABSTRACT Numerical classification of 16 taxa of Cactaceae was studied using combination of micromorphological characters of seeds (using L.M and SEM) and SDS- PAGE analysis. Aspects of seed micromorphology and seed protein variation as defined were recorded and scored comparatively for the OTU's into a data matrix. Phenetic relationships of these taxa were established based on UPGMA-clustering method by using Jaccard coefficient of the NTSYS-pc 2.2 program. The results were compatible with the traditional relationships of some taxa as the split-off of Opuntia humifusa and Astrophytum myriostigma, at separate lines, these results are compatible with their placement in tribes Opuntieae (subfamily Opuntioideae) and Cacteae (Subfamily cactoideae) respectively, at the time, the placement of three taxa Pseudorhipsalis ramulosa, Rhipsalis baccifera Accession 1, and Rhipsalis baccifera Accession 2 together, the clustering of Hylocereus triangularis and Neobuxbaumia euphorbioides together at a unique tribe Phyllocacteae. The findings contradict in a number of cases the traditional studies, as the grouping of Trichocereus vasquezii with the two represents of genus Parodia despite of their placement in different tribes. KEYWORDS: Cactaceae, SDS-PAGE, Seed micromorpgology, SEM INTRODUCTION The Cactaceae are an exciting and problematic group of plants because of their varied morphology, succulence, and their showy flowers (Barthlott and Hunt 1993). -

Appendix A. Plant Species Known to Occur at Canaveral National Seashore

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Vegetation Community Monitoring at Canaveral National Seashore, 2009 Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2012/256 ON THE COVER Pitted stripeseed (Piriqueta cistoides ssp. caroliniana) Photograph by Sarah L. Corbett. Vegetation Community Monitoring at Canaveral National Seashore, 2009 Natural Resource Report NPS/SECN/NRDS—2012/256 Michael W. Byrne and Sarah L. Corbett USDI National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network Cumberland Island National Seashore 101 Wheeler Street Saint Marys, Georgia, 31558 and Joseph C. DeVivo USDI National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network University of Georgia 160 Phoenix Road, Phillips Lab Athens, Georgia, 30605 March 2012 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for the timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. Consequently, the initial analyses of data in this report are provisional and subject to change. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. -

TAXON:Harrisia Eriophora (Pfeiff.)

TAXON: Harrisia eriophora (Pfeiff.) SCORE: 7.0 RATING: High Risk Britton Taxon: Harrisia eriophora (Pfeiff.) Britton Family: Cactaceae Common Name(s): fragrant apple cactus Synonym(s): Cereus eriophorus Pfeiff. fragrant prickly apple jijira pitahaya woolly prickly apple Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 9 Oct 2017 WRA Score: 7.0 Designation: H(HPWRA) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Tropical Cactus, Spiny, Edible Fruit, Spreads Vegetatively, Bird-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 n Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 n outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 n 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed n=0, y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2) y 401 -

Notes on Florida's Endangered and Threatened Plants 1

NOTES ON FLORIDA'S ENDANGERED AND THREATENED PLANTS 1 Nancy C. Coile2 The Regulated Plant Index is based on information provided by the Endangered Plant Advisory Council (EPAC), a group of seven individuals who represent academic, industry, and environmental interests (Dr. Loran C. Anderson, Dr. Daniel F. Austin,. Mr. Charles D. D aniel III, Mr. David M . Drylie, Jr., Ms. Eve R. Hannahs, Mr. Richard L. Moyroud, and Dr. Daniel B. Ward). Rule Chap. 5B-40, Florida Administrative Code, contains the "Regulated Plant Index" (5B-40.0055) and lists endangered, threatened, and commercially exploited plant species for Florida; defines the categories; lists instances where permits may be issued; and describes penalties for vio lations. Copies of this Rule may be obtained from Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services, Division of Plant Industry, P. O. Box 147100, Gainesville, Fl 32614-7100. Amended 20 September 2000, the "Regulated Plant Index" contains 415 endangered species, 113 threatened species, and eight commercially exploited species. Descriptions of these rare species are often difficult to locate. Florida does not have a single manual covering the flora of the entire state. Long and Lakela s manual (1971) focuses on the area south of Glades County; Clewell (1985) is a guide for the Panhandle; and Wunderlin (1998) is a guide for the entire state of Florida but lacks descriptions. Small (1933) is an excellent resource, but must be used with great care since the nomenclature is outdated and frequently disputed. Clewell (1985) and Wunderlin (1998 ) are guides with keys to the flora, but lack species descriptions. Distribution maps (Wund erlin and Hansen, 200 0) are available over the Internet through the University of South Florida Herbarium [www.plantatlas.usf.edu/]. -

Chapter 14. Wildlife and Forest Communities 341

chapteR 14. Wildlife and Forest Communities 341 Chapter 14. Wildlife and Forest communities Margaret Trani Griep and Beverly Collins1 key FindingS • Hotspot areas for plants of concern are Big Bend National Park; the Apalachicola area of the Southern Gulf Coast; • The South has 1,076 native terrestrial vertebrates: 179 Lake Wales Ridge and the area south of Lake Okeechobee amphibians, 525 birds, 176 mammals, and 196 reptiles. in Peninsular Florida; and coastal counties of North Species richness is highest in the Mid-South (856) and Carolina in the Atlantic Coastal Plain. The Appalachian- Coastal Plain (733), reflecting both the large area of these Cumberland highlands also contain plants identified by subregions and the diversity of habitats within them. States as species of concern. • The geography of species richness varies by taxa. • Species, including those of conservation concern, are Amphibians flourish in portions of the Piedmont and imperiled by habitat alteration, isolation, introduction of Appalachian-Cumberland highlands and across the Coastal invasive species, environmental pollutants, commercial Plain. Bird richness is highest along the coastal wetlands of development, human disturbance, and exploitation. the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico, mammal richness Conditions predicted by the forecasts will magnify these is highest in the Mid-South and Appalachian-Cumberland stressors. Each species varies in its vulnerability to highlands, and reptile richness is highest across the forecasted threats, and these threats vary by subregion. Key southern portion of the region. areas of concern arise where hotspots of vulnerable species • The South has 142 terrestrial vertebrate species coincide with forecasted stressors. considered to be of conservation concern (e.g., global • There are 614 species that are presumed extirpated from conservation status rank of critically imperiled, imperiled, selected States in the South; 64 are terrestrial vertebrates or vulnerable), 77 of which are listed as threatened or and 550 are vascular plants.