Biometrics Takes Off—Fight Between Privacy and Aviation Security Wages On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TOWARDS BETTER PRACTICE in NATIONAL IDENTIFICATION MANAGEMENT (Guidance for Passport Issuing Authorities and National Civil Registration)

TAG/MRTD/21-WP/4 International Civil Aviation Organization 22/11/12 Revised WORKING PAPER 05/12/12 English only TECHNICAL ADVISORY GROUP ON MACHINE READABLE TRAVEL DOCUMENTS (TAG/MRTD) TWENTY-FIRST MEETING Montréal, 10 to 12 December 2012 Agenda Item 2: Activities of the NTWG TOWARDS BETTER PRACTICE IN NATIONAL IDENTIFICATION MANAGEMENT (Guidance for Passport Issuing Authorities and National Civil Registration) (Presented by the NTWG) 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 At the Twentieth Meeting of the Technical Advisory Group on Machine Readable Travel Documents, held from 7 to 9 September 2011 (TAG/MRTD/20), the ICAO Secretariat presented TAG/MRTD/20-WP/5 on the Technical Report (TR) entitled Towards Better Practice in National Identification Management . This initiative has been led by the Secretariat within the framework of the NTWG, and presents an on-going work item to expand the relevance of the MRTD Programme to today’s travel document and border security needs. 1.2 The TAG/MRTD/20 acknowledged and supported the work done on evidence of identity in the Technical Report Towards Better Practice in National Identification Management , Version 1.0, and approved the continuation of the development of the report under the responsibility of the NTWG. 2. WORK DEVELOPMENT 2.1 A subgroup of the NTWG was formed to contribute and enhance the work achieved with the TR. A few members met in Fredericksburg on 24 to 25 May 2012, significantly progressing the development of the TR. Further exchanges were held during the NTWG meeting held in Zandvoort on 7 to 11 November 2011, and via electronic means throughout this process. -

The Hidden Costs of Terrorist Watch Lists

University of Chicago Law School Chicago Unbound Journal Articles Faculty Scholarship 2013 The Hidden Costs of Terrorist Watch Lists Anya Bernstein Follow this and additional works at: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/journal_articles Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Anya Bernstein, "The Hidden Costs of Terrorist Watch Lists," 61 Buffalo Law Review 461 (2013). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Chicago Unbound. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Chicago Unbound. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BUFFALO LAW REVIEW VOLUME 61 MAY 2013 NUMBER 3 The Hidden Costs of Terrorist Watch Lists ANYA BERNSTEIN† INTRODUCTION The No Fly List, which is used to block suspected terrorists from flying, has been in use for years. But the government still appears “stymied” by the “relatively straightforward question” of what people who “believe they have been wrongly included on” that list should do.1 In recent months, courts have haltingly started to provide their own answer, giving some individuals standing to sue to remove their names or receive additional process.2 This step is particularly important as the No Fly List continues † Bigelow Fellow and Lecturer in Law, The University of Chicago Law School. J.D., Yale Law School; Ph.D., Anthropology, The University of Chicago. Thanks to Daniel Abebe, Ian Ayres, Alexander Boni-Saenz, Anthony Casey, Anjali Dalal, Nicholas Day, Bernard Harcourt, Aziz Huq, Jerry Mashaw, Jonathan Masur, Nicholas Parrillo, Victoria Schwartz, Lior Strahilevitz, Laura Weinrib, Michael Wishnie, and James Wooten for helpful commentary. -

Electronic Identification (E-ID)

EXPLAINING INTERNATIONAL IT APPLICATION LEADERSHIP: Electronic Identification Daniel Castro | September 2011 Explaining International Leadership: Electronic Identification Systems BY DANIEL CASTRO SEPTEMBER 2011 ITIF ALSO EXTENDS A SPECIAL THANKS TO THE SLOAN FOUNDATION FOR ITS GENEROUS SUPPORT FOR THIS SERIES. SEPTEMBER 2011 THE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY & INNOVATION FOUNDATION | SEPTEMBER 2011 PAGE II TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ V Introduction..................................................................................................................... 1 Background ....................................................................................................................... 1 Box 1: Electronic Passports ............................................................................................. 3 Terminology and Technology ........................................................................................... 3 Electronic Signatures, Digital Signatures and Digital Certificates ............................... 3 Identification, Authentication and Signing ................................................................ 4 Benefits of e-ID Systems ............................................................................................ 5 Electronic Identification Systems: Deployment and Use .............................................. 6 Country Profiles ............................................................................................................. -

Denmark, Norway and Sweden Hansson

Nordic countries: Denmark, Norway and Sweden Hansson, Kristofer; Lundin, Susanne 2010 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Hansson, K., & Lundin, S. (2010). Nordic countries: Denmark, Norway and Sweden. [Publisher information missing]. http://www.cit-part.at/Deliverable3_final.pdf Total number of authors: 2 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 CIT-PART Deliverable 3 Overview on XTP policies and related TA/PTA procedures Nik Brown, Siân Beynon-Jones (Eds.) With contributions by Agnes Allansdottir, Meaghan Brierley, Edna F. Einsiedel, Erich Griessler, Kristofer Hansson, Mavis Jones, Daniel Lehner, Susanne Lundin, Anna Pichelstorfer & Anna Szyma The project ―Impact of Citizen Participation on Decision-Making in a Knowledge Intensive Policy Field‖ (CIT-PART), Contract Number: SSH-CT-2008-225327, is funded by the European Commission within the 7th Framework Programme for Research – Socioeconomic Sciences and Humanities. -

Request ID Received Date Requester Name Request Description Requested Date 2019-TSFO-00120 2019-TSFO-00124 2019-TSFO-00129 2019

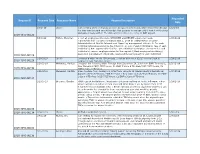

Requested Request ID Received Date Requester Name Request Description Date 2/6/2019 (b)(6) I am seeking video of my bag as soon as I put it on the rack, while it travelled through 1/1/2019 the xray machine and everything else that pertains to my bag until I took it off the rack and walked away with it. The date was December 20, 2018, at BWI airport. 2019-TSFO-00120 3/8/2019 Fulton, Mismillah 1. List all employees who were APPROVED and DENIED a personal needs 1/28/2019 request/schedule exception beginning Oct. 1, 2018 at Transportation Security Administration at Norfolk International Airport by management officials. 2. For each individual listed please provide the following: a). sex of each individual b) race of each individual c) date approved/denied for each individual d) duration of request for each individual e) reason employee states for the request f) Each employee hire date g) 2019-TSFO-00124 Approving management official who approved/denied request for each individual. 1/29/2019 (b)(6) I request a video of my TSA process. I lost an amount of $2050 over a check in 1/28/2019 2019-TSFO-00129 luggage at San Francisco airport. 1/28/2019 Melendez, Maritza I request the following Video Footage from December 29, 2018 from EWR Terminal C, 1/20/2019 New Camera 8 0830-0900 hours, C1 EWR-C-Lane 4-TD-Area 0830-0900 hours, C1 2019-TSFO-00130 EWR-C-Lane 6-TD-Area 1/28/2019 Melendez, Maritza Video Footage from January 12, 2019 from cameras at Newak Liberty International 1/20/2019 Airport: 0625-0725 hours, EWR Terminal C New Camera 8 0625-0725 hours, C1 EWR- C-Lane 4-TD-Area 0625-0725 hours, C1 EWR-C-Lane 6-TD-Area 2019-TSFO-00131 1/29/2019 Brennan, Claudia FOIA request for Baltimore–Washington International Airport on the following: • Any 1/28/2019 airport access fees collected from taxis and limos broken out by month from 2017 through the most available data. -

Biometrics Technology: Understanding Dynamics Influencing Adoption for Control of Identification Deception Within Nigeria Gideon U

Walden University ScholarWorks Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection 1-1-2011 Biometrics Technology: Understanding Dynamics Influencing Adoption for Control of Identification Deception Within Nigeria Gideon U. Nwatu Walden University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations Part of the Databases and Information Systems Commons, and the Public Policy Commons This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Walden University COLLEGE OF MANAGEMENT AND TECHNOLOGY This is to certify that the doctoral dissertation by Gideon U. Nwatu has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the review committee have been made. Review Committee Dr. Raghu Korrapati, Committee Chairperson, Applied Management and Decision Sciences Faculty Dr. Stephanie Lyncheski, Committee Member, Applied Management and Decision Sciences Faculty Dr. Walter McCollum, University Reviewer Applied Management and Decision Sciences Faculty Chief Academic Officer David Clinefelter, Ph.D. Walden University 2011 © Gideon U. Nwatu, 2011 Abstract One of the objectives of any government is the establishment of an effective solution to significantly control crime. Identity fraud in Nigeria has generated global attention and negative publicity toward its citizens. The research problem addressed in this study was the lack of understanding of the dynamics that influenced the adoption and usability of biometrics technology for reliable identification and authentication to control identity deception. -

Surveillance in Society Grahame Danby

1129 words Key Issues for the New Parliament 2010 SECURITY AND LIBERTY House of Commons Library Research Surveillance in society Grahame Danby The effective and proportionate use of surveillance and state databases is a delicate balancing act Richard Thomas, the former Information REGULATING SURVEILLANCE data or the methods of acquisition compromise LEGISLATION SUMMARY Commissioner, once famously remarked The Regulation of Investigatory Powers Act this separation? that the British people were in danger of 2000 (RIPA) controls, among other things, One proposal, subsequently abandoned on Human Rights Act 1998: A qualified “sleep walking into a surveillance society”. covert surveillance. Together with associated privacy grounds, was to store communications right to privacy. Any intrusion should be Many civil liberty groups would argue we secondary legislation and codes of practice, it data in a centralised government database. An proportionate. have now woken up in one. Others might, provides a framework designed to ensure that alternative would be to impose requirements Data Protection Act 1998: Disclosure pointedly, retort that as long as surveillance public authorities comply with the European on internet service providers to keep extra data and retention of personal data must be is deployed democratically by people always Convention on Human Rights. in a way that would make it easily accessible – fair. Exemptions apply. above reproach, if you have nothing to hide Could formalising surveillance powers particularly by law enforcement agencies and Regulation of Investigatory Powers you should never have anything to fear. lower the threshold for using them? How the security services. A Communications Data Act 2000: An authorisation framework for Surveillance, in its many forms, is undoubtedly can proportionality be factored in reliably? Bill, mooted in the last Parliament, would be various surveillance activities by specified an important tool in combating terrorism and Concerns that some local authorities have needed to implement this. -

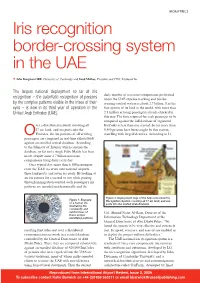

Iris Recognition Border-Crossing System in the UAE

BIOMETRICS Iris recognition border-crossing system in the UAE ❖ John Daugman OBE, University of Cambridge and Imad Malhas, President and CEO, IrisGuard Inc. The largest national deployment so far of iris daily number of iris cross-comparisons performed recognition – the automatic recognition of persons under the UAE expellee tracking and border- by the complex patterns visible in the irises of their crossing control system is about 2.7 billion. It is the eyes – is now in its third year of operation in the first system of its kind in the world, with more than United Arab Emirates (UAE). 2.1 million arriving passengers already checked in this way. The time required for each passenger to be compared against the full database of registered ver a distributed network involving all IrisCodes is less than one second. So far more than 17 air, land, and sea ports into the 9,500 persons have been caught by this system, OEmirates, the iris patterns of all arriving travelling with forged identities. According to Lt. passengers are compared in real-time exhaustively against an enrolled central database. According to the Ministry of Interior which controls the database, so far not a single False Match has been made, despite some 2.7 billion iris cross- comparisons being done every day. On a typical day, more than 6,500 passengers enter the UAE via seven international airports, three land ports, and seven sea ports. By looking at an iris camera for a second or two while passing through immigration control, each passenger's iris patterns are encoded mathematically and the Figure 2: Deployment map of the fully networked Iris Figure 1: Example Recognition System covering all 17 air, land, and sea of a human iris, ports into the United Arab Emirates illustrating the complexity and randomness of Col. -

Tsa Fy2015 Foia Log 2013-Tsfo-01149 4/27/2015 2014-Tsfo-00434 2/24/2015 2015-Tsfo-00001 10/2/2014 2015-Tsfo-00002 10/2/2014 2015

TSA FY2015 FOIA LOG Requester Company Request ID Received Date Requester Name Request Description Requested Date Name 2013-TSFO-01149 4/27/2015 ( b6 ) - copy of a video on August 10, 2011 of yourself at Eppley Airport in 9/13/2012 Omaha, NE and any other actions taken in this incident from TSA and airport personnel involved. 2014-TSFO-00434 2/24/2015 Udoye, Henry - USA federal publications including the entire public domain. 7/1/2014 2015-TSFO-00001 10/2/2014 Sandvik, Runa - All briefs, emails, records, and any other documents on, about, 9/30/2014 mentioning, or concerning the creation of the "TSA Randomizer" iOS app. 2015-TSFO-00002 10/2/2014 Seeber, Kristy - A copy of a current contract and winning proposal for Lockheed 9/30/2014 Martin Cooperation HSTS0108DHRM010 under the Freedom of Information Act. 2015-TSFO-00003 10/2/2014 Colley, David - Any and all documents, memoranda, notes or other records, which 9/30/2014 refer to, reflect or indicate how many individuals, if any, were contracted, interviewed or questioned based upon their carry suspicious packages or luggage through TSA security for the time period from 10:00am on September 21, 2013 to 11:59p.m., on September 21, 2013 at the Baton Rouge Metropolitan Airport. 2015-TSFO-00004 10/2/2014 McManaman, Maxine - Office of Inspection,Report of Investigation I131029, to include, but 9/30/2014 limited to the entire file, witness statements, any communication about this case, electronic or otherwise. 2015-TSFO-00005 10/2/2014 ( b6 ) - A copy of your background investigation 9/24/2014 TSA FY2015 FOIA LOG Requester Company Request ID Received Date Requester Name Request Description Requested Date Name 2015-TSFO-00007 10/3/2014 Weltin, Dan - Requested Records: 1. -

Implementing Biometrics to Curb Examination Malpractices in Nigeria

Section 1 – Network Systems Engineering Implementing Biometrics to Curb Examination Malpractices in Nigeria O.A.Odejobi and N.L.Clarke Centre for Information Security and Network Research, University of Plymouth, Plymouth, United Kingdom e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The problem of examinations malpractices that has been plaguing Nigeria for decades in spite of visible efforts by the stakeholders is examined in this paper. The main fundamental problems are identified as the absence of a credible identity verification system. This has an over bearing effect on knowing who should be where and at what time. Biometrics is considered as an adequate solution, with its proven achievement level in identification and verification of identities effectively answering the question- who you are. But given the peculiarity of Nigeria, there are general and solution specific requirement to be met for a successful implementation of biometrics in Nigeria. The proposed biometric solution; a smartcard based fingerprint verification technology incorporating the security strength of smartcards and the accuracy and speed of fingerprint biometrics is presented. A case for it is made, discussing the choice of technologies, cost and the views of the stakeholders. The paper concludes by looking at limitations of the presented solution and necessary future work if examination malpractices will be absolutely defeated. Keywords Examination malpractice, biometrics, identity verification, smartcard, fingerprint 1 Introduction The recent ruthless and constant upward increase in examination malpractice cases in public examinations in Nigeria, the forms of its perpetration and the increase in its sophistication at an alarming rate called for at least equal measure of sophistication in the effort to curb this menace. -

“Everyone Said No” Biometrics, HIV and Human Rights a Kenya Case Study

“Everyone said no” Biometrics, HIV and Human Rights A Kenya Case Study KELIN and the Kenya Key Populations Consortium 1 “Everyone said no” Biometrics, HIV and Human Rights, A Kenya Case Study KELIN and the Kenya Key Populations Consortium © KELIN 2018 This report was published by KELIN P O Box 112-00202, KNH Tel: +254 20 386 1596, 251 5790 Nairobi, Kenya www.kelinkenya.org Design and Layout by Impact Africa Ltd. P O Box 13776-00800, Nairobi Tel: +254 708 484 878/ +254 714 214 303 Nairobi, Kenya About KELIN KELIN is an independent Kenyan Civil Society Organization working to protect and promote health related human rights in Kenya. We do this by; Advocating for integration of human rights principles in laws, policies and administrative frameworks; facilitating access to justice in respect to violations of health related rights; training professionals and communities on rights based approaches and initiat- ing and participating in strategic partnerships to realize the right to health nationally, regionally and globally. While originally created to protect and promote HIV-related human rights, our scope has expanded to also include: • Sexual and reproductive health and rights, • Key populations, and • Women, land and property rights. Our goal is to advocate for a holistic and rights-based system of service delivery in health and for the full enjoyment of the right to health by all, including the vulnerable, marginalized, and excluded populations in these four thematic areas. About the Key Populations Consortium The key population consortium comprises networks of over 90 organizations and community repre- sentatives working with and around issues of Key Populations HIV programming namely Female and Male Sex workers (SW); People who Inject Drugs (PWIDs); and Men who have Sex with Men (MSM). -

Kenya-ID4D-Diagnostic-Webv42018

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ID4D Country Diagnostic: Kenya Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized 28370_Kenya_ID4D.indd 1 4/12/18 9:51 AM © 2016 International Bank for Reconstitution and Development/The World Bank 1818 H Street, NW, Washington, D.C., 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some Rights Reserved This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the governments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, or of any participating organization to which such privileges and immunities may apply, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permission This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. 2016.