Phantom Bodies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2009 The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival Benjamin R. Cox III [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Recommended Citation Cox, Benjamin R. III, "The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival" (2009). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 31. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/31 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Benjamin R. Cox, III April, 2009 Mentor: Dr. J. Thomas Cook Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Winter Park, Florida This project is dedicated to Nathan Jablonski and Richard S. Smith Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 The Science of Mediumship.................................................................... 11 The Case of Leonora E. Piper ................................................................ 33 The Case of Eusapia Palladino............................................................... 45 My Personal Experience as a Seance Medium Specializing -

THE MEDIUMSHIP of ARNOLD CLARE Leader of the Trinity of Spiritual Fellowship

THE MEDIUMSHIP OF ARNOLD CLARE Leader of the Trinity of Spiritual Fellowship by HARRY EDWARDS Captain, Indian Army Reserve of Officers. Lieutenant, Home Guard. Parliamentary Candidate North Camberwell 1929 and North-West Camberwell 1936. London County Council Candidate 1928, 1931, 1934, 1937. Leader of the Balham Psychic Research Society. Author of ‘The Mediumship of Jack Webber’ First Published by: THE PSYCHIC BOOK CLUB 144 High Holborn, London, W.C. 1 FOREWORD Apart from the report by Mr. W. Harrison of the early development of Mr. Arnold Clare's mediumship, the descriptions of the séances, the revelations of Peter and the writing of this book took place during the war years 1940-41. As enemy action on London intensified, the physical séances ceased and in the autumn of 1940 were replaced by discussion circles. The first few circles took place in the author's house before a company of about twenty people. It was soon appreciated that the intelligence (known as Peter), speaking through the entranced medium, was of a high order and worthy of reporting. So these large discussion groups gave way to a small circle held in the medium's house, attended by Mr. and Mrs. Clare, Mr. and Mrs. Hart, Mrs. Edwards and the author, an occasional visitor and with Mrs. W. B. Cleveland as stenographer. The procedure at these circles would be that, in normal white light, Mr. Clare would enter into a trance state. His Guide, Peter, taking control, would discourse upon the selected topic answering all questions fluently and without hesitation. Frequently, during these sittings, the air-raid sirens would be heard and the local anti- aircraft guns would be in action. -

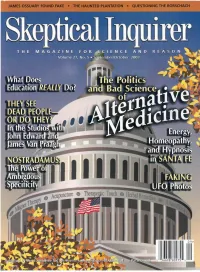

Issue-05-9.Pdf

THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION of Claims of the Paranormal AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO| • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist York Univ., Toronto Saul Green. PhD, biochemist president of ZOL James E- Oberg, science writer Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, Consultants, New York. NY Irmgard Oepen, professor of medicine (retired). Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts Marburg, Germany Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor-in-chief, New and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, University Loren Pankratz. psychologist. Oregon Health England Journal of Medicine of Miami Sciences Univ. Robert A. Baker, psychologist. Univ. of Kentucky C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist. Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, Al Hibbs, scientist, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist. MIT consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Massimo Polidoro. science writer, author, execu Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist. Simon Fraser understanding and cognitive science, tive director CICAP, Italy Univ., Vancouver, B.C.. Canada Indiana Univ. Milton Rosenberg, psychologist Univ. of Chicago Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics Wallace Sampson. M.D.. clinical professor of medi California and professor of history of science, Harvard Univ. cine. Stanford Univ.. editor, Scientific Review of Susan Blackmore, Visiting Lecturer, Univ. of the Ray Hyman,' psychologist. -

Glossary of Spiritualist Terms and Techniques

A PPENDIX A Glossary of Spiritualist Terms and Techniques automatic writing. A Spirit uses the medium’s hand to write replies to any number of questions posed; also practiced by amateurs as a way of strengthening their spiritual powers. As an added feature, a magic pencil sometimes floats. In such instances, the Spirits are asking the medium to begin writing. How it is done: The pencil hangs on thin metal or glass wires. clairgustance or clairlience. A taste or smell associated with the Spirit. For example, if you are trying to contact your mother, who was fond of gardening, a waft of rose water might be introduced. How it is done: aromatherapy. dermography, also known as skin writing. The Spirits literally write words or pictures on the medium’s flesh. How it is done: Invisible ink, likely lemon juice, is used. When held up to a candle, the ink grows increasingly visible. ectoplasm. A pale, filmy materialization of the soul, produced by the medium when in a trance state. Likely invented by Leah Fox (circa 1860). The last manifestation of ectoplasm seems to have taken place in 1939. Cambridge University has a sample; it looks and feels like cheesecloth or chiffon. Female mediums sometimes stuffed ectoplasm in their vaginas, necessitating strip- searches. See also soul and Spirit’s progress. lampadomancy. Flame reading. The messages might be conveyed by changes in flame intensity, color, or direction. How it is done: Chemicals can be added to a segment of the candle to make the flame flicker or change color. On the direction of the flame: a small hole in the table may allow 164 Glossary of Spiritualist Terms and Techniques for a flue to affect air- current. -

Psychic News Magazine

£3.80 | AUGUST 2015 ISSUE NO 4130 ‘I SEE DEAD PEOPLE’ SAYS WIN TOP-SELLING NOVELIST A ONE-TO-ONE SANTA MONTEFIORE SKYPE READING WITH JAMES VAN PRAAGH HOW TO CULTIVATE CLAIRVOYANCE AIR CHIEF BY SCRYING MARSHAL LORD DOWDING: THE PHOTOGRAPHS SPIRITUALIST OF THE DEAD? WHO SAVED CLASSSIC SPIRIT BRITAIN IMAGES UNDER SCRUTINY HEALER’S ‘SECRET’ ROYAL MEMOS CALL FOR SPIRIT GUIDE HOMEOPATHY ISSUES FUNDING CHALLENGE KERRY KATONA 08> CALLS IN TEAM OF EXORCISTS 9 770033 280014 FEATURE art viewed from both sides of the vEIL Photo: ©Sylvain Deleu TWO art exhibitions, one in London and the other in San London’s College of Psychic Studies, of Francisco, have had visitors contemplating the afterlife from which the artist is a member, to help bring them back to Earth. very different angles. On loan were some rare spirit Entering Karen Mirza’s first solo exhibition Phyllis Mirza – but to open up a much photographs, séance notes from the visit at fig-2, in the ICA Studio on London’s broader dialogue with those who view her to the College made by Scottish physical prestigious Mall, just a short royal carriage work. medium Helen Duncan, and the original journey down the road to Buckingham editions of two controversial books, Art Palace, was like stepping into a physical The idea, she explains, was to “bring forth Magic and Ghostland, edited by medium séance. a confluence of occult and radical politics” Emma Hardinge Britten. There was even that is a further step in experimenting with an original copy of Psychic News (dated The room was bathed in red light and her ongoing exploration of “positions that April 1, 1944) reporting on Helen Duncan’s among the exhibits was a huge image concentrate on women, bodies and sites of trial at the Old Bailey. -

A Closer Look Compiled by Production Dramaturg Charlotte Stephens

A Closer Look Compiled by production dramaturg Charlotte Stephens Ghost-Writer: A Closer Look 1 Presented by the Commonweal Theatre Company September 7 - November 12, 2017 by Michael Hollinger Essentials The Plot It is 1919, somewhere in New York City, recounts come to life before us, giving us in an office with a view of the Queensboro glimpses into the past. We witness her first Bridge over the East River. Myra Babbage is meeting with Woolsey, see them working speaking to an unseen and unheard interview- together on his novels; we see also her first er, the intent and purpose of whom we glean meeting with Woolsey’s wife, Vivian, and gradually from her one-sided conversation sense, with Myra, the jealous suspicion with with him. Myra believes the interviewer has which she regards her husband’s typists. been sent by the wife of her late employer, As Myra’s narration (and our witness) the deceased novelist of past events con- Franklin Woolsey, for tinues to unfold, we whom she was typ- learn more about the ist over the course of relationships among many years. the three characters. Through Myra’s Vivian, wary of this narrative to the inter- new typist, had at one viewer, we learn that time engaged Myra she has been continu- as a typing instruc- ing to type the novel tor—presumably so which Woolsey had that she might take left unfinished when over the work and he died, some weeks render Myra’s service earlier. She believes the unnecessary. Through- words are Woolsey’s out, Myra maintains but she denies any Typewriters dominated industry and commerce for over a century. -

Medicine and the Paranormal in Gravity's Rainbow

Medicine and the Paranormal in Gravity’s Rainbow: Ephyre, Anaphylaxis, and That Charles Richet Terry Reilly and Steve Tomaske Je n’ai jamais dit que c’était possible. J’ai dit que c’était seulement vrai. I never said it was possible. I only said it was true. —Charles Richet Since Lawrence Wolfley’s 1977 article “Repression’s Rainbow: The Presence of Norman O. Brown in Pynchon’s Big Novel,” commentators on Pynchon’s writing have often found themselves in uncomfortable and sometimes ridiculous positions where they are forced to argue about the importance of something although or because it is not explicitly in Pynchon’s text. Using various forms of logic, they find themselves “seeking other orders behind the visible” (GR 188),1 often concluding that something’s present because it’s absent. This paper, which proudly follows in that tradition, is divided into four short parts: the first part is a brief biography of Charles Richet; the second surveys his interests in the paranormal and psychic phenomena, emphasizing what we think are echoes in Gravity’s Rainbow; the third discusses his work on anaphylaxis, particularly as it relates to Gravity’s Rainbow; and in the fourth, we will try to connect the pieces and explain why Richet is, to our minds, perhaps one of the most important historical figures not mentioned in Gravity’s Rainbow. 1. Richet’s Biography Charles Richet was born in 1850 and died in 1935. A Parisian physiologist and student of the occult and paranormal, Richet is best known as the winner of the 1913 Nobel Prize in Medicine for his discovery of anaphylaxis and anaphylactic shock.2 Richet, originally trained in the emerging new field of psychology, revived the study of hypnotism (which was falling into disrepute by 1875) and convinced Jean-Martin Charcot, Pierre Janet and later, Sigmund Freud, of its value in psychotherapy (Boadella, 46, Wolf 26- 28). -

The History Spiritualism

THE HISTORY of SPIRITUALISM by ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE, M.D., LL.D. former President d'Honneur de la Fédération Spirite Internationale, President of the London Spiritualist Alliance, and President of the British College of Psychic Science Volume Two With Eight Plates Sir Arthur Conon Doyle CHAPTER I THE CAREER OF EUSAPIA PALLADINO The mediumship of Eusapia Palladino marks an important stage in the history of psychical research, because she was the first medium for physical phenomena to be examined by a large number of eminent men of science. The chief manifestations that occurred with her were the movement of objects without contact, the levitation of a table and other objects, the levitation of the medium, the appearance of materialized hands and faces, lights, and the playing of musical instruments without human contact. All these phenomena took place, as we have seen, at a much earlier date with the medium D. D. Home, but when Sir William Crookes invited his scientific brethren to come and examine them they declined. Now for the first time these strange facts were the subject of prolonged investigation by men of European reputation. Needless to say, these experimenters were at first sceptical in the highest degree, and so-called ‘tests’ (those often silly precautions which may defeat the very object aimed at) were the order of the day. No medium in the whole world has been more rigidly tested than this one, and since she was able to convince the vast majority of her sitters, it is clear that her mediumship was of no ordinary type. -

Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become a Science Creative Works

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become A Science Creative Works 2021 Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become A Science John Haller Jr Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/histcw_ms Copyright © 2020, John S. Haller, Jr. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN (print): 9798651505449 Interior design by booknook.biz This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Creative Works at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become A Science by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Modern Spiritualism: Its Quest to Become A Science By John S. Haller, Jr. Copyright © 2020, John S. Haller, Jr. All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. ISBN (print): 9798651505449 Interior design by booknook.biz Spiritualism, then, is a science, by authority of self-evident truth, observed fact, and inevitable deduction, having within itself all the elements upon which any science can found a claim. (R. T. Hallock, The Road to Spiritualism, 1858) TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Chapters 1. Awakening 11 2. Rappings 41 3. Poughkeepsie Seer 69 4. Architect of the Spirit World 95 5. Esoteric Wisdom 121 6. American Portraits 153 7. -

Mediums and Psychics

Bumps in the Night!!!! December 2013 Issue Paranormal “U” Medium / Psychics By Marcie Clarke, TnT Paranormal Investigators LLC Many people are confused when it comes to paranormal terminology. As you can see by the below reference, there are profound differences between these things, yet all are lumped under the paranormal umbrella. “Psychic - pertaining to mental forces, telepathy, extra sensory perception Medium - contacting and being able to communicate with spirits of those that have passed Clairvoyance - the ability to see things beyond our normal senses”) The word psychic, used for the first time by Camille Flammarion, a French astronomer and spiritualist, comes from the Greek work psychoikis meaning “of the mind” . Psychics, known as fortune-tellers in ancient times, used astrology and elaborate systems to perform their work. Fortune-tellers believed the position of the stars would allow them to see into others’ lives and be able to see their future. Others that didn’t use astrology and elaborate systems to see the future were known as seers or prophets. These individuals later became known as clairvoyants. In early times, seers were usually priests, judges or advisors. One of the most notable published prophets of his time was Michael de Nostredame or Nostredamus. Nostredamus’ prophecies are world famous and rarely out of print. Although he has been called controversial, he has been credited with predicting numerous events around the world. In the mid-nineteenth century spiritualism became popular in the United States and it was believed that with the help of a medium one could contact the dead. In the Victorian period, a gentleman by the name of Daniel Dunglas Home became famous for his ability to speak to the dead. -

Ghost Hunters

INVESTIGATIVE FILES Ghost Hunters elief that spirits of the dead exist and can appear to the living is Bboth ancient and widespread, yet the actual study of ghostly phenomena has largely been lacking. So-called “inves- tigation” has ranged from mere collecting of ghost tales to the use of “psychic” impressions to a pseudoscientific reliance on technology applied in a questionable fashion. Real science has largely been ignored. Collecting Tales What passed for investigation in earlier times is illustrated by a “true” ghost story related by Pliny the Younger (ca. 100 a.d.). It has been “regarded as the first investigated ghost story” (Finucane 2001). A hearsay tale, already a century old when Figure 1. Paranormal investigator Vaughn Rees mimics ghost hunters, demonstrating how not to find a ghost. Pliny told it, it involved a house in Athens (Photo courtesy of Vaughn Rees.) haunted by the specter of an emaciated, Victoria’s reign represent not beings of a slamming door might have been caused fettered man. It rattled its chains at night that other world, but of this. and brought disease and death to visitors. by a draft or may have been a prank). Undaunted, however, a stoic philosopher Even in a given era, ghosts seem to Uncritical collections of ghost tales— named Atheno dorus bought the house, behave according to individual expecta- rife with weaselly phrases like “is said tried first to ignore the beckoning phan- tions, being as likely to walk through a to be” and “some believe that” (e.g., tom, then calmly followed it into the wall as to knock on a door before entering Hauck 1996, 1, 12)—are ubiquitous. -

Dionysius Areopagites: a Christian Mysticism?

Hieromonk Alexander (Golitzin) Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA DIONYSIUS AREOPAGITES: A CHRISTIAN MYSTICISM? I. Introduction: A Controversial Figure The mysterious author who wrote under the name of Dionysius the Are- opagite sometime around the turn of the sixth century has been the subject of theological and scholarly controversy for half a millenium.1 With a few re- cent exceptions, this controversy has been limited to the Christian West. It began properly with Martin Luther’s explicit dismissal of «Dionysius» (whom henceforth I shall refer to without the inverted commas) as plus platonizans quam christianizans, «more a Platonist than a Christian», and his warning to «stay away from that Dionysius, whoever he was!» I am myself expert in neither the Reformation generally nor Luther in particular, but I think it not inaccurate to say that he read Dionysius as perhaps the advocate par excel- lence of a theologia gloriae, which is to say, a theological perspective which effectively makes superfluous the Incarnation and atoning death of God the Word, and which does so because it assumes that the human mind of itself is capable, at least in potential, of achieving direct contact with the deity. The great doctor of the Reform saw this pernicious attitude, so in opposition to his own theologia crucis, as especially embodied in the little Dionysian trea- tise, The Mystical Theology, which he read as an example less of truly Chris- tian piety than of an appeal to the autonomous human intellect, hence: «Shun like the plague that Mystical Theology and other such works!» Ever since Luther, though here I should add that I am over-simplifying somewhat, Di- onysius has been by and large a «non-starter» for Protestant theology and devotion, while Protestant scholarship, in so far as it deals with him at all, remains generally — or even emphatically — unsympathetic.2 1 I will be referring to the Greek text of Dionysius in two editions, PG 3, with the column numbers, and, in parenthesis, the page and line numbers of the recent critical edition: Corpus Dionysiacum.