1 ANDEAN MUSIC ENSEMBLE Autumn 2020 – Hybrid Course

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Kjarkas Historia Jamás Contada

LOS KJARKAS: LA HISTORIA NO CONTADA LOS KJARKAS Actual formación de Los Kjarkas Introducción: Los más grandes de entre los grandes, los músicos andinos que han llevado al folklore latinoamericano a lo más alto, son sin duda alguna Los Kjarkas, un grupo que revolucionó el arte musical andino hace ya casi 50 años y que a lo largo de toda una vida nos han deleitado con impagables obras maestras con mayúsculas. Y es que todo en Los Kjarkas es grandioso: grandes músicos, grandes composiciones y una gran historia, por él han pasado intérpretes y compositores de gran calibre, manteniendo siempre un núcleo familiar en torno a la familia Hermosa. Sin embargo, no todo ha sido alegría, comprensión u honestidad dentro del grupo. En muchos foros, entrevistas o videos, se habla sobre la historia de los Kjarkas, pero se ha omitido gran parte de esta historia, historia que leerás hoy día. Es esta pues, la historia oculta de Los Kjarkas. LOS KJARKAS: LA HISTORIA NO CONTADA Advertencias: - Si eres una persona conservadora, un fanático a morir de Los Kjarkas, que los ve como “ídolos”, que no podrían hacer malo, y no deseas “tener” una mala imagen de ellos, te pido que dejes de leer este artículo, porque podrías cambiar de mirada y llevarte un gran disgusto. - Durante la historia, se nombrarán a otros grupos, que son necesarios de nombrar para poder entender la historia de Los Kjarkas. LOS KJARKAS: LA HISTORIA NO CONTADA Etimología del nombre: Sobre el nombre “Kjarkas” no hay nada dicho ciertamente. Se manejan dos significados y orígenes que se contradicen. -

Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: a Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Master's Theses Graduate College 4-2012 Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: A Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo Brenna C. Halpin Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons Recommended Citation Halpin, Brenna C., "Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: A Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo" (2012). Master's Theses. 50. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/masters_theses/50 This Masters Thesis-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (/AV%\ C FLUTES, FESTIVITIES, AND FRAGMENTED TRADITION: A STUDY OF THE MEANING OF MUSIC IN OTAVALO by: Brenna C. Halpin A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty ofThe Graduate College in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Degree ofMaster ofArts School ofMusic Advisor: Matthew Steel, Ph.D. Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2012 THE GRADUATE COLLEGE WESTERN MICHIGAN UNIVERSITY KALAMAZOO, MICHIGAN Date February 29th, 2012 WE HEREBY APPROVE THE THESIS SUBMITTED BY Brenna C. Halpin ENTITLED Flutes, Festivities, and Fragmented Tradition: A Study of the Meaning of Music in Otavalo AS PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE Master of Arts DEGREE OF _rf (7,-0 School of Music (Department) Matthew Steel, Ph.D. Thesis Committee Chair Music (Program) Martha Councell-Vargas, D.M.A. Thesis Committee Member Ann Miles, Ph.D. Thesis Committee Member APPROVED Date .,hp\ Too* Dean of The Graduate College FLUTES, FESTIVITIES, AND FRAGMENTED TRADITION: A STUDY OF THE MEANING OF MUSIC IN OTAVALO Brenna C. -

WORKSHOP: Around the World in 30 Instruments Educator’S Guide [email protected]

WORKSHOP: Around The World In 30 Instruments Educator’s Guide www.4shillingsshort.com [email protected] AROUND THE WORLD IN 30 INSTRUMENTS A MULTI-CULTURAL EDUCATIONAL CONCERT for ALL AGES Four Shillings Short are the husband-wife duo of Aodh Og O’Tuama, from Cork, Ireland and Christy Martin, from San Diego, California. We have been touring in the United States and Ireland since 1997. We are multi-instrumentalists and vocalists who play a variety of musical styles on over 30 instruments from around the World. Around the World in 30 Instruments is a multi-cultural educational concert presenting Traditional music from Ireland, Scotland, England, Medieval & Renaissance Europe, the Americas and India on a variety of musical instruments including hammered & mountain dulcimer, mandolin, mandola, bouzouki, Medieval and Renaissance woodwinds, recorders, tinwhistles, banjo, North Indian Sitar, Medieval Psaltery, the Andean Charango, Irish Bodhran, African Doumbek, Spoons and vocals. Our program lasts 1 to 2 hours and is tailored to fit the audience and specific music educational curriculum where appropriate. We have performed for libraries, schools & museums all around the country and have presented in individual classrooms, full school assemblies, auditoriums and community rooms as well as smaller more intimate settings. During the program we introduce each instrument, talk about its history, introduce musical concepts and follow with a demonstration in the form of a song or an instrumental piece. Our main objective is to create an opportunity to expand people’s understanding of music through direct expe- rience of traditional folk and world music. ABOUT THE MUSICIANS: Aodh Og O’Tuama grew up in a family of poets, musicians and writers. -

C:\010 MWP-Sonderausgaben (C)\D

Dancando Lambada Hintergründe von S. Radic "Dançando Lambada" is a song of the French- Brazilian group Kaoma with the Brazilian singer Loalwa Braz. It was the second single from Kaomas debut album Worldbeat and followed the world hit "Lambada". Released in October 1989, the album peaked in 4th place in France, 6th in Switzerland and 11th in Ireland, but could not continue the success of the previous hit single. A dub version of "Lambada" was available on the 12" and CD maxi. In 1976 Aurino Quirino Gonçalves released a song under his Lambada-Original is the title of a million-seller stage name Pinduca under the title "Lambada of the international group Kaoma from 1989, (Sambão)" as the sixth title on his LP "No embalo which has triggered a dance wave with the of carimbó and sirimbó vol. 5". Another Brazilian dance of the same name. The song Lambada record entitled "Lambada das Quebradas" was is actually a plagiarism, because music and then released in 1978, and at the end of 1980 parts of the lyrics go back to the original title several dance halls were finally created in Rio de "Llorando se fue" ("Crying she went") of the Janeiro and other Brazilian cities under the name Bolivian folklore group Los Kjarkas from the "Lambateria". Márcia Ferreira then remembered Municipio Cochabamba. She had recorded this forgotten Bolivian song in 1986 and recorded the song composed by Ulises Hermosa and a legal Portuguese cover version for the Brazilian his brother Gonzalo Hermosa-Gonzalez, to market under the title Chorando se foi (same which they dance Saya in Bolivia, for their meaning as the Spanish original) with Portuguese 1981 LP Canto a la mujer de mi pueblo, text; but even this version remained without great released by EMI. -

The Global Charango

The Global Charango by Heather Horak A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020 Heather Horak i Abstract Has the charango, a folkloric instrument deeply rooted in South American contexts, “gone global”? If so, how has this impacted its music and meaning? The charango, a small and iconic guitar-like chordophone from Andes mountains areas, has circulated far beyond these homelands in the last fifty to seventy years. Yet it remains primarily tied to traditional and folkloric musics, despite its dispersion into new contexts. An important driver has been the international flow of pan-Andean music that had formative hubs in Central and Western Europe through transnational cosmopolitan processes in the 1970s and 1980s. Through ethnographies of twenty-eight diverse subjects living in European fields (in Austria, France, Belgium, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Croatia, and Iceland) I examine the dynamic intersections of the instrument in the contemporary musical and cultural lives of these Latin American and European players. Through their stories, I draw out the shifting discourses and projections of meaning that the charango has been given over time, including its real and imagined associations with indigineity from various positions. Initial chapters tie together relevant historical developments, discourses (including the “origins” debate) and vernacular associations as an informative backdrop to the collected ethnographies, which expose the fluidity of the instrument’s meaning that has been determined primarily by human proponents and their social (and political) processes. -

HISPANIC MUSIC for BEGINNERS Terminology Hispanic Culture

HISPANIC MUSIC FOR BEGINNERS PETER KOLAR, World Library Publications Terminology Spanish vs. Hispanic; Latino, Latin-American, Spanish-speaking (El) español, (los) españoles, hispanos, latinos, latinoamericanos, habla-español, habla-hispana Hispanic culture • A melding of Spanish culture (from Spain) with that of the native Indian (maya, inca, aztec) Religion and faith • popular religiosity: día de los muertos (day of the dead), santería, being a guadalupano/a • “faith” as expession of nationalistic and cultural pride in addition to spirituality Diversity within Hispanic cultures Many regional, national, and cultural differences • Mexican (Southern, central, Northern, Eastern coastal) • Central America and South America — influence of Spanish, Portuguese • Caribbean — influence of African, Spanish, and indigenous cultures • Foods — as varied as the cultures and regions Spanish Language Basics • a, e, i, o, u — all pure vowels (pronounced ah, aey, ee, oh, oo) • single “r” vs. rolled “rr” (single r is pronouced like a d; double r = rolled) • “g” as “h” except before “u” • “v” pronounced as “b” (b like “burro” and v like “victor”) • “ll” and “y” as “j” (e.g. “yo” = “jo”) • the silent “h” • Elisions (spoken and sung) of vowels (e.g. Gloria a Dios, Padre Nuestro que estás, mi hijo) • Dipthongs pronounced as single syllables (e.g. Dios, Diego, comunión, eucaristía, tienda) • ch, ll, and rr considered one letter • Assigned gender to each noun • Stress: on first syllable in 2-syllable words (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) • Stress: on penultimate syllable in 3 or more syllables (except if ending in “r,” “l,” or “d”) Any word which doesn’t follow these stress rules carries an accent mark — é, á, í, ó, étc. -

Explorer's Guide Peruvian Music

EXPLORER’S GUIDE PERUVIAN MUSIC A shaman plays a flute alongside Amazonian Peru’s Boiling River. Facing the 1 2 3 4 Music in Hidden Workshop Andes Anthems Dinner and a Show Electric Inca Inside a storefront sign- Traditional Andean What originated as leftist, Follow up the show with Cusco posted simply “Luthier,” music isn’t something you anti-dictatorship music drinks and dancing at this expertly made Andean stumble across—it has to in the 1960s and ’70s has local staple for Andean While living among the instruments lie scattered be sought out. Wissler sug- morphed into Andean rock. Ukukus has live shows Q’eros, an indigenous around their maker. Sabino gests contacting Santos folk, supported by guitar, daily, while Sundays are Andean group in south- Huamán, a third-generation Machacca Apaza, a Q’ero, charango, various flutes, headlined by Amaru Puma east Peru, Holly Wissler stringed instrument crafts- to sit in on an offering to and drums. “People love it,” Kuntur, a band named for was immersed in their man, will demonstrate how apus (mountain gods) and says Wissler of the haunt- the three cosmic figures native music. Now based to play each charango, Pachamama (Mother Earth) ing melodies, which are of the Inca Empire (snake, in Cusco, the ethno- bandurria, guitar, and at his family’s home, 20 best enjoyed over dinner at puma, and condor). Here, musicologist and Nat quena flute. Ask to see his minutes outside Cusco. any number of restaurants folk music goes electric, Geo Expeditions expert workshop upstairs, says Request music up front so in Cusco, including the with hand pipes and quena outlines where to find Wissler—and even if you that his mother is around just opened Ayasqa, which flutes getting the rock- the best local beats. -

Spanish 7780.22 Revised 6-15-15.Pdf

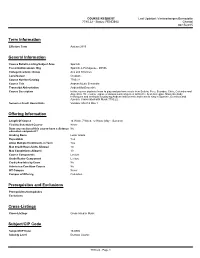

COURSE REQUEST Last Updated: Vankeerbergen,Bernadette 7780.22 - Status: PENDING Chantal 06/15/2015 Term Information Effective Term Autumn 2015 General Information Course Bulletin Listing/Subject Area Spanish Fiscal Unit/Academic Org Spanish & Portuguese - D0596 College/Academic Group Arts and Sciences Level/Career Graduate Course Number/Catalog 7780.22 Course Title Andean Music Ensemble Transcript Abbreviation AndeanMusEnsemble Course Description In this course students learn to play and perform music from Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia and Argentina. The course explores various musical genres within the Andean region. Students study techniques and methods for playing Andean instruments and learn to sing in Spanish, Quechua and Aymara. Cross-listed with Music 7780.22. Semester Credit Hours/Units Variable: Min 0.5 Max 1 Offering Information Length Of Course 14 Week, 7 Week, 12 Week (May + Summer) Flexibly Scheduled Course Never Does any section of this course have a distance No education component? Grading Basis Letter Grade Repeatable Yes Allow Multiple Enrollments in Term Yes Max Credit Hours/Units Allowed 10 Max Completions Allowed 10 Course Components Lecture Grade Roster Component Lecture Credit Available by Exam No Admission Condition Course No Off Campus Never Campus of Offering Columbus Prerequisites and Exclusions Prerequisites/Corequisites Exclusions Cross-Listings Cross-Listings Cross-listed in Music Subject/CIP Code Subject/CIP Code 16.0905 Subsidy Level Doctoral Course 7780.22 - Page 1 COURSE REQUEST Last Updated: Vankeerbergen,Bernadette 7780.22 - Status: PENDING Chantal 06/15/2015 Intended Rank Masters, Doctoral, Professional Requirement/Elective Designation The course is an elective (for this or other units) or is a service course for other units Course Details Course goals or learning • To become familiar with a range of Andean music genres through an applied approach to music performance. -

Prek–12 EDUCATOR RESOURCES QUICK GUIDE

PreK–12 EDUCATOR RESOURCES QUICK GUIDE MUSICAL INSTRUMENT MUSEUM BRING THE WORLD OF MUSIC TO THE CLASSROOM MIM’s Educator Resources are meant to deepen and extend the learning that takes place on a field trip to the museum. Prekindergarten through 12th-grade educators can maximize their learning objectives with the following resources: • Downloadable hands-on activities and lesson plans • Digital tool kits with video clips and photos • Background links, articles, and information for educators • Free professional development sessions at MIM Each interdisciplinary tool kit focuses on a gallery, display, musical instrument, musical style, or cultural group—all found at MIM: the most extraordinary museum you’ll ever experience! RESOURCES ARE STANDARDS-BASED: Arizona K–12 Academic Standards • English Language Arts • Social Studies • Mathematics • Science • Music • Physical Education Arizona Early Learning Standards • English Language Arts • Social Studies • Mathematics • Science • Music • Physical Education EXPLORE MIM’S EDUCATOR RESOURCES ONLINE: • Schedule a field trip to MIM • Download prekindergarten through 12th-grade tool kits • Register for free professional development at MIM MIM.org | 480.478.6000 | 4725 E. Mayo Blvd., Phoenix, AZ 85050 (Corner of Tatum & Mayo Blvds., just south of Loop 101) SOUNDS ALL AROUND Designed by MIM Education MUSICAL INSTRUMENT MUSEUM SUMMARY Tool Kits I–III feature activities inspired by MIM’s collections and Geographic Galleries as well as culturally diverse musical selections. They are meant to extend and -

Contemporary Muisca Indigenous Sounds in the Colombian Andes

Nymsuque: Contemporary Muisca Indigenous Sounds in the Colombian Andes Beatriz Goubert Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2019 © 2019 Beatriz Goubert All rights reserved ABSTRACT Nymsuque: Contemporary Muisca Indigenous Sounds in the Colombian Andes Beatriz Goubert Muiscas figure prominently in Colombian national historical accounts as a worthy and valuable indigenous culture, comparable to the Incas and Aztecs, but without their architectural grandeur. The magnificent goldsmith’s art locates them on a transnational level as part of the legend of El Dorado. Today, though the population is small, Muiscas are committed to cultural revitalization. The 19th century project of constructing the Colombian nation split the official Muisca history in two. A radical division was established between the illustrious indigenous past exemplified through Muisca culture as an advanced, but extinct civilization, and the assimilation politics established for the indigenous survivors, who were considered degraded subjects to be incorporated into the national project as regular citizens (mestizos). More than a century later, and supported in the 1991’s multicultural Colombian Constitution, the nation-state recognized the existence of five Muisca cabildos (indigenous governments) in the Bogotá Plateau, two in the capital city and three in nearby towns. As part of their legal battle for achieving recognition and maintaining it, these Muisca communities started a process of cultural revitalization focused on language, musical traditions, and healing practices. Today’s Muiscas incorporate references from the colonial archive, archeological collections, and scholars’ interpretations of these sources into their contemporary cultural practices. -

Augmented Charango: an Instrument for Enriching the Andean Music Social Role

Proceedings of the 11th International Conference of Students of Systematic Musicology AUGMENTED CHARANGO: AN INSTRUMENT FOR ENRICHING THE ANDEAN MUSIC SOCIAL ROLE Julian Jaramillo Arango Jaime Daniel Rojas Núcleo de Sonologia Independent Researcher Escola de Comunicações e Artes [email protected] Universidade de São Paulo [email protected] ABSTRACT interaction, as well as links between theoretical and practical endeavours. Departing from Thomas Turino’s research about the context of the charango (Andean stringed instrument) in This work in progress research described in the paper is rural Peru which is highly symbolic and relates to divided into four parts. In the first section we will present processes of courting and love and using it as an a historical context by recognizing pertinent references in inspiration, our aim is to create a new interface design for our region concerned with indigenous music making and the charango that expands its social possibilities yet to be new technologies. Then we will have an explanation of determined. An electronic extension of the instrument the research project in the second section, here we will will be incorporated which enables the player to get new present the proposal of a four stage plan for the research. layers of sounds serving as a new development of the Afterwards we will talk about the strumming technique NIME (New Instruments for Musical Expression), human and justify why it is the focus of the research. Finally in computer interaction and computer music. Schachter’s the last section we will discuss some activities and work on live electronics and the cajon (a Peruvian procedures we envision in future stages of the project. -

Imagined Landscapes and Virtual Locality in Indigenous Andean Music Video Trans

Trans. Revista Transcultural de Música E-ISSN: 1697-0101 [email protected] Sociedad de Etnomusicología España Stobart, Henry Dancing in the Fields: Imagined Landscapes and Virtual Locality in Indigenous Andean Music Video Trans. Revista Transcultural de Música, núm. 20, 2016, pp. 1-29 Sociedad de Etnomusicología Barcelona, España Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=82252822008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative TRANS 20 (2016) DOSSIER: INDIGENOUS MUSICAL PRACTICES AND POLITICS IN LATIN AMERICA Dancing in the Fields: Imagined Landscapes and Virtual Locality in Indigenous Andean Music Videos Henry Stobart (Royal Holloway, University of London) Resumen Abstract El paso del casete de audio analógico al VCD (Video Compact Disc) The move from analogue audio cassette to digital VCD (Video Compact digital como soporte principal para la música gravada alrededor del Disc) in around 2003, as a primary format for recorded music, opened año 2003, abrió una nueva era para la producción y el consumo de up a new era for music production and consumption in the Bolivian música en la región de los Andes bolivianos. Esta tecnología digital Andes. This cheap digital technology both created new regional markets barata creó nuevos mercados regionales para los pueblos indígenas among low-income indigenous people, quickly making it almost de bajos ingresos, haciendo impensable para los artistas regionales unthinkable for regional artists to produce a commercial music producir una grabación comercial sin imágenes de vídeo desde recording without video images.