The New Romantics: Romantic Themes in the Poetry of Guo Moruo and Xu Zhimo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

CIM's First Artistic Director Was Ernest Bloch, a Swiss Composer and Teacher Who Came to Cleveland from New York City

BLOCH, ERNEST (24 July 1880-15 July 1959), was an internationally known composer, conductor, and teacher recruited to found and direct the CLEVELAND INSTITUTE OF MUSIC in 1920. Bloch was born in Geneva, Switzerland. The son of Sophie (Brunschwig) and Maurice (Meyer) Bloch, a Jewish merchant, Bloch showed musical talent early and determined that he would become a composer. His teen years were marked by important study with violin and composition masters in various European cities. Between 1904 and 1916, he juggled business responsibilities with composing and conducting. In 1916 Bloch accepted a job as conductor for dancer Maud Allen's American tour. The tour collapsed after 6 weeks, but performances of his works in New York and Boston led to teaching positions in New York City. During the Cleveland years (1920-25), Bloch completed 21 works, among them the popular Concerto Grosso, which was composed for the students' orchestra at the Cleveland Institute of Music. His contributions included an institute chorus at the CLEVELAND MUSEUM OF ART, attention to pedagogy especially in composition and theory, and a concern that every student should have a direct and high-quality aesthetic experience. He taught several classes himself. After disagreements with Cleveland Institute of Music policymakers, he moved to the directorship of the San Francisco Conservatory. Following some years studying in Europe, Bloch returned to the U.S. in 1939 to teach at the Univ. of Calif.-Berkeley. He retired in 1941. His students over the years included composers Roger Sessions and HERBERT ELWELL. Bloch composed over 100 works for a variety of individual instruments and ensemble sizes and won over a dozen prestigious awards. -

New China and Its Qiaowu: the Political Economy of Overseas Chinese Policy in the People’S Republic of China, 1949–1959

1 The London School of Economics and Political Science New China and its Qiaowu: The Political Economy of Overseas Chinese policy in the People’s Republic of China, 1949–1959 Jin Li Lim A thesis submitted to the Department of International History of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, September 2016. 2 Declaration: I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of 98,700 words. 3 Abstract: This thesis examines qiaowu [Overseas Chinese affairs] policies during the PRC’s first decade, and it argues that the CCP-controlled party-state’s approach to the governance of the huaqiao [Overseas Chinese] and their affairs was fundamentally a political economy. This was at base, a function of perceived huaqiao economic utility, especially for what their remittances offered to China’s foreign reserves, and hence the party-state’s qiaowu approach was a political practice to secure that economic utility. -

Adam Mickiewicz's

Readings - a journal for scholars and readers Volume 1 (2015), Issue 2 Adam Mickiewicz’s “Crimean Sonnets” – a clash of two cultures and a poetic journey into the Romantic self Olga Lenczewska, University of Oxford The paper analyses Adam Mickiewicz’s poetic cycle ‘Crimean Sonnets’ (1826) as one of the most prominent examples of early Romanticism in Poland, setting it across the background of Poland’s troubled history and Mickiewicz’s exile to Russia. I argue that the context in which Mickiewicz created the cycle as well as the final product itself influenced the way in which Polish Romanticism developed and matured. The sonnets show an internal evolution of the subject who learns of his Romantic nature and his artistic vocation through an exploration of a foreign land, therefore accompanying his physical journey with a spiritual one that gradually becomes the main theme of the ‘Crimean Sonnets’. In the first part of the paper I present the philosophy of the European Romanticism, situate it in the Polish historical context, and describe the formal structure of the Crimean cycle. In the second part of the paper I analyse five selected sonnets from the cycle in order to demonstrate the poetic journey of the subject-artist, centred around the epistemological difference between the Classical concept of ‘knowing’ and the Romantic act of ‘exploring’. Introduction The purpose of this essay is to present Adam Mickiewicz's “Crimean Sonnets” cycle – a piece very representative of early Polish Romanticism – in the light of the social and historical events that were crucial for the rise of Romantic literature in Poland, with Mickiewicz as a prize example. -

New Trends in Mao Literature from China

Kölner China-Studien Online Arbeitspapiere zu Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Chinas Cologne China Studies Online Working Papers on Chinese Politics, Economy and Society No. 1 / 1995 Thomas Scharping The Man, the Myth, the Message: New Trends in Mao Literature From China Zusammenfassung: Dies ist die erweiterte Fassung eines früher publizierten englischen Aufsatzes. Er untersucht 43 Werke der neueren chinesischen Mao-Literatur aus den frühen 1990er Jahren, die in ihnen enthaltenen Aussagen zur Parteigeschichte und zum Selbstverständnis der heutigen Führung. Neben zahlreichen neuen Informationen über die chinesische Innen- und Außenpolitik, darunter besonders die Kampagnen der Mao-Zeit wie Großer Sprung und Kulturrevolution, vermitteln die Werke wichtige Einblicke in die politische Kultur Chinas. Trotz eindeutigen Versuchen zur Durchsetzung einer einheitlichen nationalen Identität und Geschichtsschreibung bezeugen sie auch die Existenz eines unabhängigen, kritischen Denkens in China. Schlagworte: Mao Zedong, Parteigeschichte, Ideologie, Propaganda, Historiographie, politische Kultur, Großer Sprung, Kulturrevolution Autor: Thomas Scharping ([email protected]) ist Professor für Moderne China-Studien, Lehrstuhl für Neuere Geschichte / Politik, Wirtschaft und Gesellschaft Chinas, an der Universität Köln. Abstract: This is the enlarged version of an English article published before. It analyzes 43 works of the new Chinese Mao literature from the early 1990s, their revelations of Party history and their clues for the self-image of the present leadership. Besides revealing a wealth of new information on Chinese domestic and foreign policy, in particular on the campaigns of the Mao era like the Great Leap and the Cultural Revolution, the works convey important insights into China’s political culture. In spite of the overt attempts at forging a unified national identity and historiography, they also document the existence of independent, critical thought in China. -

A Critical Analysis of the Sonnets of Charles Tenyson-Turner

RICE UNIVERSITY A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF THE SONNETS OF CHARLES TENNYSON-TURNER by Wilkes Berry A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts Houston, Texas May 1962 TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page 1. Introduction ..... 1 2. Versification 4 3. Themes and Topics 7 I. Poetry 8 II. Pessimism 11 III. Home and Patriotism 13 IV. Technological Progress 17 V. War 19 VI. Lovers ...... 23 VII. Death 27 VIII. The Passing of Time 32 IX. Birds, Beaits, and Insects 33 X. Land, Sea, and Sky 45 XI. History 5 2 4. Religion 58 5. Structure and Imagery 82 6. Conclusion 106 7. Appendix ..... 110 8. Footnotes 115 9. Bibliography . 118 INTRODUCTION Charles Tennyson-Turner was born in 1808 at Somersby, Lincolnshire. He was the second of the two older brothers of Alfred Tennyson, with whom he matriculated at Cambridge in 1828. Charles was graduated in 1832, and after his ordination in 1835 he was appointed curate of Tealby. Later the same year he became vicar of Grasby; then in 1836 he married Louisa Sellwood, sister to Emily Sellwood, who later married Alfred Tennyson. The next year he inherited several hundred acres of land from his great-uncle Samuel Turner of Caistor. At this time he assumed the additional surname of Turner which he used the rest of his life.* Shortly before his marriage Turner had overcome an addiction to opium which resulted from his using the drug to relieve neuralgic pain; however, he soon resumed the use of opium. His wife helped to free him of the habit once more, but, in so doing, she lost her own health and had to be placed under medical care. -

Amerian Romanticism

1800 - 1860 AMERICAN ROMANTICISM Prose Authors of the time period . Washington Irving . James Fenimore Cooper . Edgar Allan Poe . Ralph Waldo Emerson . Henry David Thoreau . Herman Melville . Nathaniel Hawthorne Poets of the time period . William Cullen Bryant . John Greenleaf Whittier . Oliver Wendell Holmes . Edgar Allan Poe . James Russell Lowell . Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Journey . The long-distance journey is part of our history, both real and fictional… - The New York Times American Romanticism . Best described as a journey away from the corruption of civilization and the limits of rational thought and toward the integrity of nature and the freedom of the imagination. Romanticism – value feeling and intuition over reason. (started in Germany – late 18th century) Characteristics of American Romanticism . Value feeling and intuition over reason . Places faith in inner experience and the power of the imagination . Shuns the artificiality of civilization and seeks unspoiled nature . Prefers youthful innocence to educated sophistication Characteristics continued . Champions individual freedom and the worth of the individual . Contemplates nature’s beauty as a path to spiritual and moral development . Looks backward to the wisdom of the past and distrusts progress . Finds beauty and truth in exotic locales, the supernatural realm and the inner world of the imagination Characteristics continued . Sees poetry as the highest expression of the imagination . Finds inspiration in myth, legend, and folk culture Romantic Escapism . Wanted to rise above boring realities. Looked for ways to accomplish this: Exotic setting in the more “natural” past or removed from the grimy and noisy industrial age. (Supernatural, legends, folklore) Gothic Novels – haunted landscapes, supernatural events, medieval castles Romantic Escapism . -

Resolution of the Central People's Government Committee on the Convening of the National People's Congress and Local People's Congresses

Resolution of the Central People's Government Committee on the convening of the National People's Congress and local people's congresses January 14, 1953 The Common Program of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference stipulates: "The state power of the People's Republic of China belongs to the people. The organs through which the people exercise state power are the people's congresses and governments at all levels. The people's congresses at all levels are elected by the people by universal suffrage. The people’s congresses at all levels elect the people’s governments at all levels. When the people’s congresses at all levels are not in session, the people’s governments at all levels are the organs that exercise all levels of power. The highest organ of power in the country is the National People’s Congress. The government is the highest organ for the exercise of state power.” (Article 12) The Organic Law of the Central People’s Government of the People’s Republic of China stipulates: “The government of the People’s Republic of China is a government of the People’s Congress based on the principle of democratic centralism.” (Article 2) Three years ago, when the country was first established, many revolutionary work was still underway, the masses were not fully mobilized, and the conditions for convening the National People’s Congress were not mature enough. Therefore, in accordance with Article 13 of the Common Program, the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference The first plenary session implements the functions and powers of the National People's Congress, formulates the Organic Law of the Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China, elects and delegates the functions and powers of the Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China to exercise state power. -

Tippecanoe County - Warrant Recall Data As of June 1, 2015

TIPPECANOE COUNTY - WARRANT RECALL DATA AS OF JUNE 1, 2015 Name Last Known Address at Time of Warrant Issuance ABBOTT, RANDY CARL STRAWSTOWN AVE NOBLESVILLE IN ABDUL-JABAR, HAKIMI SHEETZ STREET WEST LAFAYETTE IN ABERT, JOSEPH DEAN W 5TH ST HARDY AR ABITIA, ANGEL S DELAWARE INDIANAPOLIS IN ABRAHA, THOMAS SUNFLOWER COURT INDIANAPOLIS IN ABRAMS, SCOTT JOSEPH ABRIL, NATHEN IGNACIO S 30TH ST LAFAYETTE IN ABTIL, CHARLES HALSEY DRIVE WEST LAFAYETTE IN ABUASABEH, FAISAL B NEIL ARMSTRONG DR WEST LAFAYETTE IN ABUNDIS, JOSE DOMINGO LEE AVE COOKVILLE TN ACEBEDO, RICARDO S 17TH ST LAFAYETTE IN ACEVEDO, ERIC JAVIER OAK COURT LAFAYETTE IN ACHOR, ROBERT GENE II E COLUMBIA ST LOGANSPORT IN ACOFF, DAMON LAMARR LINDHAM CT MECHANICSBURG PA ACOSTA, ANTONIO E MAIN STREET HOOPESTON IL ACOSTA, MARGARITA ROSSVILLE IN ACOSTA, PORFIRIO DOMINGUIEZ N EARL AVE LAFAYETTE IN ADAMS JR, JOHNNY ALLAN RICHMOND CT LEBANON IN ADAMS, KENNETH A W 650 S ROSSVILLE IN ADAMS, MATTHEW R BROWN STREET LAFAYETTE IN ADAMS, PARKE SAMUEL N 26TH ST LAFAYETTE IN ADAMS, RODNEY S 8TH ST LAFAYETTE IN ADAMSON, JOSHUA PAUL BUNTING LN LAFAYETTE IN ADAMSON, RONALD LEE SUNSET RIDGE DR LAFAYETTE IN ADCOX, SCOTT M LAWN AVE WEST LAFAYETTE IN ADINA-ZADE, ABDOUSSALAM NORTH 6TH STREET LAFAYETTE IN ADITYA, SHAH W WOOD ST WEST LAFAYETTE IN ADKINS, DANIEL L HC 81 BOX 6 BALLARD WV ADKINS, JARROD LEE S 28TH ST LAFAYETTE IN ADRIANSON, MARK ANDREW BOSCUM WINGATE IN AGEE, PIERE LAMAR DANUBE INDIANAPOLIS IN AGUAS, ANTONIO N 10TH ST LAFAYETTE IN AGUILA-LOPEZ, ISAIAS S 16TH ST LAFAYETTE IN AGUILAR, FRANSICO AGUILAR, -

Some Recent Definitions of German Romanticism, Or the Case Against Dialectics

SOME RECENT DEFINITIONS OF GERMAN ROMANTICISM, OR THE CASE AGAINST DIALECTICS by Robert L. Kahn When the time came for me to be seriously thinking about writing this paper-and you can see from the title and description that I gave myself plenty of leeway-I was caught in a dilemma. In the beginning my plan had been simple enough: I wanted to present a report on the latest develop- ments in the scholarship of German Romanticism. As it turned out, I had believed very rashly and naively that I could carry on where Julius Peter- sen's eclectic and tolerant book Die Wesensbestimmung der deutschen Romantik (Leipzig, 1926), Josef Komer's fragmentary and unsystematic reviews in the Marginalien (Frankfurt a. M., 1950), and Franz Schultz's questioning, though irresolute, paper "Der gegenwartige Stand der Roman- tikforschungM1had left off. As a matter of fact, I wrote such an article, culminating in what I then considered to be a novel definition of German Romanticism. But the more I thought about the problem, the less I liked what I had done. It slowly dawned on me that I had been proceeding on a false course of inquiry, and eventually I was forced to reconsider several long-cherished views and to get rid of certain basic assumptions which I had come to recognize as illusory and prejudicial. It became increasingly obvious to me that as a conscientious literary historian I could not discuss new contributions to Romantic scholarship in vacuo, but that I was under an obligation to relate the spirit of these pronouncements to our own times, as much as to relate their substance to the period in question. -

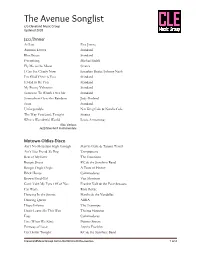

The Avenue Songlist C/O Cleveland Music Group Updated 2018

The Avenue Songlist c/o Cleveland Music Group Updated 2018 Jazz/Dinner At Last Etta James Autumn Leaves Standard Blue Bossa Standard Everything Michael Bublé Fly Me to the Moon Sinatra I Can See Clearly Now Jonathan Butler/Johnny Nash I’m Glad There is You Standard It Had to Be You Standard My Funny Valentine Standard Someone To Watch Over Me Standard Somewhere Over the Rainbow Judy Garland Soon Standard Unforgettable Nat King Cole & Natalie Cole The Way You Look Tonight Sinatra What a Wonderful World Louis Armstrong Also Various Jazz/Standard Instrumentals Motown-Oldies-Disco Ain’t No Mountain High Enough Marvin Gaye & Tammi Terrell Ain’t Too Proud To Beg Temptations Best of My Love The Emotions Boogie Shoes KC & the Sunshine Band Boogie Oogie Oogie A Taste of Honey Brick House Commodores Brown Eyed Girl Van Morrison Can’t Take My Eyes Off of You Frankie Valli & the Four Seasons Car Wash Rose Royce Dancing In the Streets Martha & the Vandellas Dancing Queen ABBA Disco Inferno The Trammps Don’t Leave Me This Way Thelma Houston Easy Commodores Fire (When We Kiss) Pointer Sisters Freeway of Love Aretha Franklin Get Down Tonight KC & the Sunshine Band ClevelandMusicGroup.com/entertainment/the-avenue 1 of 4 The Avenue Songlist c/o Cleveland Music Group Updated 2018 How Sweet It Is to Be Loved By You James Taylor I Can See Clearly Now Jonny Nash/Jonathan Butler I Can’t Help Myself Four Tops I Love the Night Life Alicia Bridges I Want You Back Jackson 5 I Will Survive Gloria Gaynor I Wish Stevie Wonder Isn’t She Lovely Stevie Wonder Jump Jive -

YAO-DISSERTATION-2016.Pdf

CONSUMING SCIENCE: A HISTORY OF SOFT DRINKS IN MODERN CHINA A Dissertation Presented to The Academic Faculty by Liang Yao In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the School of History and Sociology Georgia Institute of Technology May 2016 COPYRIGHT © 2015 BY LIANG YAO CONSUMING SCIENCE: A HISTORY OF SOFT DRINKS IN MODERN CHINA Approved by: Dr. Hanchao Lu, Advisor Dr. Laura Bier School of History and Sociology School of History and Sociology Georgia Institute of Technology Georgia Institute of Technology Dr. John Krige Dr. Kristin Stapleton chool of History and Sociology History Department Georgia Institute of Technology University at Buffalo Dr. Steven Usselman chool of History and Sociology Georgia Institute of Technology Date Approved: December 2, 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would never have finished my dissertation without the guidance, help, and support from my committee members, friends, and family. Firstly, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my advisor Professor Hanchao Lu for his caring, continuous support, and excellent intellectual guidance in all the time of research and writing of this dissertation. During my graduate study at Georgia Tech, Professor Lu guided me where and how to find dissertation sources, taught me how to express ideas and write articles like a historian. He provided me opportunities to teach history courses on my own. He also encouraged me to participate in conferences and publish articles on journals in the field. His patience and endless support helped me overcome numerous difficulties and I could not have imagined having a better advisor and mentor for my doctorial study.