The Romantic Period 1785-1830

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The political ideas of William Hazlitt (1778-1830) Garnett, Mark Alan How to cite: Garnett, Mark Alan (1990) The political ideas of William Hazlitt (1778-1830), Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/6186/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk ABSTRACT OF A THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY, 1990. "The Political Ideas of William Hazlitt, 1778-1830" MARK ALAN GARNETT Department of Politics, Durham University. The purpose of the thesis was to examine William Hazlitt's political thought from the viewpoint of the history of ideas. Such a study should lead to a greater appreciation of his value as a political critic. The received notion that he was a radical provided a starting-point for investigation. Hazlitt's theoretical work in philosophy and politics was found to be of interest, but his views on contemporary personalities and events are more revealing. -

Adam Mickiewicz's

Readings - a journal for scholars and readers Volume 1 (2015), Issue 2 Adam Mickiewicz’s “Crimean Sonnets” – a clash of two cultures and a poetic journey into the Romantic self Olga Lenczewska, University of Oxford The paper analyses Adam Mickiewicz’s poetic cycle ‘Crimean Sonnets’ (1826) as one of the most prominent examples of early Romanticism in Poland, setting it across the background of Poland’s troubled history and Mickiewicz’s exile to Russia. I argue that the context in which Mickiewicz created the cycle as well as the final product itself influenced the way in which Polish Romanticism developed and matured. The sonnets show an internal evolution of the subject who learns of his Romantic nature and his artistic vocation through an exploration of a foreign land, therefore accompanying his physical journey with a spiritual one that gradually becomes the main theme of the ‘Crimean Sonnets’. In the first part of the paper I present the philosophy of the European Romanticism, situate it in the Polish historical context, and describe the formal structure of the Crimean cycle. In the second part of the paper I analyse five selected sonnets from the cycle in order to demonstrate the poetic journey of the subject-artist, centred around the epistemological difference between the Classical concept of ‘knowing’ and the Romantic act of ‘exploring’. Introduction The purpose of this essay is to present Adam Mickiewicz's “Crimean Sonnets” cycle – a piece very representative of early Polish Romanticism – in the light of the social and historical events that were crucial for the rise of Romantic literature in Poland, with Mickiewicz as a prize example. -

Toward Liberalism: Politics, Poverty, and the Emotions in the 1790S Peter Denney Griffith University

Toward Liberalism: Politics, Poverty, and the Emotions in the 1790s Peter Denney Griffith University I n the volatile atmosphere of the mid-1840s, the leading exponent of Victorian liber- alism, John Stuart Mill, published an essay in the Edinburgh Review in which he rejected the assumption that political economy encompassed a “hard-hearted, unfeeling” approach Ito the question of poverty.1 Entitled “The Claims of Labour,” a major purpose of the essay was to advocate self-help as the key to improving the condition of the laboring classes. According to Mill, the promotion of self-help was an urgent matter, for there had been a revival of the belief that the situation of the poor could be ameliorated either by charity or by the redistribution of property. It was as if people had forgotten the population theory of Thomas Robert Malthus, who, beginning in the late 1790s, argued that such schemes exacerbated the problem of poverty by discouraging the laboring classes from developing qualities like restraint and industriousness that were crucial not just to their improvement but to their survival. Radical and conservative critics alike condemned Malthus both for the bleakness of his theory and for the cold, calcu- lating attitude it seemed to endorse. While understanding such criticism, Mill dismissed these detractors as the “sentimental enemies of political economy.”2 At the same time, he insisted that political economy was compatible with sympathy, if not with sentimentality. If interpreted cor- rectly, it generated a view of the poor that mixed empirical observations with positive emotions, producing a sense of optimism regarding the future of the laboring classes. -

Globalizing Bentham

Globalizing Jeremy Bentham The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Armitage, David R. 2011. Globalizing Jeremy Bentham. History of Political Thought 32(1): 63-82. Published Version http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/imp/ hpt/2011/00000032/00000001/art00004 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11211544 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP - 1 - GLOBALIZING JEREMY BENTHAM1 David Armitage2 Abstract: Jeremy Bentham’s career as a writer spanned almost seventy years, from the Seven Years’ War to the early 1830s, a period contemporaries called an age of revolutions and more recent historians have seen as a world crisis. This article traces Bentham’s developing universalism in the context of international conflict across his lifetime and in relation to his attempts to create a ‘Universal Jurisprudence’. That ambition went unachieved and his successors turned his conception of international law in more particularist direction. Going back behind Bentham’s legacies to his own writings, both published and unpublished, reveals a thinker responsive to specific events but also committed to a universalist vision that helped to make him a precociously global figure in the history of political thought. Historians of political thought have lately made two great leaps forward in expanding the scope of their inquiries. The first, the ‘international turn’, was long- 1 History of Political Thought, 32 (2011), 63-82. -

Amerian Romanticism

1800 - 1860 AMERICAN ROMANTICISM Prose Authors of the time period . Washington Irving . James Fenimore Cooper . Edgar Allan Poe . Ralph Waldo Emerson . Henry David Thoreau . Herman Melville . Nathaniel Hawthorne Poets of the time period . William Cullen Bryant . John Greenleaf Whittier . Oliver Wendell Holmes . Edgar Allan Poe . James Russell Lowell . Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Journey . The long-distance journey is part of our history, both real and fictional… - The New York Times American Romanticism . Best described as a journey away from the corruption of civilization and the limits of rational thought and toward the integrity of nature and the freedom of the imagination. Romanticism – value feeling and intuition over reason. (started in Germany – late 18th century) Characteristics of American Romanticism . Value feeling and intuition over reason . Places faith in inner experience and the power of the imagination . Shuns the artificiality of civilization and seeks unspoiled nature . Prefers youthful innocence to educated sophistication Characteristics continued . Champions individual freedom and the worth of the individual . Contemplates nature’s beauty as a path to spiritual and moral development . Looks backward to the wisdom of the past and distrusts progress . Finds beauty and truth in exotic locales, the supernatural realm and the inner world of the imagination Characteristics continued . Sees poetry as the highest expression of the imagination . Finds inspiration in myth, legend, and folk culture Romantic Escapism . Wanted to rise above boring realities. Looked for ways to accomplish this: Exotic setting in the more “natural” past or removed from the grimy and noisy industrial age. (Supernatural, legends, folklore) Gothic Novels – haunted landscapes, supernatural events, medieval castles Romantic Escapism . -

Some Recent Definitions of German Romanticism, Or the Case Against Dialectics

SOME RECENT DEFINITIONS OF GERMAN ROMANTICISM, OR THE CASE AGAINST DIALECTICS by Robert L. Kahn When the time came for me to be seriously thinking about writing this paper-and you can see from the title and description that I gave myself plenty of leeway-I was caught in a dilemma. In the beginning my plan had been simple enough: I wanted to present a report on the latest develop- ments in the scholarship of German Romanticism. As it turned out, I had believed very rashly and naively that I could carry on where Julius Peter- sen's eclectic and tolerant book Die Wesensbestimmung der deutschen Romantik (Leipzig, 1926), Josef Komer's fragmentary and unsystematic reviews in the Marginalien (Frankfurt a. M., 1950), and Franz Schultz's questioning, though irresolute, paper "Der gegenwartige Stand der Roman- tikforschungM1had left off. As a matter of fact, I wrote such an article, culminating in what I then considered to be a novel definition of German Romanticism. But the more I thought about the problem, the less I liked what I had done. It slowly dawned on me that I had been proceeding on a false course of inquiry, and eventually I was forced to reconsider several long-cherished views and to get rid of certain basic assumptions which I had come to recognize as illusory and prejudicial. It became increasingly obvious to me that as a conscientious literary historian I could not discuss new contributions to Romantic scholarship in vacuo, but that I was under an obligation to relate the spirit of these pronouncements to our own times, as much as to relate their substance to the period in question. -

Utilitarianism in the Age of Enlightenment

UTILITARIANISM IN THE AGE OF ENLIGHTENMENT This is the first book-length study of one of the most influential traditions in eighteenth-century Anglophone moral and political thought, ‘theological utilitarianism’. Niall O’Flaherty charts its devel- opment from its formulation by Anglican disciples of Locke in the 1730s to its culmination in William Paley’s work. Few works of moral and political thought had such a profound impact on political dis- course as Paley’s Principles of Moral and Political Philosophy (1785). His arguments were at the forefront of debates about the constitution, the judicial system, slavery and poverty. By placing Paley’s moral thought in the context of theological debate, this book establishes his genuine commitment to a worldly theology and to a programme of human advancement. It thus raises serious doubts about histories which treat the Enlightenment as an entirely secular enterprise, as well as those which see English thought as being markedly out of step with wider European intellectual developments. niall o’flaherty is a Lecturer in the History of European Political Thought at King’s College London. His research focuses on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century moral, political and religious thought in Britain. He has published articles on William Paley and Thomas Robert Malthus, and is currently writing a book entitled Malthus and the Discovery of Poverty. ideas in context Edited by David Armitage, Richard Bourke, Jennifer Pitts and John Robertson The books in this series will discuss the emergence of intellectual traditions and of related new disciplines. The procedures, aims and vocabularies that were generated will be set in the context of the alternatives available within the contemporary frameworks of ideas and institutions. -

Grażyna H Alkiewicz

REVIEWS the methodology used by anna roter-Bourkane, the contexts she describes and the ambition to define the concepts mentioned in the title of the book. at the same time, the authors raises questions about the aesthetics of the treatise-typical features, which in the examined book is not clearly distinguished from the genre of treaty. Key words: treatise; features of treatise; 19th century; poetry; Cyprian norwid; genology. Summary translated by Rafał Augustyn magdaleNa woźNiewsKa-działaK – Phd, assistant professor in the department of theory of Culture and interculturalism, Faculty of Humanities, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński university (uKSW) in Warsaw. author of the book Poematy narracyjne Cypriana Norwida. Konteksty literacko-kulturalne, estetyka, myśl (2014). uKSW, ul. dewajtis 5, 01-815 Warszawa; e-mail: [email protected] Grażyna H a l k i e w i c z - S o j a k – on tHE HiddEn diMEnSion oF tHE roMantiC HEritaGE doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.18290/sn.2017.35-15en Ewa Szczeglacka-Pawłowska has been consistently developing her research methodology for over a dozen years, looking for a research perspective that would allow to read the poetry of Polish romanticism in exile with respect for the achievements of several generations of editors and historians of literature, but also with emphasis on the researcher’s own, if possible original, approach. this is best evidenced by her two books: Romantyczny homo legens. Zygmunt Krasiński jako czy telnik polskich poetów [romantic homo legens. Zygmunt Krasiński as a reader of Polish poets] (Warsaw 2003, 367 pages) and Romantyzm “brulionowy” [“draft paper” romanticism] (Warsaw 2015, 580 pages). -

Donald J. Greene

Recent Studies in the Restoration and Eighteenth Century DONALD J. GREENE I IT IS instructive for any literary student, but especially for a contributor to a new scholarly journal, to browse in the early numbers of those journals that started a genera- tion ago-to read Ronald Crane's ruthless dissections, in the early PQ annual bibliographies, of Continental theses ponderously chasing the elusive abstractions "neo-classicism" and "pre-romanti- cism" through jungles of logomachy; to encounter, in RES, such wise words of Ronald McKerrow's as (1928) "Our interest now lies, not in inventing neat phrases which will serve to label these periods [of literature] and emphasize the watertight nature of their divisions, but in showing how they are interlocked one with another," or these (1934) castigating "a time when an attitude of simple faith towards the dicta of the earlier literary histories was more customary than is the rule at present, and when the pic- turesqueness of an anecdote or the ingenuity of a theory seemed too often to have been accepted as evidence of its truth." ExpeUas naturam furca, tamen usque recurrit. In 1960 (this survey attempts Ito cover late 1959 and most of 1960), were we in eighteenth- century studies as far advanced as Crane's and McKerrow's readers toward the ideal for which they strove? The tendency to compart- mentalize and isolate a period of literature-to "professionalize" it, in the worst sense of the term-seems innate in human mental sloth. To take one's notions of eighteenth-century history or philo- sophy or theology from the convenient summaries of Lecky or Leslie Stephen in Professor So-and-so's literary history is easier than to go to the original sources or to serious contemporary schol- arship in those disciplines. -

Romanticism in English Poetry

ROMANTICISM IN ENGLISH POETRY A MLiCT AHfMOTATeO BiaUOQRAPHV SUBMITTtp m PARTIAL FULFH-MENT FOR TNf AWARD OF THE OCQflEE OF of librarp aiili itifarmation i^tteme 19t344 Roll Mo. t3 LSM-17 EnroliMM No. V-1432 Undsr th* SuparvMon of STBD MUSTIIFIIUIDI (READER) DEPARTMENT OF LIBRARY A INFORMATION SCIENCE ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1994~ AIAB ^ **' r •^, '-fcv DS2708 DEDICATED TO MY LATE MOTHER CONTENTS page Acknowl edg&a&it ^ Scope and Methodology iii PART - I introduction 1 PART - II Annotated Bibliography ^^ List of Periodicals 113 PART - III Author index ^-^^ Title index 124 (i) ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to express my sincere and earnest thanks to my teacher and Supervisor . kr» S. Mustafa Zaidi, who inspite of his many pre-occupations spared his precious time to guide and inspire me at each and every step/ during the course of this investigation. His deep critical understanding of the problem helped me in conpiling this bibliography. I am highly indebted to eminent teacher professor Mohd. sabir Husain, Chairman/ Department of Liberary & Information Science/ Aligarh Muslim University Allgarh for the encourage ment that I have always received from him during the period I have been associated with the department of Library Science. I am also highly grateful to the respected teachers of my Department Mr. Al-Muzaffar Khan, Reader, Mr. shabahat Husain, Reader/ Mr. Ifasan zamarrud. Reader. They extended their full cooperation in all aspects, whatever I needed. I am also thankful to the Library staff of Maulana Azad Library, A.M.U., Aligarh, Seminar Library Department of English, AMU Aligarh, for providing all facilities that I needed for my work. -

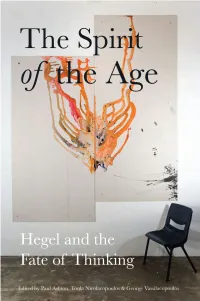

Spirit of the Age.Indb

The Spirit of the Age Anamnesis Anamnesis means remembrance or reminiscence, the collection and re- collection of what has been lost, forgotten, or effaced. It is therefore a matter of the very old, of what has made us who we are. But anamnesis is also a work that transforms its subject, always producing something new. To recollect the old, to produce the new: that is the task of Anamnesis. a re.press series The Spirit of the Age: Hegel and the Fate of Thinking Paul Ashton, Toula Nicolacopoulos and George Vassilacopoulos, editors re.press Melbourne 2008 re.press PO Box 40, Prahran, 3181, Melbourne, Australia http://www.re-press.org © re.press 2008 This work is ‘Open Access’, published under a creative commons license which means that you are free to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to the authors, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form whatsoever and that you in no way alter, transform or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without express permission of the author (or their executors) and the publisher of this volume. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. For more information see the details of the creative commons licence at this website: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.5/ British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication Data The spirit of the age : Hegel and the fate of thinking Bibliography. -

Poetic Prophetism in Romanian Romanticism

MINISTRY OF NATIONAL EDUCATION AND SCIENTIFIC RESEARCH UNIVERSITY "LUCIAN BLAGA" OF SIBIU THE INSTITUTE OF DOCTORAL STUDIES FACULTY OF LETTERS AND ARTS Poetic Prophetism in Romanian Romanticism Ph.D. Thesis -Summary- Scientific co-ordinators: Prof. univ. dr. habil. Andrei TERIAN Prof. univ. dr. Gheorghe MANOLACHE Ph.D. Student: Crina POENARIU Sibiu 2017 Contents Argument...................................................................................................................................5 Chapter One: Morphotipology of prophetism........................................................................10 1.1. Ethimology and semantic dinamics...................................................................................10 1.2. Paradigms of prophetism...................................................................................................14 1.2.1.Protoprophetism or primary prophetism.............................................................15 1.2.1.1.Hebrew prophetism...............................................................................15 1.2.1.2.Greek-Latin prophetism.........................................................................22 1.2.2.Neoprophetism or recovered prophetism............................................................28 1.3.Inter- and intraparadigmatical delimitations.......................................................................33 1.3.1.The Visionary.......................................................................................................33 1.3.2. Symbolic