Annual Report of Unido 1998

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lessons from Burkina Faso's Thomas Sankara By

Pan-Africanism and African Renaissance in Contemporary Africa: Lessons from Burkina Faso’s Thomas Sankara By: Moorosi Leshoele (45775389) Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy At the UNIVERSITY OF SOUTH AFRICA SUPERVISOR: Prof Vusi Gumede (September 2019) DECLARATION (Signed) i | P a g e DEDICATION I dedicate this thesis to Thomas Noel Isadore Sankara himself, one of the most underrated leaders in Africa and the world at large, who undoubtedly stands shoulder to shoulder with ANY leader in the world, and tall amongst all of the highly revered and celebrated revolutionaries in modern history. I also dedicate this to Mariam Sankara, Thomas Sankara’s wife, for not giving up on the long and hard fight of ensuring that justice is served for Sankara’s death, and that those who were responsible, directly or indirectly, are brought to book. I also would like to tremendously thank and dedicate this thesis to Blandine Sankara and Valintin Sankara for affording me the time to talk to them at Sankara’s modest house in Ouagadougou, and for sharing those heart-warming and painful memories of Sankara with me. For that, I say, Merci boucop. Lastly, I dedicate this to my late father, ntate Pule Leshoele and my mother, Mme Malimpho Leshoele, for their enduring sacrifices for us, their children. ii | P a g e AKNOWLEDGEMENTS To begin with, my sincere gratitude goes to my Supervisor, Professor Vusi Gumede, for cunningly nudging me to enrol for doctoral studies at the time when the thought was not even in my radar. -

Africans: the HISTORY of a CONTINENT, Second Edition

P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 This page intentionally left blank ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 africans, second edition Inavast and all-embracing study of Africa, from the origins of mankind to the AIDS epidemic, John Iliffe refocuses its history on the peopling of an environmentally hostilecontinent.Africanshavebeenpioneersstrugglingagainstdiseaseandnature, and their social, economic, and political institutions have been designed to ensure their survival. In the context of medical progress and other twentieth-century innovations, however, the same institutions have bred the most rapid population growth the world has ever seen. The history of the continent is thus a single story binding living Africans to their earliest human ancestors. John Iliffe was Professor of African History at the University of Cambridge and is a Fellow of St. John’s College. He is the author of several books on Africa, including Amodern history of Tanganyika and The African poor: A history,which was awarded the Herskovits Prize of the African Studies Association of the United States. Both books were published by Cambridge University Press. i P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 ii P1: RNK 0521864381pre CUNY780B-African 978 0 521 68297 8 May 15, 2007 19:34 african studies The African Studies Series,founded in 1968 in collaboration with the African Studies Centre of the University of Cambridge, is a prestigious series of monographs and general studies on Africa covering history, anthropology, economics, sociology, and political science. -

History of Djibouti

History of Djibouti Nomadic herds people have inhabited the territory now belonging to Djibouti for millennia. The Issas and the Afars, the nation’s two major ethnic groups today, lived there when Arab traders introduced Islam to the area in the ninth century AD. Arabs at the port of Adal at Zeila (in modern-day Somalia) controlled the region until Adal’s collapse in 1543.Small Afar sultanates at Obock, Tadjoura, and elsewhere then emerged as the dominant powers. Frenchman Rochet d’Hericourt’s 1839 to 1842 exploration into Shoa marked the beginning of French interest in the region. Hoping to counter British influence on the other side of the Gulf of Aden, the French signed a treaty with the Afar sultan of Obock to establish a port in 1862. This led to the formation of French Somaliland in 1888. The construction of the Franco-Ethiopian Railway from Djibouti City to Ethiopia began in 1897 and finally reached Addis Ababa in 1917. The railroad opened up the interior of French Somaliland, which in1946 was given the status of an overseas French territory. By the 1950s, the Issas (a Somali clan) began to support the movement for the independence and unification of the region’s three Somali-populated colonies: French, British, and Italian Somaliland. In 1960, British and Italian Somaliland were granted independence and united to form the nation of Somalia, but France retained its hold on French Somaliland. When French president Charles de Gaulle visited French Somaliland in August 1966, he was met with two days of protests. The French announced that a referendum on independence would be held but also arrested independence leaders and expelled their supporters. -

RCS Demographics V2.0 Codebook

Religious Characteristics of States Dataset Project Demographics, version 2.0 (RCS-Dem 2.0) CODE BOOK Davis Brown Non-Resident Fellow Baylor University Institute for Studies of Religion [email protected] Acknowledgements I would like to thank the following persons for their assistance, without which this project could not have been completed. First and foremost, my co-principal investigator, Patrick James. Among faculty and researchers, I thank Brian Bergstrom, Peter W. Brierley, Peter Crossing, Abe Gootzeit, Todd Johnson, Barry Sang, and Sanford Silverburg. I also thank the library staffs of the following institutions: Assembly of God Theological Seminary, Catawba College, Maryville University of St. Louis, St. Louis Community College System, St. Louis Public Library, University of Southern California, United States Air Force Academy, University of Virginia, and Washington University in St. Louis. Last but definitely not least, I thank the following research assistants: Nolan Anderson, Daniel Badock, Rebekah Bates, Matt Breda, Walker Brown, Marie Cormier, George Duarte, Dave Ebner, Eboni “Nola” Haynes, Thomas Herring, and Brian Knafou. - 1 - TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 3 Citation 3 Updates 3 Territorial and Temporal Coverage 4 Regional Coverage 4 Religions Covered 4 Majority and Supermajority Religions 6 Table of Variables 7 Sources, Methods, and Documentation 22 Appendix A: Territorial Coverage by Country 26 Double-Counted Countries 61 Appendix B: Territorial Coverage by UN Region 62 Appendix C: Taxonomy of Religions 67 References 74 - 2 - Introduction The Religious Characteristics of States Dataset (RCS) was created to fulfill the unmet need for a dataset on the religious dimensions of countries of the world, with the state-year as the unit of observation. -

WANSALAWARA Soundings in Melanesian History

WANSALAWARA Soundings in Melanesian History Introduced by BRIJ LAL Working Paper Series Pacific Islands Studies Program Centers for Asian and Pacific Studies University of Hawaii at Manoa EDITOR'S OOTE Brij Lal's introduction discusses both the history of the teaching of Pacific Islands history at the University of Hawaii and the origins and background of this particular working paper. Lal's comments on this working paper are quite complete and further elaboration is not warranted. Lal notes that in the fall semester of 1983, both he and David Hanlon were appointed to permanent positions in Pacific history in the Department of History. What Lal does not say is that this represented a monumental shift of priorities at this University. Previously, as Lal notes, Pacific history was taught by one individual and was deemed more or less unimportant. The sole representative maintained a constant struggle to keep Pacific history alive, but the battle was always uphill. The year 1983 was a major, if belated, turning point. Coinciding with a national recognition that the Pacific Islands could no longer be ignored, the Department of History appointed both Lal and Hanlon as assistant professors. The two have brought a new life to Pacific history at this university. New courses and seminars have been added, and both men have attracted a number of new students. The University of Hawaii is the only American university that devotes serious attention to Pacific history. Robert,C. Kiste Director Center for Pacific Islands Studies WANSALAWARA Soundings in Melanesian History Introduced by BRIJ V. LAL 1987 " TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. -

Mise En Page 1

[]Annual Report 2004 Legalmentions Published by : IUCN Regional Office for West Africa, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso © 2005 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowled- ged. Citation : IUCN-BRAO (2005). Annual Report 2004, Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. 34 pp. ISBN : 2-8317-0851-6 Cover photos : J.F. Hellion N. Van Ingen - FIBA IUCN Jean-Marc GARREAU Louis Gérard d’ESCRIENNE Design and layout by : DIGIT’ART Printed by : Ghana Printing & Packaging Industries LTD Available from : IUCN-regional office for West Africa 01 BP 1618 Ouagadougou 01 Burkina Faso Tél.: (226) 50 32 85 00 Fax : (226) 50 30 75 61 E-mail : [email protected] Website : www.iucn.org/brao IUCN []3 []Annual Report 2004 Contents 6 Foreword Substantial Development of the Regional Programme in 2004 8 IUCN donors A Standing Support 10 Four Years in West Africa 10 - Introduction 12 - The Regional Wetlands Programme 15 - Economic and Social Equity as Core Principle of Conservation 18 - Creating Dialogue for Influencing Policies 21 - WAP transboundary Complex Protecting the Environment is “ to guarantee social and economic livelihood 24 West Africa at the Bangkok Congress IUCN-BRAO took part in the Bangkok World Conservation Congress “ of populations in West Africa 26 Programme Development prospects for IUCN West Africa 26 - The New Four-Year Programme 31 - The PRCM is moving forward 32 Annexes 32 - Financial Reports 33 - Recent Publications 33 - List of IUCN Members in West Africa 34 - IUCN Offices []4 REGIONAL OFFICE FOR WEST AFRICA IUCN []5 []Annual Report 2004 West Africa Members, up to date with the Foreword bylaws of the Organisation, were all represented at this meeting. -

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by the Office Of

RECORDS CODIFICATION MANUAL Prepared by The Office of Communications and Records Department of State (Adopted January 1, 1950—Revised January 1, 1955) I I CLASSES OF RECORDS Glass 0 Miscellaneous. I Class 1 Administration of the United States Government. Class 2 Protection of Interests (Persons and Property). I Class 3 International Conferences, Congresses, Meetings and Organizations. United Nations. Organization of American States. Multilateral Treaties. I Class 4 International Trade and Commerce. Trade Relations, Treaties, Agreements. Customs Administration. Class 5 International Informational and Educational Relations. Cultural I Affairs and Programs. Class 6 International Political Relations. Other International Relations. I Class 7 Internal Political and National Defense Affairs. Class 8 Internal Economic, Industrial and Social Affairs. 1 Class 9 Other Internal Affairs. Communications, Transportation, Science. - 0 - I Note: - Classes 0 thru 2 - Miscellaneous; Administrative. Classes 3 thru 6 - International relations; relations of one country with another, or of a group of countries with I other countries. Classes 7 thru 9 - Internal affairs; domestic problems, conditions, etc., and only rarely concerns more than one I country or area. ' \ \T^^E^ CLASS 0 MISCELLANEOUS 000 GENERAL. Unclassifiable correspondence. Crsnk letters. Begging letters. Popular comment. Public opinion polls. Matters not pertaining to business of the Department. Requests for interviews with officials of the Department. (Classify subjectively when possible). Requests for names and/or addresses of Foreign Service Officers and personnel. Requests for copies of treaties and other publications. (This number should never be used for communications from important persons, organizations, etc.). 006 Precedent Index. 010 Matters transmitted through facilities of the Department, .1 Telegrams, letters, documents. -

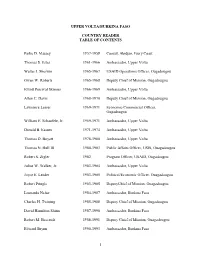

Upper Volta/Burkina Faso Country Reader Table Of

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast homas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper (olta )alter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID ,perations ,ffi.er, ,ugadougou ,wen ). 0oberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,ugadougou Elliott Per.ival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper (olta Allen C. Davis 1968-1971 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,ugadougou 2awren.e 2esser 1969-1971 E.onomi.3Commer.ial ,ffi.er, ,ugadougou )illiam E. S.haufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper (olta Donald 4. Easum 1971-1975 Ambassador, Upper (olta homas D. 4oyatt 1978-1981 Ambassador, Upper (olta 0obert S. 6igler 1982 Program ,ffi.er, USAID, ,ugadougou Julius ). )alker, Jr. 1988-1985 Ambassador, Upper (olta Joy.e E. 2eader 1988-1985 Politi.al3E.onomi. ,ffi.er, ,uagadougou 2eonardo Neher 1985-1987 Ambassador, 4urkina :aso Charles H. wining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,ugadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1991 Ambassador, 4urkina :aso 0obert M. 4ee.rodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, ,uagadougou Edward 4rynn 1991-1998 Ambassador, 4urkina :aso PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidj n, Ivory Co st (1957-195,- Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford Co ege with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He a so served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Me-ico City, .enoa, Abid/an, and .ermany. 0hi e in USA1D, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bo ivia, Chi e, Haiti, and Uruguay. -

Abdallahi Ibn Muhammad, 139 Abdelhafid, Sultan of Morocco, 416

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48382-7 — Learning Empire Erik Grimmer-Solem Index More Information INDEX Abdallahi ibn Muhammad, 139 extension services, 395 Abdelhafid, sultan of Morocco, 416 horticulture, 47 Abdul Hamid II, sultan of the Ottoman Landflucht, 43 Empire, 299 livestock, 43, 55, 72, 229, 523, 564 Abyssinia, 547 maize, 155, 229 acclimatization question. See tropics milling, 70, 240 Achenbach, Heinrich, 80–81 oil seeds, 55 Adams, Henry, 32, 316 peasants, 55–56, 184, 272–73, 275, Adana, 363, 365 427, 429, 433, 559–60 Addams, Jane, 70 reforms of, 429 Addis Ababa, 547 rice, 88, 105, 529 Aden, 87, 139, 245, 546 rubber, 408–9, 412, 414, 416, 421, Adenauer, Konrad, 602 426, 445 Adrianople, 486, 491 rye, 55, 273, 279, 522, 525 Afghanistan, 120, 176, 324 sugar, 55, 78, 155, 204, 380, 385, Africa, German 411–12, 416, 423, 445 See also Cameroon, East Africa; tea, 412 Herero and Nama wars; Maji tobacco, 76, 152, 204, 379–80, Maji rebellion; Southwest 412–14, 416, 423, 445 Africa; Togo wheat, 43, 46–47, 49–50, 53, 55, 59, Agadir Crisis (1911), 376, 406, 416–17, 69, 71, 229, 520, 522, 525, 528, 437, 456–57, 479, 486, 500 561, 579 Agrarian League (Bund der Landwirte), See also colonial science; cotton 469, 471, 473, 477 industry; inner colonization; agriculture rubber industry; sugar industry; barley, 47, 55, 523 tobacco industry cacao, 152, 155 Ahmad bin Abd Allah, Muhammad, 139 coconuts, 218 Alabama, 378 coffee, 145, 152, 155, 204, 273, 412 See also Calhoun Colored School; copra, 218 Tuskegee Institute cotton, 67, 74–75, 151, 158, 204, -

Research Master Thesis

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? Understanding how and why new ICTs played a role in Burkina Faso’s recent journey to socio-political change Fiona Dragstra, M.Sc. Research Master Thesis Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose? Understanding how and why new ICTs played a role in Burkina Faso’s recent journey to socio-political change Research Master Thesis By: Fiona Dragstra Research Master African Studies s1454862 African Studies Centre, Leiden Supervisors: Prof. dr. Mirjam de Bruijn, Leiden University, Faculty of History dr. Meike de Goede, Leiden University, Faculty of History Third reader: dr. Sabine Luning, Leiden University, Faculty of Social Sciences Date: 14 December 2016 Word count (including footnotes): 38.339 Cover photo: Young woman protests against the coup d’état in Bobo-Dioulasso, September 2015. Photo credit: Lefaso.net and @ful226, Twitter, 20 September 2015 All pictures and quotes in this thesis are taken with and used with consent of authors and/or people on pictures 1 A dedication to activists – the Burkinabè in particular every protest. every voice. every sound. we have made. in the protection of our existence. has shaken the entire universe. it is trembling. Nayyirah Waheed – a poem from her debut Salt Acknowledgements Together we accomplish more than we could ever do alone. My fieldwork and time of writing would have never been as successful, fruitful and wonderful without the help of many. First and foremost I would like to thank everyone in Burkina Faso who discussed with me, put up with me and helped me navigate through a complex political period in which I demanded attention and precious time, which many people gave without wanting anything in return. -

Table of Contents

UPPER VOLTA/BURKINA FASO COUNTRY READER TABLE OF CONTENTS Parke D. Massey 1957-1958 Consul, Abidjan, Ivory Coast Thomas S. Estes 1961-1966 Ambassador, Upper Volta Walter J. Sherwin 1965-1967 USAID Operations Officer, Ougadougou Owen W. Roberts 1965-1968 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Elliott Percival Skinner 1966-1969 Ambassador, Upper Volta Allen C. Davis 1968-1970 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou Lawrence Lesser 1969-1971 Economic/Commercial Officer, Ougadougou William E. Schaufele, Jr. 1969-1971 Ambassador, Upper Volta Donald B. Easum 1971-1974 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas D. Boyatt 1978-1980 Ambassador, Upper Volta Thomas N. Hull III 1980-1983 Public Affairs Officer, USIS, Ouagadougou Robert S. Zigler 1982 Program Officer, USAID, Ougadougou Julius W. Walker, Jr. 1983-1984 Ambassador, Upper Volta Joyce E. Leader 1983-1985 Political/Economic Officer, Ouagadougou Robert Pringle 1983-1985 DeputyChief of Mission, Ouagadougou Leonardo Neher 1984-1987 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Charles H. Twining 1985-1988 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ougadougou David Hamilton Shinn 1987-1990 Ambassador, Burkina Faso Robert M. Beecrodt 1988-1991 Deputy Chief of Mission, Ouagadougou Edward Brynn 1990-1993 Ambassador, Burkina Faso 1 PARKE D. MASSEY Consul Abidjan, Ivory Coast (1957-1958) Parke D. Massey was born in New York in 1920. He graduated from Haverford College with a B.A. and Harvard University with an M.P.A. He also served in the U.S. Army from 1942 to 1946 overseas. After entering the Foreign Service in 1947, Mr. Massey was posted in Mexico City, Genoa, Abidjan, and Germany. While in USAID, he was posted in Nicaragua, Panama, Bolivia, Chile, Haiti, and Uruguay. -

(CMF) and the Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCOC) Aimed at Maintaining Maritime Security in the Area of the Western Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Aden

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 11-3-2020 A comparative study of the Combined Maritime Force (CMF) and the Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCOC) aimed at maintaining maritime security in the area of the western Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Aden Abdullah Mohammed Mubaraki Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Part of the Defense and Security Studies Commons, and the Law of the Sea Commons Recommended Citation Mubaraki, Abdullah Mohammed, "A comparative study of the Combined Maritime Force (CMF) and the Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCOC) aimed at maintaining maritime security in the area of the western Indian Ocean and the Gulf of Aden" (2020). World Maritime University Dissertations. 1386. https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/1386 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non-commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmö, Sweden A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE COMBINED MARITIME FORCE (CMF) AND THE DJIBOUTI CODE OF CONDUCT (DCOC) AIMED AT MAINTAINING MARITIME SECURITY IN THE AREA OF THE WESTERN INDIAN OCEAN AND THE GULF OF ADEN By ABDULLAH MOHAMMED MUBARAKI KINGDOM OF SAUDI ARABIA A dissertation submitted to the World Maritime University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the reward of the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in MARITIME AFFAIRS (MARITIME SAFETY AND ENVIRONMENTAL ADMINISTRATION) 2020 Copyright Abdullah Mubaraki, 2020 Declaration I certify that all the material in this dissertation that is not my own work has been identified, and that no material is included for which a degree has previously been conferred on me.