Methodological Study on the Evaluation of Face Mask Use Scale Among Public Adult: Cross-Language and Psychometric Testing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LC Paper No. CB(2)2279/11-12(03)

LC Paper No. CB(2)2279/11-12(03) For discussion on 11 June 2012 Legislative Council Panel on Health Services Redevelopment of Kwong Wah Hospital Purpose This paper briefs Members on the proposed redevelopment of Kwong Wah Hospital (KWH). Background 2. At present, the Hospital Authority (HA) provides public hospital services for Sham Shui Po, Mongkok, Wong Tai Sin, Kwai Tsing, Tsuen Wan and North Lantau districts through its Kowloon West (KW) cluster, which comprises KWH, Caritas Medical Centre, Our Lady of Maryknoll Hospital, Wong Tai Sin Hospital, Kwai Chung Hospital, Princess Margaret Hospital and Yan Chai Hospital. KWH was established in 1911 and is a major acute hospital offering a comprehensive range of acute care services. Need for Redevelopment of KWH Aging Hospital Buildings 3. The majority of the KWH buildings is over 50 years old. With the passage of time, its space provision has become inadequate and building services installations out-dated. The structural conditions of the buildings have also been deteriorating. Being located in a densely populated area, KWH is one of the busiest hospitals of HA. The extremely heavy utilisation of KWH has also accelerated deterioration of its facilities. 4. Apart from the Tung Wah Group of Hospitals (TWGHs) Tsui Tsin Tong Out-patient Building (TTT OPB) which was built in 1999 and the Tung Wah Museum which is a declared monument built in 1911, the rest of the hospital buildings at KWH are old and in need of redevelopment. The Main Hospital Building was constructed in stages between 1959 and 1964. The Staff Barracks, Chinese Medicine Clinical Research and Services Centre, Nurses’ Quarters and Administration Building were all constructed in the 1960s and are in need of constant repairs. -

HA Go Activation Location

HA Go Activation Location Region Hospital Counter G/F, Block A Grantham Hospital G/F, Kwok Tak Seng Heart Centre G/F, Lo Fong Shiu Po Eye Centre MacLehose Medical 2/F, Specialist Out-Patient Clinic Rehabilitation Centre Registration Office, Department of Clinical Oncology (Out-Patient Clinic), LG1/F, East Block Pamela Youde Nethersole J7, Psychiatric Out-Patient Department, 7/F, East Block Eastern Hospital Central Registration Centre, G/F, Specialist Out-Patient Block J2, Psychiatric Specialist Out-Patient Clinic J5, Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Day Centre 3/F, Block S 4/F, Block S Queen Mary Hospital 5/F, Block S Hong 6/F, Block S Kong 7/F, Block S Island 3/F, South Wing, David Trench Rehabilitation Centre Registration Counter, G/F, Specialist Out-Patient Ruttonjee Hospital Department The Duchess of Kent Children's Hospital at Specialist Out-Patient Clinic, G/F, A Block Sandy Bay Registration Counter, Specalist Out-Patient Clinic, G/F, Tung Wah Eastern Main Block Hospital Counter, Eye Clinic, G/F, TWGHs Lo Ka Chow Memorial Ophthalmic Centre Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Fung Yiu King Geriatric Day Hospital Hospital C5, Day Centre Tung Wah Hospital H3, Specialist Out-Patient Clinic L4, Eye, Nose & Throat Centre Tsan Yuk Hospital G/F, The Specialist Outpatient Clinic (Obstetrics) 1 / 4 HA Go Activation Location Region Hospital Counter Room 37, Ophthalmic Centre, 2/F, Wai Ming Block Caritas Medical Centre Specialist Out-Patient Clinic, 3/F, Wai Ming Block Reception Office, 4/F, Wai Ming Block Hong Kong Buddhist Enquiry counter, Out-Patient -

Hospital Authority Special Visiting Arrangement in Hospitals/Units with Non-Acute Settings Under Emergency Response Level Notes to Visitors

Hospital Authority Special Visiting Arrangement in Hospitals/Units with Non-acute Settings under Emergency Response Level Notes to Visitors 1. Hospital Authority implemented special visiting arrangement in four phases on 21 April 2021, 29 May 2021, 25 June 2021 and 23 July 2021 respectively (as appended table). Cluster Hospitals/Units with non-acute settings Cheshire Home, Chung Hom Kok Ruttonjee Hospital Hong Kong East Mixed Infirmary and Convalescent Wards Cluster Tung Wah Eastern Hospital Wong Chuk Hang Hospital Grantham Hospital MacLehose Medical Rehabilitation Centre Hong Kong West The Duchess of Kent Children’s Hospital at Sandy Bay Cluster Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Fung Yiu King Hospital Tung Wah Hospital Kowloon East Haven of Hope Hospital Cluster Hong Kong Buddhist Hospital Kowloon Central Kowloon Hospital (Except Psychiatric Wards) Cluster Our Lady of Maryknoll Hospital Tung Wah Group of Hospitals Wong Tai Sin Hospital Caritas Medical Centre Developmental Disabilities Unit, Wai Yee Block Medical and Geriatrics/Orthopaedics Rehabilitation Wards and Palliative Care Ward, Wai Ming Block North Lantau Hospital Kowloon West Extended Care Wards Cluster Princess Margaret Hospital Lai King Building Yan Chai Hospital Orthopaedics and Traumatology Rehabilitation Ward and Medical Extended Care Unit (Rehabilitation and Infirmary Wards), Multi-services Complex New Territories Bradbury Hospice East Cluster Cheshire Home, Shatin North District Hospital 4B Convalescent Rehabilitation Ward Shatin Hospital (Except Psychiatric Wards) Tai Po Hospital (Except Psychiatric Wards) Pok Oi Hospital Tin Ka Ping Infirmary New Territories Siu Lam Hospital West Cluster Tuen Mun Hospital Rehabilitation Block (Except Day Wards) H1 Palliative Ward 2. Hospital staff will contact patients’ family members for explanation of special visiting arrangement and scheduling the visits. -

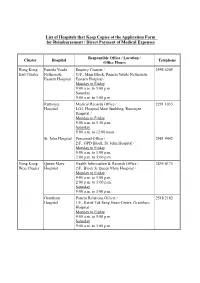

List of Hospitals That Keep Copies of the Application Form for Reimbursement / Direct Payment of Medical Expenses

List of Hospitals that Keep Copies of the Application Form for Reimbursement / Direct Payment of Medical Expenses Responsible Office / Location / Cluster Hospital Telephone Office Hours Hong Kong Pamela Youde Enquiry Counter / 2595 6205 East Cluster Nethersole G/F., Main Block, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital Eastern Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Ruttonjee Medical Records Office / 2291 1035 Hospital LG1, Hospital Main Building, Ruttonjee Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 12:00 noon St. John Hospital Personnel Office / 2981 9442 2/F., OPD Block, St. John Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. 2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. Hong Kong Queen Mary Health Information & Records Office / 2855 4175 West Cluster Hospital 2/F., Block S, Queen Mary Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. 2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Grantham Patient Relations Officer / 2518 2182 Hospital 1/F., Kwok Tak Seng Heart Centre, Grantham Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. - 2 - Responsible Office / Location / Cluster Hospital Telephone Office Hours Kowloon Kwong Wah Medical Report Office / 3517 5216 West Cluster Hospital 1/F., Central Stack, Kwong Wah Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. -

Hospital Authority List of Medical Social Services Units (January 2019)

Hospital Authority List of Medical Social Services Units (January 2019) Name of Hospital Address Tel No. Fax No. 1. Alice Ho Miu Ling Nethersole 11 Chuen On Road, Tai Po, N.T. 2689 2020 2662 3152 Hospital (Non- psychiatric medical social service) 2. Bradbury Hospital 17 A Kung Kok Shan Road, 2645 8832 2762 1518 Shatin, N.T. 3. Caritas Medical Centre 111 Wing Hong Street, 3408 7709 2785 3192 Shamshuipo, Kowloon 4. Cheshire Home 128 Chung Hom Kok Road, 2899 1391 2813 8752 (Chung Hom Kok) Hong Kong 5. Cheshire Home (Shatin) 30 A Kung Kok Shan Road, 2636 7269 2636 7242 Shatin, N.T. 6. TWGHs Fung Yiu King Hospital 9 Sandy Bay Road, Hong Kong 2855 6236 2904 9021 7. Grantham Hospital 125 Wong Chuk Hang Road, 2518 2678 2580 7629 Aberdeen, Hong Kong 8. Haven of Hope Hospital 8 Haven of Hope Road, 2703 8227 2703 8230 Tseung Kwan O, Kowloon 9. Hong Kong Buddhist Hospital 10 Heng Lam Road, Lok Fu, 2339 6253 2339 6298 Kowloon 10. Kowloon Hospital Mezzanine Floor, Kowloon 3129 7806/ 3129 7838 (Ward 2B at Rehabilitation Hospital Rehabilitation Building, 3129 7831 Building ) 147A, Argyle Street, Kowloon 11. Kwong Wah Hospital 25 Waterloo Road, Kowloon 3517 2900 3517 2959 12. MacLehose Medical 7 Sha Wan Drive, 2872 7131 2872 7909 Rehabilitation Centre Pokfulam, Hong Kong Name of Hospital Address Tel No. Fax No. 13. Our Lady of Maryknoll Hospital 118 Shatin Pass Road, 2354 2285 2324 8719 Wong Tai Sin, Kowloon 14. Pok Oi Hospital Au Tau, Yuen Long, N.T. 2486 8140 2486 8095 2486 8141 15. -

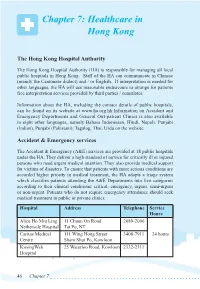

Chapter 7: Healthcare in Hong Kong

Chapter 7: Healthcare in Hong Kong The Hong Kong Hospital Authority The Hong Kong Hospital Authority (HA) is responsible for managing all local public hospitals in Hong Kong. Staff of the HA can communicate in Chinese (mainly the Cantonese dialect) and / or English. If interpretation is needed for other languages, the HA will use reasonable endeavours to arrange for patients free interpretation services provided by third parties / consulates. Information about the HA, including the contact details of public hospitals, can be found on its website at www.ha.org.hk.Information on Accident and Emergency Departments and General Out-patient Clinics is also available in eight other languages, namely Bahasa Indonesian, Hindi, Nepali, Punjabi (Indian), Punjabi (Pakistani), Tagalog, Thai, Urdu on the website. Accident & Emergency services The Accident & Emergency (A&E) services are provided at 18 public hospitals under the HA. They deliver a high standard of service for critically ill or injured persons who need urgent medical attention. They also provide medical support for victims of disasters. To ensure that patients with more serious conditions are accorded higher priority in medical treatment, the HA adopts a triage system which classifies patients attending the A&E Departments into five categories according to their clinical conditions: critical, emergency, urgent, semi-urgent or non-urgent. Patients who do not require emergency attendance should seek medical treatment in public or private clinics. Hospital Address Telephone Service Hours Alice Ho Miu Ling 11 Chuen On Road 2689-2000 Nethersole Hospital Tai Po, NT Caritas Medical 111 Wing Hong Street 3408-7911 24 hours Centre Sham Shui Po, Kowloon KwongWah 25 Waterloo Road, Kowloon 2332-2311 Hospital 46 Chapter 7 North District 9 Po Kin Road 2683-8888 Hospital Sheung Shui, NT North Lantau 1/F, 8 Chung Yan Road 3467-7000 Hospital Tung Chung, Lantau, N.T. -

List of Medical Social Services Units Under Social Welfare Department

List of Medical Social Services Units Under Social Welfare Department Hong Kong Name of Hospital/Clinic Tel. No. Email Address 1. Queen Mary Hospital 2255 3762 [email protected] 2255 3764 2. Wong Chuk Hang Hospital 2873 7201 [email protected] 3. Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern 2595 6262 [email protected] Hospital 4. Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern 2595 6773 [email protected] Hospital (Psychiatric Department) Kowloon Name of Hospital/Clinic Tel. No. Email Address 5. Tseung Kwan O Hospital 2208 0335 [email protected] 2208 0327 6. United Christian Hospital 3949 5178 [email protected] (Psychiatry) 7. Queen Elizabeth Hospital 3506 7021 [email protected] 3506 7027 3506 5499 3506 4021 8. Hong Kong Eye Hospital 2762 3069 [email protected] 9. Kowloon Hospital Rehabilitation 3129 7857 [email protected] Building 10. Kowloon Hospital 3129 6193 [email protected] 11. Kowloon Hospital 2768 8534 [email protected] (Psychiatric Department) 1 The New Territories Name of Hospital/Clinic Tel. No. Email Address 12. Prince of Wales Hospital 3505 2400 [email protected] 13. Shatin Hospital 3919 7521 [email protected] 14. Tai Po Hospital 2607 6304 [email protected] Sub-office Tai Po Hospital (Child and Adolescent 2689 2486 [email protected] Mental Health Centre) 15. North District Hospital 2683 7750 [email protected] 16. Tin Shui Wai Hospital 3513 5391 [email protected] 17. Castle Peak Hospital 2456 7401 [email protected] 18. Siu Lam Hospital 2456 7186 [email protected] 19. -

Hospital Authority's Planned Projects for 2021-2022

LC Paper No. CB(4)503/20-21(02) Head 708 Subhead 8083MM One-Off Grant to the Hospital Authority for Minor Works Projects 2021-22 Planned Projects Prepared by the Hospital Authority February 2021 Head 708 : Subhead 8083MM One-off Grant to the Hospital Authority for Minor Works Projects for the 2019-20 Financial Year Part A - Previously approved items and other items to commence in 2020-21 with expected expenditure in 2020-21 and/or 2021-22 Actual Approved Cumulative Revised Estimated cash flow in subsequent years Expenditure Estimate Priority / Project Expenditure Estimate Project Title (1.4.2020 to 2021-22 Post Item No. Estimate to 31.3.2020 2020-21 31.10.2020) 2022-23 2023-24 2024-25 2024-25 ($'000) (I) Previously approved items (up to 31.10.2020) with expected expenditure in 2020-21 and/or 2021-22 EMR15-604 Modernisation of lifts in Day Treatment Block and Special Block in Prince of Wales Hospital 16,794 16,540 254 254 - - - - - EMR16-104 Replacement of the local central control and monitoring system for Wong Chuk Hang Hospital 1,280 1,150 39 101 - 30 - - - EMR16-401 Replacement of fire alarm and detection system at Hospital Main Block in Tseung Kwan O 6,500 6,500 (1,371) (1,371) - - - - - Hospital EMR16-504 Replacement of 1 no. main switch board for Block A in Yan Chai Hospital 2,345 2,202 142 142 - - - - - EMR16-505 Replacement of building management system at Multi Services Complex in Yan Chai Hospital 3,500 3,148 55 55 297 - - - - EMR16-506 Replacement of the air handling unit for Department of Central Supporting Services at 1/F, 502 526 (24) (24) - - - - - Block B in Yan Chai Hospital EMR17-102 Replacement of emergency generators for Hospital Block at St. -

Yan Chai Hospital

Decommissioning and Disposal Of Incinerator at Yan Chai Hospital Project Profile July 2009 Submitted by: The Hospital Authority, Hong Kong Decommissioning and Disposal of Yan Chai Hospital Incinerators Decommissioning and Disposal of Yan Chai Hospital Incinerators Project PROJECT PROFILE Document Reference: 2525007A Prepared by Parsons Brinckerhoff For internal use only: Fleur Parkinson 28 July Jonathan 1 Issued and Michael Jonathan Roe 09 Roe Chu Fleur Parkinson 13 July Jonathan 0 Draft to Client and Michael Jonathan Roe 2009 Roe Chu Rev Date Purpose/Description Prepared by Checked by Approved by 2525007A i July 2009 Decommissioning and Disposal of Yan Chai Hospital Incinerators CONTENTS 1. BASIC INFORMATION......................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Project Title.............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Purpose and Nature of the Project............................................................................ 1 1.3 Name of Project Proponent ...................................................................................... 1 1.4 Location and Scale of Project................................................................................... 1 1.5 Number of Designated Project to be Covered by this Project Profile......................... 2 1.6 Name and Telephone Number of Contact Persons................................................... 2 2. OUTLINE OF PLANNING AND IMPLEMENTATION PROGRAMME -

Reimbursement Forms in Designated Site

List of Hospitals that Keep Copies of Application FORM A and Application FORM B Responsible Office / Location / Cluster Hospital Telephone Office Hours Hong Kong Pamela Youde Enquiry Counter / 2595 6205 East Cluster Nethersole G/F., Main Block, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital Eastern Hospital / Monday to Friday 8:30 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Ruttonjee & Tang Medical Records Office / 2291 1035 Shiu Kin LG1, Hospital Main Building, Ruttonjee Hospitals Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. 2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. St. John Hospital Medical Records Office / Human Resources 2986 2246 Department/ 2/F., Out-Patients Block, St. John Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. 2:00 p.m. to 5:30 p.m. Hong Kong Queen Mary Health Information & Records Office / 2255 4175 West Cluster Hospital 2/F., Block S, Queen Mary Hospital / (Monday to Monday to Friday Friday) 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. 2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. Saturday 2255 3660 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. (Saturday) Grantham Health Information & Records Office / 2518 2201 Hospital G/F., Main Block, Grantham Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. - 2 - Responsible Office / Location / Cluster Hospital Telephone Office Hours Kowloon Kwong Wah Medical Report Office / 3517 5216 West Cluster Hospital 12/F., Central Stack, Kwong Wah Hospital / Monday to Friday 8:45 a.m. -

Reimbursement Forms in Designated Site

List of Hospitals that Keep Copies of Application FORM A and Application FORM B Responsible Office / Location / Cluster Hospital Telephone Office Hours Hong Kong Pamela Youde Enquiry Counter / 2595 6205 East Cluster Nethersole G/F., Main Block, Pamela Youde Nethersole Eastern Hospital Eastern Hospital / Monday to Friday 8:30 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. Ruttonjee & Tang Medical Records Office / 2291 1035 Shiu Kin LG1, Hospital Main Building, Ruttonjee Hospitals Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. 2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. St. John Hospital Medical Records Office / Human Resources 2986 2246 Department/ 2/F., Out-Patients Block, St. John Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. 2:00 p.m. to 5:30 p.m. Hong Kong Queen Mary Health Information & Records Office / 2255 4175 West Cluster Hospital 2/F., Block S, Queen Mary Hospital / (Monday to Monday to Friday Friday) 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. 2:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. Saturday 2255 3660 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. (Saturday) Grantham Health Information & Records Office / 2518 2201 Hospital G/F., Main Block, Grantham Hospital / Monday to Friday 9:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. Saturday 9:00 a.m. to 1:00 p.m. - 2 - Responsible Office / Location / Cluster Hospital Telephone Office Hours Kowloon Kwong Wah Medical Report Office / 3517 5216 West Cluster Hospital 12/F., Central Stack, Kwong Wah Hospital / Monday to Friday 8:45 a.m. -

Utilisation of Accident and Emergency Services by Patients Who Could Be Managed by General Practitioners

HEALTH SERVICES RESEARCH FUND – HEALTH CARE AND PROMOTION FUND Utilisation of accident and emergency services by patients who could be managed by general practitioners Introduction Key Messages 1. The reasons for high utilisation rates The accident and emergency (A&E) department is intended for patients with of accident and emergency (A&E) life-threatening or critical conditions that need immediate hospital services. department services are complex Nonetheless, A&E departments are becoming popular venues for primary care. and reflect problems of service This rise in inappropriate A&E attendance is considered a serious threat to the delivery by general practitioners health care system because it utilises resources needed to provide true emergency (GPs). 2. A network of GPs providing out- cases with quality care. Some studies have found that up to two thirds of of-hours services would reduce the patients who attend the A&E department have problems that could be managed unnecessary use of A&E services. appropriately by general practitioners (GPs). 3. Better interfacing between primary and secondary care and between the Traditionally, studies of emergency department visits have relied on surveys public and private sectors would facilitate patients being referred of patients at one or two hospitals to determine who used these facilities and back to and effectively cared for by why. A comprehensive picture of A&E patients from the whole community was GPs. not easily obtained because only a limited number of hospitals were sampled. Moreover, data were usually collected during the day and seldom across midnight. Hong Kong Med J 2007;13(Suppl 4):S28-31 Time is considered an important variable when determining morbidity patterns and reasons for utilisation.