Glossary of Spiritualist Terms and Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Automatic Writing and the Book of Mormon: an Update

ARTICLES AND ESSAYS AUTOMATIC WRITING AND THE BOOK OF MORMON: AN UPDATE Brian C. Hales At a Church conference in 1831, Hyrum Smith invited his brother to explain how the Book of Mormon originated. Joseph declined, saying: “It was not intended to tell the world all the particulars of the coming forth of the Book of Mormon.”1 His pat answer—which he repeated on several occasions—was simply that it came “by the gift and power of God.”2 Attributing the Book of Mormon’s origin to supernatural forces has worked well for Joseph Smith’s believers, then as well as now, but not so well for critics who seem certain natural abilities were responsible. For over 180 years, several secular theories have been advanced as explanations.3 The more popular hypotheses include plagiarism (of the Solomon Spaulding manuscript),4 collaboration (with Oliver Cowdery, Sidney Rigdon, etc.),5 1. Donald Q. Cannon and Lyndon W. Cook, eds., Far West Record: Minutes of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1830–1844 (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1983), 23. 2. “Journal, 1835–1836,” in Journals, Volume. 1: 1832–1839, edited by Dean C. Jessee, Mark Ashurst-McGee, and Richard L. Jensen, vol. 1 of the Journals series of The Joseph Smith Papers, edited by Dean C. Jessee, Ronald K. Esplin, and Richard Lyman Bushman (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2008), 89; “History of Joseph Smith,” Times and Seasons 5, Mar. 1, 1842, 707. 3. See Brian C. Hales, “Naturalistic Explanations of the Origin of the Book of Mormon: A Longitudinal Study,” BYU Studies 58, no. -

Psychic Phenomena and the Mind–Body Problem: Historical Notes on a Neglected Conceptual Tradition

Chapter 3 Psychic Phenomena and the Mind–Body Problem: Historical Notes on a Neglected Conceptual Tradition Carlos S. Alvarado Abstract Although there is a long tradition of philosophical and historical discussions of the mind–body problem, most of them make no mention of psychic phenomena as having implications for such an issue. This chapter is an overview of selected writings published in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries literatures of mesmerism, spiritualism, and psychical research whose authors have discussed apparitions, telepathy, clairvoyance, out-of-body experiences, and other parapsy- chological phenomena as evidence for the existence of a principle separate from the body and responsible for consciousness. Some writers discussed here include indi- viduals from different time periods. Among them are John Beloff, J.C. Colquhoun, Carl du Prel, Camille Flammarion, J.H. Jung-Stilling, Frederic W.H. Myers, and J.B. Rhine. Rather than defend the validity of their position, my purpose is to docu- ment the existence of an intellectual and conceptual tradition that has been neglected by philosophers and others in their discussions of the mind–body problem and aspects of its history. “The paramount importance of psychical research lies in its demonstration of the fact that the physical plane is not the whole of Nature” English physicist William F. Barrett ( 1918 , p. 179) 3.1 Introduction In his book Body and Mind , the British psychologist William McDougall (1871–1938) referred to the “psychophysical-problem” as “the problem of the rela- tion between body and mind” (McDougall 1911 , p. vii). Echoing many before him, C. S. Alvarado , PhD (*) Atlantic University , 215 67th Street , Virginia Beach , VA 23451 , USA e-mail: [email protected] A. -

The Heritage of Non-Theistic Belief in China

The Heritage of Non-theistic Belief in China Joseph A. Adler Kenyon College Presented to the international conference, "Toward a Reasonable World: The Heritage of Western Humanism, Skepticism, and Freethought" (San Diego, September 2011) Naturalism and humanism have long histories in China, side-by-side with a long history of theistic belief. In this paper I will first sketch the early naturalistic and humanistic traditions in Chinese thought. I will then focus on the synthesis of these perspectives in Neo-Confucian religious thought. I will argue that these forms of non-theistic belief should be considered aspects of Chinese religion, not a separate realm of philosophy. Confucianism, in other words, is a fully religious humanism, not a "secular humanism." The religion of China has traditionally been characterized as having three major strands, the "three religions" (literally "three teachings" or san jiao) of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Buddhism, of course, originated in India in the 5th century BCE and first began to take root in China in the 1st century CE, so in terms of early Chinese thought it is something of a latecomer. Confucianism and Daoism began to take shape between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. But these traditions developed in the context of Chinese "popular religion" (also called folk religion or local religion), which may be considered a fourth strand of Chinese religion. And until the early 20th century there was yet a fifth: state religion, or the "state cult," which had close relations very early with both Daoism and Confucianism, but after the 2nd century BCE became associated primarily (but loosely) with Confucianism. -

Reader's Companion to John Cowper Powys's a Glastonbury Romance

John Cowper Powys’s A Glastonbury Romance: A Reader’s Companion Updated and Expanded Edition W. J. Keith December 2010 . “Reader’s Companions” by Prof. W.J. Keith to other Powys works are available at: https://www.powys-society.org/Articles.html Preface The aim of this list is to provide background information that will enrich a reading of Powys’s novel/ romance. It glosses biblical, literary and other allusions, identifies quotations, explains geographical and historical references, and offers any commentary that may throw light on the more complex aspects of the text. Biblical citations are from the Authorized (King James) Version. (When any quotation is involved, the passage is listed under the first word even if it is “a” or “the”.) References are to the first edition of A Glastonbury Romance, but I follow G. Wilson Knight’s admirable example in including the equivalent page-numbers of the 1955 Macdonald edition (which are also those of the 1975 Picador edition), here in square brackets. Cuts were made in the latter edition, mainly in the “Wookey Hole” chapter as a result of the libel action of 1934. References to JCP’s works published in his lifetime are not listed in “Works Cited” but are also to first editions (see the Powys Society’s Checklist) or to reprints reproducing the original pagination, with the following exceptions: Wolf Solent (London: Macdonald, 1961), Weymouth Sands (London: Macdonald, 1963), Maiden Castle (ed. Ian Hughes. Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 1990), Psychoanalysis and Morality (London: Village Press, 1975), The Owl, the Duck and – Miss Rowe! Miss Rowe! (London: Village Press, 1975), and A Philosophy of Solitude, in which the first English edition is used. -

PSYPIONEER JOURNAL Volume 7, No 11: November 2011

PSYPIONEERF JOURNAL Founded by Leslie Price Edited by Archived by Paul J. Gaunt Garth Willey EST 2004 VolumeAmalgamation 7, No 11: of NovemberSocieties 2011 Discontinued; a Forgotten Spiritualist Tragedy – Leslie Price 338 Includes: A New Attack by Father Thurston – Psychic News Spiritualism and Suicide - The Tablet All of them are Evil Spirits! – Psychic News The Physical Phenomena of the Past, An Historical Survey – Leslie Curnow 349 Mrs. Mary Marshall – Paul J. Gaunt 355 Anti-Spiritualist Studies – Leslie Price 363 The Beginnings of Full Form Materialisations in England Catherine (Kate) Elizabeth Wood 1854-1884 – continued 366 Some books we have reviewed 374 How to obtain this Journal by email 375 ============================ 337 DISCONTINUED; A FORGOTTEN SPIRITUALIST TRAGEDY Serious students of the pioneers know that the on-line catalogues of major libraries are a treasure trove of information, often revealing unknown material. Sometimes, however, there is a dramatic story behind the catalogue card. So it is with an item in the subsidiary catalogue of British Library newspapers. One of them Spiritual Truth is marked “discontinued”. Behind this word “discontinued” is a tragedy, into which the American medium Arthur Ford, the editor of the then recently launched (1932) Psychic News Maurice Barbanell, and the Jesuit researcher Herbert Thurston were to be drawn. Spiritual Truth was edited by Percival Beddow, a prominent figure in Christian Spiritualism. He was, for example, one of the first to attend a Zodiac circle, and was addressed by Zodiac.1 Beddow also published a script from Philip the Evangelist, on which Sir Arthur Conan Doyle commented in his History of Spiritualism: “Two long scripts have recently appeared which have been written by the hand of the semi- conscious medium, Miss Cummins, the writing coming through at the extraordinary pace of 2,000 words per hour. -

The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2009 The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival Benjamin R. Cox III [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Recommended Citation Cox, Benjamin R. III, "The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival" (2009). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 31. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/31 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Benjamin R. Cox, III April, 2009 Mentor: Dr. J. Thomas Cook Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Winter Park, Florida This project is dedicated to Nathan Jablonski and Richard S. Smith Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 The Science of Mediumship.................................................................... 11 The Case of Leonora E. Piper ................................................................ 33 The Case of Eusapia Palladino............................................................... 45 My Personal Experience as a Seance Medium Specializing -

Henry Handel Richardson, a Secret Life – by Dr Barbara Finlayson

Henry Handel Richardson, a Secret Life – a talk given by Dr Barbara Finlayson at the Bendigo Philosopher’s Group on July 2, 2018 The background music are songs to which Henry Handel Richardson (HHR mainly from now on) wrote the music, some whilst she was at school, others as a music student at Leipzig. That she wrote music is not well known as was her deep involvement in Spiritualism, the subject of my talk. Firstly though, I shall give a very, very, potted summary about this author Henry Handel Richardson, the nom de plume of Ethel Florence Lindesay Richardson. She was born on the 3rd January 1870 in East Melbourne, the eldest daughter of Dr Walter Richardson and his wife Mary. The family lived in various Victorian towns, as well as Melbourne itself during HHR’s childhood and youth. These included Chiltern, Queenscliff, Koroit, and Maldon after her father’s death. Her mother took the family to Europe in 1888 to enable HHR and her sister Lill to continue her musical studies at the Leipzig Conservatorium. HHR married George Robertson who became chair at the University of London and they moved to that city 1903. She published her first novel, Maurice Guest in 1908 and that is when she adopted her pseudonym. (I have included a list of her writing in the hand out.) The best known are The Getting of Wisdom and The Fortunes of Richard Mahony. She died in 1946, aged 76. In Dorothy Green’s book about Henry Handel Richardson, Ulysses Bound, she said, ‘Richardson’s life-long adherence to Spiritualism is a fact which has largely been ignored.’ This book was first published in 1973, and HHR’s involvement in Spiritualism was largely ignored until 1996 when 2 events occurred. -

Formato Articulo

ISSN 0719-4285 FRONTERAS – Revista de Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades http://publicacionescienciassociales.ufro.cl/index.php/fronteras/index doi: (en proceso) Contacting dead people online: The hidden Victorian rationality behind using The Internet for paranormal activities. Contactando a los muertos en línea: la racionalidad victoriana oculta tras el uso de Internet para realizar actividades paranormales. DR. DAVID RAMÍREZ PLASCENCIA. Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, México. [email protected] Recibido el 25 de junio de 2015 Aceptado el 1 de diciembre de 2015 FRONTERAS VOL II NÚM. 2 · DICIEMBRE 2015 · ISSN 0719-4285 · PÁGS. 89 -103 91 DAVID RAMÍREZ RESUMEN The aim of this article is to find the rational foundations behind the belief in the paranormal, and to understand why some people still believe that it is possible to use scientific devices like computers or smart phones to contact dead people. This is especially interesting, because in this case we are dealing with the fact the same way as in the Victorian age, people use technical advances to reinforce their convictions on the existence of life beyond life. In this sense one important task is to realize the role of technological gears in supporting this kind of shared rationality. Unexpectedly, science has not undermined supernatural thought but it has served for reinforcing it. It looks like the more advanced the civilization the more possibilities it turns into the search of alternative and extravagant conceptions of the world. Key Words: Media, Victorians, Internet, the paranormal, folklore. ABSTRACT El objetivo de este artículo es encontrar el soporte racional que subyace bajo la creencia en lo paranormal, y comprender porque algunas personas creen que es posible utilizar dispositivos tecnológicos como computadoras o teléfonos inteligentes para contactar a los muertos. -

THE GOSPEL According to Spiritism

THE GOSPEL According to Spiritism Allan Kardec THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO SPIRITISM Contains explanations of the moral maxims of Christ in accordance with Spiritism and their application in various circumstances in life. by ALLAN KARDEC Author of THE SPIRITS’ BOOK Unshakable faith is only that which can meet reason face to face in every Human epoch. ____________ This English translation is taken from the 3rd edition of the original French, as being the one containing all of Allan Kardec’s final revisions, published in 1866. L’ÉVANGILE SELON LE SPIRITISME CONTENANT L’EXPLICATION DES MAXIMES MORALES DU CHRIST LEUR CONCORDANCE AVEC LE SPIRITISME ET LEUR APPLICATION AUX DIVERSES POSITIONS DE LA VIE PAR ALLAN KARDEC Auteur du Livre des Esprits. Il n’y a de foi inébranlable que celle qui peut regarder la raison face à face, à tous les àges de l’humanité. _____________ T R O I S I È M E É D I T I O N REVUÉ, CORRIGÉE ET MODIFIÉE. _______________ P A R I S LES ÉDITEURS DU LIVRE DES ESPRITS 35, QUAI DES AUGUSTINS DENTU, FRÉD, HENRI, libraires, au Palais-Royal Et au bureau de la REVUE SPIRITE, 59, rue et passage Saint-Anne 1866 Réserve de tous droits. (Facsimile of original) Original title ‘L’Évangile Selon le Spiritisme’ first published in France, 1864. 1st Edition of this translation 1987 TRANSLATORS COPYRIGHT © J. A. Duncan, 1987 All rights reserved. ISBN 947823 09 3 Cover design by Helen Ann Blair Typesetting and Artwork by Mainline Typesetting Services Unit 2, Millside Industrial Estate, Southmill Road, Bishop’s Stortford, Herts. -

Historical Perspective

Journal of Scientific Exploration, Vol. 34, No. 4, pp. 717–754, 2020 0892-3310/20 HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE Early Psychical Research Reference Works: Remarks on Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science Carlos S. Alvarado [email protected] Submitted March 11, 2020; Accepted July 5, 2020; Published December 15, 2020 DOI: 10.31275/20201785 Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC Abstract—Some early reference works about psychic phenomena have included bibliographies, dictionaries, encyclopedias, and general over- view books. A particularly useful one, and the focus of the present article, is Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934). The encyclopedia has more than 900 alphabetically arranged entries. These cover such phenomena as apparitions, auras, automatic writing, clairvoyance, hauntings, materialization, poltergeists, premoni- tions, psychometry, and telepathy, but also mediums and psychics, re- searchers and writers, magazines and journals, organizations, theoretical ideas, and other topics. In addition to the content of this work, and some information about its author, it is argued that the Encyclopaedia is a good reference work for the study of developments from before 1933, even though it has some omissions and bibliographical problems. Keywords: Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science; Nandor Fodor; psychical re- search reference works; history of psychical research INTRODUCTION The work discussed in this article, Nandor Fodor’s Encyclopaedia of Psychic Science (Fodor, n.d., circa 1933 or 1934), is a unique compilation of information about psychical research and related topics up to around 1933. Widely used by writers interested in overviews of the literature, Fodor’s work is part of a reference literature developed over the years to facilitate the acquisition of knowledge about the early publications of the field by students of psychic phenomena. -

THE MEDIUMSHIP of ARNOLD CLARE Leader of the Trinity of Spiritual Fellowship

THE MEDIUMSHIP OF ARNOLD CLARE Leader of the Trinity of Spiritual Fellowship by HARRY EDWARDS Captain, Indian Army Reserve of Officers. Lieutenant, Home Guard. Parliamentary Candidate North Camberwell 1929 and North-West Camberwell 1936. London County Council Candidate 1928, 1931, 1934, 1937. Leader of the Balham Psychic Research Society. Author of ‘The Mediumship of Jack Webber’ First Published by: THE PSYCHIC BOOK CLUB 144 High Holborn, London, W.C. 1 FOREWORD Apart from the report by Mr. W. Harrison of the early development of Mr. Arnold Clare's mediumship, the descriptions of the séances, the revelations of Peter and the writing of this book took place during the war years 1940-41. As enemy action on London intensified, the physical séances ceased and in the autumn of 1940 were replaced by discussion circles. The first few circles took place in the author's house before a company of about twenty people. It was soon appreciated that the intelligence (known as Peter), speaking through the entranced medium, was of a high order and worthy of reporting. So these large discussion groups gave way to a small circle held in the medium's house, attended by Mr. and Mrs. Clare, Mr. and Mrs. Hart, Mrs. Edwards and the author, an occasional visitor and with Mrs. W. B. Cleveland as stenographer. The procedure at these circles would be that, in normal white light, Mr. Clare would enter into a trance state. His Guide, Peter, taking control, would discourse upon the selected topic answering all questions fluently and without hesitation. Frequently, during these sittings, the air-raid sirens would be heard and the local anti- aircraft guns would be in action. -

Issue-05-9.Pdf

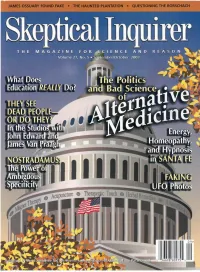

THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION of Claims of the Paranormal AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO| • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist York Univ., Toronto Saul Green. PhD, biochemist president of ZOL James E- Oberg, science writer Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, Consultants, New York. NY Irmgard Oepen, professor of medicine (retired). Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts Marburg, Germany Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor-in-chief, New and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, University Loren Pankratz. psychologist. Oregon Health England Journal of Medicine of Miami Sciences Univ. Robert A. Baker, psychologist. Univ. of Kentucky C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist. Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, Al Hibbs, scientist, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist. MIT consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Massimo Polidoro. science writer, author, execu Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist. Simon Fraser understanding and cognitive science, tive director CICAP, Italy Univ., Vancouver, B.C.. Canada Indiana Univ. Milton Rosenberg, psychologist Univ. of Chicago Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics Wallace Sampson. M.D.. clinical professor of medi California and professor of history of science, Harvard Univ. cine. Stanford Univ.. editor, Scientific Review of Susan Blackmore, Visiting Lecturer, Univ. of the Ray Hyman,' psychologist.