Gaelic Medium Primary Education in Scotland As the Forefront of a Cultural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PURPOSE of REPORT to Consider a Revenue Funding Bid from Fèisean Nan Gàidheal for 2018/19

COMATAIDH BUILEACHAIDH PLANA CÀNAN 19 FEBRUARY 2018 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE 21 FEBRUARY 2018 FÈISEAN NAN GÀIDHEAL REVENUE FUNDING 2018/19 Report by Director of Development PURPOSE OF REPORT To consider a revenue funding bid from Fèisean nan Gàidheal for 2018/19. COMPETENCE 1.1 There are no legal, financial, equalities or other constraints to the recommendations being implemented. Provision exists within the Development Department and Sgiobha na Gaidhlig Revenue Budgets. SUMMARY 2.1 Since 2009 the Comhairle have awarded funding to Fèisean nan Gàidheal on an annual basis to be devolved to six (increasing to seven in 2013) island Fèisean and to support the post of Western Isles Fèis Development Officer. This enables seven week long community- based Gaelic arts tuition festivals to take place between April and August in the Outer Hebrides, plus a varied programme of classes and additional projects throughout the year. 2.2 The Fèis movement has helped ensure that Scottish Gaelic traditions are passed onto new generations of children in the Outer Hebrides, interests in traditional music, song, dance and Gaelic drama are sparked and life-enhancing skills developed. Many Fèis participants have gone on to further study and successful careers in the Creative Industries. The annual Fèis week and year round activities create employment opportunities for traditional artistes based in the Outer Hebrides. 2.3 Fèisean activities enhance the quality of life in remote communities across the islands, helping to make these communities attractive places to bring up a family. The review of the Funding Agreement for 2017-18 has concluded that Fèisean nan Gàidheal has met all requirements, that current arrangements work effectively, delivering a wide ranging and vibrant programme of cultural and creative activity throughout the Outer Hebrides and providing significant economic and social benefits within the local economy. -

Small Languages, Big Interventions: Institutional Support for Gaelic in Scotland”, Luenga & Fablas, 19 (2015), Pp

Luenga & fablas, 19 (2015) I.S.S.N.: 1137-8328 MACLEOD, Marsaili: “Small languages, big interventions: institutional support for Gaelic in Scotland”, Luenga & fablas, 19 (2015), pp. 19-30. Small languages, big interventions: institutional support for Gaelic in Scotland Marsaili MACLEOD (University of Aberdeen & Soillse, the National Research Network for Gaelic Revitalisation) 1. Introduction Let me begin with a brief introduction to Gaelic. Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig), along with Irish and Manx, is a member of the Goidelic branch of Celtic languages. It is well-known to international language scholars as a case of language death due to Nancy Dorian’s research on East Sutherland Gaelic. Her landmark book Language Death describes one community’s dialect in its final phases of obsolescence at the end of the 1970s. The central theme of my paper today is, in happy contrast, ‘language revitalisation’, not ‘language death’. This orientation reflects the serious attempts to revitalise Gaelic over the past three decades through co-ordinated Gaelic planning and policy interventions. Figure 1: Percentage of Population who Speak Gaelic by Parishes in Scotland, 1891-2001 The so-called traditional territory, the ‘Gàidhealtachd’, emerged as a distinct Gaelic speaking region arund the 14th Century in contrast to the Anglo ‘Lowlands’. A pattern of Gaelic language decline over the centuries has meant the near loss of Gaelic from the majority of formerly Gaelic-speaking mainland communities, as these maps illustrate. One consequence is that Gaelic has been perceived as a regional and not 19 Luenga & fablas, 19 (2015) I.S.S.N.: 1137-8328 national language of Scotland. -

Luchd-Teagaisg | Tutors Mairi Innes (Drumaichean | Drums) – Mairi Plays with the Dùn Mòr Ceilidh Band and Comes from the Isle of Benbecula

£1 Diluain 4 gu Dihaoine 8 an t-Iuchar Monday 4 July - Friday 8 July a week-long festival celebrating Tiree’s traditional culture ar ceòl, ar cànan ’s ar dualchas our music, our language and our culture Taic | Contact We want you to have a special week. If you need anything, feel welcome to ask a committee member at the school or An Talla or call Shari MacKinnon on 07810 364 597. Oideachadh | Classes Once again this year we have a great line up, with lots of new tutors! Classes are being held in Tiree High School in Cornaigmore on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday. There will be a temporary halt on Wednesday, for the Muse Cruise! This will see Fèis Thiriodh being transported on a six hour floating session with the tutors on the MV Clansman for a round trip to Barra and back. Come along to sing, play or just listen. What better way to learn the real secrets of traditional culture? Classes this year are: pipes and chanter, Gaelic drama, fiddle, guitar, drums, Gaelic singing, accordion, keyboard, flute and whistle, Gaelic conversation, Highland dancing and film making. Children aged 9 and over and adults are very welcome to come to the main Fèis! Once again Fèis Bheag will run for the full Fèis day - 10.30 am to 3.30 pm – and will be open to all kids aged 5-8, whether they speak Gaelic or not. For under 5s there will be activity sessions on Monday 4th, Tuesday 5th, Thursday 7th and Friday 8th, 10.45 – 11.15, games, songs & rhymes led by Linda MacLeod and Iona Brown. -

Reconstruction of a Gaelic World in the Work of Neil M. Gunn and Hugh Macdiarmid

Paterson, Fiona E. (2020) ‘The Gael Will Come Again’: Reconstruction of a Gaelic world in the work of Neil M. Gunn and Hugh MacDiarmid. MPhil(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/81487/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘The Gael Will Come Again’: Reconstruction of a Gaelic world in the work of Neil M. Gunn and Hugh MacDiarmid Fiona E. Paterson M.A. (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Scottish Literature School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow June 2020 Abstract Neil Gunn and Hugh MacDiarmid are popularly linked with regards to the Scottish Literary Renaissance, the nation’s contribution to international modernism, in which they were integral figures. Beyond that, they are broadly considered to have followed different creative paths, Gunn deemed the ‘Highland novelist’ and MacDiarmid the extremist political poet. This thesis presents the argument that whilst their methods and priorities often differed dramatically, the reconstruction of a Gaelic world - the ‘Gaelic Idea’ - was a focus in which the writers shared a similar degree of commitment and similar priorities. -

Gaelic Nova Scotia an Economic, Cultural, and Social Impact Study

Curatorial Report No. 97 GAELIC NOVA SCOTIA AN ECONOMIC, CULTURAL, AND SOCIAL IMPACT STUDY Michael Kennedy 1 Nova Scotia Museum Halifax, Nova Scotia Canada November 2002 Maps of Nova Scotia GAELIC NOVA SCOTIA AN ECONOMIC, CULTURAL, AND SOCIAL IMPACT STUDY Michael Kennedy Nova Scotia Museum Halifax, Nova Scotia Canada Nova Scotia Museum 1747 Summer Street Halifax, Nova Scotia B3H 3A6 © Crown copyright, Province of Nova Scotia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing from the Nova Scotia Museum, or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Nova Scotia Museum at the above address. Cataloguing in Publication Data ISBN 0-88871-774-1 CONTENTS Introduction 1 Section One: The Marginalization of Gaelic Celtic Roots 10 Gaelic Settlement of Nova Scotia 16 Gaelic Nova Scotia 21 The Status of Gaelic in the 19th Century 27 The Thin Edge of The Wedge: Education in 19th-Century Nova Scotia 39 Gaelic Language and Status: The 20th Century 63 The Multicultural Era: New Initiatives, Old Problems 91 The Current Status of Gaelic in Nova Scotia 112 Section Two: Gaelic Culture in Nova Scotia The Social Environment 115 Cultural Expression 128 Gaelic and the Modern Media 222 Gaelic Organizations 230 Section Three: Culture and Tourism The Community Approach 236 The Institutional Approach 237 Cultural Promotion 244 Section Four: The Gaelic Economy Events 261 Lessons 271 Products 272 Recording 273 Touring 273 Section Five: Looking Ahead Strengths of Gaelic Nova Scotia 275 Weaknesses 280 Opportunities 285 Threats 290 Priorities 295 Bibliography Selected Bibliography 318 INTRODUCTION Scope and Method Scottish Gaels are one of Nova Scotia’s largest ethnic groups, and Gaelic culture contributes tens of millions of dollars per year to the provincial economy. -

EMC Music and Heritage 2. Druckversion.Indd

This publication is a European Year of Cultural Heritage follow-up. The European Music Council is supported by: This publication reflects the views of the EMC only and the European Com- mission cannot be held responsible for any use which may be made of the information contained therein. SNAPSHOTS ON MUSIC AND HERITAGE IN EUROPE Edited by the European Music Council The European Music Council (EMC) is a non-profit organisation dedicated to the development and promotion of all genres and types of music in Europe. It advocates access to music for all and for freedom of musical expression across Europe. As part of the International Music Council (IMC), the EMC strategies and actions are based on the 5 IMC Music Rights. The EMC network comprises music organisations involved in the fields of mu- sic education, creation, performance, participation, production and heritage. As a membership organisation, it provides real value to its members through the analysis of policy developments and the formulation of policy statements, capacity building and knowledge exchange as well as networking opportunities within and beyond the music sector on an international platform. IMPRINT © European Music Council, Bonn, Germany All rights reserved. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and not necessarily of the publisher or editor. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced in any format without permission of the European Music Council. Editor: European Music Council, Haus der Kultur Weberstr. 59a, 53113 Bonn Tel.: +49-228-96699664 -

Language Dynamics in the Marketing of Gaelic Music Alison Lang & Wilson Mcleod

Gaelic culture for sale: language dynamics in the marketing of Gaelic music Alison Lang & Wilson McLeod Scottish Gaelic culture is strongly identified with its musical tradition, and Gaelic song — both recorded and performed live — has become an increasingly popular element of Scotland’s vibrant traditional music scene. At the same time, Gaelic organisations have identified Gaelic music, and Gaelic culture more generally, as a key resource for language development in Scotland. The audience (or, to put it more directly, the market) for Gaelic song thus consists not only of the Gaelic community but many English monoglots as well—a linguistic dynamic that presents significant challenges in terms of how this material is packaged and transmitted. In this paper we look at how Gaelic and English are used in presenting Gaelic music, and Gaelic culture more generally, to this audience (or these audiences). In doing so, we consider what role this cultural dynamic is playing within the conceptualisation and implementation of Gaelic development strategies. The focus here is on recorded rather than live musical performance (although interesting research could be conducted into performers’ practices with regard to language use in the context of live performance), considering the ways in which commercial recordings of Gaelic music are ‘packaged’ in linguistic terms. We began with the observation that there appears to be too much English around Gaelic music — too much English spoken where Gaelic songs are sung and too much English written where Gaelic songs are presented and explained — and that this is problematic from the standpoint of Gaelic language maintenance and development. -

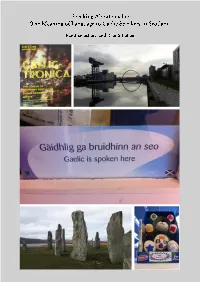

Speaking About Gaelic: the Meaning of Language to Gaelic Speakers in Scotland

Speaking About Gaelic: The Meaning of Language to Gaelic Speakers in Scotland Matthias Schmal and Roos Scholten Speaking About Gaelic: The meaning of language to Gaelic Speakers in Scotland Bachelor thesis 2015-2016 Matthias Schmal 3798526 [email protected] Roos Scholten 4006127 [email protected] June 24, 2016 Coordinator: Jesse Jonkman Wordcount: 20 940 4 Speaking About Gaelic: The meaning of Language to Gaelic speakers in Scotland 5 Matthias Schmal and Roos Scholten Contents Map of Scotland 7 Acknowledgements 9 Introduction 10 1. Theoretical framework 13 Introduction 13 1.1. Identity 13 1.2. Traditions and history in national imagination 15 1.3. Language makes the community 16 1.4. Abstract systems and the risks of a globalizing world 18 2. Gaelic speakers and Scottish nationalism 21 Introduction 21 2.1. Scottish nationalism 21 2.2. Gaelic as an invented tradition 21 2.3. Gaelic Medium Education and the Gaelic revival 22 2.4. Research locations 24 3. Gaelic in the ‘Homeland’ of the language 25 Introduction 25 3.1. An island community 25 3.2. Speaking and imagining Gaelic 27 3.2.1. Country pumpkins and worlds of opportunities 28 3.2.2. Language use as a reflection of its status 29 3.3. Incomers and island traditions 29 3.3.1. The importance of tradition 30 3.3.2. Distinguishing national and local ways of identification 30 3.4. Language planning and the island perspective 32 3.4.1. A focus on education 32 3.4.2. Modernization of the language 33 4. -

The Isle of Skye & Lochalsh

EXPLORE 2020-2021 the isle of skye & lochalsh an t-eilean sgitheanach & loch aillse visitscotland.com Contents 2 Skye & Lochalsh at a glance 4 Amazing activities 6 Great outdoors The Cuillin Hills Hotel is set within fifteen acres of private grounds 8 Touching the past over looking Portree Harbour and the Cuillin Mountain range. 10 Arts, crafts and culture Located on the famous Isle of Skye, you can enjoy one of the finest 12 Natural larder 14 Year of Coasts most spectacular views from any hotel in Scotland. and Waters 2020 16 What’s on 18 Travel tips Welcome to… 20 Practical information 24 Places to visit the isle of 36 Leisure activities skye & lochalsh 41 Shopping Fàilte don at t-eilean 46 Food & drink sgitheanach & loch aillse 55 Tours 59 Transport 61 Events & festivals Are you ready for an island adventure unlike any other? The Isle of Skye and the area of Lochalsh (the part of mainland just to the east of Skye) is 61 Local services a dramatic landscape with miles of beautiful coastline, soaring mountain 62 Accommodation ranges, amazing wildlife and friendly people. Come and be enchanted 68 Regional map by fascinating tales of its turbulent history in the ancient castles, defensive duns and tiny crofthouses, and take in some of the special events happening this year. Cover: The view from Elgol, Inspire your creative spirit on the Skye & Isle of Skye Lochalsh Arts & Crafts Trail (SLACA), cross the beautiful Skye Bridge and don’t miss Above image: Kilt Rock, the chance to sample the best local Isle of Skye produce from land and sea in our many Credits: © VisitScotland. -

Mairi Performance CV March 11

Màiri Christina Macleod BMus (Hons) QTS FRSM Performer/Teacher/Composer Concert Harp, Clàrsach, Electro Harp & Voice Plumptre House, 21 The Liberty, Wells, Somerset, BA5 2SZ. Mob: 0772 512 8807 Phone: 01749 834 328 DOB: 22nd August 1987 E-Mail: [email protected] Web: www.mairimacleod.co.uk EDUCATION & QUALIFICATIONS: 2009 ABRSM - FRSM in Harp Music Performance 2007 - 2009 Manchester Metropolitan University – QTS Secondary Music Teaching 2005 - 2009 Royal Northern College of Music – BMus (Hons) 2.1 2008 ABRSM - registered Music Medals Teacher-Assessor 1999 - 2005 The City of Edinburgh Music School, Broughton High School, Edinburgh. TEACHING EXPERIENCE: Sept ‘11 - Present Wells Cathedral School - Graduate Music Assistant and House Assistant in Senior Girls boarding house. July ‘11 - Present Conductor of the ‘Carloway Gaelic Choir’ from the Isle of Lewis - coaching has to be given via Skype for performances and competitions as the choir is dispersed across the UK but has its base on the island. August ’03 - Present Private teaching - Harp, Voice, Theory, Aural, Composition, Music history & analysis. July ‘02 - ‘11 Fèis Eilean an Fhraoich, Isle of Lewis • Clàrsach teaching at Gaelic summer school • Co-directing the massed instrumental ensemble • Co-organising the Ceilidhs and the music, incorporating the ‘Teen Fèis’ pupils. • Teaching through the medium of Gaelic April ‘10 - July ‘11 St Edmund Arrowsmith Catholic High School - Secondary Music teaching (KS3 & KS4) Sept ‘09 - July ‘10 Cumbria Harp Teaching (1 day/wk) - Queen Elizabeth School, -

BBC Performance Against Public Commitments 2011/12

PERFORMANCE AGAINST PUBLIC COMMITMENTS 2011/12 Contents S1 Ofcom and BBC Trust responsibilities S2 Ofcom Tier 2 quotas S3 Performance against Statements of Programme Policy 2011/12 S20 Access services S21 Window of Creative Competition (WoCC) 1 – OFCOM AND BBC TRUST’S RESPONSIBILITIES Under the terms of the BBC’s Royal Charter, the Agreement, and the Communications Act 2003 (‘the Act’), some areas of the BBC’s activity are regulated by Ofcom, some by the BBC Trust, and some by both together. A Memorandum of Understanding was agreed in March 2007 to clarify the respective roles and responsibilities of the Trust and Ofcom, and the key points are summarised below: Programme standards The BBC Executive is accountable to the BBC Trust for accuracy and impartiality of content; Ofcom sets certain programme standards. Both have duties to consider complaints. Quotas and codes News and current affairs The BBC Trust sets quotas for news and current affairs on BBC One and BBC Two, consulting Ofcom (for agreement in some cases) before imposing these requirements. Original productions The BBC Executive and Ofcom must agree an appropriate proportion of programming to be original productions. Nations and Regions programming The BBC Trust sets quotas for programmes from the Nations and Regions, consulting Ofcom (for agreement in some cases) before imposing these requirements. Programmes made outside London The BBC Executive and Ofcom must agree a suitable proportion of programming to be made in the UK outside the M25 area. Independent production The BBC Trust requires the BBC to follow a code of practice for commissioning independent productions, and reviews delivery against the Window of Creative Competition (WoCC), within which in-house and independent producers can compete for commissions. -

Download (14MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Politics, Pleasures and the Popular Imagination: Aspects of Scottish Political Theatre, 1979-1990. Thomas J. Maguire Thesis sumitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Glasgow University. © Thomas J. Maguire ProQuest Number: 10992141 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10992141 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC.