Language Dynamics in the Marketing of Gaelic Music Alison Lang & Wilson Mcleod

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination

Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900 Silke Stroh northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www .nupress.northwestern .edu Copyright © 2017 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2017. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication data are available from the Library of Congress. Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons At- tribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. In all cases attribution should include the following information: Stroh, Silke. Gaelic Scotland in the Colonial Imagination: Anglophone Writing from 1600 to 1900. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University Press, 2017. For permissions beyond the scope of this license, visit www.nupress.northwestern.edu An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high-quality books open access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the open-access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org Contents Acknowledgments vii Introduction 3 Chapter 1 The Modern Nation- State and Its Others: Civilizing Missions at Home and Abroad, ca. 1600 to 1800 33 Chapter 2 Anglophone Literature of Civilization and the Hybridized Gaelic Subject: Martin Martin’s Travel Writings 77 Chapter 3 The Reemergence of the Primitive Other? Noble Savagery and the Romantic Age 113 Chapter 4 From Flirtations with Romantic Otherness to a More Integrated National Synthesis: “Gentleman Savages” in Walter Scott’s Novel Waverley 141 Chapter 5 Of Celts and Teutons: Racial Biology and Anti- Gaelic Discourse, ca. -

PURPOSE of REPORT to Consider a Revenue Funding Bid from Fèisean Nan Gàidheal for 2018/19

COMATAIDH BUILEACHAIDH PLANA CÀNAN 19 FEBRUARY 2018 SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT COMMITTEE 21 FEBRUARY 2018 FÈISEAN NAN GÀIDHEAL REVENUE FUNDING 2018/19 Report by Director of Development PURPOSE OF REPORT To consider a revenue funding bid from Fèisean nan Gàidheal for 2018/19. COMPETENCE 1.1 There are no legal, financial, equalities or other constraints to the recommendations being implemented. Provision exists within the Development Department and Sgiobha na Gaidhlig Revenue Budgets. SUMMARY 2.1 Since 2009 the Comhairle have awarded funding to Fèisean nan Gàidheal on an annual basis to be devolved to six (increasing to seven in 2013) island Fèisean and to support the post of Western Isles Fèis Development Officer. This enables seven week long community- based Gaelic arts tuition festivals to take place between April and August in the Outer Hebrides, plus a varied programme of classes and additional projects throughout the year. 2.2 The Fèis movement has helped ensure that Scottish Gaelic traditions are passed onto new generations of children in the Outer Hebrides, interests in traditional music, song, dance and Gaelic drama are sparked and life-enhancing skills developed. Many Fèis participants have gone on to further study and successful careers in the Creative Industries. The annual Fèis week and year round activities create employment opportunities for traditional artistes based in the Outer Hebrides. 2.3 Fèisean activities enhance the quality of life in remote communities across the islands, helping to make these communities attractive places to bring up a family. The review of the Funding Agreement for 2017-18 has concluded that Fèisean nan Gàidheal has met all requirements, that current arrangements work effectively, delivering a wide ranging and vibrant programme of cultural and creative activity throughout the Outer Hebrides and providing significant economic and social benefits within the local economy. -

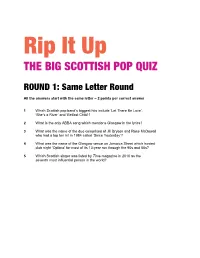

Big Scottish Pop Quiz Questions

Rip It Up THE BIG SCOTTISH POP QUIZ ROUND 1: Same Letter Round All the answers start with the same letter – 2 points per correct answer 1 Which Scottish pop band’s biggest hits include ‘Let There Be Love’, ‘She’s a River’ and ‘Belfast Child’? 2 What is the only ABBA song which mentions Glasgow in the lyrics? 3 What was the name of the duo comprised of Jill Bryson and Rose McDowall who had a top ten hit in 1984 called ‘Since Yesterday’? 4 What was the name of the Glasgow venue on Jamaica Street which hosted club night ‘Optimo’ for most of its 13-year run through the 90s and 00s? 5 Which Scottish singer was listed by Time magazine in 2010 as the seventh most influential person in the world? ROUND 1: ANSWERS 1 Simple Minds 2 Super Trouper (1st line of 1st verse is “I was sick and tired of everything/ When I called you last night from Glasgow”) 3 Strawberry Switchblade 4 Sub Club (address is 22 Jamaica Street. After the fire in 1999, Optimo was temporarily based at Planet Peach and, for a while, Mas) 5 Susan Boyle (She was ranked 14 places above Barack Obama!) ROUND 6: Double or Bust 4 points per correct answer, but if you get one wrong, you get zero points for the round! 1 Which Scottish New Town was the birthplace of Indie band The Jesus and Mary Chain? a) East Kilbride b) Glenrothes c) Livingston 2 When Runrig singer Donnie Munro left the band to stand for Parliament in the late 1990s, what political party did he represent? a) Labour b) Liberal Democrat c) SNP 3 During which month of the year did T in the Park music festival usually take -

The Evolution of Rural Farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: Investments and Inequalities Madalyn Watkins University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Undergraduate Honors Theses 5-2012 The evolution of rural farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: investments and inequalities Madalyn Watkins University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/csesuht Recommended Citation Watkins, Madalyn, "The ve olution of rural farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: investments and inequalities" (2012). Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Undergraduate Honors Theses. 6. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/csesuht/6 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Evolution of Rural Farming in the Scottish Highlands and the Arkansas Delta: Investments and Inequalities An Undergraduate Honors Thesis in the Crop, Soil, and Environmental Science Department Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the University of Arkansas Dale Bumpers College of Agricultural, Food and Life Sciences Honors Program by Madalyn Watkins April 2012 _____________________________________ _____________________________________ ____________________________________ I. Abstract The development and evolution of an agricultural system is influenced by many factors including binding constraints (limiting factors), choice of investments, and historic presence of land and income inequality. This study analyzed the development of two farming systems: mechanized, “economies of scale” farming in the Arkansas Delta and crofting in the Scottish Highlands. The study hypothesized that the current farm size in each region can be partially attributed to the binding constraints of either land or labor. -

Small Languages, Big Interventions: Institutional Support for Gaelic in Scotland”, Luenga & Fablas, 19 (2015), Pp

Luenga & fablas, 19 (2015) I.S.S.N.: 1137-8328 MACLEOD, Marsaili: “Small languages, big interventions: institutional support for Gaelic in Scotland”, Luenga & fablas, 19 (2015), pp. 19-30. Small languages, big interventions: institutional support for Gaelic in Scotland Marsaili MACLEOD (University of Aberdeen & Soillse, the National Research Network for Gaelic Revitalisation) 1. Introduction Let me begin with a brief introduction to Gaelic. Scottish Gaelic (Gàidhlig), along with Irish and Manx, is a member of the Goidelic branch of Celtic languages. It is well-known to international language scholars as a case of language death due to Nancy Dorian’s research on East Sutherland Gaelic. Her landmark book Language Death describes one community’s dialect in its final phases of obsolescence at the end of the 1970s. The central theme of my paper today is, in happy contrast, ‘language revitalisation’, not ‘language death’. This orientation reflects the serious attempts to revitalise Gaelic over the past three decades through co-ordinated Gaelic planning and policy interventions. Figure 1: Percentage of Population who Speak Gaelic by Parishes in Scotland, 1891-2001 The so-called traditional territory, the ‘Gàidhealtachd’, emerged as a distinct Gaelic speaking region arund the 14th Century in contrast to the Anglo ‘Lowlands’. A pattern of Gaelic language decline over the centuries has meant the near loss of Gaelic from the majority of formerly Gaelic-speaking mainland communities, as these maps illustrate. One consequence is that Gaelic has been perceived as a regional and not 19 Luenga & fablas, 19 (2015) I.S.S.N.: 1137-8328 national language of Scotland. -

Luchd-Teagaisg | Tutors Mairi Innes (Drumaichean | Drums) – Mairi Plays with the Dùn Mòr Ceilidh Band and Comes from the Isle of Benbecula

£1 Diluain 4 gu Dihaoine 8 an t-Iuchar Monday 4 July - Friday 8 July a week-long festival celebrating Tiree’s traditional culture ar ceòl, ar cànan ’s ar dualchas our music, our language and our culture Taic | Contact We want you to have a special week. If you need anything, feel welcome to ask a committee member at the school or An Talla or call Shari MacKinnon on 07810 364 597. Oideachadh | Classes Once again this year we have a great line up, with lots of new tutors! Classes are being held in Tiree High School in Cornaigmore on Monday, Tuesday, Thursday and Friday. There will be a temporary halt on Wednesday, for the Muse Cruise! This will see Fèis Thiriodh being transported on a six hour floating session with the tutors on the MV Clansman for a round trip to Barra and back. Come along to sing, play or just listen. What better way to learn the real secrets of traditional culture? Classes this year are: pipes and chanter, Gaelic drama, fiddle, guitar, drums, Gaelic singing, accordion, keyboard, flute and whistle, Gaelic conversation, Highland dancing and film making. Children aged 9 and over and adults are very welcome to come to the main Fèis! Once again Fèis Bheag will run for the full Fèis day - 10.30 am to 3.30 pm – and will be open to all kids aged 5-8, whether they speak Gaelic or not. For under 5s there will be activity sessions on Monday 4th, Tuesday 5th, Thursday 7th and Friday 8th, 10.45 – 11.15, games, songs & rhymes led by Linda MacLeod and Iona Brown. -

Area Irish Music Events

MOHAWK VALLEY IRISH CULTURAL Volume 14, Issue 2 EVENTS NEWSLETTER Feb 2017 2017 GAIF Lineup: Old Friends, New Voices The official lineup for the 2017 Great American Irish Festival was announced at the Halfway to GAIF Hooley held January 29th at Hart’s Hill Inn in Whitesboro, with a broad array of veteran GAIF performers and an equal number of acts making their first appearance at the festival, and styles ranging from the delicate to the raucous. Headlining this year’s festival will be two of the Celtic music world’s most sought-after acts: the “Jimi Hendrix of the Violin,” Eileen Ivers, and Toronto-based Celtic roots rockers, Enter the Haggis. Fiery fiddler Eileen Ivers has established herself as the pre-eminent exponent of the Irish fiddle in the world today. Grammy awarded, Emmy nominated, London Symphony Orchestra, Boston Pops, guest starred with over 40 orchestras, original Musical Star of Riverdance, Nine Time All-Ireland Fiddle Champion, Sting, Hall and Oates, The Chieftains, ‘Fiddlers 3’ with Nadja Salerno-Sonnenberg and Regina Carter, Patti Smith, Al Di Meola, Steve Gadd, founding member of Cherish the Ladies, movie soundtracks including Gangs of New York, performed for Presidents and Royalty worldwide…this is a short list of accomplishments, headliners, tours, and affiliations. Making a welcome return to the stage she last commanded in 2015, Eileen Ivers will have her adoring fans on their feet from the first note. Back again at their home away from home for the 11th time, Enter the Haggis is poised to rip it up under the big tent with all the familiar catchy songs that have made fans of Central New Yorkers and Haggisheads alike for over 15 years. -

Annual Report 2010

Annual Report 2010 Table of Contents 1 Chair’s Foreword 2 2 Fèis Facts 4 3 Key Services and Activities 5 4 Board of Directors 14 5 Staffing Report 15 6 Fèis Membership and Activities 17 7 Financial Statement 2009-10 28 Fèisean nan Gàidheal is a company limited by guarantee, registration number SC130071, registered with OSCR as a Scottish Charity, number SC002040, and gratefully acknowledges the support of its main funders Scottish Arts Council | The Highland Council | Bòrd na Gàidhlig | Highlands & Islands Enterprise Comhairle nan Eilean Siar | Argyll & Bute Council 1 Chair’s Foreword I am delighted to commend to you this year’s Annual Report From Fèisean nan Gàidheal. 2009-10 has been a challenging, and busy, year For the organisation with many highlights, notably the success oF the Fèisean themselves. In difficult economic times, Fèisean nan Gàidheal’s focus will remain on ensuring that support for the Fèisean remains at the heart of this organisation’s efforts. Gaelic drama also continued to flourish with drama Fèisean in schools, Meanbh-Chuileag’s perFormance tour of Gaelic schools and a successFul Gaelic Drama Summer School. In addition work was begun on radio drama in the Iomairtean Gàidhlig areas, continuing to make a valuable contribution to increasing the use oF Gaelic among young people. Fèisean nan Gàidheal continued to develop its use oF Gaelic language with Gaelic training to stafF, volunteers and tutors. Our service provides support to Fèisean to ensure that they produce printed and web materials bilingually, and seeks to help Fèisean ensure a greater Gaelic content in their activities. -

Folk & Roots Festival 2

Inverclyde’s Scottish Folk & Roots Festival 2014 5th October – 15th November Beacon Arts Centre, Greenock TICKETS: 01475 723723 www.beaconartscentre.co.uk FSundayAR 5thFAR October FROM YPRES FAR, FAR FROMSiobhan MillerYPRES N.B.7.30pm Because of the content of the material and the narrative, we would The music, songs and poetry of World War One from a Scottish perspective Sunday 5th October 3pm Welcome back... askMain that Theatre there is no applause until each half is finished. However, it is not to Inverclyde’s Scottish Folk & Roots a production of unremitting gloom, so if you would like to sing some of The Session Festival, brought to you courtesy of Far, Far From Ypres the choruses, please do so. Here’s some help: 1914 2014 Riverside Inverclyde. from “any village in Scotland”, telling of A free (ticketed) event at The Beacon Concessionary tickets of £10 available to his recruitment, training, journey to the Keep the Home-fires burning, When this bloody war is over Beacon Theatre, Greenock Last year’s festival saw audience ages all, subject to availability, until 4th Somme, and return to Scotland. Images This acoustic event is open to new-to- While your hearts are yearning, No more soldiering for me ranging from 8 to mid 80’s. Once again October, thereafter tickets priced at £15. from WW1 are projected onto a screen, Though your lads are far away When I get my civvy clothes on the-festival acts, subject to programme there’s something in the festival for deepening the audience’s understanding of everybody, hopefully offering community They dream of Home; Oh how happy I will be capacity, who register by Monday Ypres – a name forever embedded in the unfolding story. -

Minutes of Proceedings

House of Commons Scottish Affairs Committee Minutes of Proceedings Session 2008–09 The Scottish Affairs Committee The Scottish Affairs Committee is appointed by the House of Commons to examine the expenditure, administration, and policy of the Scotland Office (including (i) relations with the Scottish Parliament and (ii) administration and expenditure of the office of the Advocate General for Scotland but excluding individual cases and advice given within government by the Advocate General). Membership during Session 2008–09 Mr Mohammad Sarwar MP, (Lab, Glasgow Central) (Chairman) Mr Alistair Carmichael, (Lib Dem, Orkney and Shetland) Ms Katy Clark MP, (Lab, North Ayrshire & Arran) Mr Ian Davidson MP, (Lab, Glasgow South West) Mr Jim Devine MP, (Lab, Livingston) Mr Jim McGovern MP, (Lab, Dundee West) David Mundell MP, (Con, Dumfriesshire, Clydesdale and Tweeddale) Lindsay Roy MP, (Labour, Glenrothes) Mr Charles Walker MP, (Con, Broxbourne) Mr Ben Wallace MP, (Con, Lancaster and Wyre) Pete Wishart MP, (SNP, Perth and North Perthshire) Powers The committee is one of the departmental select committees, the powers of which are set out in House of Commons Standing Orders, principally in SO No. 152. These are available on the Internet via www.parliament.uk. Publications The Reports and evidence of the Committee are published by The Stationery Office by Order of the House. All publications of the Committee (including press notices) are on the Internet at www.parliament.uk/parliamentary_committees/scottish_affairs_committee.cfm. Committee staff The staff of the Committee during Session 2008–09 were Charlotte Littleboy (Clerk), Nerys Welfoot (Clerk), Georgina Holmes-Skelton (Second Clerk), Duma Langton (Senior Committee Assistant), James Bowman (Committee Assistant), Becky Crew (Committee Assistant), Karen Watling (Committee Assistant) and Tes Stranger (Committee Support Assistant). -

Reconstruction of a Gaelic World in the Work of Neil M. Gunn and Hugh Macdiarmid

Paterson, Fiona E. (2020) ‘The Gael Will Come Again’: Reconstruction of a Gaelic world in the work of Neil M. Gunn and Hugh MacDiarmid. MPhil(R) thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/81487/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] ‘The Gael Will Come Again’: Reconstruction of a Gaelic world in the work of Neil M. Gunn and Hugh MacDiarmid Fiona E. Paterson M.A. (Hons) Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Scottish Literature School of Critical Studies College of Arts University of Glasgow June 2020 Abstract Neil Gunn and Hugh MacDiarmid are popularly linked with regards to the Scottish Literary Renaissance, the nation’s contribution to international modernism, in which they were integral figures. Beyond that, they are broadly considered to have followed different creative paths, Gunn deemed the ‘Highland novelist’ and MacDiarmid the extremist political poet. This thesis presents the argument that whilst their methods and priorities often differed dramatically, the reconstruction of a Gaelic world - the ‘Gaelic Idea’ - was a focus in which the writers shared a similar degree of commitment and similar priorities. -

Volume 2, Issue 1, Bealtaine 2003

TRISKELE A newsletter of UWM’s Center for Celtic Studies Volume 2, Issue 1 Bealtaine, 2003 Fáilte! Croeso! Mannbet! Kroesan! Welcome! Tá an teanga beo i Milwaukee! The language lives in Milwaukee! UWM has the distinction of being one of a small handful of colleges in North America offering a full program on the Irish language (Gaelic). The tradition began some thirty years ago with the innovative work of the late Professor Janet Dunleavy and her husband Gareth. Today we offer four semesters in conversational Gaelic along with complementary courses in literature and culture and a very popular Study Abroad program in the Donegal Gaeltacht. The study and appreciation of this richest and oldest of European vernacular languages has become one of the strengths and cornerstones of our Celtic Studies program. The Milwaukee community also has a long history of activism in support of Irish language preservation. Jeremiah Curtin, noted linguist and diplomat and the first Milwaukeean to attend Harvard, made it his business to learn Irish among the Irish Gaelic community of Boston. As an ethnographer working for the Smithsonian Institute, he was one of the first collectors of Irish folklore to use the spoken tongue of the people rather than the Hiberno-English used by the likes of William Butler Yeats and Lady Gregory. Jeremiah Quinn, who left Ireland as a young man, capped a lifelong local commitment to Irish language and culture when in 1906, at the Pabst Theatre, he introduced Dr. Douglas Hyde to a capacity crowd, including the Governor, Archbishop, and other dignitaries. Hyde, one of the founders of the Gaelic League that was organized to halt the decline of the language, went on to become the first president of Ireland in 1937.