A Kötet Nyomdakész November11

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ess4 - 2008 Documentation Report

ESS4 - 2008 DOCUMENTATION REPORT THE ESS DATA ARCHIVE Edition 5.5 Version Notes, ESS4 - 2008 Documentation Report ESS4 edition 5.5 (published 01.12.18): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.5. Changes from edition 5.4: Czechia: Country name changed from Czech Republic to Czechia in accordance with change in ISO 3166 standard. 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS4 ed. 4.5 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed. 4.5 data. Israel: 46 Deviations amended. Deviation in F1-F4 (HHMMB, GNDR-GNDRN, YRBRN-YRBRNN, RSHIP2-RSHIPN) added. Appendix: Appendix A3 Variables and Questions and Appendix A4 Variable lists have been replaced with Appendix A3 Codebook. ESS4 edition 5.4 (published 01.12.16): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.4. Changes from edition 5.3: 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.4 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.4 data. Slovenia: 46 Deviations. Amended. Deviation in B15 (WRKORG) added. Appendix: A2 Classifications and Coding standards amended for EISCED. A3 Variables and Questions amended for EISCED, WRKORG. Documents: Education Upgrade ESS1-4 amended for EISCED. ESS4 edition 5.3 (published 26.11.14): Applies to datafile ESS4 edition 4.3 Changes from edition 5.2: All links to the ESS Website have been updated. 21 Weighting: Information regarding post-stratification weights updated. 25 Version notes: Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.3 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS4 ed.4.3 data. Lithuania: ESS4 - 2008 Documentation Report Edition 5.5 2 46 Deviations. -

Comparative European Party Systems

COMPARATIVE EUROPEAN PARTY SYSTEMS Comparative European Party Systems, Second Edition, provides a comprehensive analysis across 48 party systems of party competition, electoral systems and their effects, and the classification of party systems and governments from 1945 through late-2018. The book consists of three parts. Part I provides a comparative and quantitative overview of party systems according to party families, patterns of party competition, electoral systems and their effects, and classification of party systems and governments. Part II consists of 38 detailed country profiles of longstanding democracies and of the European Union (plus nine profiles on regions such as in Spain and the UK), providing essential detail on the electoral systems, parties, party patterns and systems, dimensions of political competition, and governments. Part III provides an analysis of 10 additional country profiles of oscillating regimes such as Russia, Ukraine, and Balkan and Transcaucasus states. Comparative European Party Systems provides an excellent overview of topical issues in comparative election and party system research and presents a wealth of information and quantitative data. It is a crucial reference for scholars and students of European and comparative politics, elections, electoral systems, and parties and party systems. Alan Siaroff is Professor of Political Science at the University of Lethbridge, Canada. COMPARATIVE EUROPEAN PARTY SYSTEMS An Analysis of Parliamentary Elections Since 1945 Second Edition Alan Siaroff Second edition published 2019 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN and by Routledge 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2019 Alan Siaroff The right of Alan Siaroff to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. -

The Case of Bulgaria's Nuclear Energy Sector

ISSN 2029-4581. ORGANIZATIONS AND MARKETS IN EMERGING ECONOMIES, 2015, VOL. 6, No. 2(12) DETERMINANTS OF SOVEREIGN INVESTMENT PROTECTIONISM: THE CASE OF BULGARIA’S NUCLEAR ENERGY SECTOR Elena A. Iankova * Cornell University Atanas G. Tzenev Binghamton University Abstract . Foreign direct investment (FDI) by entities controlled by foreign governments (especially state-owned enterprises) is a new global phenomenon that is most o!en linked to the rise of emerging markets such as China and Russia. Host governments have struggled to properly react to this type of investment activity especially in key strategic sectors and critical in"astructure that ultimately raise questions of national security. Academic research on sovereign investment as a factor contributing to the new global protectionist trend is very limited, and predominantly focused on sovereign investors "om China. #is study explores the speci$cs of Russian sovereign investment in the former Soviet Bloc countries, now members of the European Union, especially in strategic sectors such as energy. We use the case of Bulgaria’s nuclear energy sector and the involvement of Russia’s state-owned company Rosatom in the halted Belene nuclear power plant project to analyze the dynamics of policy and politics, political-economic ideologies and historical legacies in the formation of national stances towards Russia as a sovereign investor. Our research contributes to the emerging literature on FDI protectionism and sovereign investment by emphasizing the signi$cance of political-ideological divides and the heritage of the past as determinants of sovereign investment protectionism. Key words : foreign direct investment policy; state-controlled entities; national security; nuclear energy, post-communist countries. -

May 2009 May 2009

May 2009 May 2009 SUMMARY SUMMARY I. INTRODUCTION: A GENERAL PERSPECTIVE 2 I. INTRODUCTION: A GENERAL PERSPECTIVE 2 II. BULGARIA IN THE EUROPEAN UNION: THE CHALLENGE OF II. BULGARIA IN THE EUROPEAN UNION: THE CHALLENGE OF RESPONSIBILITY 9 RESPONSIBILITY 9 II.1. BULGARIA IN THE EUROPEAN UNION: The road towards accession II.1. BULGARIA IN THE EUROPEAN UNION: The road towards accession II.2. JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS: The heart of the crisis II.2. JUSTICE AND HOME AFFAIRS: The heart of the crisis II.3. THE WEAKNESS OF THE BULGARIAN ADMINISTRATION: Overcoming the II.3. THE WEAKNESS OF THE BULGARIAN ADMINISTRATION: Overcoming the lack of administrative capacity lack of administrative capacity III. THE EUROPEAN UNION AND BULGARIA: A TEST FOR EUROPEAN III. THE EUROPEAN UNION AND BULGARIA: A TEST FOR EUROPEAN SOLIDARITY 55 SOLIDARITY 55 III.1. THE SUSPENSION OF EU FUNDS TO BULGARIA: An unprecedented III.1. THE SUSPENSION OF EU FUNDS TO BULGARIA: An unprecedented decision decision III.2. THE MISMANAGEMENT OF EU FUNDS: To preserve European solidarity III.2. THE MISMANAGEMENT OF EU FUNDS: To preserve European solidarity III.3. ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL REFORMS: Achieving European living standards III.3. ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL REFORMS: Achieving European living standards IV. BUILDING A DYNAMIC PARTNERSHIP 77 IV. BUILDING A DYNAMIC PARTNERSHIP 77 IV.1. STRENGHTENING DIALOGUE: Enhanced cooperation between the European IV.1. STRENGHTENING DIALOGUE: Enhanced cooperation between the European Commission, Member States and the Bulgarian government Commission, Member States and the Bulgarian government IV.2. BULGARIA IN THE EU: Setting up a national European agenda IV.2. -

Explaining Religious Change in Medieval and Early Modern Europe

a Migrations of the Holy: Explaining Religious Change in Medieval and Early Modern Europe Alexandra Walsham University of Cambridge Cambridge, United Kingdom How do we conceptualize and explain religious change in medieval and early modern Europe without perpetuating distorting paradigms inherited from the very era of the past that is the subject of our study? How can we do justice to historical development over time without resorting to linear grand narratives that have their intellectual origins in the very movements that we seek to comprehend? In one way or another, this challenging question has inspired all my published work to date, which has focused on the ways in which early mod- ern society adapted to the religious revolutions that unfolded before it. My work has explored the ambiguities, anomalies, and ironies that accompany dramatic moments of ideological and cultural rupture. It has sought to bal- ance recognition of the decisive transformations wrought by the Protestant and Catholic Reformations with awareness of the complexities and contra- dictions that characterized their evolution and entrenchment in practice. It has been marked by a consuming interest in the currents of continuity that tempered, mediated, and even facilitated the upheavals of the early mod- ern era. One consequence of this preoccupation with analyzing how and why cultures are held in tension and suspension during critical phases of transition is that I have been very much less effective in acknowledging and accounting for religious change itself. This is my Achilles’ heel as a historian, and one that I share with a number of other historians of my generation. -

2011 Bulgarian Media Monitoring

LESS FREEDOM, MORE CONFLICTS: 2011 BULGARIAN MEDIA MONITORING ||||||| ANNUAL REPORT OF FOUNDATION MEDIA DEMOCRACY ||||||| IN COOPERATION WITH MEDIA PROGRAM SOUTH EAST EUROPE KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG Sofia, 2012 Translated by Katerina Popova 2 Contents Introduction: On This Report and Its Context Orlin Spassov 5 Georgi Lozanov Media Regulation: Effects and Deficiencies 9 Todor P. Todorv Television in Bulgaria in 2011: Problems and Trends 15 Georgi Savchev Media on the Eve of Doomsday: Bulgarian Radio in 2011 20 Orlin Spassov Attitudes Towards Politicians and Institutions in the Bulgarian Press in 2011: A Look at Seven National Dailies 24 Bogdana Dencheva The Year of Tabloids Balgaria Dnes and Vseki Den Seven Months On: A Brief Retrospective 33 Elena Koleva 2011 Through the Lens of Press Photography 37 Silvia Petrova The Lifestyle Press: Back to Tradition 44 Gergana Kutseva (Non)Uses of Freedom 48 Nikoleta Daskalova Political Content on News Sites: Status Quo Proves Hard to Change 53 3 Maya Tsaneva 2011: A Little of the European Union, Lots of Bulgaria 60 Petko Karadechev Electrical Storm, or, How Some English-Language Media Saw Bulgaria’s Big Energy Projects in 2011 64 Vasilena Yordanova WikiLeaks on Bulgarian Politics 69 Eli Alexandrova Facebook 2011: Elections in Troubled Times 72 Marina Kirova How Politicians and Citizens Failed to Meet on the Web in 2011 75 Julia Rone Videopolitics: My Family and Other Animals 80 Kalina Petkova Non-Political Content in the Bulgarian Media in 2011 88 Appendix Market Links Research and Consulting Agency Media Index: Media Monitoring 92 4 Introduction: On This Report and Its Context The 2011 annual report of Foundation Media Democracy (FMD) was produced by a team from the Media Monitoring Lab (MML). -

Ess3 - 2006 Documentation Report

ESS3 - 2006 DOCUMENTATION REPORT THE ESS DATA ARCHIVE Edition 3.7 Version Notes, ESS3 - 2006 Documentation Report ESS3 edition 3.7 (published 01.12.18): Applies to datafile ESS3 edition 3.7. Changes from edition 3.6: 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS1 ed. 3.7 data. Appendix: Appendix A3 Variables and Questions and Appendix A4 Variable lists has been replaced with Appendix A3 Codebook. ESS3 edition 3.6 (published 01.12.16): Applies to datafile ESS3 edition 3.6. Changes from edition 3.5: 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS3 ed.3.6 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS3 ed.3.6 data. Slovenia: 46 Deviations. Amended. Deviation in B15 (WRKORG) added. Appendix: A2 Classifications and Coding standards amended for EISCED. A3 Variables and Questions amended for EISCED, WRKORG. Documents: Education Upgrade ESS1-4 amended for EISCED. ESS3 edition 3.5 (published 26.11.14): Applies to datafile ESS3 edition 3.5 Changes from edition 3.4: All links to the ESS Website have been updated. 21 Weighting. Information updated to include post-stratification weights. 25 Version notes. Information updated for ESS3 ed.3.5 data. 26 Completeness of collection stored. Information updated for ESS3 ed.3.5 data. Belgium: 46 Deviations. Deviation added on respondents below lower age cut-off (AGEA). Great Britain: 46 Deviations. D3 (LVPNTYR) ambigous code "0" could mean "Still in parental home, never left 2 months" or no answer. Latvia: 46 Deviations. No Post Post-stratification weights (PSPWGHT) added. ESS3 - 2006 Documentation Report Edition 3.7 2 Romania: 46 Deviations. -

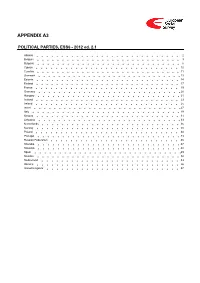

ESS6 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS6 - 2012 ed. 2.1 Albania 2 Belgium 3 Bulgaria 6 Cyprus 10 Czechia 11 Denmark 13 Estonia 14 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Israel 27 Italy 29 Kosovo 31 Lithuania 33 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 43 Russian Federation 45 Slovakia 47 Slovenia 48 Spain 49 Sweden 52 Switzerland 53 Ukraine 56 United Kingdom 57 Albania 1. Political parties Language used in data file: Albanian Year of last election: 2009 Official party names, English 1. Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë (PS) - The Socialist Party of Albania - 40,85 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Partia Demokratike e Shqipërisë (PD) - The Democratic Party of Albania - 40,18 % election: 3. Lëvizja Socialiste për Integrim (LSI) - The Socialist Movement for Integration - 4,85 % 4. Partia Republikane e Shqipërisë (PR) - The Republican Party of Albania - 2,11 % 5. Partia Socialdemokrate e Shqipërisë (PSD) - The Social Democratic Party of Albania - 1,76 % 6. Partia Drejtësi, Integrim dhe Unitet (PDIU) - The Party for Justice, Integration and Unity - 0,95 % 7. Partia Bashkimi për të Drejtat e Njeriut (PBDNJ) - The Unity for Human Rights Party - 1,19 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Socialist Party of Albania (Albanian: Partia Socialiste e Shqipërisë), is a social- above democratic political party in Albania; it is the leading opposition party in Albania. It seated 66 MPs in the 2009 Albanian parliament (out of a total of 140). It achieved power in 1997 after a political crisis and governmental realignment. In the 2001 General Election it secured 73 seats in the Parliament, which enabled it to form the Government. -

DAVID MAYES Department of History Sam Houston State University Box

DAVID MAYES Department of History Phone: 936.294.1485 Sam Houston State University Fax: 936.294.3938 Box 2239 Email: [email protected] Huntsville, TX 77341-2239 EDUCATION Ph.D., 2002 University of Wisconsin-Madison M.A., 1996 University of Richmond B.A., 1994 University of Richmond 2002-2003 Postdoctoral Fellow. Institut für Europäische Geschichte. Mainz, Germany 2002 Studies at the Historisches Institut. Universität Bern, Switzerland 2000-2001 Language study, residence. Lausanne, Switzerland 1998-2000 Archival research: Marburg, Kassel, Darmstadt. Philipps-Universität Marburg, Germany 1998 Language study. Universität Regensburg, Germany 1996 Language study. Alliance Française, Paris, France 1995, 1996 Language study. Goethe Institut, Germany (Schwäbisch Hall, Prien, Staufen) 1993 Courses in 19th-century British History & Literature. Oxford University, England ACADEMIC APPOINTMENTS Sam Houston State University, Department of History Interim Chair, 2015-16 Assistant Chair, 2011-15 Associate Professor, 2009- Assistant Professor, 2004-2009 University of Montana, Adjunct Assistant Professor 2003-2004 University of Richmond, Lecturer, Fall 1999 FELLOWSHIPS 2015 Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst. Research Stay for University Academics. 2013 National Endowment for the Humanities, Summer Seminar. Grand Rapids, Michigan. Faculty Development Leave (SHSU) 2006-2007 Enhancement Grant for Professional Development (SHSU) 2002-2003 Postdoktorand-stipendium, Institut für Europäische Geschichte. Mainz, Germany. 2000 Fulbright Grant Renewal 1998-1999 Fulbright Commission Grant. Affiliation: Philipps-Universität Marburg, Germany. 1998 Center for Reformation Research Grant. Saint Louis, Missouri. Mayes / Curriculum Vitae 2 BOOK Communal Christianity: The Life & Loss of a Peasant Vision in Early Modern Germany. Studies in Central European Histories, vol. 35. Editors Thomas A. Brady Jr. & Roger Chickering. Boston: Brill Academic Publishers, 2004. -

|||GET||| an Interpretation of Religion Human Responses to The

AN INTERPRETATION OF RELIGION HUMAN RESPONSES TO THE TRANSCENDENT, SECOND EDITION 2ND EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE John Hick | 9780300106688 | | | | | An Interpretation of Religion: Human Responses to the Transcendent / Edition 2 In philosophical theologyhe made contributions in the areas of theodicyeschatologyand Christologyand in the philosophy of religion he contributed to the areas of epistemology of religion and religious pluralism. That is, in attributing omniscience to God, would one thereby claim God knows all truths in a way that is analogous to the way we come to know truths about the world? The theory has formidable critics and defenders. Written with great clarity and force, and with a wealth of fresh insights, this major work based on the author's Gifford Lectures of treats the principal topics in the philosophy of religion and establishes both a basis for religious affirmation today and a framework for the developing world-wide inter-faith dialogue. A major advocate of this new turn is John Caputo. Perhaps one of the reasons why philosophy of religion is often the first topic in textbook introductions to philosophy is that this is one way to propose to readers that philosophical study can impact what large numbers of people actually think about life and value. It has been argued that Hick has secured not the equal acceptability of diverse religions but rather their unacceptability. For a discussion of these objections and replies and references, see Taliaferro Mackie, J. According to Bultmann, when we ask the question of the meaning -

Proquest Dissertations

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis arxf dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while otfiers may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, ookxed or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleodthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the autftor did rx>t send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unautfxxized copyright material had to be removed, a note will irKficate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9” black and white photographic prints are availat)le for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Artwr, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 UMT PROBLEMS OF DEMOCRATIC TRANSITION AND CONSOLIDATION IN POST-COMMUNIST BULGARIA DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Rossen V. Vassilev, M.A. The Ohio State University 2000 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Gunther, Adviser Approved by Professor Anthony Mughan Professor Goldie Shabad Adviser Department of Political Science UMI Number 9971652 UMI UMI Microform9971652 Copyright 2000 by Bell & Howell Information and Leaming Company. -

Multicultural Education: Issues and Perspectives

Banks-ffirs.indd 2 9/4/2015 8:57:18 PM Multicultural Education Banks-ffirs.indd 1 9/4/2015 8:57:18 PM Banks-ffirs.indd 2 9/4/2015 8:57:18 PM Multicultural Education ISSUES AND PERSPECTIVES Ninth Edition Edited by James A . Banks University of Washington , Seattle Cherry A . McGee Banks University of Washington , Bothell Banks-ffirs.indd 3 9/4/2015 8:57:18 PM Vice President & Director George Hoffman Executive Editor Christopher Johnson Assistant Wauntao Matthews Senior Director Don Fowley Project Manager Gladys Soto Project Specialist Nichole Urban Project Assistant Anna Melhorn Assistant Marketing Manager Puja Katariwala Associate Director Kevin Holm Production Editor Janani Dilip Rogger Photo Researcher Billy Ray Cover Photo Credit © Maynard Johnny Jr./GarfinkelPublication Inc. This book was set in 10/12 Times LT Std by SPi Global and printed and bound by Lightning Source Inc. Founded in 1807, John Wiley & Sons, Inc. has been a valued source of knowledge and understanding for more than 200 years, helping people around the world meet their needs and fulfill their aspirations. Our company is built on a foundation of principles that include responsibility to the communities we serve and where we live and work. In 2008, we launched a Corporate Citizenship Initiative, a global effort to address the environmental, social, economic, and ethical challenges we face in our business. Among the issues we are addressing are carbon impact, paper specifications and procurement, ethical conduct within our business and among our vendors, and community and charitable support. For more information, please visit our website: www.wiley.com/go/citizenship.