A Performance Guide to Prokofiev: Romeo and Juliet for Solo Tuba

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Study Guide for Teachers and Students

Melody Mennite in Cinderella. Photo by Amitava Sarkar STUDY GUIDE FOR TEACHERS AND STUDENTS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PRE AND POST-PERFORMANCE ACTIVITIES AND INFORMATION Learning Outcomes & TEKS 3 Attending a ballet performance 5 The story of Cinderella 7 The Artists who Created Cinderella: Choreographer 11 The Artists who Created Cinderella: Composer 12 The Artists who Created Cinderella Designer 13 Behind the Scenes: “The Step Family” 14 TEKS ADDRESSED Cinderella: Around the World 15 Compare & Contrast 18 Houston Ballet: Where in the World? 19 Look Ma, No Words! Storytelling in Dance 20 Storytelling Without Words Activity 21 Why Do They Wear That?: Dancers’ Clothing 22 Ballet Basics: Positions of the Feet 23 Ballet Basics: Arm Positions 24 Houston Ballet: 1955 to Today 25 Appendix A: Mood Cards 26 Appendix B: Create Your Own Story 27 Appendix C: Set Design 29 Appendix D: Costume Design 30 Appendix E: Glossary 31 2 LEARNING OUTCOMES Students who attend the performance and utilize the study guide will be able to: • Students can describe how ballets tell stories without words; • Compare & contrast the differences between various Cinderella stories; • Describe at least one dance from Cinderella in words or pictures; • Demonstrate appropriate audience behavior. TEKS ADDRESSED §117.106. MUSIC, ELEMENTARY (5) Historical and cultural relevance. The student examines music in relation to history and cultures. §114.22. LANGUAGES OTHER THAN ENGLISH LEVELS I AND II (4) Comparisons. The student develops insight into the nature of language and culture by comparing the student’s own language §110.25. ENGLISH LANGUAGE ARTS AND READING, READING (9) The student reads to increase knowledge of own culture, the culture of others, and the common elements of cultures and culture to another. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

The Collected Works of Ambrose Bierce

m ill iiiii;!: t!;:!iiii; PS Al V-ID BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF Henrg W, Sage 1891 B^^WiS _ i.i|j(i5 Cornell University Library PS 1097.A1 1909 V.10 The collected works of Ambrose Blerce. 3 1924 021 998 889 The original of this book is in the Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924021998889 THE COLLECTED WORKS OF AMBROSE BIERCE VOLUME X UIBI f\^^°\\\i COPYHIGHT, 1911, Br THE NEALE PUBLISHING COMPANY CONTENTS PAGE THE OPINIONATOR The Novel 17 On Literary Criticism 25 Stage Illusion 49 The Matter of Manner 57 On Reading New Books 65 Alphab£tes and Border Ruffians .... 69 To Train a Writer 75 As to Cartooning 79 The S. p. W 87 Portraits of Elderly Authors .... 95 Wit and Humor 98 Word Changes and Slang . ... 103 The Ravages of Shakspearitis .... 109 England's Laureate 113 Hall Caine on Hall Gaining . • "7 Visions of the Night . .... 132 THE REVIEWER Edwin Markham's Poems 137 "The Kreutzer Sonata" .... 149 Emma Frances Dawson 166 Marie Bashkirtseff 172 A Poet and His Poem 177 THE CONTROVERSIALIST An Insurrection of the Peasantry . 189 CONTENTS page Montagues and Capulets 209 A Dead Lion . 212 The Short Story 234 Who are Great? 249 Poetry and Verse 256 Thought and Feeling 274 THE' TIMOROUS REPORTER The Passing of Satire 2S1 Some Disadvantages of Genius 285 Our Sacrosanct Orthography . 299 The Author as an Opportunity 306 On Posthumous Renown . -

Romeo and Juliet I

15 Romeo And Juliet I Romeo And Juliet is one of the most famous love stories of all time. It takes Verona place in the city of Verona, Italy. Where is Verona? Verona is a rich and beautiful city in Italy. Map of Italy Copy A Family Feud In Romeo And Juliet, there are two wealthy families, the Capulets and the Montagues. The Capulets and the Montagues are not on good terms. If you are a Capulet, it is your duty to dislike Montagues. If you are a Montague, you will be a disgrace to your family if you are friends with a Capulet. Imagine meeting the person you dislike most! Sampson and Gregory work for the Capulets, while Abraham and Balthasar work for the Montagues. How do you think the men feel when they bump into each other on the streets of Verona? Well, Sampson decides to insult the Montagues. An insult is something rude that people do or say to others. In those days, it was very rude to bite your thumb at someone, and that is whatEvaluation Sampson did when he saw Abraham and Balthasar! 83 Romeo And Juliet I A Quarrel Read the following script aloud. Then act out the story. Characters Sampson Abraham (from the house of Capulet) (from the house of Capulet) Balthasar Gregory (from the house of Montague) (from the house of Montague) Benvolio (a Montague) Tybalt (a Capulet) Other members of the Citizens two families Setting Copy Verona SAMPSON I will bite my thumb at them. That’s a great insult! ABRAHAM (noticing SAMPSON) Do you bite your thumb at us, sir? SAMPSON I do bite my thumb, sir. -

Romeo & Juliet

Romeo and Juliet The Atlanta Shakespeare Company Staff Artistic Director Jeff Watkins Director of Education and Training Laura Cole Development Director Rivka Levin Education Staff Kati Grace Brown, Tony Brown, Andrew Houchins, Adam King, Amanda Lindsey, Samantha Smith Box Office Manager Becky Cormier Finch Art Manager Amee Vyas Marketing Manager Jeanette Meierhofer Company Manager Joe Rossidivito Unless otherwise noted, photos appearing in this study guide are courtesy of Jeff Watkins. Study guide by Samantha Smith The Atlanta Shakespeare Company 499 Peachtree St NE Atlanta GA 30308 404-874-5299 www.shakespearetavern.com Like the Atlanta Shakespeare Company on Facebook and follow ASC on Twitter at @shakespearetav. DIRECTOR'S NOTE ONe of the thiNgs I love most about Shakespeare is that his stories prejudices are too deep aNd too violeNt to be overcome carry differeNt meaNiNgs for me at differeNt poiNts iN my life. by youNg love; iNstead it takes the deaths of two What resoNates for me about the story of Romeo aNd Juliet right iNtelligeNt, kiNd, empathetic youNg people to make the Now is the impact aNd terrible cost of prejudice aNd hatred for the feudiNg Capulets aNd MoNtagues fiNally call each other people iN the play. The Capulets aNd MoNtagues are Not writteN "brother." Right Now, that's the part of this story that's as villaiNs. They are ordiNary people who go about their busiNess moviNg me the most: the warNiNg call to examiNe our aNd care for their owN. But they have beeN raised to hate each owN grudges aNd prejudices aNd thiNk about the other aNd are set iN their ways; they stubborNly adhere to their coNsequeNces of those prejudices for ourselves aNd geNeratioNs-old family feud, refusiNg to let their old grudges go others. -

Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets Of

Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927) By © 2017 Matthew Butterfield DMA, University of Kansas, 2017 M.M., University of Wisconsin-Madison, 2011 B.S., The Pennsylvania State University, 2009 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts. Chair: Dr. Margaret Marco Dr. Colin Roust Dr. Sarah Frisof Dr. Eric Stomberg Dr. Michelle Hayes Date Defended: 2 May 2017 The dissertation committee for Matthew Butterfield certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Léon Goossens and the Oboe Quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927) Chair: Dr. Margaret Marco Date Approved: 10 May 2017 ii Abstract Léon Goossens’s virtuosity, musicality, and developments in playing the oboe expressively earned him a reputation as one of history’s finest oboists. His artistry and tone inspired British composers in the early twentieth century to consider the oboe a viable solo instrument once again. Goossens became a very popular and influential figure among composers, and many works are dedicated to him. His interest in having new music written for oboe and strings led to several prominent pieces, the earliest among them being the oboe quintets of Arnold Bax (1922) and Arthur Bliss (1927). Bax’s music is strongly influenced by German romanticism and the music of Edward Elgar. This led critics to describe his music as old-fashioned and out of touch, as it was not intellectual enough for critics, nor was it aesthetically pleasing to the masses. -

The Musical Partnership of Sergei Prokofiev And

THE MUSICAL PARTNERSHIP OF SERGEI PROKOFIEV AND MSTISLAV ROSTROPOVICH A CREATIVE PROJECT SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC IN PERFORMANCE BY JIHYE KIM DR. PETER OPIE - ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA DECEMBER 2011 Among twentieth-century composers, Sergei Prokofiev is widely considered to be one of the most popular and important figures. He wrote in a variety of genres, including opera, ballet, symphonies, concertos, solo piano, and chamber music. In his cello works, of which three are the most important, his partnership with the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich was crucial. To understand their partnership, it is necessary to know their background information, including biographies, and to understand the political environment in which they lived. Sergei Prokofiev was born in Sontovka, (Ukraine) on April 23, 1891, and grew up in comfortable conditions. His father organized his general education in the natural sciences, and his mother gave him his early education in the arts. When he was four years old, his mother provided his first piano lessons and he began composition study as well. He studied theory, composition, instrumentation, and piano with Reinhold Glière, who was also a composer and pianist. Glière asked Prokofiev to compose short pieces made into the structure of a series.1 According to Glière’s suggestion, Prokofiev wrote a lot of short piano pieces, including five series each of 12 pieces (1902-1906). He also composed a symphony in G major for Glière. When he was twelve years old, he met Glazunov, who was a professor at the St. -

Into the Woods Character Descriptions

Into The Woods Character Descriptions Narrator/Mysterious Man: This role has been cast. Cinderella: Female, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: G3. A young, earnest maiden who is constantly mistreated by her stepmother and stepsisters. Jack: Male, age 20 to 30. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: B2. The feckless giant killer who is ‘almost a man.’ He is adventurous, naive, energetic, and bright-eyed. Jack’s Mother: Female, age 50 to 65. Vocal range top: Gb5. Vocal range bottom: Bb3. Browbeating and weary, Jack’s protective mother who is independent, bold, and strong-willed. The Baker: Male, age 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G4. Vocal range bottom: Ab2. A harried and insecure baker who is simple and loving, yet protective of his family. He wants his wife to be happy and is willing to do anything to ensure her happiness but refuses to let others fight his battles. The Baker’s Wife: Female, age: 35 to 45. Vocal range top: G5. Vocal range bottom: F3. Determined and bright woman who wishes to be a mother. She leads a simple yet satisfying life and is very low-maintenance yet proactive in her endeavors. Cinderella’s Stepmother: Female, age 40 to 50. Vocal range top: F#5. Vocal range bottom: A3. The mean-spirited, demanding stepmother of Cinderella. Florinda And Lucinda: Female, 25 to 35. Vocal range top: Ab5. Vocal range bottom: C4. Cinderella’s stepsisters who are black of heart. They follow in their mother’s footsteps of abusing Cinderella. Little Red Riding Hood: Female, age 18 to 20. -

95.3 Fm 95.3 Fm

October/NovemberMarch/April 2013 2017 VolumeVolume 41, 46, No. No. 3 1 !"#$%&'95.3 FM Brahms: String Sextet No. 2 in G, Op. 36; Marlboro Ensemble Saeverud: Symphony No. 9, Op. 45; Dreier, Royal Philharmonic WHRB Orchestra (Norwegian Composers) Mozart: Clarinet Quintet in A, K. 581; Klöcker, Leopold Quartet 95.3 FM Gombert: Missa Tempore paschali; Brown, Henry’s Eight Nielsen: Serenata in vano for Clarinet,Bassoon,Horn, Cello, and October-November, 2017 Double Bass; Brynildsen, Hannevold, Olsen, Guenther, Eide Pokorny: Concerto for Two Horns, Strings, and Two Flutes in F; Baumann, Kohler, Schröder, Concerto Amsterdam (Acanta) Barrios-Mangoré: Cueca, Aire de Zamba, Aconquija, Maxixa, Sunday, October 1 for Guitar; Williams (Columbia LP) 7:00 am BLUES HANGOVER Liszt: Grande Fantaisie symphonique on Themes from 11:00 am MEMORIAL CHURCH SERVICE Berlioz’s Lélio, for Piano and Orchestra, S. 120; Howard, Preacher: Professor Jonathan L. Walton, Plummer Professor Rickenbacher, Budapest Symphony Orchestra (Hyperion) of Christian Morals and Pusey Minister in The Memorial 6:00 pm MUSIC OF THE SOVIET UNION Church,. Music includes Kodály’s Missa brevis and Mozart’s The Eve of the Revolution. Ave verum corpus, K. 618. Scriabin: Sonata No. 7, Op. 64, “White Mass” and Sonata No. 9, 12:30 pm AS WE KNOW IT Op. 68, “Black Mass”; Hamelin (Hyperion) 1:00 pm CRIMSON SPORTSTALK Glazounov: Piano Concerto No. 2 in B, Op. 100; Ponti, Landau, 2:00 pm SUNDAY SERENADE Westphalian Orchestra of Recklinghausen (Turnabout LP) 6:00 pm HISTORIC PERFORMANCES Rachmaninoff: Vespers, Op. 37; Roudenko, Russian Chamber Prokofiev: Violin Concerto No. 2 in g, Op. -

MUSICAL CENSORSHIP and REPRESSION in the UNION of SOVIET COMPOSERS: KHRENNIKOV PERIOD Zehra Ezgi KARA1, Jülide GÜNDÜZ

SAYI 17 BAHAR 2018 MUSICAL CENSORSHIP AND REPRESSION IN THE UNION OF SOVIET COMPOSERS: KHRENNIKOV PERIOD Zehra Ezgi KARA1, Jülide GÜNDÜZ Abstract In the beginning of 1930s, institutions like Association for Contemporary Music and the Russian Association of Proletarian Musicians were closed down with the aim of gathering every study of music under one center, and under the control of the Communist Party. As a result, all the studies were realized within the two organizations of the Composers’ Union in Moscow and Leningrad in 1932, which later merged to form the Union of Soviet Composers in 1948. In 1948, composer Tikhon Khrennikov (1913-2007) was appointed as the frst president of the Union of Soviet Composers by Andrei Zhdanov and continued this post until the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991. Being one of the most controversial fgures in the history of Soviet music, Khrennikov became the third authority after Stalin and Zhdanov in deciding whether a composer or an artwork should be censored or supported by the state. Khrennikov’s main job was to ensure the application of socialist realism, the only accepted doctrine by the state, on the feld of music, and to eliminate all composers and works that fell out of this context. According to the doctrine of socialist realism, music should formalize the Soviet nationalist values and serve the ideals of the Communist Party. Soviet composers should write works with folk music elements which would easily be appreciated by the public, prefer classical orchestration, and avoid atonality, complex rhythmic and harmonic structures. In this period, composers, performers or works that lacked socialist realist values were regarded as formalist. -

Program Notes by Dr

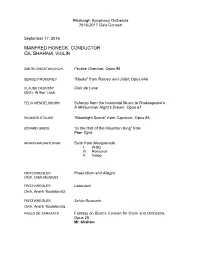

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2016-2017 Gala Concert September 17, 2016 MANFRED HONECK, CONDUCTOR GIL SHAHAM, VIOLIN DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH Festive Overture, Opus 96 SERGEI PROKOFIEV “Masks” from Romeo and Juliet, Opus 64a CLAUDE DEBUSSY Clair de Lune Orch. Arthur Luck FELIX MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from the Incidental Music to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Opus 61 RICHARD STAUSS “Moonlight Scene” from Capriccio, Opus 85 EDVARD GREIG “In the Hall of the Mountain King” from Peer Gynt ARAM KHACHATURIAN Suite from Masquerade I. Waltz IV. Romance V. Galop FRITZ KREISLER Praeludium and Allegro Orch. Clark McAlister FRITZ KREISLER Liebesleid Orch. André Kostelanetz FRITZ KREISLER Schön Rosmarin Orch. André Kostelanetz PABLO DE SARASATE Fantasy on Bizet’s Carmen for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 25 Mr. Shaham Sept. 17, 2016, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH (1906-1975) Festive Overture, Opus 96 (1954) Among the grand symphonies, concertos, operas and chamber works that Dmitri Shostakovich produced are also many occasional pieces: film scores, tone poems, jingoistic anthems, brief instrumental compositions. Though most of these works are unfamiliar in the West, one — the Festive Overture — has been a favorite since it was written in the autumn of 1954. Shostakovich composed it for a concert on November 7, 1954 commemorating the 37th anniversary of the Russian Revolution, but its jubilant nature suggests it may also have been conceived as an outpouring of relief at the death of Joseph Stalin one year earlier. One critic suggested that the Overture was “a gay picture of streets and squares packed with a young and happy throng.” As its title suggests, the Festive Overture is a brilliant affair, full of fanfare and bursting spirits. -

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers Prokofiev Gave up His Popularity and Wrote Music to Please Stalin. He Wrote Music

Teacher Notes on Russian Music and Composers x Prokofiev gave up his popularity and wrote music to please Stalin. He wrote music to please the government. x Stravinsky is known as the great inventor of Russian music. x The 19th century was a time of great musical achievement in Russia. This was the time period in which “The Five” became known. They were: Rimsky-Korsakov (most influential, 1844-1908) Borodin Mussorgsky Cui Balakirev x Tchaikovsky (1840-’93) was not know as one of “The Five”. x Near the end of the Stalinist Period Prokofiev and Shostakovich produced music so peasants could listen to it as they worked. x During the 17th century, Russian music consisted of sacred vocal music or folk type songs. x Peter the Great liked military music (such as the drums). He liked trumpet music, church bells and simple Polish music. He did not like French or Italian music. Nor did Peter the Great like opera. Notes Compiled by Carol Mohrlock 90 Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky (1882-1971) I gor Stravinsky was born on June 17, 1882, in Oranienbaum, near St. Petersburg, Russia, he died on April 6, 1971, in New York City H e was Russian-born composer particularly renowned for such ballet scores as The Firebird (performed 1910), Petrushka (1911), The Rite of Spring (1913), and Orpheus (1947). The Russian period S travinsky's father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was a bass singer of great distinction, who had made a successful operatic career for himself, first at Kiev and later in St. Petersburg. Igor was the third of a family of four boys.