Joseph Sidebotham: Vicissitudes of a Victorian Collector

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of Polling Districts, Polling Places and Polling Stations Stage

REVIEW OF POLLING DISTRICTS, POLLING PLACES AND POLLING STATIONS STAGE TWO CONSULATION RETURNING OFFICERS PROPOSALS Cheadle & Gatley (A) Existing arrangements Polling Electors Polling Place Disabled District access AA 2379 Trinity Methodist /United Reformed Church Yes Massie Street, Cheadle, Cheshire AB 1673 Mobile Polling Station Yes Oakwood Avenue AC 1243 Gatley Primary School, Hawthorn Road, Gatley Yes Cheadle AD 2014 The Kingsway School (Upper) Foxland Road, Yes Cheadle, AE 2503 Kingsway School (Lower) High Grove Road, Yes Cheadle AF 1596 The Bowling Pavilion, Gatley Recreation Ground, Yes Northenden Road. Returning officer’s proposal: No change Cheadle Hulme South (B) Existing arrangements Polling Electors Polling Place Disabled District access BA 1420 Bradshaw Hall Primary School, Vernon Close, Yes Cheadle Hulme BB 1678 United Reformed Church, Swann Lane, Cheadle Yes Hulme BC 2381 Bradshaw Hall Primary School, Vernon Close, Yes Cheadle Hulme BD 1480 Thorn Grove Primary School, Woodstock Avenue, Yes Cheadle Hulme BE 1480 St James RC High School Yes St James’ Way Cheadle Hulme BF 1978 The Methodist Church Schoolroom, Yes Station Road, Cheadle Hulme Returning officer’s proposal: No change D:\moderngov\data\published\Intranet\C00000117\M00000288\AI00002471\$jywnn5ae.doc Cheadle Hulme North (C) Existing arrangements Polling Electors Polling Place Disabled District access CA 1742 Queens Road Primary School, Buckingham Road, Yes Cheadle Hulme CB 1564 St. Cuthbert’s Church Yes Stockport Road CC 1556 All Hallows Church Yes 222 Councillor -

Strines- New Mills

More Trips Out from Eccles Station J.E.Rayner 2010 Eighty two MARPLE –STRINES- NEW MILLS. This is an attractive stroll along the Goyt Valley. (For a very easy short walk go as far as Strines Station - trains back to Manchester every two hours so time your walk right). After Strines there is a relentless ascent to Brookbottom (the pub might be open!) followed by wide open views on the quiet lane to New Mills. Take the train to Manchester Victoria and from there a tram to Manchester Piccadilly Station. From here catch a train to Marple (NOT Rose Hill). Option: - turn right as you get off the tram and on Fairfield Street use the lift on the left to the link bridge lounge. STAGE I Alight at Marple Station. Go down the short approach road and turn left to Marple Bridge. Marple Bridge is an attractive stone village. The Midland is a free house selling cask marque real ales, tea, coffee, snacks and full meals. Cross the bridge over the River Goyt and turn right past the shops (The Royal Scot sells Robinson’s real ales). Fork right onto Lower Lea Road, and follow this. At the top of the gentle rise you see the hills ahead. Descend to a T with Lakes Road. Turn left along this. Follow it to the right in front of Bottoms Hall (Charmingly named, impressively sited - Georgian?). Next on the left are some lakes. Called Roman Lakes they are used for boating and fishing –take a look. Pass under the railway viaduct. On the right is a weir. -

Introduction the Whitworth Has Been Making Art Useful Since 1889

Introduction The Whitworth has been making art useful since 1889. The gallery was originally founded with the wealth of Stockport-born engineer Sir Joseph Whitworth (1803-87). He transformed engineering through the introduction of a standardised system of measurement for machine parts. Whitworth left no formal instructions about how the bulk of his fortune (equivalent to more than £130 million today) should be used after his death. This decision was left to his widow Lady Mary Louisa and his good friends and fellow philanthropists Robert Darbishire and Richard Copley Christie. For the very first time examples of Joseph Whitworth’s world-changing mechanical innovations are on display amongst highlights from the gallery’s diverse collections of textiles, fine art and wallpaper. Whitworth’s commitment to standardisation is used throughout the exhibition as a counterpoint to significant moments of deviation within the gallery’s collection and history. This exhibition explores the establishment of the Whitworth. The founding intention to create a forward-thinking art and design collection is interrogated and its difficult histories exposed. Gender, labour, race and class inequalities are just some of the issues being confronted. This has informed our conversations about the history of the gallery and its collections and we continue to actively engage in this work. Art and Industry William Morris described the exhibits inside the Great Exhibition of 1851 as ‘wonderfully ugly’. For Morris and the art critic John Ruskin, this celebration of global arts highlighted how mass production had led to a separation between English workers and making. Both men were prominent in the Arts and Crafts movement, which aimed to promote hand-making over mass production and advocate the decorative arts. -

Winter Service Operational Plan

Stockport Council Winter Service Operational Plan 1 Contents Page Introduction 3 Gritting Priorities 3 Decision Matrix Guide 3 Treatment Matrix Guide 4 Grit Bins 5 Useful Contacts 5 Section1 – Carriageway 6 Routes Section 2 – Footway /off 26 road Cycle Routes Section 3 – Additional Grit 29 Locations Section 4 – Grit Bins 30 2 1. Introduction 1.1. This plan is to be used in conjunction with the most recent Winter Services Policy and the latest version of the Functional Network Hierarchy. 1.2. Within this plan are the current criteria for decision making and the current Carriageway Gritting Routes, Footway/Cycle Gritting Routes, Grit Box and additional Grit Locations. 2. Gritting Priorities 2.1. The criteria for gritting priorities are: 2.2. Routes 1 to 5 including ‘A’ roads, major bus routes and other key transport routes. 2.3. Routes 6 to 10 including secondary bus routes, routes to schools and district feeder roads that carry higher levels of traffic including sites with special circumstances e.g. severe gradients. 2.4. Designated East, West and North Area routes, trailer mounted and supervisor schedules include all other district bus routes and other district roads with steep gradients. 2.5. Current Spread rates and treatments to be used are: 3. Decision Matrix Guide Timing of treatment Treatment Type Freezing rain Salt Spreading Minor Ice Salt Spreading Salt During Snow Spreading/Ploughing Salt After Snow (Slush) Spreading/Ploughing Salt Spreading/Ploughing/ salt and abrasives After Snow (Compact spreading/Abrasives Snow/Ice) spreading NWSRG Practical Guide for Winter Service Treatments for Snow and Ice 3 4. -

Climatic Condition in Mandi Distric

Research Paper Volume : 4 | Issue : 1 | January 2015 • ISSN No 2277 - 8179 Taxonomic Studies on Light Trap Collected Biotechnology Species of Abraxas Leach Under Agro- KEYWORDS : Taxonomic, Genitalia, Wing, Adeagus Climatic Condition in Mandi District of Himachal Pradesh Forest Protection Division, Himalayan Forest Research Institute, Conifer Campus VIKRANT THAKUR Panthaghati, Shimla Himachal Pradesh 171009 MANOJ KUMAR Faculty of Biotechnology, Shoolini university, Solan HP-172230 ABSTRACT The light trap collection by using mercury lamp indicated that Abraxas Leach under agro-climatic condition of Mandi district of Himachal Pradesh is comprises of three species viz. Abraxas picaria Moore, Abraxas leucostola Hampson and Abraxas sylvata Scopoli. These species obatain their peak in July- August . Abraxas leucostola Hampson was found most abundant followed by Abraxas picaria Moore and Abraxas sylvata Scopoli on the basis of daily catches. The taxonomic study on these spe- cies carried out and described in detail. A key to the species of Abraxas Leach has also been provided for their easy identification. Introduction: DEX (Beccaloni et.al. 2003). The hierarchy of different moth is This moth is mostly white with brownish patches across all of given by Van Nieukerken et al. (2011) the wings. There are small areas of pale gray on the forewings and hind wings. They resemble bird droppings while resting on Result: the upper surface of leaves. The adults fly from late May to early Abraxas picaria Moore August. They are attracted to light. The wingspan is 38 mm. to picariaMoore, 1868, Proc. zool. Soc. Lond. 1893(2): 393 (Abraxas). 48 mm. The moth is nocturnal and is easy to find during the day. -

Carmarthenshire Moth & Butterfly Group

CARMARTHENSHIRE MOTH & BUTTERFLY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSUE No.2 JUNE 2006 Editor: Jon Baker (County Moth Recorder for VC44 Carms) INTRODUCTION Welcome to the 2 nd newsletter of the VC44 Moth & Butterfly Group. I received a positive reaction to the 1 st one, so I have decided to continue this experiment, and expand on it. In this edition I have included a couple of articles, as well as looking at some of the recent records in more detail. June has been a notably hot month. Sitting here in sweltering heat at the start of July, I look back on what has been a cracking month for mothing. A good range of our native species has been recorded so far this year, but it has also been an exceptionally good month for migration. Although the south coast of England has fared much better than us, a few things have made it here. A summary of migrant moths can be found below. I’ve decided not to continue including full lists of micro moths recorded, as this is really not of widespread interest, and time and space can be better used elsewhere. If anyone does wish to discuss micros with me, feel free to ask anything. Similarly, as I do not actually receive records of Butterflies, I cannot really do a formal write up of those in these bulletins – although I will continue to mention any personal highlights of those of others that I am aware of. At the end of this edition are a couple of informal articles. One looking at the status of Mouse Moth in the county, the other an identification workshop on the tricky group of “white waves”. -

(Tfgm) Complaints Handling Procedure for Horwich Parkway Station

Marcus Clements Head of Consumer Policy E-mail: [email protected] 22 December 2020 Bob Morris Chief Operating Officer TfGM By Email Dear Bob, Approval of Transport for Greater Manchester’s Complaints Handling Procedure for Horwich Parkway station (Condition 6 of the Station Licence) Thank you for submitting Transport for Greater Manchester (TfGM)’s draft Complaints Handling Procedure (CHP) for Horwich Parkway station for approval. I confirm that we have reviewed your CHP against the 2015 “Guidance on complaints handling procedures for licence holders” (the guidance), and can confirm that your revised CHP meets the requirements of Condition 6 of your station licence. We also sought views on your draft CHP from Transport Focus. We welcome your commitment to respond to 90% of complaints within 5 working days of acknowledgement, which we believe is likely to be positive for passengers. A copy of TfGM’s revised CHP is attached to this letter, and will be published on our website along with a copy of this letter. Yours sincerely, Marcus Clements Customer service policy How we handle complaints about our services at Horwich Parkway station 1 Contents Customer complaints handling procedure Customer complaints handling procedure ��������������������������������������������������� 3 Welcome to Transport for Greater We also consult with Transport Focus and Introduction ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 3 Manchester. Our complaints the Office of Rail and Road (ORR) on an annual basis -

Figure 1. Sharpshooter Weapons in the American Civil War (Photo Ex

ASAC_Vol107_02-Carlson_130003.qxd 8/23/13 7:58 PM Page 2 Figure 1. Sharpshooter Weapons in the American Civil War (photo ex. author's collection). 107/2 Reprinted from the American Society of Arms Collectors Bulletin 107:2-28 Additional articles available at http://americansocietyofarmscollectors.org/resources/articles/ ASAC_Vol107_02-Carlson_130003.qxd 8/23/13 7:58 PM Page 3 Sharpshooter Weapons in the American Civil War By Bob Carlson There is a proud tradition of sharpshooting in the mili- tary history of our nation (Figure 1). From the defeat of General Edward Braddock and the use of flank companies of riflemen in the French and Indian War, to the use of long rifles against Ferguson and the death of General Simon Fraser in the Revolutionary War at Saratoga, to the War of 1812 when British General Robert Ross was shot on the way to take Baltimore in 1814 and when long rifles were instru- mental at New Orleans in January 1815, up to the modern wars with the use of such arms as the Accuracy International AX338 sniper rifle, sharpshooters have been crucial in the outcome of battles and campaigns. I wish to dedicate this discussion to a true American patriot, Chris Kyle, a much decorated Navy Seal sniper whom we lost in February of this year, having earned two silver and four bronze stars in four tours of service to his country. He stated that he killed the enemy to save the lives of his comrades and his only regret was those that he could not save. He also aided his fellow attackers at bay; harassing target officers and artillerymen disabled veterans for whom he worked tirelessly with his from a long-range; instilling psychological fear and feelings Heroes Project after returning home. -

Scottish Macro-Moth List, 2015

Notes on the Scottish Macro-moth List, 2015 This list aims to include every species of macro-moth reliably recorded in Scotland, with an assessment of its Scottish status, as guidance for observers contributing to the National Moth Recording Scheme (NMRS). It updates and amends the previous lists of 2009, 2011, 2012 & 2014. The requirement for inclusion on this checklist is a minimum of one record that is beyond reasonable doubt. Plausible but unproven species are relegated to an appendix, awaiting confirmation or further records. Unlikely species and known errors are omitted altogether, even if published records exist. Note that inclusion in the Scottish Invertebrate Records Index (SIRI) does not imply credibility. At one time or another, virtually every macro-moth on the British list has been reported from Scotland. Many of these claims are almost certainly misidentifications or other errors, including name confusion. However, because the County Moth Recorder (CMR) has the final say, dubious Scottish records for some unlikely species appear in the NMRS dataset. A modern complication involves the unwitting transportation of moths inside the traps of visiting lepidopterists. Then on the first night of their stay they record a species never seen before or afterwards by the local observers. Various such instances are known or suspected, including three for my own vice-county of Banffshire. Surprising species found in visitors’ traps the first time they are used here should always be regarded with caution. Clerical slips – the wrong scientific name scribbled in a notebook – have long caused confusion. An even greater modern problem involves errors when computerising the data. -

Industrial Biography

Industrial Biography Samuel Smiles Industrial Biography Table of Contents Industrial Biography.................................................................................................................................................1 Samuel Smiles................................................................................................................................................1 PREFACE......................................................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER I. IRON AND CIVILIZATION..................................................................................................2 CHAPTER II. EARLY ENGLISH IRON MANUFACTURE....................................................................16 CHAPTER III. IRON−SMELTING BY PIT−COAL−−DUD DUDLEY...................................................24 CHAPTER IV. ANDREW YARRANTON.................................................................................................33 CHAPTER V. COALBROOKDALE IRON WORKS−−THE DARBYS AND REYNOLDSES..............42 CHAPTER VI. INVENTION OF CAST STEEL−−BENJAMIN HUNTSMAN........................................53 CHAPTER VII. THE INVENTIONS OF HENRY CORT.........................................................................60 CHAPTER VIII. THE SCOTCH IRON MANUFACTURE − Dr. ROEBUCK DAVID MUSHET..........69 CHAPTER IX. INVENTION OF THE HOT BLAST−−JAMES BEAUMONT NEILSON......................76 CHAPTER X. MECHANICAL INVENTIONS AND INVENTORS........................................................82 -

GMPR11 Ashburys

Foreword • Contents Some of this country’s most significant nineteenth • and early twentieth century industrial enterprises Introduction .......................................................2 have disappeared leaving surprisingly little The Historic Setting ...........................................6 surviving evidence. This booklet highlights the 19th Century Industrialisation ..........................8 work undertaken as part of recent archaeological investigations looking at two adjoining areas of John Ashbury: The Early Years ...................... 10 the former Ashbury’s Carriage and Iron Works, Ashbury’s In Openshaw 1847-1928 ................. 12 Openshaw, Manchester. Established in 1847, Excavation Of The Foundry ............................22 Ashbury’s grew to be a major supplier both to Products Of The Ashbury Works .....................36 domestic and global markets of iron, steel, rolling stock and railway components. Apart from the Working At The Plant ......................................42 Ashbury’s railway station little or no visible Further Investigation ......................................44 surface evidence survives today of where the Glossary ...........................................................47 works once stood. The company’s archives also Further Reading ..............................................48 appear not to have survived. Acknowledgements ..........................................49 The fragmentary cartographic, documentary and photographic evidence for the history and development of Ashbury’s -

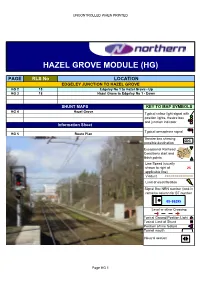

Hazel Grove Module (Hg)

UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED HAZEL GROVE MODULE (HG) PAGE RLS No LOCATION EDGELEY JUNCTION TO HAZEL GROVE HG 2 18 Edgeley No 1 to Hazel Grove - Up HG 3 18 Hazel Grove to Edgeley No 1 - Down SHUNT MAPS KEY TO MAP SYMBOLS HG 4 Hazel Grove Typical colour light signal with position lights, theatre box and junction indicator Information Sheet Typical semaphore signal HG 5 Route Plan Theatre box showing SDG possible destination Exceptional Railhead Conditions start and finish points Line Speed (usually shown to right of 25 applicable line) Viaduct Limit of electrification Signal Box NRN number (look in remarks column for BT number 05-88295 Level or other Crossing Typical Ground Position Light Typical Limit of Shunt Position of line feature Tunnel mouth Neutral section Page HG 1 UNCONTROLLED WHEN PRINTED RLS No 18 Depot - Manchester Piccadilly Drawn by DC 04/06 Checked by SL 24/03/08 Issue 1 02/10 Edgeley Jnc to Hazel Grove - Up Direction. Note:- Differential speed limits may apply to See RLS No 19 this map but only the line speed for class 1, 2 See RLS No 13 and 5 trains and applicable "SP" classes are shown for clarity 40 Hazel Grove East Junction 2.30 40 Limit of electrification HG18 HG20 Hazel Grove Station 2.21 169m DN HOPE VALLEY UP HOPE VALLEY UP HOPE Hazel Grove Signal Box 0161 228 8295 2.21 1 2 169m 05-88295 MR 25 Hazel Grove West Junction 2.10 25 HG14 HG12 HG16 DM DM HG10 UP HOPE VALLEY UP HOPE Exceptional rail head conditions 1.45 HG8 Woodsmoor Station 1.25Short platform! 90m Edgeley No S.B.