Augustine Responds to the Editor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Working with the Soul in Counselling and Supervision Practice

Insights from Neurobiology to (the) (S)oul Peter Bowes MBE BSc BD Dmin BACP Senior Accredited Counsellor and Supervisor BACP Cardiff November 2017 My experience and yours is interpreted and modulated by our brain/Mind. Before using our experience to derive natural history, To communicate theology, psychology, our experience the philosophy, perhaps we should understand more of brain appears to significance of relationship of brain and mind to construct myth experiences and metaphor and For example, we cannot understand spirituality we benefit from without understanding brain ritual and mind and vice versa Insights from Neurobiology to soul In the beginning In the beginning….. Mithen, Stephen, The Prehistory of the Mind: A search for the origins of art, religion and science. Thames and Hudson, London, 1996. Lewis-Williams, David, The Mind in the Cave, Consciousness and the Origins of Art, Thames and Hudson, 2002 http://lecerveau.mcgill.ca/flash/i/i_12/i_12_s/i_12_s_con/i_12_s_con.html Act one 6-4.5 million years ago . A long time of little action to be viewed in total darkness 4.5 – 1.8 million years ago . lit only by a flickering candle life begins in Africa then develops with a rush of actors with Act two tools for killing or savaging 1.8 million to 100,00o years ago . Lighting still poor but brightens towards the end . Homo erectus appears whose presence spreads widely including Europe and with more impressive hand axes Act three . Neanderthals appear who develop and hunt game with stone tools maybe some of bone but no carvings; brain size reaches modern dimensions With acknowledgements to Steven Mithen, Prehistory of the Mind Act four 100,000 years to present day . -

A Brief History of the “Sursem” Project

EDGESCIENCE #22 • JUNE 2015 / 3 ❛THE OBSERVATORY❜ Edward F. Kelly Toward Reconciliation of Science and Spirituality: A Brief History of the “Sursem” Project of mind and consciousness are generated by (or in some mys- terious way identical with, or supervenient upon), neurophysi- ological processes occurring in the brain. We are “meat com- puters” in Marvin Minsky’s chilling phrase, or “moist robots” in its Dilbert parody. Mental causation, free will, and the self are mere illusions, by-products of the grinding of our neu- ral machinery. And of course since mind and personality are entirely products of our bodily machinery, they are necessarily extinguished, totally and finally, by the demise and dissolution of the body. There can be no doubt that this bleak vision continues to dominate mainstream scientific thinking and has contributed to the “disenchantment” of the modern world with its multi- farious ills. It has also driven progressive erosion of traditional forms of religious belief. Indeed, recent years have witnessed a series of all-out attacks on religion by well-meaning defenders of Enlightenment-style rationalism such as Richard Dawkins and Daniel Dennett, who clearly regard themselves and cur- rent mainstream science as reliably marshaling the intellectual virtues of reason and objectivity against retreating forces of irrational authority and superstition. For them the truth of physicalism has been demonstrated beyond reasonable doubt, and to think anything different is necessarily to abandon cen- turies of scientific progress, unleash the black flood of occult- ism, and revert to primitive supernaturalist beliefs characteristic of bygone times. Daniel Bianchetta Not everyone shares these sentiments. -

The Heritage of Non-Theistic Belief in China

The Heritage of Non-theistic Belief in China Joseph A. Adler Kenyon College Presented to the international conference, "Toward a Reasonable World: The Heritage of Western Humanism, Skepticism, and Freethought" (San Diego, September 2011) Naturalism and humanism have long histories in China, side-by-side with a long history of theistic belief. In this paper I will first sketch the early naturalistic and humanistic traditions in Chinese thought. I will then focus on the synthesis of these perspectives in Neo-Confucian religious thought. I will argue that these forms of non-theistic belief should be considered aspects of Chinese religion, not a separate realm of philosophy. Confucianism, in other words, is a fully religious humanism, not a "secular humanism." The religion of China has traditionally been characterized as having three major strands, the "three religions" (literally "three teachings" or san jiao) of Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism. Buddhism, of course, originated in India in the 5th century BCE and first began to take root in China in the 1st century CE, so in terms of early Chinese thought it is something of a latecomer. Confucianism and Daoism began to take shape between the 5th and 3rd centuries BCE. But these traditions developed in the context of Chinese "popular religion" (also called folk religion or local religion), which may be considered a fourth strand of Chinese religion. And until the early 20th century there was yet a fifth: state religion, or the "state cult," which had close relations very early with both Daoism and Confucianism, but after the 2nd century BCE became associated primarily (but loosely) with Confucianism. -

Issue-05-9.Pdf

THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION of Claims of the Paranormal AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO| • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist York Univ., Toronto Saul Green. PhD, biochemist president of ZOL James E- Oberg, science writer Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, Consultants, New York. NY Irmgard Oepen, professor of medicine (retired). Oregon Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts Marburg, Germany Marcia Angell, M.D., former editor-in-chief, New and Sciences, prof, of philosophy, University Loren Pankratz. psychologist. Oregon Health England Journal of Medicine of Miami Sciences Univ. Robert A. Baker, psychologist. Univ. of Kentucky C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist. Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Stephen Barrett, M.D., psychiatrist, author, Al Hibbs, scientist, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist. MIT consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Massimo Polidoro. science writer, author, execu Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist. Simon Fraser understanding and cognitive science, tive director CICAP, Italy Univ., Vancouver, B.C.. Canada Indiana Univ. Milton Rosenberg, psychologist Univ. of Chicago Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Southern Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics Wallace Sampson. M.D.. clinical professor of medi California and professor of history of science, Harvard Univ. cine. Stanford Univ.. editor, Scientific Review of Susan Blackmore, Visiting Lecturer, Univ. of the Ray Hyman,' psychologist. -

Terminal Lucidity in People with Mental Illness and Other Mental Disability: an Overview and Implications for Possible Explanatory Models

Terminal Lucidity in People with Mental Illness and Other Mental Disability: An Overview and Implications for Possible Explanatory Models Michael Nahm, Ph.D. Freiburg, Germany ABSTRACT: The literature concerned with experiences of the dying contains numerous accounts reporting the sudden return of mental clarity shortly before death. These experiences can be described as Terminal Lucidity (TL). The most peculiar cases concern patients suffering from mental disability including mental illness or dementia. Despite the potential relevance of TL for developing new forms of therapies and for elaborating an improved under- standing of the nature of human consciousness, very little has been published on this subject. In this paper I present a historical overview and selected case reports of TL of mentally ill or otherwise disabled patients, mainly drawing on the literature available in English and in German. Possible explanatory models of TL and their implications are discussed. KEY WORDS: Terminal lucidity; end-of-life experience; mental illness; mental disability; human consciousness. Since Raymond Moody’s (1975) classical publication, near-death experiences (NDEs) have received much attention. Academics and professionals continue to discuss them because of their potentially Michael Nahm, Ph.D., is a biologist. After conducting research in the field of tree physiology for several years, he is presently concerned with developing improved strategies for harvesting woody plants for energetic use. He has a long-standing interest in unsolved problems of evolution and their possible relation to unsolved riddles of the mind and has published a book on these subjects (Evolution und Parapsychologie, 2007). Reprint requests should be addressed to Dr. -

Psi Is Here to Stay Cardeña, Etzel

Psi is here to stay Cardeña, Etzel Published in: Journal of Parapsychology 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Cardeña, E. (2012). Psi is here to stay. Journal of Parapsychology, 76, 17-19. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Volume 76 / Supplement December, 2012 Special Issue Celebrating the 75th Anniversary of the Journal of Parapsychology Where Will Parapsychology Be in the Next 25 Years? Predictions and Prescriptions by 32 Leading Parapsychologists Parapsychology in 25 Years 2 EDITORIAL STAFF JOHN A. PALMER , Editor DAVID ROBERTS , Managing Editor DONALD S. BURDICK , Statistical Editor ROBERT GEBELEIN , Business Manager With the exception of special issues such as this, the Journal of Parapsychology is published twice a year, in Spring and Fall, by the Parapsychology Press, a subsidiary of the Rhine Research Center, 2741 Campus Walk Ave., Building 500, Durham, NC 27705. -

LEASK-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (1.565Mb)

WRAITHS AND WHITE MEN: THE IMPACT OF PRIVILEGE ON PARANORMAL REALITY TELEVISION by ANTARES RUSSELL LEASK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2020 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Timothy Morris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Timothy Richardson Copyright by Antares Russell Leask 2020 Leask iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • I thank my Supervising Committee for being patient on this journey which took much more time than expected. • I thank Dr. Tim Morris, my Supervising Professor, for always answering my emails, no matter how many years apart, with kindness and understanding. I would also like to thank his demon kitten for providing the proper haunted atmosphere at my defense. • I thank Dr. Neill Matheson for the ghostly inspiration of his Gothic Literature class and for helping me return to the program. • I thank Dr. Tim Richardson for using his class to teach us how to write a conference proposal and deliver a conference paper – knowledge I have put to good use! • I thank my high school senior English teacher, Dr. Nancy Myers. It’s probably an urban legend of my own creating that you told us “when you have a Ph.D. in English you can talk to me,” but it has been a lifetime motivating force. • I thank Dr. Susan Hekman, who told me my talent was being able to use pop culture to explain philosophy. It continues to be my superpower. • I thank Rebecca Stone Gordon for the many motivating and inspiring conversations and collaborations. • I thank Tiffany A. -

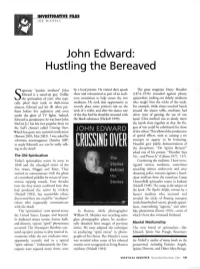

John Edward: Hustling the Bereaved

INVESTIGATIVE FILES JOE NICKELL John Edward: Hustling the Bereaved uperstar "psychic medium" John by a local printer. He visited dieir spook The great magician Harry Houdini Edward is a stand-up guy. Unlike show and volunteered as part of an audi- (1874—1926) crusaded against phony the spiritualists of yore, who typi- ence committee to help secure the two spiritualists, seeking out elderly mediums S mediums. He took that opportunity to who taught him the tricks of die trade. cally plied their trade in dark-room seances, Edward and his ilk often per- secretly place some printer's ink on the For example, while sitters touched hands form before live audiences and even neck of a violin, and after the seance one around die seance table, mediums had under the glare of TV lights. Indeed, of the duo had his shoulder smeared with clever ways of gaining die use of one Edward (a pseudonym: he was born John the black substance (Nickell 1999). hand. (One method was to slowly move MaGee Jr.) has his own popular show on the hands close togedier so diat die fin- die SciFi channel called Crossing Over, gers of one could be substituted for those "which has gone into national syndication JOHN EDWARD of die other.) This allowed die production (Barrett 2001; Mui 2001). I was asked by of special effects, such as causing a tin television newsmagazine Dateline NBC trumpet to appear to be levitating. to study Edward's act: was he really talk- Houdini gave public demonstrations of ing to the dead? HI the deceptions. -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This

Antipoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología ISSN: 1900-5407 Departamento de Antropología, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de los Andes Santo, Diana Espírito; Vergara, Alejandra The Possible and the Impossible: Reflections on Evidence in Chilean Ufology* Antipoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología, no. 41, 2020, October-December, pp. 125-146 Departamento de Antropología, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Universidad de los Andes DOI: https://doi.org/10.7440/antipoda41.2020.06 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=81464973006 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative The Possible and the Impossible: Reflections on Evidence in Chilean Ufology * Diana Espírito Santo** Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile Alejandra Vergara*** Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile https://doi.org/10.7440/antipoda41.2020.06 How to cite this article: Espírito Santo, Diana and Alejandra Vergara. 2020. “The Possible and the Impossible: Reflections on Evidence in Chilean Ufology.” Antípoda. Revista de Antropología y Arqueología 41: 125-146. https://doi.org/10.7440/antipoda41.2020.06 Reception: February 25, 2019; accepted: June 23, 2020; modified: July 31, 2020. Abstract: This article is based on a year of fieldwork with ufologists, contact- 125 ees, abductees, and skeptics in Chile, using methods including ethnography, media and website analysis, and in-depth interviews. Our argument is that the “UFO” serves as, what Galison would call, a theory machine, a multiplic- ity generating not simply heterogeneous interpretive frameworks through which to understand anomalous flying phenomena, in different ideological spheres, but thresholds of evidence as well. -

Jose Alvarez

Jose Alvarez THE KITCHEN In 1988, Jose Alvarez toured Australia channeling the spirit of “Carlos,” a 2,000-year-old shaman who held forth on Atlantis, “corrected” the date of Jesus’s birth, reported on the movements of UFOs, and divined other sundry matters before capacity crowds at the Sydney Opera House. In the voluble tradition of fundamentalist televangelists, healers, and cultish gurus of all stripes, Alvarez charismatically staged the visionary with the help of his mentor James Randi, himself a debunker of paranormal phenomena, who also appears in the recent video Dejeuner Sur Le Dish, 2007, playing chess with Carlos; besides conducting séances, Alvarez peddled vials of tears and potent crystals and proliferated his message via the mass media. But even stranger than Alvarez’s initial hoax was the fact that scores of people were persuaded by it. Indeed, so convincing was his act that its influence survived its debunking. In laying bare the structure of such presentations, Alvarez counterintuitively reaffirmed the possibility of conviction. Even though the aim of his deception was ultimately to enlighten, Carlos’s moral is that people believe against their better judgment in matters of both lesser and greater consequence. Taking this as axiomatic, Alvarez’s first New York solo exhibition, “The Visitors,” furthered his quasi-sociological research into mysticism and magic. Having quit live performance in favor of video and collage, in this show he expanded upon the promise of his earlier work through a range of media. Placed at the gallery’s vestibule, A Separate Reality, 2007, comments on the spectacle of the earlier communions— eventually executed in Europe, Asia, South America, and the United States, as documentary photographs of Alvarez in Italy and China installed alongside the monitor suggested as well—with Alvarez inhabiting the role of the medium and of the whistleblower in turn: Clips corroborating past Carlos embodiments alternate with others culled from CNN, the Today show, and 60 Minutes, where Alvarez affirms his position as a conceptual artist. -

The Way Ahead

THE WAY AHEAD Esalen Survival Seminar Monday Morning Session, May 21, 2007 Adam Crabtree Here are some thoughts about how I presently see our seminar and its directions in the immediate future. We are a group of people from a great diversity of background who are engaged in a study initially centered on survival which has extended into broader fields of psychology and philosophy. I see us as individuals with deep interests in these matters, interests that emerge from both professional and personal experiences. In our discussions there has been a constant interweaving of empirical and theoretical perspectives. How could it be otherwise? Everything we know is based on experience, but we are constantly striving to unify or contextualize or just plain make sense out of that experience. We formulate and reformulate theories in the hope of accomplishing that task. We have recently somewhat shifted the emphasis of our talks toward the theoretical, but that shift is significantly tempered by the fact that if we are going to be effective in our theory-building, we must constantly relate our speculations to experience. In Irreducible Mind we have produced a powerful document which examines the range of psychological and psycho-physical phenomena from the ordinary to the extraordinary, highlighting the neglect of the latter and the need to begin a new era of serious study of the fullness of concrete human experience. Irreducible Mind fittingly concluded with a call for a general theory that would embrace all the “stubborn facts” of human reality. The answer to that call is our projected second book, at this point simply referred to as our “theory-building book.” As I see it, our theory-building book needs to work toward the development of a general theory of human being and experience that is inclusive of all the data and consistent with solidly established but less general theories (such as quantum mechanics). -

Into the Storm Uncovering the Narrative of Qanon

Into the storm Uncovering the narrative of QAnon Ioana Frincu (s1904914) University of Twente BSc. Communication Science Supervisor Menno de Jong “I think that the people who approach the social sciences with a ready-made conspiracy theory thereby deny themselves the possibility of ever understanding what the task of the social sciences is, for they assume that we can explain practically everything in society by asking who wanted it, whereas the real task of the social sciences is to explain those things which nobody wants, such as, for example, a war, or a depression“ (Popper, 2002, p. 168) 1 Abstract The alarming growth of QAnon, a conspiracy theory group, is just the tip of an complex issue which is dividing the world. From conspiracy theories shared on internet to storming Capitol Hill and disrupting the public and political discourse, QAnon quickly become a major threat in the real world. Nevertheless, there is still a limited understanding of its anatomy, characteristic and who are the followers, especially within academia. To address the gap, I will attempt to uncover the narrative of QAnon and its characteristics as the main focus of this research. Conducting a content analysis on 6, 432 posts from Q drops, 8kun, r/QAnon_Casualties and r/Qult_Headquarters implies taking into consideration two opposite perspective: the QAnon insider view and the outsider perspective that takes an anti-QAnon stand. The results are pointing out to an engaging “good vs evil” fight behind the movement as well as cult behavior and a goal to discredit any authority, among others. The conclusion contains several unexplored paths for future research and practical advice to the public and institutions about how to make sense of QAnon.