The Wind and the Waves

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Turning the Tide on Trash: Great Lakes

Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Turning the Tide On Trash A LEARNING GUIDE ON MARINE DEBRIS Floating marine debris in Hawaii NOAA PIFSC CRED Educators, parents, students, and Unfortunately, the ocean is currently researchers can use Turning the Tide under considerable pressure. The on Trash as they explore the serious seeming vastness of the ocean has impacts that marine debris can have on prompted people to overestimate its wildlife, the environment, our well being, ability to safely absorb our wastes. For and our economy. too long, we have used these waters as a receptacle for our trash and other Covering nearly three-quarters of the wastes. Integrating the following lessons Earth, the ocean is an extraordinary and background chapters into your resource. The ocean supports fishing curriculum can help to teach students industries and coastal economies, that they can be an important part of the provides recreational opportunities, solution. Many of the lessons can also and serves as a nurturing home for a be modified for science fair projects and multitude of marine plants and wildlife. other learning extensions. C ON T EN T S 1 Acknowledgments & History of Turning the Tide on Trash 2 For Educators and Parents: How to Use This Learning Guide UNIT ONE 5 The Definition, Characteristics, and Sources of Marine Debris 17 Lesson One: Coming to Terms with Marine Debris 20 Lesson Two: Trash Traits 23 Lesson Three: A Degrading Experience 30 Lesson Four: Marine Debris – Data Mining 34 Lesson Five: Waste Inventory 38 Lesson -

Basic Concepts in Oceanography

Chapter 1 XA0101461 BASIC CONCEPTS IN OCEANOGRAPHY L.F. SMALL College of Oceanic and Atmospheric Sciences, Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, United States of America Abstract Basic concepts in oceanography include major wind patterns that drive ocean currents, and the effects that the earth's rotation, positions of land masses, and temperature and salinity have on oceanic circulation and hence global distribution of radioactivity. Special attention is given to coastal and near-coastal processes such as upwelling, tidal effects, and small-scale processes, as radionuclide distributions are currently most associated with coastal regions. 1.1. INTRODUCTION Introductory information on ocean currents, on ocean and coastal processes, and on major systems that drive the ocean currents are important to an understanding of the temporal and spatial distributions of radionuclides in the world ocean. 1.2. GLOBAL PROCESSES 1.2.1 Global Wind Patterns and Ocean Currents The wind systems that drive aerosols and atmospheric radioactivity around the globe eventually deposit a lot of those materials in the oceans or in rivers. The winds also are largely responsible for driving the surface circulation of the world ocean, and thus help redistribute materials over the ocean's surface. The major wind systems are the Trade Winds in equatorial latitudes, and the Westerly Wind Systems that drive circulation in the north and south temperate and sub-polar regions (Fig. 1). It is no surprise that major circulations of surface currents have basically the same patterns as the winds that drive them (Fig. 2). Note that the Trade Wind System drives an Equatorial Current-Countercurrent system, for example. -

Intracratonic Asthenosphere Upwelling and Lithosphere Rejuvenation

Earth and Planetary Science Letters 260 (2007) 482–494 www.elsevier.com/locate/epsl Intracratonic asthenosphere upwelling and lithosphere rejuvenation beneath the Hoggar swell (Algeria): Evidence from HIMU metasomatised lherzolite mantle xenoliths ⁎ L. Beccaluva a, , A. Azzouni-Sekkal b, A. Benhallou c, G. Bianchini a, R.M. Ellam d, M. Marzola a, F. Siena a, F.M. Stuart d a Dipartimento di Scienze della Terra, Università di Ferrara, Italy b Faculté des Sciences de la Terre, Géographie et Aménagement du Territoire, Université des Sciences et Technologie Houari Boumédienne, Alger, Algeria c CRAAG (Centre de Recherche en Astronomie, Astrophysique et Géophysique), Alger, Algeria d Isotope Geoscience Unit, Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre, East Kilbride, UK Received 7 March 2007; received in revised form 23 May 2007; accepted 24 May 2007 Available online 2 June 2007 Editor: R.W. Carlson Abstract The mantle xenoliths included in Quaternary alkaline volcanics from the Manzaz-district (Central Hoggar) are proto-granular, anhydrous spinel lherzolites. Major and trace element analyses on bulk rocks and constituent mineral phases show that the primary compositions are widely overprinted by metasomatic processes. Trace element modelling of the metasomatised clinopyroxenes allows the inference that the metasomatic agents that enriched the lithospheric mantle were highly alkaline carbonate-rich melts such as nephelinites/melilitites (or as extreme silico-carbonatites). These metasomatic agents were characterized by a clear HIMU Sr–Nd–Pb isotopic signature, whereas there is no evidence of EM1 components recorded by the Hoggar Oligocene tholeiitic basalts. This can be interpreted as being due to replacement of the older cratonic lithospheric mantle, from which tholeiites generated, by asthenospheric upwelling dominated by the presence of an HIMU signature. -

Global Ship Accidents and Ocean Swell-Related Sea States

Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discuss., doi:10.5194/nhess-2017-142, 2017 Manuscript under review for journal Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci. Discussion started: 26 April 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC-BY 3.0 License. Global ship accidents and ocean swell-related sea states Zhiwei Zhang1, 2, Xiao-Ming Li2, 3 1 College of Geography and Environment, Shandong Normal University, Jinan, China 2 Key Laboratory of Digital Earth Science, Institute of Remote Sensing and Digital Earth, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 5 Beijing, China 3 Hainan Key Laboratory of Earth Observation, Sanya, China Correspondence to: X.-M. Li (E-mail: [email protected]) Abstract. With the increased frequency of shipping activities, navigation safety has become a major concern, especially when economic losses, human casualties and environmental issues are considered. As a contributing factor, sea state conditions play 10 a significant role in shipping safety. However, the types of dangerous sea states that trigger serious shipping accidents are not well understood. To address this issue, we analyzed the sea state characteristics during ship accidents that occurred in poor weather or heavy seas based on a ten-year ship accident dataset. The sea state parameters, including the significant wave height, the mean wave period and the mean wave direction, obtained from numerical wave model data were analyzed for selected ship accidents. The results indicated that complex sea states with the co-occurrence of wind sea and swell conditions represent 15 threats to sailing vessels, especially when these conditions include close wave periods and oblique wave directions. 1 Introduction The shipping industry delivers 90% of all world trade (IMO, 2011). -

A Numerical Study of the Long- and Short-Term Temperature Variability and Thermal Circulation in the North Sea

JANUARY 2003 LUYTEN ET AL. 37 A Numerical Study of the Long- and Short-Term Temperature Variability and Thermal Circulation in the North Sea PATRICK J. LUYTEN Management Unit of the Mathematical Models, Brussels, Belgium JOHN E. JONES AND ROGER PROCTOR Proudman Oceanographic Laboratory, Bidston, United Kingdom (Manuscript received 3 January 2001, in ®nal form 4 April 2002) ABSTRACT A three-dimensional numerical study is presented of the seasonal, semimonthly, and tidal-inertial cycles of temperature and density-driven circulation within the North Sea. The simulations are conducted using realistic forcing data and are compared with the 1989 data of the North Sea Project. Sensitivity experiments are performed to test the physical and numerical impact of the heat ¯ux parameterizations, turbulence scheme, and advective transport. Parameterizations of the surface ¯uxes with the Monin±Obukhov similarity theory provide a relaxation mechanism and can partially explain the previously obtained overestimate of the depth mean temperatures in summer. Temperature strati®cation and thermocline depth are reasonably predicted using a variant of the Mellor±Yamada turbulence closure with limiting conditions for turbulence variables. The results question the common view to adopt a tuned background scheme for internal wave mixing. Two mechanisms are discussed that describe the feedback of the turbulence scheme on the surface forcing and the baroclinic circulation, generated at the tidal mixing fronts. First, an increased vertical mixing increases the depth mean temperature in summer through the surface heat ¯ux, with a restoring mechanism acting during autumn. Second, the magnitude and horizontal shear of the density ¯ow are reduced in response to a higher mixing rate. -

Prioritization of Oxygen Delivery During Elevated Metabolic States

Respiratory Physiology & Neurobiology 144 (2004) 215–224 Eat and run: prioritization of oxygen delivery during elevated metabolic states James W. Hicks∗, Albert F. Bennett Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697, USA Accepted 25 May 2004 Abstract The principal function of the cardiopulmonary system is the matching of oxygen and carbon dioxide transport to the metabolic V˙ requirements of different tissues. Increased oxygen demands ( O2 ), for example during physical activity, result in a rapid compensatory increase in cardiac output and redistribution of blood flow to the appropriate skeletal muscles. These cardiovascular changes are matched by suitable ventilatory increments. This matching of cardiopulmonary performance and metabolism during activity has been demonstrated in a number of different taxa, and is universal among vertebrates. In some animals, large V˙ increments in aerobic metabolism may also be associated with physiological states other than activity. In particular, O2 may increase following feeding due to the energy requiring processes associated with prey handling, digestion and ensuing protein V˙ V˙ synthesis. This large increase in O2 is termed “specific dynamic action” (SDA). In reptiles, the increase in O2 during SDA may be 3–40-fold above resting values, peaking 24–36 h following ingestion, and remaining elevated for up to 7 days. In addition to the increased metabolic demands, digestion is associated with secretion of H+ into the stomach, resulting in a large metabolic − alkalosis (alkaline tide) and a near doubling in plasma [HCO3 ]. During digestion then, the cardiopulmonary system must meet the simultaneous challenges of an elevated oxygen demand and a pronounced metabolic alkalosis. -

Mapping Current and Future Priorities

Mapping Current and Future Priorities for Coral Restoration and Adaptation Programs International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) Ad Hoc Committee on Reef Restoration 2019 Interim Report This report was prepared by James Cook University, funded by the Australian Institute for Marine Science on behalf of the ICRI Secretariat nations Australia, Indonesia and Monaco. Suggested Citation: McLeod IM, Newlands M, Hein M, Boström-Einarsson L, Banaszak A, Grimsditch G, Mohammed A, Mead D, Pioch S, Thornton H, Shaver E, Souter D, Staub F. (2019). Mapping Current and Future Priorities for Coral Restoration and Adaptation Programs: International Coral Reef Initiative Ad Hoc Committee on Reef Restoration 2019 Interim Report. 44 pages. Available at icriforum.org Acknowledgements The ICRI ad hoc committee on reef restoration are thanked and acknowledged for their support and collaboration throughout the process as are The International Coral Reef Initiative (ICRI) Secretariat, Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) and TropWATER, James Cook University. The committee held monthly meetings in the second half of 2019 to review the draft methodology for the analysis and subsequently to review the drafts of the report summarising the results. Professor Karen Hussey and several members of the ad hoc committee provided expert peer review. Research support was provided by Melusine Martin and Alysha Wincen. Advisory Committee (ICRI Ad hoc committee on reef restoration) Ahmed Mohamed (UN Environment), Anastazia Banaszak (International Coral Reef Society), -

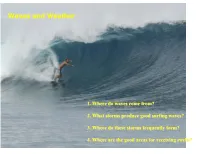

Waves and Weather

Waves and Weather 1. Where do waves come from? 2. What storms produce good surfing waves? 3. Where do these storms frequently form? 4. Where are the good areas for receiving swells? Where do waves come from? ==> Wind! Any two fluids (with different density) moving at different speeds can produce waves. In our case, air is one fluid and the water is the other. • Start with perfectly glassy conditions (no waves) and no wind. • As wind starts, will first get very small capillary waves (ripples). • Once ripples form, now wind can push against the surface and waves can grow faster. Within Wave Source Region: - all wavelengths and heights mixed together - looks like washing machine ("Victory at Sea") But this is what we want our surfing waves to look like: How do we get from this To this ???? DISPERSION !! In deep water, wave speed (celerity) c= gT/2π Long period waves travel faster. Short period waves travel slower Waves begin to separate as they move away from generation area ===> This is Dispersion How Big Will the Waves Get? Height and Period of waves depends primarily on: - Wind speed - Duration (how long the wind blows over the waves) - Fetch (distance that wind blows over the waves) "SMB" Tables How Big Will the Waves Get? Assume Duration = 24 hours Fetch Length = 500 miles Significant Significant Wind Speed Wave Height Wave Period 10 mph 2 ft 3.5 sec 20 mph 6 ft 5.5 sec 30 mph 12 ft 7.5 sec 40 mph 19 ft 10.0 sec 50 mph 27 ft 11.5 sec 60 mph 35 ft 13.0 sec Wave height will decay as waves move away from source region!!! Map of Mean Wind -

Sea State in Marine Safety Information Present State, Future Prospects

Sea State in Marine Safety Information Present State, future prospects Henri SAVINA – Jean-Michel LEFEVRE Météo-France Rogue Waves 2004, Brest 20-22 October 2004 JCOMM Joint WMO/IOC Commission for Oceanography and Marine Meteorology The future of Operational Oceanography Intergovernmental body of technical experts in the field of oceanography and marine meteorology, with a mandate to prepare both regulatory (what Member States shall do) and guidance (what Member States should do) material. TheThe visionvision ofof JCOMMJCOMM Integrated ocean observing system Integrated data management State-of-the-art technologies and capabilities New products and services User responsiveness and interaction Involvement of all maritime countries JCOMM structure Terms of Reference Expert Team on Maritime Safety Services • Monitor / review operations of marine broadcast systems, including GMDSS and others for vessels not covered by the SOLAS convention •Monitor / review technical and service quality standards for meteo and oceano MSI, particularly for the GMDSS, and provide assistance and support to Member States • Ensure feedback from users is obtained through appropriate channels and applied to improve the relevance, effectiveness and quality of services • Ensure effective coordination and cooperation with organizations, bodies and Member States on maritime safety issues • Propose actions as appropriate to meet requirements for international coordination of meteorological and related communication services • Provide advice to the SCG and other Groups of JCOMM on issues related to MSS Chair selected by Commission. OPEN membership, including representatives of the Issuing Services for GMDSS, of IMO, IHO, ICS, IMSO, and other user groups GMDSS Global Maritime Distress & Safety System Defined by IMO for the provision of MSI and the coordination of SAR alerts on a global basis. -

Arenicola Marina During Low Tide

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Published June 15 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Sulfide stress and tolerance in the lugworm Arenicola marina during low tide Susanne Volkel, Kerstin Hauschild, Manfred K. Grieshaber Institut fiir Zoologie, Lehrstuhl fur Tierphysiologie, Heinrich-Heine-Universitat, Universitatsstr. 1, D-40225 Dusseldorf, Germany ABSTRACT: In the present study environmental sulfide concentrations in the vicinity of and within burrows of the lugworm Arenicola marina during tidal exposure are presented. Sulfide concentrations in the pore water of the sediment ranged from 0.4 to 252 pM. During 4 h of tidal exposure no significant changes of pore water sulfide concentrations were observed. Up to 32 pM sulfide were measured in the water of lugworm burrows. During 4 h of low tide the percentage of burrows containing sulfide increased from 20 to 50% in July and from 36 to 77% in October A significant increase of median sulfide concentrations from 0 to 14.5 pM was observed after 5 h of emersion. Sulfide and thiosulfate concentrations in the coelomic fluid and succinate, alanopine and strombine levels in the body wall musculature of freshly caught A. marina were measured. During 4 h of tidal exposure in July the percentage of lugworms containing sulfide and maximal sulfide concentrations increased from 17 % and 5.4 pM to 62% and 150 pM, respectively. A significant increase of median sulfide concentrations was observed after 2 and 3 h of emersion. In October, changes of sulfide concentrations were less pronounced. Median thiosulfate concentrations were 18 to 32 FM in July and 7 to 12 ~.IMin October No significant changes were observed during tidal exposure. -

Headland Sediment Bypassing Processes

UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS HEADLAND SEDIMENT BYPASSING PROCESSES Doutoramento em Geologia Especialidade em Geodinâmica Externa Mónica Sofia Afonso Ribeiro Tese orientada por: Professor Doutor Rui Pires de Matos Taborda Doutora Aurora da Conceição Coutinho Rodrigues Bizarro Documento especialmente elaborado para a obtenção do grau de doutor 2017 UNIVERSIDADE DE LISBOA FACULDADE DE CIÊNCIAS HEADLAND SEDIMENT BYPASSING PROCESSES Doutoramento em Geologia Especialidade em Geodinâmica Externa Mónica Sofia Afonso Ribeiro Tese orientada por: Professor Doutor Rui Pires de Matos Taborda Doutora Aurora da Conceição Coutinho Rodrigues Bizarro Júri: Presidente: ● Doutora Maria da Conceição Pombo de Freitas Vogais: ● Doutor António Henrique da Fontoura Klein ● Doutor Óscar Manuel Fernandes Cerveira Ferreira ● Doutora Anabela Tavares Campos Oliveira ● Doutor César Augusto Canelhas Freire de Andrade ● Doutor Rui Pires de Matos Taborda Documento especialmente elaborado para a obtenção do grau de doutor Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, no âmbito da Bolsa de Doutoramento com a referência SFRH/BD/79126/2011 2017 Em memória do meu irmão Luís Acknowledgments | Agradecimentos O doutoramento é um processo exigente, por vezes solitário, mas que só é possível com o apoio e a colaboração de outras pessoas e instituições. Portanto, resta-me agradecer a todos os que contribuíram para a conclusão deste trabalho. Em primeiro lugar agradeço aos meus orientadores, Rui Taborda e Aurora Bizarro, que têm acompanhado o meu trabalho desde os meus primeiros passos na Geologia Marinha, já lá vão 10 anos! A eles agradeço o incentivo para iniciar este projeto, o apoio demonstrado em todas as fases do trabalho, a confiança e a amizade. Ao Rui agradeço, em particular, a partilha e discussão de ideias e os desafios constantes que me permitiram evoluir. -

Marine Forecasting at TAFB [email protected]

Marine Forecasting at TAFB [email protected] 1 Waves 101 Concepts and basic equations 2 Have an overall understanding of the wave forecasting challenge • Wave growth • Wave spectra • Swell propagation • Swell decay • Deep water waves • Shallow water waves 3 Wave Concepts • Waves form by the stress induced on the ocean surface by physical wind contact with water • Begin with capillary waves with gradual growth dependent on conditions • Wave decay process begins immediately as waves exit wind generation area…a.k.a. “fetch” area 4 5 Wave Growth There are three basic components to wave growth: • Wind speed • Fetch length • Duration Wave growth is limited by either fetch length or duration 6 Fully Developed Sea • When wave growth has reached a maximum height for a given wind speed, fetch and duration of wind. • A sea for which the input of energy to the waves from the local wind is in balance with the transfer of energy among the different wave components, and with the dissipation of energy by wave breaking - AMS. 7 Fetches 8 Dynamic Fetch 9 Wave Growth Nomogram 10 Calculate Wave H and T • What can we determine for wave characteristics from the following scenario? • 40 kt wind blows for 24 hours across a 150 nm fetch area? • Using the wave nomogram – start on left vertical axis at 40 kt • Move forward in time to the right until you reach either 24 hours or 150 nm of fetch • What is limiting factor? Fetch length or time? • Nomogram yields 18.7 ft @ 9.6 sec 11 Wave Growth Nomogram 12 Wave Dimensions • C=Wave Celerity • L=Wave Length •