AVIATION by Robert W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cardiff Airport and Gateway Development Zone SPG 2019

Vale of Glamorgan Local Development Plan 2011- 2026 Cardiff Airport and Gateway Development Zone Supplementary Planning Guidance Local Cynllun Development Datblygu December 2019 Plan Lleol Vale of Glamorgan Local Development Plan 2011-2026 Cardiff Airport & Gateway Development Zone Supplementary Planning Guidance December 2019 This document is available in other formats upon request e.g. larger font. Please see contact details in Section 9. CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... 1 2. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 3. Purpose of the Supplementary Planning Guidance .................................................................... 3 4. Status of the Guidance .............................................................................................................. 3 5. Legislative and Planning Policy Context .................................................................................... 4 5.1. National Legislation ............................................................................................................. 4 5.2. National Policy Context ....................................................................................................... 4 5.3. Local Policy Context ............................................................................................................ 5 5.4. Supplementary Planning -

Local Authority & Airport List.Xlsx

Airport Consultative SASIG Authority Airport(s) of Interest Airport Link Airport Owner(s) and Shareholders Airport Operator C.E.O or M.D. Committee - YES/NO Majority owner: Regional & City Airports, part of Broadland District Council Norwich International Airport https://www.norwichairport.co.uk/ Norwich Airport Ltd Richard Pace, M.D. Yes the Rigby Group (80.1%). Norwich City Cncl and Norfolk Cty Cncl each own a minority interest. London Luton Airport Buckinghamshire County Council London Luton Airport http://www.london-luton.co.uk/ Luton Borough Council (100%). Operations Ltd. (Abertis Nick Barton, C.E.O. Yes 90% Aena 10%) Heathrow Airport Holdings Ltd (formerly BAA):- Ferrovial-25%; Qatar Holding-20%; Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec-12.62%; Govt. of John Holland-Kaye, Heathrow Airport http://www.heathrow.com/ Singapore Investment Corporation-11.2%; Heathrow Airport Ltd Yes C.E.O. Alinda Capital Partners-11.18%; China Investment Corporation-10%; China Investment Corporation-10% Manchester Airports Group plc (M.A.G.):- Manchester City Council-35.5%; 9 Gtr Ken O'Toole, M.D. Cheshire East Council Manchester Airport http://www.manchesterairport.co.uk/ Manchester Airport plc Yes Manchester authorities-29%; IFM Investors- Manchester Airport 35.5% Cornwall Council Cornwall Airport Newquay http://www.newquaycornwallairport.com/ Cornwall Council (100%) Cornwall Airport Ltd Al Titterington, M.D. Yes Lands End Airport http://www.landsendairport.co.uk/ Isles of Scilly Steamship Company (100%) Lands End Airport Ltd Rob Goldsmith, CEO No http://www.scilly.gov.uk/environment- St Marys Airport, Isles of Scilly Duchy of Cornwall (100%) Theo Leisjer, C.E. -

World Commerce Review Corporate Aviation Review

AviationCorporate Review WORLD COMMERCE REVIEW THE NBAA REVIEW PUNCHING ABOVE ITS SIMON WILLIAMS CELEBRatES THE INNOVatION AND WEIGHT. THE MBAA ON THE ISLE OF MAN'S 10TH INVESTMENT HIGHLIGHTED MALta AS AN AVIatION ANNIVERSARY AS A LEADING at EBACE2018 SUccESS STORY AIRCRAFT REGISTRY THE GLOBAL TRADE PLATFORM DETAILS MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. FEEL OUR PASSION FOR PERFECTION. Tel: +356 2137 5973 www.dc-aviation.com.mt For Business Jet Handling: [email protected] For Business Jet Charter: www.worldcommercereview.com [email protected] Foreword elcome to the WCR corporate aviation ePub. www.worldcommercereview.com Our remit is to provide an interactive forum for existing users and new entrants to the sector. W Those who have integrated corporate aviation into their business plan will tell you of the productivity and profit en- hancements it can offer. They will point to the key benefit of flexibility and the ability to quickly rearrange planning and the ability to move key staff at business-critical moments and close the deal quickly and efficiently. Many will point to technologies such as video and telepresence as viable alternatives and whilst these systems are valuable and useful in their own right, they cannot offer the one to one human meetings that corporate aviation can. Many cultures in key markets express a preference for person-to-person meetings and a traditional handshake can seal the deal. In this corporate aviation offers benefits that cannot be matched. We will endeavour to show both shareholders and others with an interest in the company’s well-being in interna- tional markets that corporate aviation can help to drive new business and consolidate markets. -

FAC Interface Magazine Cover

Christmas Edition 2020 interFACe The magazine of the Farnborough Aerospace Consortium In This Issue: Member Spotlight FAC Chief FAC office closure Executive David Barnes interview in FAC Aviation Business News Chairman Sir Beagle Technology Group Page 4 Page 2 Donald Spiers Page 1 FCoT ARIC Ground Breaking The FAC Chairman Donald Spiers attended the ground breaking ceremony for the new Aerospace Research and Innovation Centre at Farnborough College of Technology at the beginning of December and gave this speech: ‘I am delighted to be here today to take part in this ground-breaking ceremony for the new Aerospace Research and Innovation Centre. Aerospace is a very important sector of the UK economy and is supported by a large number of small engineering companies, SMEs, based in the SE of England. The year 2020 has been a difficult year for Aerospace, in both operational and manufacturing, but it will bounce back strongly in 2021 and indeed the signs are already there. One of those signs is this centre, because the future is dependent on new ideas and that requires training young engineers in Research and Innovation to develop those new ideas. FCoT has always been closely involved with the aerospace sector, and indeed Virginia Barrett is a Director of the Farnborough Aerospace Consortium, the trade association for SMEs in the Aerospace sector. The Government also realised the importance of innovation in aerospace some years ago and set up the National Aerospace Technology Exploitation Programme (NATEP) to provide funding for SMEs to develop new ideas. FAC is involved in the administration of this programme and I have no doubt that engineers trained in this new facility will become involved in NATEP in the future. -

Biometrics Takes Off—Fight Between Privacy and Aviation Security Wages On

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 85 Issue 3 Article 4 2020 Biometrics Takes Off—Fight Between Privacy and Aviation Security Wages On Alexa N. Acquista Southern Methodist University, Dedman School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Alexa N. Acquista, Biometrics Takes Off—Fight Between Privacy and Aviation Security Wages On, 85 J. AIR L. & COM. 475 (2020) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol85/iss3/4 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. BIOMETRICS TAKES OFF—FIGHT BETWEEN PRIVACY AND AVIATION SECURITY WAGES ON ALEXA N. ACQUISTA* ABSTRACT In the last two decades, the Department of Homeland Secur- ity (DHS) has implemented a variety of new screening and iden- tity verification methods in U.S. airports through its various agencies such as the Transportation Security Administration (TSA) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP). In particular, biometric technology has become a focal point of aviation secur- ity advances. TSA, CBP, and even private companies have started using fingerprint, iris, and facial scans to verify travelers’ identi- ties, not only to enhance security but also to improve the travel experience. This Comment examines how DHS, its agencies, and private companies are using biometric technology for aviation security. It then considers the most common privacy concerns raised by the expanded use of biometric technology: data breaches, func- tion creep, and data sharing. -

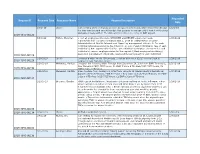

Request ID Received Date Requester Name Request Description Requested Date 2019-TSFO-00120 2019-TSFO-00124 2019-TSFO-00129 2019

Requested Request ID Received Date Requester Name Request Description Date 2/6/2019 (b)(6) I am seeking video of my bag as soon as I put it on the rack, while it travelled through 1/1/2019 the xray machine and everything else that pertains to my bag until I took it off the rack and walked away with it. The date was December 20, 2018, at BWI airport. 2019-TSFO-00120 3/8/2019 Fulton, Mismillah 1. List all employees who were APPROVED and DENIED a personal needs 1/28/2019 request/schedule exception beginning Oct. 1, 2018 at Transportation Security Administration at Norfolk International Airport by management officials. 2. For each individual listed please provide the following: a). sex of each individual b) race of each individual c) date approved/denied for each individual d) duration of request for each individual e) reason employee states for the request f) Each employee hire date g) 2019-TSFO-00124 Approving management official who approved/denied request for each individual. 1/29/2019 (b)(6) I request a video of my TSA process. I lost an amount of $2050 over a check in 1/28/2019 2019-TSFO-00129 luggage at San Francisco airport. 1/28/2019 Melendez, Maritza I request the following Video Footage from December 29, 2018 from EWR Terminal C, 1/20/2019 New Camera 8 0830-0900 hours, C1 EWR-C-Lane 4-TD-Area 0830-0900 hours, C1 2019-TSFO-00130 EWR-C-Lane 6-TD-Area 1/28/2019 Melendez, Maritza Video Footage from January 12, 2019 from cameras at Newak Liberty International 1/20/2019 Airport: 0625-0725 hours, EWR Terminal C New Camera 8 0625-0725 hours, C1 EWR- C-Lane 4-TD-Area 0625-0725 hours, C1 EWR-C-Lane 6-TD-Area 2019-TSFO-00131 1/29/2019 Brennan, Claudia FOIA request for Baltimore–Washington International Airport on the following: • Any 1/28/2019 airport access fees collected from taxis and limos broken out by month from 2017 through the most available data. -

UK Business Aviation Companies

UK Business Aviation Companies Please do not reproduce with prior permission from the Royal Aeronautical Society. Acropolis Aviation Limited Email: [email protected] Office 114-115 Web: www.catreus.co.uk Business Aviation Centre Farnborough Cello Aviation Ltd Hampshire Gill Group House GU14 6XA 140 Holyhead Road Tel: +44 (0) 1252 526530 Birmingham Email: chartersales@acropolis- B21 0AF aviation.com Tel: +44 (0) 121 507 8700 Web: www.acropolis-aviation.com Email: [email protected] Web: www.flycello.com Aeronexus Long Border Road Centreline AV Ltd Stansted Airport Bristol Airport London Bristol CM24 1RE BS48 3DP Tel: +44 (0) 1702 346852 Tel: +44 (0) 1275 474601 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Web: www.aeronexus.aero Web: www.centreline.aero Air Charter Scotland DragonFly Executive Air Charter Signature Terminal 1 The White Building Percival Way Cardiff International Airport Luton Airport Southside LU2 9NT Vale of Glamorgan Tel: +44 (0) 1357 578161 Wales Web: www.aircharterscotland.com CF62 3BD Tel: +44 (0) 1446 711144 Blu Halkin Ltd Email: [email protected] 7 Torriano Mews Web: www.dragonflyac.co.uk London NW5 2RZ Excellence Aviation Services Ltd Tel: +44 (0) 20 3086 9876 Farnborough Business Airport Web: www.halkinjet.com Hampshire GU14 6XA Bookajet Tel: +44 (0) 7860 258048 Business Aviation Centre Web: www.excellence-aviation.com Farnborough Airport Farnborough ExecuJet Europe Hampshire CPC2 Capital Park GU14 6XA Fulbourn Cambridge Catreus CB21 5XE 67a Victoria Road Tel: +44 (0) 1223 637265 Horley -

Gatwick Airport 'Runway 2' Airspace Management Options Review

A Second Runway for Gatwick Appendix A26 Airspace Gatwick Airport ‘Runway 2’ Airspace Management Options Review Final Version 31 March 2014 Prepared by NATS Services NATS Protected 2 Gatwick Airport ‘Runway 2’ Airspace Management Options Review Gatwick Airport ‘Runway 2’ Airspace Management Options Review Prepared by: NATS Services Final Version 31 March 2014 © NATS (Services) Limited 2014 All information contained within this report is deemed NATS Protectively Marked Information. NATS Protectively Marked information is being made available to GAL for the sole purpose of granting to GAL free user rights to the contents of the report for informing GAL’s RWY 2 team on finalising its ground infrastructure development strategy. NATS does not warrant the accuracy and completeness of the content and is not responsible for updating the content. The content in no way constitute formal NATS statement or recommendations on actual airspace changes required to incorporate an additional runway at Gatwick within the London TMA. Any use of or reliance on the information by GAL and third parties are entirely at your own risks. The circulation of NATS Protectively Marked information is restricted. GAL is authorised to submit NATS Protectively Marked Information contained within this report to the Airports’ Commission, however GAL should make such disclosure subject to a disclaimer that NATS Protectively Marked Information is intended to provide operational expert opinion on the general ATM management impacts (within the immediate airspace around the airport) of GAL requirements based on the ground design options (such as the requirement to manage arrival streams based upon parking position). Save for expressly permitted herewith, NATS Protectively Marked Information shall not be disclosed except with NATS’ prior permission in writing. -

Tsa Fy2015 Foia Log 2013-Tsfo-01149 4/27/2015 2014-Tsfo-00434 2/24/2015 2015-Tsfo-00001 10/2/2014 2015-Tsfo-00002 10/2/2014 2015

TSA FY2015 FOIA LOG Requester Company Request ID Received Date Requester Name Request Description Requested Date Name 2013-TSFO-01149 4/27/2015 ( b6 ) - copy of a video on August 10, 2011 of yourself at Eppley Airport in 9/13/2012 Omaha, NE and any other actions taken in this incident from TSA and airport personnel involved. 2014-TSFO-00434 2/24/2015 Udoye, Henry - USA federal publications including the entire public domain. 7/1/2014 2015-TSFO-00001 10/2/2014 Sandvik, Runa - All briefs, emails, records, and any other documents on, about, 9/30/2014 mentioning, or concerning the creation of the "TSA Randomizer" iOS app. 2015-TSFO-00002 10/2/2014 Seeber, Kristy - A copy of a current contract and winning proposal for Lockheed 9/30/2014 Martin Cooperation HSTS0108DHRM010 under the Freedom of Information Act. 2015-TSFO-00003 10/2/2014 Colley, David - Any and all documents, memoranda, notes or other records, which 9/30/2014 refer to, reflect or indicate how many individuals, if any, were contracted, interviewed or questioned based upon their carry suspicious packages or luggage through TSA security for the time period from 10:00am on September 21, 2013 to 11:59p.m., on September 21, 2013 at the Baton Rouge Metropolitan Airport. 2015-TSFO-00004 10/2/2014 McManaman, Maxine - Office of Inspection,Report of Investigation I131029, to include, but 9/30/2014 limited to the entire file, witness statements, any communication about this case, electronic or otherwise. 2015-TSFO-00005 10/2/2014 ( b6 ) - A copy of your background investigation 9/24/2014 TSA FY2015 FOIA LOG Requester Company Request ID Received Date Requester Name Request Description Requested Date Name 2015-TSFO-00007 10/3/2014 Weltin, Dan - Requested Records: 1. -

May 7,2009 Be Available in the Near Future at Http

Monlo no De porlme nf of lronsoo rt oii on Jim Lvnch, Dîrector *ruhrylaùtlthNde 2701 Prospect Avenue Brîon Schweífzer, Gov ernor PO Box 201001 Heleno MT 59620-1001 May 7,2009 Ted Mathis Gallatin Field 850 Gallatin Field Road #6 Belgrade MT 59714 Subject: Montana Aimorts Economic knpact Study 2009 Montana State Aviation System Plan Dear Ted, I am pleased to announce that the Economic Impact Study of Montana Airports has been completed. This study was a two-year collaborative eflort between the Montana Department of Transportation (MDT) Aeronautics Division, the Federal Aviation Administration, Wilbur Smith and Associates and Morrison Maierle Inc. The enclosed study is an effort to break down aviation's significant contributions in Montana and show how these impacts affect economies on a statewide and local level. Depending on your location, you may also find enclosed several copies of an individual economic summary specific to your airport. Results ofthe study clearly show that Montana's 120 public use airports are a major catalyst to our economy. Montana enplanes over 1.5 million prissengers per year at our 15 commercial service airports, half of whom are visiting tourists. The economic value of aviation is over $1.56 billion and contributes nearly 4.5 percent to our total gross state product. There arc 18,759 aviation dependent positions in Montana, accounting for four percent of the total workforce and $600 million in wages. In addition to the economic benefits, the study also highlights how Montana residents increasingly depend on aviation to support their healtþ welfare, and safety. Montana airports support critical services for medical care, agriculture, recreation, emergency access, law enforcement, and fire fighting. -

Approved Providers of the Hold Baggage NXCT

Approved providers of the hold baggage NXCT Airport Management Services Terminal Building, Inverness Airport, Inverness, IV2 7JB 01667 461 533 or 01667 461 535 Gary Stoddart [email protected] ASTACC 77 New Abbey Road,Dumfries,DG2 7LA 01387 265232 Jeff Golightly [email protected] AviationSec 6 Mill Cottages, Grindley Brook, Whitchurch, SY13 4QH 07802 221365 Andrew Hudson [email protected] Avsec Global Ltd Business Incubation Centre,University of Chichester, Bognor Regis Campus, Upper Bognor Road, Bognor Regis,West Sussex, United Kingdom, PO21 1HR Chris Barratt [email protected] Sara Gladstone [email protected] Babcock International Group Mission Critical Services Offshore Aviation, Babcock International Group, Farburn Terrace, Aberdeen Airport East, Dyce, Aberdeen , Aberdeenshire , AB21 7DT Brenda Tait [email protected] Belfast City Airport Belfast, BT3 9JH, Northern Ireland 028 9093 9093 Ray Jeffries [email protected] Bournemouth Airport Christchurch, Dorset, BH 23 6SE 01446712621 Tony Brogden [email protected] Browns UK Training Services 72 Evelyn Crescent, Sunbury Middlesex,TW16 6LZ 07841 590787 Rodger Brown [email protected] Cardiff Airport Vale of Glamorgan, Wales, CF62 3BD +44 (0) 7342 949255 Clive Parsons [email protected] CargoTRACKER More House, 514 Finchley Road, London NW11 8DD 020 8458 7720 Ron Haviv [email protected] City of Derry Airport CODA(Operations) Ltd, Airport Road, Eglinton, County Derry, BT47 3GY 028 71 81 07 84 Tracy Duffy -

TSA -Screening Partnership Program FY 2015 1St Half

Screening Partnership Program First Half, Fiscal Year 2015 June 19, 2015 Fiscal Year 2015 Report to Congress Transportation Security Administration Message from the Acting Administrator June 19, 2015 I am pleased to present the following report, “Screening Partnership Program,” for the first half of Fiscal Year (FY) 2015, prepared by the Transportation Security Administration (TSA). TSA is submitting this report pursuant to language in the Joint Explanatory Statement accompanying the FY 2015 Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act (P.L. 114-4). The report discusses TSA’s execution of the Screening Partnership Program (SPP) and the processing of SPP applications. Pursuant to congressional requirements, this report is being provided to the following Members of Congress: The Honorable John R. Carter Chairman, House Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security The Honorable Lucille Roybal-Allard Ranking Member, House Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security The Honorable John Hoeven Chairman, Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security The Honorable Jeanne Shaheen Ranking Member, Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Homeland Security Inquiries relating to this report may be directed to me at (571) 227-2801 or to the Department’s Chief Financial Officer, Chip Fulghum, at (202) 447-5751. Sincerely yours, Francis X. Taylor Acting Administrator i Screening Partnership Program First Half, Fiscal Year 2015 Table of Contents I. Legislative Language .........................................................................................................