Upwelling-Downwelling Sequences in the Generation of Red Tides in a Coastal Upwelling System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turning the Tide on Trash: Great Lakes

Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Floating marine debris in Hawaii NOAA PIFSC CRED Educators, parents, students, and Unfortunately, the ocean is currently researchers can use Turning the Tide under considerable pressure. The on Trash as they explore the serious seeming vastness of the ocean has impacts that marine debris can have on prompted people to overestimate its wildlife, the environment, our well being, ability to safely absorb our wastes. For and our economy. too long, we have used these waters as a receptacle for our trash and other Covering nearly three-quarters of the wastes. Integrating the following lessons Earth, the ocean is an extraordinary and background chapters into your resource. The ocean supports fishing curriculum can help to teach students industries and coastal economies, that they can be an important part of the provides recreational opportunities, solution. Many of the lessons can also and serves as a nurturing home for a be modified for science fair projects and multitude of marine plants and wildlife. other learning extensions. C ON T EN T S 1 Acknowledgments & History of Turning the Tide on Trash 2 For Educators and Parents: How to Use This Learning Guide UNIT ONE 5 The Definition, Characteristics, and Sources of Marine Debris 17 Lesson One: Coming to Terms with Marine Debris 20 Lesson Two: Trash Traits 23 Lesson Three: A Degrading Experience 30 Lesson Four: Marine Debris – Data Mining 34 Lesson Five: Waste Inventory 38 Lesson -

A Numerical Study of the Long- and Short-Term Temperature Variability and Thermal Circulation in the North Sea

JANUARY 2003 LUYTEN ET AL. 37 A Numerical Study of the Long- and Short-Term Temperature Variability and Thermal Circulation in the North Sea PATRICK J. LUYTEN Management Unit of the Mathematical Models, Brussels, Belgium JOHN E. JONES AND ROGER PROCTOR Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory, Bidston, United Kingdom (Manuscript received 3 January 2001, in ®nal form 4 April 2002) ABSTRACT A three-dimensional numerical study is presented of the seasonal, semimonthly, and tidal-inertial cycles of temperature and density-driven circulation within the North Sea. The simulations are conducted using realistic forcing data and are compared with the 1989 data of the North Sea Project. Sensitivity experiments are performed to test the physical and numerical impact of the heat ¯ux parameterizations, turbulence scheme, and advective transport. Parameterizations of the surface ¯uxes with the Monin±Obukhov similarity theory provide a relaxation mechanism and can partially explain the previously obtained overestimate of the depth mean temperatures in summer. Temperature strati®cation and thermocline depth are reasonably predicted using a variant of the Mellor±Yamada turbulence closure with limiting conditions for turbulence variables. The results question the common view to adopt a tuned background scheme for internal wave mixing. Two mechanisms are discussed that describe the feedback of the turbulence scheme on the surface forcing and the baroclinic circulation, generated at the tidal mixing fronts. First, an increased vertical mixing increases the depth mean temperature in summer through the surface heat ¯ux, with a restoring mechanism acting during autumn. Second, the magnitude and horizontal shear of the density ¯ow are reduced in response to a higher mixing rate. -

Prioritization of Oxygen Delivery During Elevated Metabolic States

Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology 144 (2004) 215–224 Eat and run: prioritization of oxygen delivery during elevated metabolic states James W. Hicks∗, Albert F. Bennett Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697, USA Accepted 25 May 2004 Abstract The principal function of the cardiopulmonary system is the matching of oxygen and carbon dioxide transport to the metabolic V˙ requirements of different tissues. Increased oxygen demands ( O2 ), for example during physical activity, result in a rapid compensatory increase in cardiac output and redistribution of blood flow to the appropriate skeletal muscles. These cardiovascular changes are matched by suitable ventilatory increments. This matching of cardiopulmonary performance and metabolism during activity has been demonstrated in a number of different taxa, and is universal among vertebrates. In some animals, large V˙ increments in aerobic metabolism may also be associated with physiological states other than activity. In particular, O2 may increase following feeding due to the energy requiring processes associated with prey handling, digestion and ensuing protein V˙ V˙ synthesis. This large increase in O2 is termed “specific dynamic action” (SDA). In reptiles, the increase in O2 during SDA may be 3–40-fold above resting values, peaking 24–36 h following ingestion, and remaining elevated for up to 7 days. In addition to the increased metabolic demands, digestion is associated with secretion of H+ into the stomach, resulting in a large metabolic − alkalosis (alkaline tide) and a near doubling in plasma [HCO3 ]. During digestion then, the cardiopulmonary system must meet the simultaneous challenges of an elevated oxygen demand and a pronounced metabolic alkalosis. -

Arenicola Marina During Low Tide

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published June 15 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Sulfide stress and tolerance in the lugworm Arenicola marina during low tide Susanne Volkel, Kerstin Hauschild, Manfred K. Grieshaber Institut fiir Zoologie, Lehrstuhl fur Tierphysiologie, Heinrich-Heine-Universitat, Universitatsstr. 1, D-40225 Dusseldorf, Germany ABSTRACT: In the present study environmental sulfide concentrations in the vicinity of and within burrows of the lugworm Arenicola marina during tidal exposure are presented. Sulfide concentrations in the pore water of the sediment ranged from 0.4 to 252 pM. During 4 h of tidal exposure no significant changes of pore water sulfide concentrations were observed. Up to 32 pM sulfide were measured in the water of lugworm burrows. During 4 h of low tide the percentage of burrows containing sulfide increased from 20 to 50% in July and from 36 to 77% in October A significant increase of median sulfide concentrations from 0 to 14.5 pM was observed after 5 h of emersion. Sulfide and thiosulfate concentrations in the coelomic fluid and succinate, alanopine and strombine levels in the body wall musculature of freshly caught A. marina were measured. During 4 h of tidal exposure in July the percentage of lugworms containing sulfide and maximal sulfide concentrations increased from 17 % and 5.4 pM to 62% and 150 pM, respectively. A significant increase of median sulfide concentrations was observed after 2 and 3 h of emersion. In October, changes of sulfide concentrations were less pronounced. Median thiosulfate concentrations were 18 to 32 FM in July and 7 to 12 ~.IMin October No significant changes were observed during tidal exposure. -

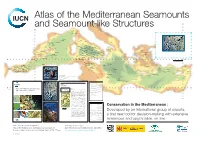

Atlas of the Mediterranean Seamounts and Seamount-Like Structures

Atlas of the Mediterranean Seamounts and Seamount-like Structures ULISSE 44 N JANUA S.LUCIA SPINOLA OCCHIALI ARAGÓ CALYPSO HILLS 42 CIALDI FELIBRES HILLS 42 TIBERINO ETRUSCHI LA RENAIXENÇA HILLS ALBANO MONTURIOL S.FELIÙ SMS DAUNO VERCELLI SALVÁ BRUTUS SPARTACUS CASSINIS EBRO BARONIE-K MARUSSI SECCHI-ADRIANO FARFALLE ALBATROS-CICERONE CRESQUES BERTRAN SELLI VENUS MORROT DE LA CIUTADELLA GORTANI SELE MONTE DELLA RONDINE TACITO SÓLLER ALABE DE MARCHI SIRENE SARDINIA D’ANCONA FLAVIO GIOIA AMENDOLARA 40 SALLUSTIO 40 MAGNAGHI POSEIDONE ROSSANO APHRODITI VAVILOV TIBULLO DIAMANTE MORROT CORNAGLIA V.EMANUELE CARIATI DE SA DRAGONERA MAJOR ISSEL PALINURO-STRABO OVIDIO VILADESTERS CATULLO GLAVKI ORAZIO MARSILI-PLINIO GLABRO ENOTRIO MANSEL JOHNSTON STONY SPONGE QUIRRA ENEA TITO LIVIO VIRGILIO ALCIONE AUGUSTO SES OLIVES GARIBALDI-GLAUCO LAMETINO 1 BROUKER JAUME 1 CORNACYA LAMETINO 2 COLOM TRAIANO LUCREZIO STOKES XABIA-IBIZA VESPASIANO LITERI SINAYA VALLSECA SISIFO EMILE BAUDOT GIULIO CESARE-CAESAR DREPANO ENARETE CASONI FONTSERÈ ICHNUSA IRA NAVTILOS CABO DE LA NAO AUSIÀS MARCH ANCHISE BELL GUYOT POMPEO PROMETEO MARTORELL ACESTE-TIBERIO EOLO FORMENTERA SOLUNTO ALKYONI FERRER SCUSO SAN VITO LOS MARTINES ALÍ BEI FINALE DON JUAN RESGUI RIBA SENTINELLE (SKERKI) BALIKÇI EL38 PLANAZO BIDDLECOMBE SILVIA 38 PLIS PLAS KEITH SECO DE PALOS ESTAFETTE HECATE ADVENTURE TALBOT TETIDE 170 km ÁGUILAS GALATEA PANTELLERIA ANFITRITE EMPEDOCLE PINNE ANTEO 2 KHAYR-AL-DIN CIMOTOE ANTEO 3 ABUBACER FOERSTNER NAMELESS PNT. E MADREPORE ANTEO 1 AVENZOAR PNT. CB CHELLA CABO DE GATA ANGELINA ALFEO SABINAR PNT. SW AVEMPACE-ALGARROBO MAIMONIDES RIDGE BANNOCK KOLUMBO DJIBOUTI-HERRADURA POLLUX BILIM ADRA-AVERROES MAIMONIDES BIRSA PNT. SE HERRADURA-DJIBOUTI LINOSA III AL-MANSOUR A EL SEGOVIANO DJIBOUTI VILLE ALBORÁN LINOSA I LINOSA II HÉSPERIDES HÉRCULES EL IDRISSI YUSUF KARPAS CATIFAS-W. -

POLÍTICA DE DIVERSIDADE E INCLUSÃO Sumário

POLÍTICA DE DIVERSIDADE E INCLUSÃO Sumário 5 Diversidade para combater as desigualdades 9 O Comitê de Diversidade e Inclusão 11 Entendendo um pouco sobre preconceito, discriminação, opressão estrutural, diversidade e inclusão 23 Quais temas serão tratados na Política de Diversidade e Inclusão da Fundação Tide Setubal? 39 Fundação Tide Setubal: princípios e compromissos 49 Canais de acolhimento 51 Referências Dezembro, 2020 Diversidade para combater as 1 desigualdades A Fundação Tide Setubal tem como missão “fomentar iniciativas que promovam a justiça social e o desenvol- vimento sustentável de periferias urbanas e contribuam para o enfrentamento das desigualdades socioespaciais das grandes cidades, em articulação com diversos agen- tes da sociedade civil, de instituições de pesquisa, do Estado e do mercado”. O uso do termo desigualdades, no plural, implica reconhecer que a vida dos sujeitos é atravessada não apenas pelas diferenças econômicas, mas também por uma série de fatores estruturais carac- terísticos de nossa sociedade que impactam a capacida- de das pessoas de viver e exercer seus direitos de forma plena. A discriminação e o preconceito sofridos por gru- pos minorizados também são vetores de exclusão social e contribuem para a reprodução e o aprofundamento do abismo social que separa incluídos e excluídos no Brasil. POLÍTICA DE DIVERSIDADE E INCLUSÃO 6 É com base nesse compromisso de combater as de- sigualdades em todas as suas formas que a Fundação apresenta esta Política de Diversidade e Inclusão. Nela, ficam estabelecidas as regras e compromissos que de- vem pautar a atuação de nossas colaboradoras e cola- boradores no sentido de combater ativamente todas as formas de discriminação e preconceito e promover a inclusão de todas as pessoas, independentemente de raça, gênero, orientação sexual, identidade de gênero, capacidade e origem nacional ou territorial. -

Ocean-Climate.Org

ocean-climate.org THE INTERACTIONS BETWEEN OCEAN AND CLIMATE 8 fact sheets WITH THE HELP OF: Authors: Corinne Bussi-Copin, Xavier Capet, Bertrand Delorme, Didier Gascuel, Clara Grillet, Michel Hignette, Hélène Lecornu, Nadine Le Bris and Fabrice Messal Coordination: Nicole Aussedat, Xavier Bougeard, Corinne Bussi-Copin, Louise Ras and Julien Voyé Infographics: Xavier Bougeard and Elsa Godet Graphic design: Elsa Godet CITATION OCEAN AND CLIMATE, 2016 – Fact sheets, Second Edition. First tome here: www.ocean-climate.org With the support of: ocean-climate.org HOW DOES THE OCEAN WORK? OCEAN CIRCULATION..............................………….....………................................……………….P.4 THE OCEAN, AN INDICATOR OF CLIMATE CHANGE...............................................…………….P.6 SEA LEVEL: 300 YEARS OF OBSERVATION.....................……….................................…………….P.8 The definition of words starred with an asterisk can be found in the OCP little dictionnary section, on the last page of this document. 3 ocean-climate.org (1/2) OCEAN CIRCULATION Ocean circulation is a key regulator of climate by storing and transporting heat, carbon, nutrients and freshwater all around the world . Complex and diverse mechanisms interact with one another to produce this circulation and define its properties. Ocean circulation can be conceptually divided into two Oceanic circulation is very sensitive to the global freshwater main components: a fast and energetic wind-driven flux. This flux can be described as the difference between surface circulation, and a slow and large density-driven [Evaporation + Sea Ice Formation], which enhances circulation which dominates the deep sea. salinity, and [Precipitation + Runoff + Ice melt], which decreases salinity. Global warming will undoubtedly lead Wind-driven circulation is by far the most dynamic. to more ice melting in the poles and thus larger additions Blowing wind produces currents at the surface of the of freshwaters in the ocean at high latitudes. -

Impacts of Climate Change on the Occurrence of Harmful Algal Blooms

Office of Water EPA 820-S-13-001 MC 4304T May 2013 Impacts of Climate Change on the Occurrence of Harmful Algal Blooms Summary Background Climate change is predicted to change many Algae occur naturally in marine and fresh waters. environmental conditions that could affect the Under favorable conditions that include adequate natural properties of fresh and marine waters both in light availability, warm waters, and high nutrient the US and worldwide. Changes in these factors levels, algae can rapidly grow and multiply causing could favor the growth of harmful algal blooms and “blooms.” Blooms of algae can cause damage to habitat changes such that marine HABs can invade aquatic environments by blocking sunlight and and occur in freshwater. An increase in the depleting oxygen required by other aquatic occurrence and intensity of harmful algal blooms organisms, restricting their growth and survival. may negatively impact the environment, human Some species of algae, including golden and red health, and the economy for communities across the algae and certain types of cyanobacteria, can produce US and around the world. The purpose of this fact potent toxins that can cause adverse health effects to sheet is to provide climate change researchers and wildlife and humans, such as damage to the liver and decision–makers a summary of the potential impacts nervous system. When algal blooms impair aquatic of climate change on harmful algal blooms in ecosystems or have the potential to affect human freshwater and marine ecosystems. Although much health, they are known as harmful algal blooms of the evidence presented in this fact sheet suggests (HABs). -

Subsurface Dinoflagellate Populations, Frontal Blooms and the Formation of Red Tide in the Southern Benguela Upwelling System

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 172: 253-264. 1998 Published October 22 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Subsurface dinoflagellate populations, frontal blooms and the formation of red tide in the southern Benguela upwelling system G. C. Pitcher*,A. J. Boyd, D. A. Horstman, B. A. Mitchell-Innes Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Private Bag X2, Rogge Bay 8012, Cape Town. South Africa ABSTRACT- The West Coast of South Africa is often subjected to problems associated with red tides which are usually attributed to blooms of migratory dinoflagellates. This study investigates the cou- pling between the physical environment and the biological behaviour and physiological adaptation of dinoflagellates in an attempt to understand bloom development, maintenance and decline. Widespread and persistent subsurface dinoflagellate populations domlnate the stratified waters of the southern Benguela during the latter part of the upwelling season. Chlorophyll concentrations as high as 50 mg m-3 are associated with the the]-mocline at approximately 20 m depth but photosynthesis in this region is restricted by low light. The subsurface population is brought to the surface in the region of the upwelling front. Here increased light levels are responsible for enhanced production, in some instances exceeding 80 mgC rn.' h ', and resulting in dense dinoflagellate concentrations in and around the uplifted thermocline. Under particular wind and current conditions these frontal bloon~sare trans- ported and accumulated inshore and red tides are formed. KEY WORDS: Dinoflagellates Subsurface populations . Frontal bloolns Red tide - Upwelling systems INTRODUCTION Pitcher 1996), or from physical damage, such as the clogging of fish gills (Grindley & Nel 1968, Brown et al. -

Ocean Circulation and Climate: an Overview

ocean-climate.org Bertrand Delorme Ocean Circulation and Yassir Eddebbar and Climate: an Overview Ocean circulation plays a central role in regulating climate and supporting marine life by transporting heat, carbon, oxygen, and nutrients throughout the world’s ocean. As human-emitted greenhouse gases continue to accumulate in the atmosphere, the Meridional Overturning Circulation (MOC) plays an increasingly important role in sequestering anthropogenic heat and carbon into the deep ocean, thus modulating the course of climate change. Anthropogenic warming, in turn, can influence global ocean circulation through enhancing ocean stratification by warming and freshening the high latitude upper oceans, rendering it an integral part in understanding and predicting climate over the 21st century. The interactions between the MOC and climate are poorly understood and underscore the need for enhanced observations, improved process understanding, and proper model representation of ocean circulation on several spatial and temporal scales. The ocean is in perpetual motion. Through its DRIVING MECHANISMS transport of heat, carbon, plankton, nutrients, and oxygen around the world, ocean circulation regulates Global ocean circulation can be divided into global climate and maintains primary productivity and two major components: i) the fast, wind-driven, marine ecosystems, with widespread implications upper ocean circulation, and ii) the slow, deep for global fisheries, tourism, and the shipping ocean circulation. These two components act industry. Surface and subsurface currents, upwelling, simultaneously to drive the MOC, the movement of downwelling, surface and internal waves, mixing, seawater across basins and depths. eddies, convection, and several other forms of motion act jointly to shape the observed circulation As the name suggests, the wind-driven circulation is of the world’s ocean. -

Crab Predators Are More Important at Higher Latitudes

Marine Biology (2019) 166:142 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00227-019-3587-0 ORIGINAL PAPER Variation in consumer pressure along 2500 km in a major upwelling system: crab predators are more important at higher latitudes Catalina A. Musrri1 · Alistair G. B. Poore2 · Iván A. Hinojosa3,4 · Erasmo C. Macaya4,5,6 · Aldo S. Pacheco7 · Alejandro Pérez‑Matus8 · Oscar Pino‑Olivares1 · Nicolás Riquelme‑Pérez1 · Wolfgang B. Stotz1 · Nelson Valdivia6,9 · Vieia Villalobos1,10 · Martin Thiel1,4,11 Received: 21 January 2019 / Accepted: 10 September 2019 © Springer-Verlag GmbH Germany, part of Springer Nature 2019 Abstract Consumer pressure in benthic communities is predicted to be higher at low than at high latitudes, but support for this pat- tern has been ambiguous, especially for herbivory. To understand large-scale variation in biotic interactions, we quantify consumption (predation and herbivory) along 2500 km of the Chilean coast (19°S–42°S). We deployed tethering assays at ten sites with three diferent baits: the crab Petrolisthes laevigatus as living prey for predators, dried squid as dead prey for predators/scavengers, and the kelp Lessonia spp. for herbivores. Underwater videos were used to characterize the consumer community and identify those species consuming baits. The species composition of consumers, frequency of occurrence, and maximum abundance (MaxN) of crustaceans and the blenniid fsh Scartichthys spp. varied across sites. Consumption of P. laevigatus and kelp did not vary with latitude, while squid baits were consumed more quickly at mid and high latitudes. This is likely explained by the increased occurrence of predatory crabs, which was positively correlated with consumption of squidpops after 2 h. -

Chapter 51. Biological Communities on Seamounts and Other Submarine Features Potentially Threatened by Disturbance

Chapter 51. Biological Communities on Seamounts and Other Submarine Features Potentially Threatened by Disturbance Contributors: J. Anthony Koslow, Peter Auster, Odd Aksel Bergstad, J. Murray Roberts, Alex Rogers, Michael Vecchione, Peter Harris, Jake Rice, Patricio Bernal (Co-Lead members) 1. Physical, chemical, and ecological characteristics 1.1 Seamounts Seamounts are predominantly submerged volcanoes, mostly extinct, rising hundreds to thousands of metres above the surrounding seafloor. Some also arise through tectonic uplift. The conventional geological definition includes only features greater than 1000 m in height, with the term “knoll” often used to refer to features 100 – 1000 m in height (Yesson et al., 2011). However, seamounts and knolls do not appear to differ much ecologically, and human activity, such as fishing, focuses on both. We therefore include here all such features with heights > 100 m. Only 6.5 per cent of the deep seafloor has been mapped, so the global number of seamounts must be estimated, usually from a combination of satellite altimetry and multibeam data as well as extrapolation based on size-frequency relationships of seamounts for smaller features. Estimates have varied widely as a result of differences in methodologies as well as changes in the resolution of data. Yesson et al. (2011) identified 33,452 seamount and guyot features > 1000 m in height and 138,412 knolls (100 – 1000 m), whereas Harris et al. (2014) identified 10,234 seamount and guyot features, based on a stricter definition that restricted seamounts to conical forms. Estimates of total abundance range to >100,000 seamounts and to 25 million for features > 100 m in height (Smith 1991; Wessel et al., 2010).