Induced Heave: Correcting for Changing Sonar Draft Due to Vessel Motion by Josh Sampey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turning the Tide on Trash: Great Lakes

Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Floating marine debris in Hawaii NOAA PIFSC CRED Educators, parents, students, and Unfortunately, the ocean is currently researchers can use Turning the Tide under considerable pressure. The on Trash as they explore the serious seeming vastness of the ocean has impacts that marine debris can have on prompted people to overestimate its wildlife, the environment, our well being, ability to safely absorb our wastes. For and our economy. too long, we have used these waters as a receptacle for our trash and other Covering nearly three-quarters of the wastes. Integrating the following lessons Earth, the ocean is an extraordinary and background chapters into your resource. The ocean supports fishing curriculum can help to teach students industries and coastal economies, that they can be an important part of the provides recreational opportunities, solution. Many of the lessons can also and serves as a nurturing home for a be modified for science fair projects and multitude of marine plants and wildlife. other learning extensions. C ON T EN T S 1 Acknowledgments & History of Turning the Tide on Trash 2 For Educators and Parents: How to Use This Learning Guide UNIT ONE 5 The Definition, Characteristics, and Sources of Marine Debris 17 Lesson One: Coming to Terms with Marine Debris 20 Lesson Two: Trash Traits 23 Lesson Three: A Degrading Experience 30 Lesson Four: Marine Debris – Data Mining 34 Lesson Five: Waste Inventory 38 Lesson -

A Numerical Study of the Long- and Short-Term Temperature Variability and Thermal Circulation in the North Sea

JANUARY 2003 LUYTEN ET AL. 37 A Numerical Study of the Long- and Short-Term Temperature Variability and Thermal Circulation in the North Sea PATRICK J. LUYTEN Management Unit of the Mathematical Models, Brussels, Belgium JOHN E. JONES AND ROGER PROCTOR Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory, Bidston, United Kingdom (Manuscript received 3 January 2001, in ®nal form 4 April 2002) ABSTRACT A three-dimensional numerical study is presented of the seasonal, semimonthly, and tidal-inertial cycles of temperature and density-driven circulation within the North Sea. The simulations are conducted using realistic forcing data and are compared with the 1989 data of the North Sea Project. Sensitivity experiments are performed to test the physical and numerical impact of the heat ¯ux parameterizations, turbulence scheme, and advective transport. Parameterizations of the surface ¯uxes with the Monin±Obukhov similarity theory provide a relaxation mechanism and can partially explain the previously obtained overestimate of the depth mean temperatures in summer. Temperature strati®cation and thermocline depth are reasonably predicted using a variant of the Mellor±Yamada turbulence closure with limiting conditions for turbulence variables. The results question the common view to adopt a tuned background scheme for internal wave mixing. Two mechanisms are discussed that describe the feedback of the turbulence scheme on the surface forcing and the baroclinic circulation, generated at the tidal mixing fronts. First, an increased vertical mixing increases the depth mean temperature in summer through the surface heat ¯ux, with a restoring mechanism acting during autumn. Second, the magnitude and horizontal shear of the density ¯ow are reduced in response to a higher mixing rate. -

Prioritization of Oxygen Delivery During Elevated Metabolic States

Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology 144 (2004) 215–224 Eat and run: prioritization of oxygen delivery during elevated metabolic states James W. Hicks∗, Albert F. Bennett Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697, USA Accepted 25 May 2004 Abstract The principal function of the cardiopulmonary system is the matching of oxygen and carbon dioxide transport to the metabolic V˙ requirements of different tissues. Increased oxygen demands ( O2 ), for example during physical activity, result in a rapid compensatory increase in cardiac output and redistribution of blood flow to the appropriate skeletal muscles. These cardiovascular changes are matched by suitable ventilatory increments. This matching of cardiopulmonary performance and metabolism during activity has been demonstrated in a number of different taxa, and is universal among vertebrates. In some animals, large V˙ increments in aerobic metabolism may also be associated with physiological states other than activity. In particular, O2 may increase following feeding due to the energy requiring processes associated with prey handling, digestion and ensuing protein V˙ V˙ synthesis. This large increase in O2 is termed “specific dynamic action” (SDA). In reptiles, the increase in O2 during SDA may be 3–40-fold above resting values, peaking 24–36 h following ingestion, and remaining elevated for up to 7 days. In addition to the increased metabolic demands, digestion is associated with secretion of H+ into the stomach, resulting in a large metabolic − alkalosis (alkaline tide) and a near doubling in plasma [HCO3 ]. During digestion then, the cardiopulmonary system must meet the simultaneous challenges of an elevated oxygen demand and a pronounced metabolic alkalosis. -

Arenicola Marina During Low Tide

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published June 15 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Sulfide stress and tolerance in the lugworm Arenicola marina during low tide Susanne Volkel, Kerstin Hauschild, Manfred K. Grieshaber Institut fiir Zoologie, Lehrstuhl fur Tierphysiologie, Heinrich-Heine-Universitat, Universitatsstr. 1, D-40225 Dusseldorf, Germany ABSTRACT: In the present study environmental sulfide concentrations in the vicinity of and within burrows of the lugworm Arenicola marina during tidal exposure are presented. Sulfide concentrations in the pore water of the sediment ranged from 0.4 to 252 pM. During 4 h of tidal exposure no significant changes of pore water sulfide concentrations were observed. Up to 32 pM sulfide were measured in the water of lugworm burrows. During 4 h of low tide the percentage of burrows containing sulfide increased from 20 to 50% in July and from 36 to 77% in October A significant increase of median sulfide concentrations from 0 to 14.5 pM was observed after 5 h of emersion. Sulfide and thiosulfate concentrations in the coelomic fluid and succinate, alanopine and strombine levels in the body wall musculature of freshly caught A. marina were measured. During 4 h of tidal exposure in July the percentage of lugworms containing sulfide and maximal sulfide concentrations increased from 17 % and 5.4 pM to 62% and 150 pM, respectively. A significant increase of median sulfide concentrations was observed after 2 and 3 h of emersion. In October, changes of sulfide concentrations were less pronounced. Median thiosulfate concentrations were 18 to 32 FM in July and 7 to 12 ~.IMin October No significant changes were observed during tidal exposure. -

POLÍTICA DE DIVERSIDADE E INCLUSÃO Sumário

POLÍTICA DE DIVERSIDADE E INCLUSÃO Sumário 5 Diversidade para combater as desigualdades 9 O Comitê de Diversidade e Inclusão 11 Entendendo um pouco sobre preconceito, discriminação, opressão estrutural, diversidade e inclusão 23 Quais temas serão tratados na Política de Diversidade e Inclusão da Fundação Tide Setubal? 39 Fundação Tide Setubal: princípios e compromissos 49 Canais de acolhimento 51 Referências Dezembro, 2020 Diversidade para combater as 1 desigualdades A Fundação Tide Setubal tem como missão “fomentar iniciativas que promovam a justiça social e o desenvol- vimento sustentável de periferias urbanas e contribuam para o enfrentamento das desigualdades socioespaciais das grandes cidades, em articulação com diversos agen- tes da sociedade civil, de instituições de pesquisa, do Estado e do mercado”. O uso do termo desigualdades, no plural, implica reconhecer que a vida dos sujeitos é atravessada não apenas pelas diferenças econômicas, mas também por uma série de fatores estruturais carac- terísticos de nossa sociedade que impactam a capacida- de das pessoas de viver e exercer seus direitos de forma plena. A discriminação e o preconceito sofridos por gru- pos minorizados também são vetores de exclusão social e contribuem para a reprodução e o aprofundamento do abismo social que separa incluídos e excluídos no Brasil. POLÍTICA DE DIVERSIDADE E INCLUSÃO 6 É com base nesse compromisso de combater as de- sigualdades em todas as suas formas que a Fundação apresenta esta Política de Diversidade e Inclusão. Nela, ficam estabelecidas as regras e compromissos que de- vem pautar a atuação de nossas colaboradoras e cola- boradores no sentido de combater ativamente todas as formas de discriminação e preconceito e promover a inclusão de todas as pessoas, independentemente de raça, gênero, orientação sexual, identidade de gênero, capacidade e origem nacional ou territorial. -

Subsurface Dinoflagellate Populations, Frontal Blooms and the Formation of Red Tide in the Southern Benguela Upwelling System

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 172: 253-264. 1998 Published October 22 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Subsurface dinoflagellate populations, frontal blooms and the formation of red tide in the southern Benguela upwelling system G. C. Pitcher*,A. J. Boyd, D. A. Horstman, B. A. Mitchell-Innes Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Private Bag X2, Rogge Bay 8012, Cape Town. South Africa ABSTRACT- The West Coast of South Africa is often subjected to problems associated with red tides which are usually attributed to blooms of migratory dinoflagellates. This study investigates the cou- pling between the physical environment and the biological behaviour and physiological adaptation of dinoflagellates in an attempt to understand bloom development, maintenance and decline. Widespread and persistent subsurface dinoflagellate populations domlnate the stratified waters of the southern Benguela during the latter part of the upwelling season. Chlorophyll concentrations as high as 50 mg m-3 are associated with the the]-mocline at approximately 20 m depth but photosynthesis in this region is restricted by low light. The subsurface population is brought to the surface in the region of the upwelling front. Here increased light levels are responsible for enhanced production, in some instances exceeding 80 mgC rn.' h ', and resulting in dense dinoflagellate concentrations in and around the uplifted thermocline. Under particular wind and current conditions these frontal bloon~sare trans- ported and accumulated inshore and red tides are formed. KEY WORDS: Dinoflagellates Subsurface populations . Frontal bloolns Red tide - Upwelling systems INTRODUCTION Pitcher 1996), or from physical damage, such as the clogging of fish gills (Grindley & Nel 1968, Brown et al. -

Hydrographic Surveys Specifications and Deliverables

HYDROGRAPHIC SURVEYS SPECIFICATIONS AND DELIVERABLES March 2019 U.S. Department of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Ocean Service Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................1 1.1 Change Management ............................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2 Changes from April 2018 ...................................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Definitions ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 1.3.1 Hydrographer ................................................................................................................................................. 4 1.3.2 Navigable Area Survey .................................................................................................................................. 4 1.4 Pre-Survey Assessment ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.5 Environmental Compliance .................................................................................................................................. 5 1.6 Dangers to Navigation .......................................................................................................................................... -

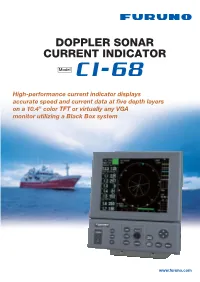

Doppler Sonar Current Indicator 8

DOPPLER SONAR CURRENT INDICATOR 8 Model High-performance current indicator displays accurate speed and current data at five depth layers on a 10.4" color TFT or virtually any VGA monitor utilizing a Black Box system www.furuno.com Obtain highly accurate water current measurements using FURUNO’s reliable acoustic technology. The FURUNO CI-68 is a Doppler Sonar Current The absolute movements of tide Indicator designed for various types of fish and measuring layers are displayed in colors. hydrographic survey vessels. The CI-68 displays tide speed and direction at five depth layers and ship’s speed on a high defi- nition 10.4” color LCD. Using this information, you can predict net shape and plan when to throw your net. Tide vector for Layer 1 The CI-68 has a triple-beam emission system for providing highly accurate current measurement. This system greatly reduces the effects of the Tide vector for Layer 2 rolling, pitching and heaving motions, providing a continuous display of tide information. When ground (bottom) reference is not available Tide vector for Layer 3 acoustically in deep water, the CI-68 can provide true tide current information by receiving position and speed data from a GPS navigator and head- ing data from the satellite (GPS) compass SC- 50/110 or gyrocompass. In addition, navigation Tide vector for Layer 4 information, including position, course and ship ’s track, can also be displayed The CI-68 consists of a display unit, processor Tide vector for Layer 5 unit and transducer. The control unit and display unit can be installed separately for flexible instal- lation. -

Time-Variable Refraction of the Internal Tide at the Hawaiian Ridge

Portland State University PDXScholar Civil and Environmental Engineering Faculty Publications and Presentations Civil and Environmental Engineering 2-2014 Time-Variable Refraction of the Internal Tide at the Hawaiian Ridge Edward D. Zaron Portland State University, [email protected] Gary D. Egbert Oregon State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/cengin_fac Part of the Civil Engineering Commons, and the Environmental Engineering Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Citation Details Zaron, E. D., & Egbert, G. D. (2014). Time-Variable Refraction of the Internal Tide at the Hawaiian Ridge. Journal Of Physical Oceanography, 44(2), 538-557. This Article is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Civil and Environmental Engineering Faculty Publications and Presentations by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. 538 JOURNAL OF PHYSICAL OCEANOGRAPHY VOLUME 44 Time-Variable Refraction of the Internal Tide at the Hawaiian Ridge EDWARD D. ZARON Portland State University, Portland, Oregon GARY D. EGBERT Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon (Manuscript received 14 December 2012, in final form 5 September 2013) ABSTRACT The interaction of the dominant semidiurnal M2 internal tide with the large-scale subtidal flow is examined in an ocean model by propagating the tide through an ensemble of background fields in a domain centered on the Hawaiian Ridge. The background fields are taken from the Simple Ocean Data Assimilation (SODA) ocean analysis, at 2-month intervals from 1992 through 2001. Tides are computed with the Primitive Equation Z-coordinate Harmonic Analysis of Tides (PEZ-HAT) model by 14-day integrations using SODA initial conditions and M2 tidal forcing. -

Lecture 1: Introduction to Ocean Tides

Lecture 1: Introduction to ocean tides Myrl Hendershott 1 Introduction The phenomenon of oceanic tides has been observed and studied by humanity for centuries. Success in localized tidal prediction and in the general understanding of tidal propagation in ocean basins led to the belief that this was a well understood phenomenon and no longer of interest for scientific investigation. However, recent decades have seen a renewal of interest for this subject by the scientific community. The goal is now to understand the dissipation of tidal energy in the ocean. Research done in the seventies suggested that rather than being mostly dissipated on continental shelves and shallow seas, tidal energy could excite far traveling internal waves in the ocean. Through interaction with oceanic currents, topographic features or with other waves, these could transfer energy to smaller scales and contribute to oceanic mixing. This has been suggested as a possible driving mechanism for the thermohaline circulation. This first lecture is introductory and its aim is to review the tidal generating mechanisms and to arrive at a mathematical expression for the tide generating potential. 2 Tide Generating Forces Tidal oscillations are the response of the ocean and the Earth to the gravitational pull of celestial bodies other than the Earth. Because of their movement relative to the Earth, this gravitational pull changes in time, and because of the finite size of the Earth, it also varies in space over its surface. Fortunately for local tidal prediction, the temporal response of the ocean is very linear, allowing tidal records to be interpreted as the superposition of periodic components with frequencies associated with the movements of the celestial bodies exerting the force. -

Brown Tidetide —— Anan Overviewoverview

New York Report #1 March 1998 BROWNBROWN TIDETIDE —— ANAN OVERVIEWOVERVIEW Brown tides are part of growing world-wide incidences of harmful algal blooms (HAB) which are caused by a proliferation of single- celled marine plants called phytoplankton. One species of phytoplankton, the microscopic alga Aureococcus anophagefferens (or-ee-oh-KAHKAH-kus ah-no-fah-JEFJEF-fer-ens) may bloom in such densities that the water turns dark brown, a condition known as “brown tide.” In 1985, severe brown tides were first reported in the Peconic Bays of eastern Long Island, Mass. New York, in Narragansett Bay, Rhode Island and possibly in Rhode Barnegat Bay, New Jersey. Since then, brown tide has Island intermittently occurred with variable intensity in Barnegat Bay and in the bays of Long Island. Connecticut New Narragansett York Bay Locations of BROWN TIDE > .50 million cells / ml NJ, NY & RI Peconic Bays > .25 million cells / ml Great South Brown tide has had particularly detrimental effects Bay on the Peconic Bay ecosystem and the economy of eastern Long Island. During intense bloom conditions, densities of the brown tide organism can approach two million cells per milliliter. These numbers far surpass typical New mixed phytoplankton densities of 100 to 100,000 in Jersey that same volume. Eelgrass beds which serve as spawning and nursery grounds for shellfish and finfish may have Barnegat been adversely impacted by decreased light penetration, Bay at least in part, due to brown tide blooms. The Peconic estuary bay scallop industry, at one point worth almost $2 million annually, was virtually eradicated to a dockside value of merely a few thousand dollars. -

The Wind and the Waves

The wind and the waves The windway Wave wars Graveyards Conflicting seas 17 The windway Sept-Îles Swell and wind waves Waves that have been formed elsewhere or before the wind - “We have to cross to Anticosti today, or we'll have trouble changed direction are called swell. The swell can be an indication tomorrow. They're calling for 30 knot winds tomorrow and the of approaching winds. sea will be too high for my liking. Sailing is a lot of fun, but you If the waves are flowing in the same direction as the wind, how- need strong nerves.” ever, you are looking at wind waves. If the wind should shift, you will encounter cross seas Fetch If there were never any wind, the St Lawrence would be a gigantic mirror, rising and falling with the tides. But that is not the case at all. Fetch: 50 nautical miles The St Lawrence is a vast surface that can be whipped up into Duration: 6 hours violent seas depending on the direction, duration and speed of the wind. Fetch is the distance over which the wind has been blowing from the same direction. The longer the fetch, the higher and longer WIND 15 KNOTS = WAVES 1.5 METRES = LENGTH 25 METRES the waves. After 12 hours at the same speed, though, the wind has almost no effect on the waves, except that it may cause them to lengthen, distance permitting. WIND 25 KNOTS = WAVES 3 METRES = LENGTH 32 METRES Since the fetch is limited on the St Lawrence, the waves cannot lengthen as much as they do out in the open ocean, so they often become very steep.