Imagined Landscapes and Virtual Locality in Indigenous Andean Music Video Trans

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Los Kjarkas Historia Jamás Contada

LOS KJARKAS: LA HISTORIA NO CONTADA LOS KJARKAS Actual formación de Los Kjarkas Introducción: Los más grandes de entre los grandes, los músicos andinos que han llevado al folklore latinoamericano a lo más alto, son sin duda alguna Los Kjarkas, un grupo que revolucionó el arte musical andino hace ya casi 50 años y que a lo largo de toda una vida nos han deleitado con impagables obras maestras con mayúsculas. Y es que todo en Los Kjarkas es grandioso: grandes músicos, grandes composiciones y una gran historia, por él han pasado intérpretes y compositores de gran calibre, manteniendo siempre un núcleo familiar en torno a la familia Hermosa. Sin embargo, no todo ha sido alegría, comprensión u honestidad dentro del grupo. En muchos foros, entrevistas o videos, se habla sobre la historia de los Kjarkas, pero se ha omitido gran parte de esta historia, historia que leerás hoy día. Es esta pues, la historia oculta de Los Kjarkas. LOS KJARKAS: LA HISTORIA NO CONTADA Advertencias: - Si eres una persona conservadora, un fanático a morir de Los Kjarkas, que los ve como “ídolos”, que no podrían hacer malo, y no deseas “tener” una mala imagen de ellos, te pido que dejes de leer este artículo, porque podrías cambiar de mirada y llevarte un gran disgusto. - Durante la historia, se nombrarán a otros grupos, que son necesarios de nombrar para poder entender la historia de Los Kjarkas. LOS KJARKAS: LA HISTORIA NO CONTADA Etimología del nombre: Sobre el nombre “Kjarkas” no hay nada dicho ciertamente. Se manejan dos significados y orígenes que se contradicen. -

Tesita Chiletiña Listita Pal Exito

Universidad Austral de Chile Facultad de Filosofía y Humanidades Escuela de Historia y Ciencias Sociales Profesor Patrocinante: Karen Alfaro Monsalve Instituto Ciencias Sociales LA CANCIÓN DE PROTESTA EN EL CHILE ACTUAL: ANÁLISIS DEL MOVIMIENTO CULTURAL DE “TROVADORES INDEPENDIENTES” 2000-2011 Seminario de Título para optar al título de profesor de Historia y Ciencias Sociales ANDREA GIORETTI MALDONADO SANCHEZ Valdivia Octubre, 2011 TABLA DE CONTENIDOS CONTENIDO PÁGINA INTRODUCCION 4 CAPITULO I: FORMULACION DEL PROBLEMA 7 1.1 Idea de Investigación 7 1.2 Planteamiento del problema 8 1.3 Pregunta 10 1.4 Hipótesis 10 1.5 Objetivo General 10 1.6 Objetivos Específicos 10 CAPITULO II: MARCO METODOLÓGICO 2.1 Localización espacio-temporal de la investigación 11 2.2 Entidades de Interés 11 2.3 Variables que se medirán 12 2.4 Fuente de Datos 12 2.5 Procedimientos de recolección y análisis de datos 13 CAPITULO III: MARCO TEÒRICO: Música y política, Canción Protesta. Chile 1973-2010 3.1 Cultura, música y política: De la infraestructura a la superestructura 14 1.- Estudios Culturales en la disciplina histórica ¿Algo Nuevo? 22 3.2 Musicología y Música Popular: La juventud e identidad en América Latina 1.-La música popular en los estudios culturales: conceptualización y antecedentes 25 1.1.-Entre lo popular y lo formal: La validación de la música popular como campo de estudio. Antecedentes históricos. 28 2.-El estudio de la música popular en Latinoamérica: la diversidad musical de un continente diverso. 29 3.-La musicología en la historiografía: desde la escuela de los Annales a la Interdisciplinaridad. 35 4.-La semiótica: el nuevo paso de la musicología 38 5.- Los efectos de la música popular en la juventud latinoamericana: Formadora de identidad y pertenencia. -

C:\010 MWP-Sonderausgaben (C)\D

Dancando Lambada Hintergründe von S. Radic "Dançando Lambada" is a song of the French- Brazilian group Kaoma with the Brazilian singer Loalwa Braz. It was the second single from Kaomas debut album Worldbeat and followed the world hit "Lambada". Released in October 1989, the album peaked in 4th place in France, 6th in Switzerland and 11th in Ireland, but could not continue the success of the previous hit single. A dub version of "Lambada" was available on the 12" and CD maxi. In 1976 Aurino Quirino Gonçalves released a song under his Lambada-Original is the title of a million-seller stage name Pinduca under the title "Lambada of the international group Kaoma from 1989, (Sambão)" as the sixth title on his LP "No embalo which has triggered a dance wave with the of carimbó and sirimbó vol. 5". Another Brazilian dance of the same name. The song Lambada record entitled "Lambada das Quebradas" was is actually a plagiarism, because music and then released in 1978, and at the end of 1980 parts of the lyrics go back to the original title several dance halls were finally created in Rio de "Llorando se fue" ("Crying she went") of the Janeiro and other Brazilian cities under the name Bolivian folklore group Los Kjarkas from the "Lambateria". Márcia Ferreira then remembered Municipio Cochabamba. She had recorded this forgotten Bolivian song in 1986 and recorded the song composed by Ulises Hermosa and a legal Portuguese cover version for the Brazilian his brother Gonzalo Hermosa-Gonzalez, to market under the title Chorando se foi (same which they dance Saya in Bolivia, for their meaning as the Spanish original) with Portuguese 1981 LP Canto a la mujer de mi pueblo, text; but even this version remained without great released by EMI. -

La Voz Quechua

Lea el texto sobre una cantante famosa de Bolivia. Primero decida si las afirmaciones (1-9) son verdaderas (V) o falsas (F) y ponga una cruz () en la casilla correcta en la hoja de respuestas. A continuación identifique la frase en el texto que explica su decisión. Escriba las primeras 4 palabras de la frase en el espacio adecuado. Puede haber más de una posibilidad; escriba solo una. La primera (0) ya está hecha y sirve como modelo. La voz quechua 23 de julio de 2018 Luzmila Carpio (Qala Qala, 1949) no olvida el día en que cantó por primera vez. Tenía 11 años y era domingo. Ese día, dejaba su Qala Qala natal, una comunidad quechua del altiplano boliviano, por la ciudad de Oruro para participar en un programa de radio que cada semana abría su micro a niños intérpretes. Carpio ignoraba por completo cómo habían conseguido “hacer entrar cantantes en ese pequeño aparato”. Tampoco hablaba castellano. Empezó a entonar las primeras notas cuando un pianista le dio la tonalidad. Duró poco. “¡Esto lo cantan los indios! ¡Vuelve cuando sepas cantar en castellano!”, le gritó el hombre. Carpio abandonó el estudio bañada en lágrimas, pero decidida a volver a intentarlo el domingo siguiente. El pianista ignoraba que acababa de gritar a una niña que se convertiría en una de las figuras más destacadas de la música boliviana sin cantar en español, sino en el idioma de sus ancestros: el quechua. “Los indígenas siempre hemos sido marginados por nuestras lenguas, por nuestra manera de pensar, nuestra espiritualidad y más que todo por pertenecer a una cultura distinta”, explica Carpio sentada en el sofá de su apartamento parisino del barrio de Aligre, situado en el distrito 12 de la capital francesa. -

Disertación Final

PONTIFICIA UNIVERSIDAD CATÓLICA DEL ECUADOR FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS ADMINISTRATIVAS Y CONTABLES DESARROLLO DE UN PLAN ESTRATÉGICO DE MARKETING DE LA BANDA CUMBIA DEL BARRIO EN EL MERCADO MUSICAL DE LA CIUDAD DE QUITO TRABAJO DE TITULACIÓN PREVIA LA OBTENCIÓN DEL TÍTULO DE INGENIERÍA COMERCIAL LUIS ALBERTO ANDINO LÓPEZ DIRECTOR: ING. VICENTE TORRES QUITO, MAYO 2014 DIRECTOR DE DISERTACIÓN: Ing. Vicente Torres INFORMANTES: Ing. Jaime Benalcázar Mtr. Roberto Ordóñez ii DEDICATORIA Este trabajo está dedicado a mis padres, a todo el apoyo que me han brindado en estos años de estudio. Va dedicado a la gente que siempre me ayudó con su voluntad, su tiempo y esfuerzo para desarrollar este tema en especial una merecida dedicatoria a mis amigos de la "Cumbia del Barrio", Diana, Felipe, Leonardo, Julio, Fernando, Xavicho, Igor. Y todas aquellas personas que nos acompañaron en nuestra travesía musical. Alberto iii AGRADECIMIENTO A todas las personas que me acompañaron en este camino musical, a los amigos de la Cumbia del Barrio que estuvieron presentes en todos los conciertos que podían asistir. A aquellas personas que siempre estuvieron a mi lado brindándome su apoyo moral y sus conocimientos en este proyecto. Agradezco a aquellas personas y medios de comunicación que nos dieron la apertura para poder compartir nuestra música con el público en general, así mencionó a Radio La Luna, Radio Quito y en especial a su programa "Territorio Cumbia". Alberto iv ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN, 1 1 ANÁLISIS SITUACIONAL, 3 1.1 EL ENTORNO EXTERNO, 3 1.1.1 Competencia, 4 1.1.2 -

The Global Charango

The Global Charango by Heather Horak A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music and Culture Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020 Heather Horak i Abstract Has the charango, a folkloric instrument deeply rooted in South American contexts, “gone global”? If so, how has this impacted its music and meaning? The charango, a small and iconic guitar-like chordophone from Andes mountains areas, has circulated far beyond these homelands in the last fifty to seventy years. Yet it remains primarily tied to traditional and folkloric musics, despite its dispersion into new contexts. An important driver has been the international flow of pan-Andean music that had formative hubs in Central and Western Europe through transnational cosmopolitan processes in the 1970s and 1980s. Through ethnographies of twenty-eight diverse subjects living in European fields (in Austria, France, Belgium, Germany, Spain, Portugal, Switzerland, Croatia, and Iceland) I examine the dynamic intersections of the instrument in the contemporary musical and cultural lives of these Latin American and European players. Through their stories, I draw out the shifting discourses and projections of meaning that the charango has been given over time, including its real and imagined associations with indigineity from various positions. Initial chapters tie together relevant historical developments, discourses (including the “origins” debate) and vernacular associations as an informative backdrop to the collected ethnographies, which expose the fluidity of the instrument’s meaning that has been determined primarily by human proponents and their social (and political) processes. -

Videomemes Musicales, Punctum, Contrapunto Cognitivo Y Lecturas

“The Who live in Sinaloa”: videomemes musicales, punctum, contrapunto cognitivo y lecturas oblicuas “The Who live in Sinaloa”: Musical video memes, punctum, cognitive counterpoint and oblique readings por Rubén López-Cano Escola Superior de Música de Catalunya, España [email protected] Los internet memes son unidades culturales de contenido digital multimedia que se propagan inten- samente por la red en un proceso en el que son intervenidos, remezclados, adaptados, apropiados y transformados por sus usuarios una y otra vez. Su dispersión sigue estructuras, reglas, narrativas y argumentos que se matizan, intensifican o cambian constantemente dando lugar a conversaciones digi- tales de diverso tipo. Después de una introducción general a la memética, en este trabajo se analizan a fondo algunos aspectos del meme Cover Heavy cumbia. En este, los prosumidores montan escenas de conciertos de bandas de rock duro como Metallica, Korn o Guns N’ Roses, sobre músicas de escenas locales latinoamericanas como cumbia, balada, cuarteto cordobés, narcocorridos o música de banda de México. El análisis a profundidad de sus estrategias de sincronización audiovisual de materiales tan heterogéneos nos permitirá conocer a fondo su funcionamiento interno, sus mecanismos lúdicos, sus ganchos de interacción cognitiva y las lecturas paradójicas, intermitentes, reflexivas o discursivas que propician. En el análisis se han empleado herramientas teóricas del análisis del audiovisual, conceptos de los estudios acerca del gesto musical y del análisis de discursos no verbales de naturaleza semiótica con acento en lo social y pragmático. Palabras clave: Internet meme, remix, remezcla digital, música plebeya, videomeme, memética, reciclaje digital musical. Internet memes are cultural units of digital multimedia content that are spread intensely through the network in a process in which they are intervened, remixed, adapted and transformed by their users over and over again. -

Transnational Trajectories of Colombian Cumbia

SPRING 2020 TRANSNATIONAL TRAJECTORIES OF COLOMBIAN CUMBIA Transnational Trajectories of Colombian Cumbia Dr. Lea Ramsdell* Abstract: During 19th and 20th century Latin America, mestizaje, or cultural mixing, prevailed as the source of national identity. Through language, dance, and music, indigenous populations and ethnic groups distinguished themselves from European colonizers. Columbian cumbia, a Latin American folk genre of music and dance, was one such form of cultural expression. Finding its roots in Afro-descendant communities in the 19th century, cumbia’s use of indigenous instruments and catchy rhythm set it apart from other genres. Each village added their own spin to the genre, leaving a wake of individualized ballads, untouched by the music industry. However, cumbia’s influence isn’t isolated to South America. It eventually sauntered into Mexico, crossed the Rio Grande, and soon became a staple in dance halls across the United States. Today, mobile cumbia DJ’s, known as sonideros, broadcast over the internet and radio. By playing cumbia from across the region and sending well-wishes into the microphone, sonideros act as bridges between immigrants and their native communities. Colombian cumbia thus connected and defined a diverse array of national identities as it traveled across the Western hemisphere. Keywords: Latin America, dance, folk, music, cultural exchange, Colombia What interests me as a Latin Americanist are the grassroots modes of expression in marginalized communities that have been simultaneously disdained and embraced by dominant sectors in their quest for a unique national identity. In Latin America, this tension has played out time and again throughout history, beginning with the newly independent republics in the 19th century that sought to carve a national identity for themselves that would set them apart – though not too far apart – from the European colonizers. -

Au Fil De L'eau

Fiche pédagogique Au fil de l’eau Série de 6 courts-métrages Résumés d’animation proposée par le fes- tival Filmar en América Latina : L'eau, source de vie, est au chesses naturelles : la pollution www.filmar.ch centre de ces six courts- des régions exploitées et Versions originales, sans pa- métrages proposés par Filmar en l’appauvrissement des popula- roles ou sous-titrées en français América Latina, festival consacré tions locales. ou espagnol aux cinématographies et à la culture latino-américaines en Chemin d’eau pour un El Galón Suisse. poisson Réal. : Anabel Rodriguez Rios, Les films présentés ont été tour- Une nuit, au cœur d’un quartier Venezuela, 2013, 11’, fiction, nés à Cuba, au Venezuela, en frappé par la pénurie d’eau. V.O., s.-t. français et voice over Colombie et en Bolivie, dans Dans un fond d’eau croupie, un certains cas en coproduction poisson se débat, surveillé par Chemin d’eau pour un poisson avec des pays européens. Dans deux chats. Oscar tente de le Réal. : Mercedes Marro, Colom- bie / France, 2016, 8’, animation, le programme se côtoient films sauver, mais le peu d’eau qu’il V.O. sans paroles d'animation et docu-fictions, possède n’y suffit pas. chaque histoire faisant découvrir C’est alors que l’onde jaillit des Camino del agua des paysages, des modes de vie fontaines ! Aussitôt, tous les Réal. : Carlos Montoya, Colom- et un rapport à l’eau particuliers. habitants quittent leur lit pour bie, 2015, 8’, fiction, V.O., remplir pots, bouteilles et seaux s.-t. -

Spanish 7780.22 Revised 6-15-15.Pdf

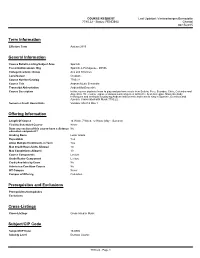

COURSE REQUEST Last Updated: Vankeerbergen,Bernadette 7780.22 - Status: PENDING Chantal 06/15/2015 Term Information Effective Term Autumn 2015 General Information Course Bulletin Listing/Subject Area Spanish Fiscal Unit/Academic Org Spanish & Portuguese - D0596 College/Academic Group Arts and Sciences Level/Career Graduate Course Number/Catalog 7780.22 Course Title Andean Music Ensemble Transcript Abbreviation AndeanMusEnsemble Course Description In this course students learn to play and perform music from Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Colombia and Argentina. The course explores various musical genres within the Andean region. Students study techniques and methods for playing Andean instruments and learn to sing in Spanish, Quechua and Aymara. Cross-listed with Music 7780.22. Semester Credit Hours/Units Variable: Min 0.5 Max 1 Offering Information Length Of Course 14 Week, 7 Week, 12 Week (May + Summer) Flexibly Scheduled Course Never Does any section of this course have a distance No education component? Grading Basis Letter Grade Repeatable Yes Allow Multiple Enrollments in Term Yes Max Credit Hours/Units Allowed 10 Max Completions Allowed 10 Course Components Lecture Grade Roster Component Lecture Credit Available by Exam No Admission Condition Course No Off Campus Never Campus of Offering Columbus Prerequisites and Exclusions Prerequisites/Corequisites Exclusions Cross-Listings Cross-Listings Cross-listed in Music Subject/CIP Code Subject/CIP Code 16.0905 Subsidy Level Doctoral Course 7780.22 - Page 1 COURSE REQUEST Last Updated: Vankeerbergen,Bernadette 7780.22 - Status: PENDING Chantal 06/15/2015 Intended Rank Masters, Doctoral, Professional Requirement/Elective Designation The course is an elective (for this or other units) or is a service course for other units Course Details Course goals or learning • To become familiar with a range of Andean music genres through an applied approach to music performance. -

Cumbia Villera Research Final Report July 10Th 2009

Open Business Models (Latin America) - Phase II Argentina Cumbia Villera Research Final Report IDRC Grant # 112297 Paula Magariños y Carlos Taran for Fundação Getulio Vargas Time period covered: April 20th - July 10th, 2009 July 10th, 2009 Open Business Models (Latin America) - Phase II – Cumbia Villera Final Report – July 10th, 2009 Table of contents I. Synthesis 3 II. Research Problem and General Objectives 5 III. General research design and methodology applied 6 IV. Argentinean Musical Consumptions and CDs sales: General Frame Information 15 V. Cumbia Villera: history, genre scope and evolution, current trends 19 1. Cumbia Villera musical identity: lyrics and sound. Genre features 22 2. Cumbia Villera groups today: current trends 25 VI. Cumbia Villera audience profile and experience 28 1. Who are the consumers? 28 2. Purchase, consumption, and circulation of cumbia 30 3. Cumbia nights 32 4. Los “Bailes”: Dance clubs 34 5. The ball, the dancing party 35 6. The shows 37 7. Some cases 39 8. Concerts at theatres 44 9. Consumers’ expenditures information summary 47 VII. “Movida Tropical” economics, specific characteristics and peculiarities of Cumbia Villera 48 a. The informality issue 50 b.Cumbia Villera economy basics 52 1. The idea: several development paths 54 2. Forming the group: members and investment. First steps. Basic expenses 56 3. Career moment and bailes types: value drivers 58 4. Live shows authors’ rights: key copyright issue 60 5. Recording a disc: independent and mainstream paths 60 6. Diffussion activities: a mutiplataform realm 63 7. Author rights issue and Open Business Model evaluation 65 VIII. Cumbia Villera economics: key actors and activities 67 1. -

Cumbia Villera La Exclusión Como Identidad Luz M. Lardone

Rev. Ciencias Sociales 116: 87-102 / 2007 (II) ISSN: 0482-5276 El “GLAMOUR” dE LA MARGINALIDAD EN ARGENTINA: CUMBIA VILLERA LA EXCLUSIÓN COMO IDENTIDAD Luz M. Lardone* ResuMEN Desde hace algo más de una década, la Argentina es testigo del surgimiento de un nuevo fenómeno musical: la cumbia villera, caracterizado por un ritmo irresistible y letras controversiales. El presente trabajo, investiga la cumbia villera como práctica cultural. Una manifestación discursiva y simbólica territorializada, de la lucha y la respuesta de la vida urbano marginal a las políticas neoliberales en América Latina. Este artículo determina esta práctica cultural como un drama sociopolítico, donde la identidad se construye desde los márgenes. PALABRAS CLAve: ARGENTINA * EXCLusiÓN SOCIAL * cuMBIA VILLerA * IDenTIDAD * PRÁCTicA cuLTurAL * GÉnerO MusicAL * MAniFesTAciÓN siMBÓLicA ABSTRACT For about a decade Argentina has witnessed the emergence of a new musical phenomenon: cumbia villera, characterized by an irresistible rhythm and controversial lyrics. The present work investigates cumbia villera as a cultural practice. A discursive, territorialized symbolic manifestation of the marginal urban life struggle and response to neoliberal policies in Latin America. This paper assesses this cultural practice as a socio-political drama where identity is constructed from the margins. KEY WORDS: ARGENTINA * SOCIAL EXCLusiON * cuMBIA VILLerA * IDenTITY * cuLTurAL PRACTice * MusicAL genres * SYMBOLic MAniFesTATION 1. ESBOZO DE unA PresenTAciÓN DE un o enaltecen desde lo estético y musical; la in- MisMO TODO cuLTurAL terpretan desde lo sociopolítico y económico; la detestan desde el “buen gusto y mejores costum- Mucho se ha hablado y algo se ha escri- bres”; la analizan en un determinado contexto; to sobre la cumbia villera y quienes la cantan y la condenan por representar lo marginal; o la ejecutan.