The Badoh-Pathari Saptamātṛ Panel Inscription

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rajgarh ( State : -Madhya Pradesh)

Annex-A SERVICE AREA PLAN OF DISTRICT – RAJGARH ( STATE : -MADHYA PRADESH) NAME OF THE BLOCK - RAJGARH Place of BR/BCA/ATM Name of Bank & Name of Gram Panchayat Name of Revenue Population of Post Village of Branch Village (Provide all Revenue office/Sub 2000(2001 villages Village(2001 Post Office Census name founding Census) (Provide Yes/No Population) one Gram Population of Panchayat ) all the villages which is being mentioned in SAP) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 BAKHED Branch/BC NMGB BAKHED BAKHED 3223 YES Khujner One village Panchayat KARANWAS Branch BANK OF INDIA KARANWAS KARANWAS 2457 YES KARANWAS One village Panchayat KAREDI Branch BANK OF INDIA KAREDI KAREDI 3013 YES KAREDI One village Panchayat 1 Annex-A SERVICE AREA PLAN OF DISTRICT – RAJGARH ( STATE : -MADHYA PRADESH) NAME OF THE BLOCK -- KHILCHIPUR Place of Village of BR/BCA Name of Bank & Name of Gram Panchayat Name of Revenue Population of Post 2000(2001 Census /ATM Branch Village (Provide all Revenue office/Su Population) villages Village(2001 b Post name founding one Census) (Provi Office Gram Panchayat ) de Yes/No Population of all the villages which is being mentioned in SAP) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 BHATKHEDA BC BANK OF INDIA BHATKHEDA BHATKHEDA 2797 YES Chhapiheda One village Panchayat BHOJPUR BC NMGB BHOJPUR BHOJPUR 2331 YES Khilchipur One village Panchayat KHAJURI -GOKUL Branch BANK OF INDIA KHAJURI- GOKUL KHAJURI -GOKUL 2215 YES Chhapiheda One village Panchayat PIPLIYA KALAN Branch BANK OF INDIA PIPLIYA KALAN PIPLIYA KALAN 2787 NO Jaitpurkalan One village Panchayat RANARA BC BANK OF INDIA -

District Census Handbook, Raisen, Part X

CENSUS OF INDIA 1971 SERIES 10 MADHYA PR ADESH DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK PART X (A) & (B) VILLAGE AND TOWN DIRECTORY VILLAGE AND TOWN-WISE PRIMARY CENSUS ABSTRACT RAISEN DISTRICT A. K. PANDYA OP THE INDIAN ADMINISTRATIVE SERVICE DIRECTOR OF CENSUS OPERATIONS. MADHYA PRADESH PUBLISHED BY THE GOVERNMENT OF MADHYA PRA.DESH 1974 CONTENTS Page 1. Preface i-ii 2. List of Abbreviations 1 3. Alphabetical List of Villages 3-19 ( i ) Raisen Tahsil 3-5 ( ii) Ghairatganj Tahsil 5-7 ( iii) Begmaganj Tahsil 7-9 (iv) Goharganj Tahsil 9-12 ( v) Baraily Tahsil 12-15 (vi) Silwani Tahsil 15-17 ( vii) Udaipura Tahsil 17-19 PART A 1. Explaaatory Note 23-33 2. Village Directory (Amenities and Land-use) 34·101 ( i ) Raisen Tahsil 34-43 ( ii) Ghairatganj Tahsil 44-51 ( iii) Begamganj Tahsil 52·61 (iv) Goharganj Tahsil, 62-71 (v ) Baraily Tahsil 72-81 (vi), Silwani Tahsil 82-93 (vii ) Udaipura Tahsil 94-101 3. Appendix to Village Directery 102-103 4. Town Directory 104-107 ( i) Status, Growth History and Functional Category of Towns 104 (ii) Physical Aspects and Location of Towns 104 ( iii) Civic Finance 105 ( iv) Civic and other Amenities 105 ( v) Medical, Educational, Recreational and Cultural Facilities in Towns 106 (vi) TradCt Commerce, Industry and Banking 106 t vii) Population by R.eligion and Scheduled Castes/Scheduled Tribes in Towns 107 PART B tJago 1. Explaaatory Note 111·112 2. Figures at a Glance 113 3. Primary Census Abstract 114·201 District Abstract 114-117 Raisen Tahsil 118·133 (Rural) Il8·133 (Urban) 132·133 Ghairatganj Tahsil 134-141 (Rural) 134·141 Begamganj Tahsil 142.153 (Rural) 142·151 (Urban) ISO-I53 Goharganj Tahsil 154-167 (Rural) 154-167 Baraily Tahsil 168-181 (Rural) 168-181 (Urban) 180·181 Silwani Tahsil 182·193 (Rural) 182-193 Udaipura Tahsil 194-201, (Rural) 194-201 LIST OF ABBREVJATIONS I. -

Rdwr New.Xlsx

ादेशक मौसम पूवानुमान के Regional Weather Forecasting Centre ादेशक मौसम के Regional Meteorological Centre भारत मौसम वान वभाग India Meteorological Department नागपुर Nagpur Regional Daily Weather Report Friday, 18 June 2021 Issue Time : 12:00 Hrs. IST Monsoon Watch ♦Southwest Monsoon has further advanced into some more parts of north Arabian Sea, most parts of Gujarat region, some parts Saurashtra, southeast Rajasthan and some more parts of Madhya Pradesh and Uttar Pradesh today, the 18th June 2021. ♦ The Northern Limit of Monsoon (NLM) passes through lat. 21.5°N/ Long. 60°E, Junagarh, Deesa, Guna, Kanpur, meerut, Ambala and Amritsar (refer Fig 1 for Northern Limit of the southwest Monsoon 2021 as on 18th June 2021). ♦ Conditions are favorable for further advance of southwest monsoon into remaining parts of north Arabian Sea and Gujarat state, some more parts of south Rajasthan, west Uttar Pradesh and remaining parts of Madhya Pradesh during next 24 hours. Main Weather Observations Very heavy rainfall occurred at isolated places over East Madhya Pradesh, heavy rainfall occurred at isolated places over East Madhya Pradesh & Chhattisgarh. Light to moderate rainfall occurred at many places over East Madhya Pradesh & Chhattisgarh & at few places over West Madhya Pradesh. Thunderstorm with lightning observed at many places over Chhattisgarh& at isolated places over Madhya Pradesh & Vidarbha. Rainfall(cm) Chief Amount of Rainfall (1cm & above) : West Madhya Pradesh: : Sitamau (distMandsaur) 7, Nateran (distVidisha) 5, Ganjbasoda (distVidisha) -

Sonagiri: Steeped in Faith

T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Datia Palace: Forgotten Marvel of Bundelkhand Sonagiri: Steeped in Faith Dashavatar Temple: A Gupta-Era Wonder Deogarh’s Buddhist Caves Chanderi and its weaves The Beauty of Shivpuri Kalpi – A historic town I N T R O D U C T I O N Jhansi city also serves as a perfect base for day trips to visit the historic region around it. To the west of Jhansi lies the city of Datia, known for the beautiful palace built by Bundela ruler Bir Singh Ju Dev and the splendid Jain temple complex known as Sonagir. To the south, in the Lalitpur district of Uttar Pradesh lies Deogarh, one of the most important sites of ancient India. Here lies the famous Dashavatar temple, cluster of Jain temples as well as hidden Buddhist caves by the Betwa river, dating as early as 5th century BCE. Beyond Deogarh lies Chanderi , one of the most magnificent forts in India. The town is also famous for its beautiful weave and its Chanderi sarees. D A T I A P A L A C E Forgotten Marvel of Bundelkhand The spectacular Datia Palace, in Datia District of Madhya Pradesh, is one of the finest examples of Bundelkhand architecture that arose in the late 16th and early 17th centuries in the region under the Bundela Rajputs. Did you know that this palace even inspired Sir Edward Lutyens, the chief architect of New Delhi? Popularly known as ‘Govind Mahal’ or ‘Govind Mandir’ by local residents, the palace was built by the powerful ruler of Orchha, Bir Singh Ju Dev (r. -

Chief Engineers of At{ States/ Uts Pubtic Works Subject: Stand

p&M n No. NH- 1501 7 / 33 t2A19 - lllnt r Govennment of India $ Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (Ptanning Zone) Transport Bhawan, 1, Partiarnent street, I.{ew Dethi - 110001 Dated the 16th August, 2019 To 1. The PrincipaL secretaries/ secretaries of atl states/ UTs Pubtic Works Departments dealing with National Highways, other centratty Sponsored Schemes & State Schemes 2. Engineers-in-Chief/ The Chief Engineers of at{ States/ UTs pubtic works Departments deating with National Highways, Other Centpatty Sponsored Schemes 3. The Chairman, Nationa[ Highways Authority of India (NHAI), G-5&6, Sector-10, Dwarka, New Dethi- 1rc075 4. The Managing Director, NHIDCL, 3'd Floor, PTI Buitding, 4-parliament Street, New Dethi - 110001 5. Director General (Border Roads), Seema Sadak Bhawan, 4- partiament Street, New Dethi - 1 10001 6. Att CE ROs / SE ROs Subject: Standard Operating Procedure for installation of kilometer stone as per rationalization in the numbering system of NHs and thereby renumbered NHs- Reg. Sir/ Madam, Ptease find enctosed herewith the Standard Operating Procedure for installation of kilometer stone as per rationalization in the numbering system of NHs and thereby renumbered NHs. State wise sanction ceiting is enclosed at Enclosure-;. is 2' lt requested to bring these to the notice of att concerned for comptiance with immediate effect and untiI further orders. 3- This issues with the concurrence of the Finance wing vide u.o. No. 356/TF-ll, dated 25 and approvat of the competent Authority. rs faithfulty, (5.P. Choudhary) Under Secretary to the rnment of India Tet. No. 01 1-23n9A28 f,nctosure: As above Page 1 of 57 c:\users\Hemont Dfiawan\ Desktop\Finat_sop_NH_km*stone*new_l.JH_ l6.0g.2019.doc - No. -

District Census Handbook, Bhopal, Part XIII-B, Series-11

"lif XIII -. 'fiT • • ~. ,,1.1-, "T1;cft~ 5I"lImrfif'li 6~J f;{~w", ~;:rqwr;:rr 'itA!' sr~1!f 1981 CENSUS-PUBLICATION PLAN (1981 Cemuv Pub!icatil')m, Series 11 Tn All India Series will be pu!J/is1led ill '!le fJllowing PlJl'1s) GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PUBLiCATIONS Part I-A Administration Report-Enumeration Part I-B Administration Report-Tabulation Part I1.~ General Population Tables Part II-B Primary Census Abstract Part III General Economic Tables Part IV Social and Cultural Tables Part V Migration Tables Part VI Fertility Tables Part VJI Tables on Houses and Diiabled PopulatioD Part VIII llousehold Tables Part IX SJX:cial Tables on Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes Part X-A Town Directory Part x-B Survey Reporti on 5elected Towns Part X-C Survey Reports on selected Villages Part XI Ethnographic Notes and special studie. on Scheduled Castel and Scheduled Tribes Part XII Census Atlas Paper I of 1982 Primary Census Abstra~t for Sc!1eduled Castes and Schedul cd Tribes Paper 1 of 1984 Household Population by Religion of Head or Hou':lehold STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS Part XIII-A&B District CetlslIs H:mdbook for each of the 45 districts in the State. (Village and Town Directory and Primary Census Abstract) comE~TS T'O Pages Foreword i-iv Preface v-vi District Map I'llportant Statistics vii Analytical Note ix-xxxiv ~lell'Tl'~lIi fecq-urr, 81'~~f:qa ;snfa 81"h: ari!~t~i.'I' Notes & Explanations, List of Scheduled Castes and Sched uled Tribes Order iil'rr~Tfo Off ~ifr (<<w)arr), mTl1ifi 1976, (Amendment) Act. -

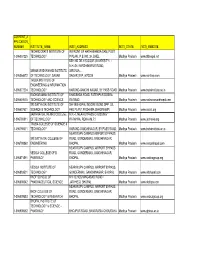

Y CURRENT a PPLICATION NUMBER INSTITUTE NAME

CURRENT_A PPLICATION_ NUMBER INSTITUTE_NAME INSTI_ADDRESS INSTI_STATE INSTI_WEBSITE TECHNOCRATS INSTITUTE OF IN FRONT OF HATHAIKHEDA DAM, POST 1-396057225 TECHNOLOGY PIPLANI, P.B. NO. 24, BHEL Madhya Pradesh www.titbhopal.net BEHIND DR.H.S.GOUR UNIVERSITY, N.H.-26, NARSHINGPUR ROAD, SWAMI VIVEKANAND INSTITUTE SIRONJA, 1-396064472 OF TECHNOLOGY, SAGAR SAGAR (M.P.) 470228 Madhya Pradesh www.svnitmp.com TRUBA INSTITUTE OF ENGINEERING & INFORMATION 1-396077204 TECHNOLOGY KAROND-GANDHI NAGAR, BY PASS ROAD Madhya Pradesh www.trubainstitute.ac.in RADHARAMAN INSTITUTE OF BHADBHDA ROAD, FATEHPUR DOBRA, 1-396649415 TECHNOLOGY AND SCIENCE RATIBAD Madhya Pradesh www.radharamanbhopal.com SRI SATYA SAI INSTITUTE OF SH-18,BHOPAL INDORE ROAD,OPP. OIL 1-396697631 SCIENCE & TECHNOLOGY FED PLANT,PACHAMA SEHORE(MP) Madhya Pradesh www.sssist.org JAWAHARLAL NEHRU COLLEGE N.H.-7, NEAR BYPASS CROSSING 1-396790811 OF TECHNOLOGY RATAHRA,,( REWA (M.P.)) Madhyya Pradesh www.jnctrewa.orgjg TRUBA COLLEGE OF SCIENCE & 1-396798671 TECHNOLOGY KAROND-GANDHINAGAR, BY PASS ROAD. Madhya Pradesh www.trubainstitute.ac.in NEAR RGPV CAMPUS AIRPORT BY-PASS SRI SATYA SAI COLLEGE OF ROAD, GONDERMAU, GANDHINAGAR, 1-396798862 ENGINEERING BHOPAL Madhya Pradesh www.ssscebhopal.com NEAR RGPV CAMPUS, AIRPORT BYPASS VEDICA COLLEGE OF B. ROAD, GONDERMAU, GANDHINAGAR, 1-396871591 PHARMACY BHOPAL Madhya Pradesh www.vedicagroup.org VEDICA INSTITUTE OF NEAR RGPV CAMPUS, AIRPORT BYPASS, 1-396893501 TECHNOLOGY GONDERMAU, GANDHINAGAR, BHOPAL Madhya Pradesh www.vitbhopal.com RKDF SCHOOL OF NH-12,HOSHANGABAD ROAD 1-396898342 PHARMACEUTICAL SCIENCE JATKHEDI, BHOPAL Madhya Pradesh www.rkdfsps.com NEAR RGPV CAMPUS, AIRPORT BYPASS RKDF COLLEGE OF ROAD, GONDERMAU, GANDHINAGAR, 1-396899583 TECHNOLOGY & RESEARCH BHOPAL Madhya Pradesh www.vedicagroup.org BHOPAL INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY & SCIENCE - 1-396908662 PHARMACY BHOJPUR ROAD, BANGRASIA CHOURAHA Madhya Pradesh www.globus.ac.in OPP. -

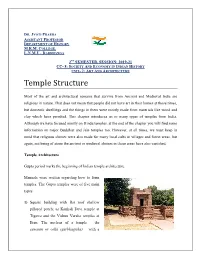

Temple Structure

DR. JYOTI PRABHA ASSISTANT PROFESSOR DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY M.R.M. COLLEGE, L.N.M.U., DARBHANGA 2ND SEMESTER, SESSION: 2019-21 CC- 8: SOCIETY AND ECONOMY IN INDIAN HISTORY UNIT- 2: ART AND ARCHITECTURE Temple Structure Most of the art and architectural remains that survive from Ancient and Medieval India are religious in nature. That does not mean that people did not have art in their homes at those times, but domestic dwellings and the things in them were mostly made from materials like wood and clay which have perished. This chapter introduces us to many types of temples from India. Although we have focused mostly on Hindu temples, at the end of the chapter you will find some information on major Buddhist and Jain temples too. However, at all times, we must keep in mind that religious shrines were also made for many local cults in villages and forest areas, but again, not being of stone the ancient or medieval shrines in those areas have also vanished. Temple Architecture Gupta period marks the beginning of Indian temple architecture. Manuals were written regarding how to form temples. The Gupta temples were of five main types: 1) Square building with flat roof shallow pillared porch; as Kankali Devi temple at Tigawa and the Vishnu Varaha temples at Eran. The nucleus of a temple – the sanctum or cella (garbhagriha) – with a single entrance and apporch (Mandapa) appears for the first time here. 2) An elaboration of the first type with the addition of an ambulatory (paradakshina) around the sanctum sometimes a second storey; examples the Shiva temple at Bhumara(M.P.) and the lad-khan at Aihole. -

M.A. in Sanskrit CBCS Pattern

Bankura University Department of Sanskrit CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM (CBCS): The CBCS provides an opportunity for the students to choose courses from the prescribed courses (Core Courses, Foundational Courses, Elective Courses). The courses can be evaluated following the grading system. M A in Sanskrit Programme details: Programme Objectives: This programme tries to aware students of the holistic approach of Sanskrit literature and as well as the modern studies, researches and approaches towards Sanskrit Studies. There are papers from different disciplines of Sanskrit studies, such as Veda, Literature, Grammar, Philosophy etc. Not only that the programme has comparative studies on western methods of literary theory, and interpretation. In the philosophy section one unit describes western methods of logic. Computational Linguistics is also introduced. Understanding of the idea of the research will be nurtured through the course on writing term paper. Major elective courses will initiate the student in a selected area providing in depth and comprehensive understanding of that area. The main aim of this programme is to train students in a way that they would able to do further research on their respective fields. This programme would also help student to be competent as a next- generation teacher of Sanskrit. Programme Specific Outcome: This programme will enable students to have a comprehensive idea of Sanskrit literature. It is expected that the course would form the knowledge and basic skills for the students to take up various teaching assignments and to pursue further research in the field. Assessment Methods: In most of the courses, especially in core courses and in major elective courses the medium of instruction in the class primarily will be Sanskrit. -

District Survey Report District: Vidisha Madhya Pradesh

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT DISTRICT: VIDISHA MADHYA PRADESH AS PER NOTIFICATION OF MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE. GOVT. OF INDIA, NEW DELHI, NO. S.O. 141(E), THE 15TH JANUARY, 2016 DIRECTORATE OF GEOLOGY AND MINING, M.P. MINERAL RESOURCE DEPARTMENT, GOVT OF M. P. BHOPAL [email protected] 2016 CONTENT S.N. Subject 1 Introduction 2 General 3 Geomorphology 4 Geology 5 Mineral Resources 6 Overview of Mining activity in the District 7 Details of Royalty or revenue received in last three years 8 Details of production of sand or bajari or minor mineral in the last three years 9 The list of Mining Lease in the District with location, area and period of validity 10 Drainage 11 Process of deposition of sediment in the river of the district 12 General profile of district 13 Rainfall 14 Land utilization patter in the district 15 Mineral Potential 16 Geological And Mineral Map 17 Map Index 18 Geomorphological Map 19 Geohydrological Map 20 Geotechnicaland Natural Hazards Map 21 Land use Map 1.INTRODUCTION As per the order issued by the Mineral Resources department Govt of M P the District Survey Report is to be prepared for the fulfilment of the notification of the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate change Govt of India dated Jan. 15th 2016. “MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE NOTIFICATION New Delhi, the 15th January, 2016 S.O. 141(E).—Whereas in exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (1) and clause (v) of sub-section (2) of section 3 of the Environment (Protection) Act, 1986 (29 of 1986), read with -

Madhya Pradesh.Xlsx

Madhya Pradesh S.No. District Name of the Address Major Activity Broad NIC Owner Emplo Code Establishment Description Activity ship yment Code Code Class Interval 130MPPGCL (POWER SARNI DISTT POWER 07 351 4 >=500 HOUSE) BETUL(M.P.) DISTT GENERATION PLANT BETUL (M.P.) 460447 222FORCE MOTORS ARCADY, PUNE VEHICAL 10 453 2 >=500 LTD. MAHARASHTRA PRODUCTION 340MOIL BALAGHAT OFFICER COLONEY MAINING WORK 05 089 4 >=500 481102 423MARAL YARN KHALBUJURG A.B. CLOTH 06 131 2 >=500 FACTORY ROAD MANUFACTRING 522SHRI AOVRBINDO BHOURASALA HOSPITAL 21 861 3 >=500 MEDICAL HOSPITAL SANWER ROAD 453551 630Tawa mines pathakheda sarni COOL MINING WORK 05 051 1 >=500 DISTT BETUL (M.P.) 460447 725BHARAT MATA HIGH BAJRANG THREAD 06 131 1 >=500 SCHOOL MANDAWAR MOHHALLA 465685 PRODUCTION WORK 822S.T.I INDIA LTD. PITHAMPUR RING MAKING OF 06 141 2 >=500 ROAD 453332 READYMADE CLOTHS 921rosi blue india pvt.ltd sector no.1 454775 DAYMAND 06 239 3 >=500 COTIND&POLISING 10 30 SHOBHAPUR MINSE PATHAKERA DISTT COL MININING 05 051 4 >=500 BETUL (M.P.) 440001 11 38 LAND COLMINCE LINE 0 480442 KOLMINCE LAND 05 089 1 >=500 OFFICE,MOARI INK SCAPE WORK 12 44 OFFICE COAL MINES Bijuri OFFICE COAL COAL MINES 05 051 1 >=500 SECL BILASPUR MINES SECL BILASPUR Korja Coliery Bijuri 484440 13 38 W.C.L. Dist. Chhindwara COL MINING 05 051 4 >=500 480559 14 22 SHIWALIK BETRIES PANCHDERIYA TARCH FACTORY 06 259 2 >=500 PVT. LTD. 453551 15 33 S.S.E.C.N. WEST Katni S.S.E.C.N. RIPERING OF 10 454 1 >=500 RAILWAY KATNI WEST RAILWAY MALGADI DEEBBE KATNI Nill 483501 16 44 Jhiriya U.G.Koyla Dumarkachar Jhiriya CAOL SUPPLY WORK 06 239 4 >=500 khadan U.G.Koyla khadan Dumarkachar 484446 17 23 CENTURY YARN SATRATI 451228 CENTURY YARN 06 141 4 >=500 18 21 ret spean pithampur 454775 DHAGA PRODUCTS 06 131 4 >=500 19 21 hdfe FEBRICATION PITHAMPUR 454775 FEBRICATION 06 141 2 >=500 20 29 INSUTATOR ILE. -

Temples of India

TEMPLES OF INDIA A SELECT ANNOTATED BIBLIOCRAPHY SUBMITTED !N PARTIAL FULFILMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF iHagter of librarp Science 1989-90 BY ^SIF FAREED SIDDIQUI Roll. No. 11 Enrolment. No. T - 8811 Under the Supervision of MR. S. MUSTAFA K. Q. ZAIDI Lecturer DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIIVi UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 1990 /> DS2387 CHECKED-2002 Tel t 29039 DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY SCIENCE AUGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH 202001 (India) September 9, 1990 This is to certify that the PI* Lib* Science dissertation of ^r* Asif Fareed Siddiqui on ** Temples of India t A select annotated bibliography " was compiled under my supervision and guidance* ( S. nustafa KQ Zaidi ) LECTURER Dedicated to my Loving Parents Who have always been a source of Inspiration to me CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENT i - ii LISTS OF PERIODICALS iii - v PART-I INTRODUCTION 1-44 PART-II ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY 45 - 214 PART-III INDEX 215 - 256 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and supervisor Mr. S.Mustafa K.Q. Zaidi, Lecturer, Department of Library Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh who inspite of his many pre-occupation spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step during the course of this study. His deep and critical understanding of the problem helped me a lot in compiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to Professor Mohd. Sabir Husain, Chairman, Department of Library Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh for his able guidance and suggestions whenever needed. I am also highly indebted to Mr. Almuzaffar Khan,Reader, Department of Library Science, Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh whose invaluable guidance and suggestions were always available to me.