Feminine the ‘Essentially’ Feminine a Mapping Through Artistic Practice of the Feminine Territory Offered by Early Modern Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio 3 Listings for 12 – 18 June 2010 Page 1

Radio 3 Listings for 12 – 18 June 2010 Page 1 of 11 SATURDAY 12 JUNE 2010 Symphony No.22 in E flat, 'The Philosopher' Tom Service meets conductor Jonathan Nott, principal Amsterdam Bach Soloists conductor of the Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, and talks to SAT 01:00 Through the Night (b00smvg2) tenor Ian Bostridge and director David Alden about performing Jonathan Swain presents rarities, archive and concert recordings 4:35 AM Janacek. Robin Holloway talks about the appeal for from Europe's leading broadcasters Abel, Carl Friedrich (1723-1787) contemporary composers of Schumann's music, plus a report on Sonata No.6 in G major (Op.6 No.6) classical club nights. 1:01 AM Karl Kaiser (transverse flute), Susanne Kaiser (harpsichord) Wagner, Richard (1813-1883) Wie Lachend sie mir Lieder singen ( Tristan und Isolde, Act 1) 4:45 AM SAT 13:00 The Early Music Show (b00sq42f) Brigit Nilsson (Isolde), Irene Dalis (Brangäne), Metropolitan Rore, Cipriano de (c1515-1565) Ghostwriter: The Story of Henri Desmarest Opera Orchestra, Karl Böhm (conductor) Fera gentil The Consort of Musicke, Anthony Rooley (director) Henry Desmarest was obviously a talented musican and 1:10 AM composer, first boy page and then musician in Louis XIV's Wagner, Richard (1813-1883) 4:51 AM court, he began ghost-writing Grands Motets for one of the Amfortas! Die Wunde! (Parsifal, Act 1) Berlioz, Hector (1803-1869) chapel directors Nicholas Goupillet when he was in his early Jon Vickers (Parsifal), Christa Ludwig (Kundry), Metropolitan Le Carnaval romain - overture (Op.9) twenties. -

APPENDIX 1 Inventories of Sources of English Solo Lute Music

408/2 APPENDIX 1 Inventories of sources of English solo lute music Editorial Policy................................................................279 408/2.............................................................................282 2764(2) ..........................................................................290 4900..............................................................................294 6402..............................................................................296 31392 ............................................................................298 41498 ............................................................................305 60577 ............................................................................306 Andrea............................................................................308 Ballet.............................................................................310 Barley 1596.....................................................................318 Board .............................................................................321 Brogyntyn.......................................................................337 Cosens...........................................................................342 Dallis.............................................................................349 Danyel 1606....................................................................364 Dd.2.11..........................................................................365 Dd.3.18..........................................................................385 -

Mönster Och Möjligheter Programblad 2

Mönster och möjligheter Genus och gestaltning i 1700-talsopera Operahögskolan/Stockholms konstnärliga högskola, 20 september 2018 Ett gästspel från Musikhögskolan vid Luleå tekniska universitet, i Piteå och Högskolan för scen och musik, Göteborgs universitet Medverkande På scen: Tove Dahlberg, alla roller Bo Wannefors, piano Idé, manus, och iscensättning: Tove Dahlberg och Kristina Hagström-Ståhl Ljusdesign: Tobias Hagström-Ståhl/Lumination of Sweden Övriga pianister: Eric Skarby, Tommy Jonsson, Rut Pergament Coach, maskulinitet: Eva Johansson * * * Hur kan genusforskning och kritiska perspektiv användas i en konstnärlig praktik? Vilka är möjligheterna att arbeta normkritiskt – och normkreativt – med opera? I det här proJektet undersöker Tove Dahlberg och Kristina Hagström-Ståhl tillsammans sångarens handlingsutrymme i den konstnärliga processen, samt relationen mellan scenisk och musikalisk gestaltning i operarepertoar. Med Mozarts opera Figaros bröllop (1786) som utgångspunkt och material har Tove och Kristina mötts i en serie laborationer, som syftat till att väcka frågor kring konventioner och ”tyst kunskap” inom opera, men även att utveckla metoder för breddade och medvetna val i den konstnärliga processen. Med sig har de haft pianister med lång erfarenhet av att arbeta med Mozarts operor. Tove tar sig an fem kvinnliga och manliga roller ur operan, med en dubbel målsättning: att utmana sina egna vokala och sceniska register och att låta operans scener och arior bli föremål för konstnärlig undersökning. Särskilt har vi tittat på hur sångliga och kroppsliga praktiker tillsammans påverkar hur maskulinitet och femininitet kan gestaltas och hur gestaltningen blir läsbar för en publik. En genomgående frågeställning har gällt relationen mellan operan som material och konstnärligt verk i egen rätt – mellan sångarens och rollens behov. -

Download Booklet

This is a record from the Golden Age in England, the age of Shakespeare. Most things in England seem to have flourished for some decades about 1600 ; even music. This was the age of the lutenists and the virginalists. Madrigals were sung around a ci.rculu table at home and majestic music accompanied the sewices in the great cathedrals. It was at this time l}]'at the ayre, the solo song with lute accompmiment, was at its peak. Numerous composers sought the ideal maniage of word and music' Richard Barnfield brought together two of the period's greatest nmes, the poet Edmund Spenser and the musician John Dowland in a sonet : (see text I) The first printed volume of solo songs appeaed in 1597 : (see text II) The universities were, of course. Oxford and Cambridge. The particular "notation" used by lute players is known as tablature. The coliection was pdnted in such a manner that the songs could be performed by a single voice with lute accompaniment or as four-part songs, The latter could be achieved by sitting in a circle round the music wtrich is arranged on the page with one part at each point of the compas. A contemporary wrote that it would be as well always to follow this pattern fot other- wise the pdtsingers would have to look over someone's shoulder and would improv- ise their own unfortunate counterparts. In 1597, the year of publication, JOHN DOWLAND was 34' He abeadv had a good deal to say about his life in the preface to the Coudeous Reader : (see text III) Exactly ! The golden age of English music was subiect to powerful impulses from abroad, not least from ltaly. -

Night's Black Bird Airs, Arias, Madrigals, and Tonos

Bass Viola da Gamba Seven-string bass viola da gamba made by Dominik Zuchowics in 1997. The instrument is based on a six-string Guest Artist Series 2017–2018 Season English viol built by Richard Meares (ca. 1680). The back and sides are Sara M. Snell Music Theater Wednesday, March 21, 7:30 PM constructed of flamed maple and the top is spruce. The instrument is a hybrid featuring an English body, French neck with an added seventh string, and a Night’s Black Bird German lion’s head, which adorns the carved pegbox. Airs, Arias, Madrigals, and Tonos Lute Eight-course lute made by Richard Fletcher in 1998. The lute is based on a Bolognese instrument built by Laux Maler (ca. 1540). The bowl consists of eleven flamed maple ribs. The neck and pegbox are veneered with ebony and the top is European spruce. The rosette is carved by hand into the spruce top. Baroque Guitar The cypress curtain of the night Thomas Campion Five-course Baroque guitar built by (1567–1620) Gabriel Aguilera Valdebenito in 2015. The instrument is based on a five-course Cremonan guitar built by Antonio Flow, my tears John Dowland Stradivari (ca. 1700). The back and (c. 1562–1626) sides are constructed of walnut. The neck is veneered with ebony and the top is European spruce. The rosette is carved pearwood and the moustachios are Think’st thou then by thy feigning John Dowland ebony. What, then, is love but mourning Philip Rosseter (1568–1623) Night’s Black Bird Divisions on Never weather-beaten sail Thomas Campion Elizabeth Conner, Bass Viola da Gamba, received her Bachelor of Music in Double Bass Performance at New England Conservatory and her Masters of Music in Double Bass Performance at the University of Michigan. -

Opera Bands and Artists List

Opera Bands and Artists List Szeged Symphony https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/szeged-symphony-orchestra-265888/albums Orchestra Marek Torzewski https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/marek-torzewski-11768532/albums Frederic Toulmouche https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/frederic-toulmouche-20001877/albums Dominique Girod https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/dominique-girod-16056863/albums Livia Budaï-Batky https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/livia-buda%C3%AF-batky-26988123/albums Vitaliy Kil'chevskiy https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/vitaliy-kil%27chevskiy-19850392/albums Yaniv D'Or https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/yaniv-d%27or-16131484/albums Malvīne Vīgnere- https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/malv%C4%ABne-v%C4%ABgnere-gr%C4%ABnberga- Grīnberga 16363082/albums Rosa Rimoch https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/rosa-rimoch-29419597/albums Karine Babajanyan https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/karine-babajanyan-18628035/albums Jean-Baptiste Mathieu https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/jean-baptiste-mathieu-11927434/albums Opera Las Vegas https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/opera-las-vegas-16960608/albums Vicente Forte https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/vicente-forte-11954634/albums Albert Lim https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/albert-lim-23887792/albums Alban Berg https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/alban-berg-78475/albums Bedřich Diviš Weber https://www.listvote.com/lists/music/artists/bed%C5%99ich-divi%C5%A1-weber-79023/albums -

Mass in C Minor Performances of Two Academy of St Martin Fine Choral Works from in the Fields Two Masters of the Baroque Era

CORO CORO Vivaldi: Gloria in D Fauré: Requiem Bach: Magnificat in D Mozart: Vespers Harry Christophers Elin Manahan Thomas MOZART The Sixteen Roderick Williams Harry Christophers Resounding The Sixteen Mass in C minor performances of two Academy of St Martin fine choral works from in the Fields two masters of the Baroque era. “…the sense of an ecstatic movement towards cor16057 cor16042 cor16057 Paradise is tangible.” the times Handel: Messiah Barber: Agnus Dei 3 CDs (Special Edition) An American Collection Carolyn Sampson Barber, Bernstein, Catherine Wyn-Rogers Copland, Fine, Reich, Mark Padmore del Tredici Christopher Purves “The Sixteen are, as “…this inspiriting new usual, in excellent form performance becomes here. Recording and a first choice.” remastering are top- notch.” Gillian Keith the daily telegraph notch.” cor16062 cor16031 american record guide Tove Dahlberg Harry Christophers Thomas Cooley To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs visit Handel and Haydn Society Nathan Berg www.thesixteen.com cor16084 ne of the many delights of being of your seat” suspense that one feels in the exquisite ‘Et incarnatus est’ and it OArtistic Director of America’s is well worth that risk. One can never achieve this degree of concentration and oldest continuously performing arts total immersion in the music whilst in the recording studio; whatever mood is organization, the Handel and Haydn set, subconsciously we always know we can have another go at it. Society, is that I am given the opportunity to present most of our concert season at I feel very privileged to take this august Society towards its Bicentennial; yes, the Handel and Haydn Society was founded in 1815. -

Olli Kortekangas' Opera Premiere Sven-David Sandström at 75

NORDIC HIGHLIGHTS 3/2017 NEWSLETTER FROM GEHRMANS MUSIKFÖRLAG & FENNICA GEHRMAN Olli Kortekangas’ opera premiere Sven-David Sandström at 75 NEWS Angela Hewitt Edicson Ruiz’s 25th to premiere Whittall performance Angela Hewitt is to be the soloist on 5 It will be his 25th perfor- October in the world premiere in Ottawa, mance, when Edicson Canada, of the piano concerto Nameless Ruiz gives the German Seas by Matthew Whittall. Conducting premiere of Rolf Mar- the National Arts Centre Orchestra will tinsson’s Double Bass Con- be Hannu Lintu. The performance is certo with the Deutsche part of the ‘Ideas of North’ festival cel- Radiophilharmonie Saa- ebrating Canada’s 150th and Finland’s rbrücken Kaiserslauten 100th birthdays. The Lapland Chamber in June of next year. The Orchestra will also be part of the pro- Australian premiere took gramme, with Kalevi Aho’s 14th sym- place last April with the phony Rituals . Queensland Symphony The Whittall concerto was commis- Orchestra, and Novem- sioned jointly by PianoEspoo Festival and ber will see the Chi- the National Arts Centre Corporation. nese premiere with the The Finnish premiere is scheduled on Hong Kong Sinfonietta. OLIVEROS NOHELY PHOTO: 10 November by the Finnish Radio Ruiz has performed the concerto earlier with orchestras in Symphony Orchestra with Risto-Matti Venezuela, Japan, Taiwan, Sweden, Spain, Austria, France and PHOTO: PETER SEARLE PETER PHOTO: Marin as the soloist. Hungary. Tango solo on stage Colourstrings in Apple iBook Store Soprano Marika Krook and a chamber ensemble Colourstrings goes digital! The Violin and Cello ABC books are from Stockholm are to perform the monologue now available as digital publications in the Apple iBook Store. -

Hors Série Saison 12 / 13

accentus hors série saison 12 / 13 accentus jeune chœur paris tenso ..................................................................................................... éducation recherche développement artistique hors série 2012/2013 Lettre d’information d’ accentus Directeur de publication Nicolas Droin Rédactrice en chef Anaïs Humez Rédaction Antoine Pecqueur Photos Julio Villani Conception graphique composite (composite-agence.fr) Impression Imprimerie Frazier n° ISSN en cours / Programmes et informations donnés sous réserve de modifications Exemplaire gratuit ÉDITO UNE SAISON RICHE EN NOUVELLES AVENTURES Cette saison, les premières s’enchaînent pour accentus. À l’automne, Laurence Equilbey va diriger pour la première fois au Palais Garnier. À l’affiche : une création chorégraphique de Marie-Agnès Gillot, danseuse étoile du Ballet de l’Opéra de Paris, sur des musiques de Bruckner, Ligeti et Feldman – une dramaturgie musicale signée Laurence Equilbey. accentus va également participer au premier concert d’Insula orchestra. Le nouvel orchestre sur instruments anciens fondé par Laurence Equilbey fait effectivement son entrée dans la structure erda I accentus. Soutenue par le Conseil général des Hauts-de-Seine, cette formation promet de revisiter l’époque classique et pré-romantique, tant dans le répertoire symphonique que dans l’oratorio (voir brochure spécifique). La saison est également rythmée par des créations particulièrement attendues. Bruno Mantovani livre sa Cantate n°4, dans laquelle il confronte le chœur à deux instruments : le violoncelle de Sonia Wieder-Atherton et l’accordéon de Pascal Contet. Dans le domaine lyrique, accentus participe, à l’Opéra de Rouen Haute-Normandie, à la création d’un opéra du compositeur belge Michel Fourgon inspiré du destin de… Lolo Ferrari. Une première sulfureuse ! On peut également parler de premières pour certains ouvrages du passé exhumés de l’oubli. -

Lsm11-6 Ayout

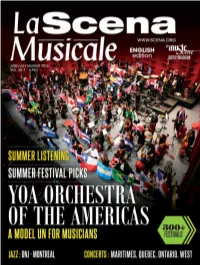

sm20-7_EN_p01_coverV2_sm20-1_BI_pXX 15-06-03 12:55 PM Page 1 RCM_LaScenaMusicale_4c_fp_June+Aug15.qxp_Layoutsm20-7_EN_p02_rcmAD_sm20-1_BI_pXX 15-06-03 12:56 1 2015-05-27PM Page 2 9:33 AM Page 1 2015.16 Terence CONCERT Blanchard SEASON More than 85 classical, jazz, pop, world music, and family concerts to choose from! Koerner Hall / Mazzoleni Concert Hall / Conservatory Theatre Igudesman & Joo Daniel Hope Vilde Frang Jan Lisiecki SUBSCRIPTIONS ON SALE 10AM FRIDAY JUNE 12 SINGLE TICKETS ON SALE 10AM FRIDAY JUNE 19 416.408.0208 www.performance.rcmusic.ca 273 BLOOR STREET WEST (BLOOR ST. & AVENUE RD.) TORONTO sm20-7_EN_p03_torontosummerAD_sm20-1_BI_pXX 15-06-03 12:57 PM Page 3 CELEBRATING 10 YEARS JUL 16-AUG 9 DANISH STRING KARITA MATTILA QUARTET GARRICK AMERICAN OHLSSON AVANT-GARDE DANILO YOA ORCHESTRA OF THE AMERICAS PÉREZ WITH INGRID FLITER AND MUCH MORE! UNDER 35 YEARS OLD? TICKETS ONLY $20! TORONTOSUMMERMUSIC.COM 416-408-0208 an Ontario government agency un organisme du gouvernement de l’Ontario sm20-7_EN_p04_TOC_sm20-1_BI_pXX 15-06-03 12:58 PM Page 4 VOL 20-7 JUNE/JULY/AUGUST 2015 CONTENTS 10 INDUSTRY NEWS 11 Orchestre National de Jazz - Montréal 12 Jazz Festival Picks 14 Classical Festival Picks 19 Arts Festival Picks 21 Summer Listening GUIDES 22 Canadian Summer Festivals 37 REGIONAL CALENDAR 38 CONCERT PREVIEWS YOA ORCHESTRA OF THE AMERICAS 6 FOUNDING EDITORS PUBLISHER OFFICE MANAGER TRANSLATORS SUBSCRIPTIONS Wah Keung Chan, Philip Anson Wah Keung Chan Brigitte Objois Michèle Duguay, Véronique Frenette, Surface mail subscriptions (Canada) cost EDITOR-IN-CHIEF SUBSCRIPTIONS & DISTRIBUTION Cecilia Grayson, Eric Legault, $33/ yr (taxes included) to cover postage and La Scena Musicale VOL. -

Coronation Mass

CORO CORO Mozart: Mass in C minor Harry Christophers & Handel and Haydn Society MOZART Gillian Keith, Tove Dahlberg, Thomas Cooley, Nathan Berg Coronation Mass “…a commanding and compelling reading of an important if often overlooked monument in Mozart’s musical development.” cor16084 gramophone recommended Mozart: Requiem Harry Christophers & Handel and Haydn Society Elizabeth Watts, Phyllis Pancella, Andrew Kennedy, Eric Owens “A requiem full of life…Mozart’s final masterpiece has never sounded so exciting.” classic fm magazine Teresa Wakim cor16093 Paula Murrihy Harry Christophers Thomas Cooley To find out more about CORO and to buy CDs visit Handel and Haydn Society Sumner Thompson www.thesixteen.com cor16104 ne of the many delights of being I feel very privileged to take this august Society towards its Bicentennial; yes, the OArtistic Director of America's oldest Handel and Haydn Society was founded in 1815. Handel was the old, Haydn the new continuously performing arts organisation, the (he had just died in 1809), and what we can do is continue to perform the music of the Handel and Haydn Society, is that I am given past but strip away the cobwebs and reveal it anew. This recording of music by Haydn the opportunity to present most of our concert and Mozart was made possible by individuals who are inspired by the work of the season at Boston's glorious Symphony Hall. Built Handel and Haydn Society. Our sincere thanks go to all of them. in 1900, it is principally the home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, but it has been our primary Borggreve Marco Photograph: performance home since 1900 as well, and it is considered by many, with some justification I would add, to be one of the finest concert halls in the world. -

Records Ofearfv~ English Drama

:I'M! - 1982 :1 r P" A newsletter published by University of Toronto Press in association with Erindale College, University of Toronto and Manchester University Press . JoAnna Dutka, editor Records ofEarfv~ English Drama The biennial bibliography of books and articles on records of drama and minstrelsy contributed by Ian Lancashire (Erindale College, University of Toronto) begins this issue ; John Coldewey (University of Washington) discusses records of waits in Nottinghamshire and what the activities of the waits there suggest to historians of drama ; David Mills (University of Liverpool) presents new information on the iden- tity of Edward Gregory, believed to be the scribe of the Huntington manuscript of the Chester cycle. IAN LANCASHIRE Annotated bibliography of printed records of early British drama and minstrelsy for 1980-81 This list, covering publications up to 1982 that concern documentary or material records of performers and performance, is based on a wide search of recent books, periodicals, and record series publishing evidence of pre-18th-century British history, literature, and archaeology . Some remarkable achievements have appeared in these years. Let me mention seven, in the areas of material remains, civic and town records, household papers, and biography . Brian Hope-Taylor's long-awaited report on the excavations at Yeavering, Northumberland, establishes the existence of a 7th-century theatre modelled on Roman structures . R.W. Ingram has turned out an edition of the Coventry records for REED that discovers rich evidence from both original and antiquarian papers, more than we dared hope from a city so damaged by fire and war. The Malone Society edition of the Norfolk and Suffolk records by David Galloway and John Wasson is an achievement of a different sort : the collection of evidence from 41 towns has presented them unusual editorial problems, in the solv- ing of which both editors and General Editor Richard Proudfoot have earned our gratitude .