Antibiotic Susceptibility Evaluation of Group a Streptococcus Isolated

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BBL Group a Selective Strep Agar with 5% Sheep Blood (Ssa )

BBL™ Group A Selective Strep Agar with 5% Sheep Blood (ssA™) and ! BBL™ Trypticase™ Soy Agar with 5% Sheep Blood (TSA II)–Bi-Plate " L007379 • Rev. 09 • December 2006 QUALITY CONTROL PROCEDURES I INTRODUCTION Group A Selective Strep Agar with 5% Sheep Blood (ssA) is a selective medium for use in the isolation and presumptive identification of group A streptococci from throat cultures and other specimens. Trypticase Soy Agar with 5% Sheep Blood (TSA II) is used for the growth of fastidious organisms and for the visualization of hemolytic reactions. The TSA II medium sector is marked "I" and the ssA medium sector is marked "II" in the bi-plate dish. II PERFORMANCE TEST PROCEDURE A. Group A Selective Strep Agar with 5% Sheep Blood 1. Inoculate representative samples with the cultures diluted to contain 103–104 CFU/0.01 mL. a. To each plate, add 0.01 mL of the dilution and streak for isolation. Make a stab in the primary streak area before streaking the rest of the plate. b. Place a Taxo™ A disc at the intersection of the first and second area of streaking on all plates inoculated with S. pyogenes strains. c. Incubate plates at 35 ± 2°C in an aerobic atmosphere supplemented with carbon dioxide. d. Include Trypticase Soy Agar with 5% Sheep Blood (TSA II) plates as nonselective controls for all organisms. 2. Examine plates after 18–24 h for beta hemolysis in the stabbed area and for amount of growth, inhibition, colony size and hemolytic reactions. Read and record the size of the zone around the Taxo A disc with S. -

Comparison of Throat Culture and Latex Agglutination Test for Streptococcal Pharyngitis

Comparison of Throat Culture and Latex Agglutination Test for Streptococcal Pharyngitis Paul M. Fischer, MD, and Pamela L. Mentrup, MLT Augusta, Georgia Numerous reports have recently appeared in the clinical microbiology litera ture that describe agglutination tests for identifying patients with group A streptococcal pharyngitis. These studies have indicated a close correlation between the results of the agglutination tests and traditional throat culturing. This paper describes a comparison study of 100 consecutive throat swab specimens using a commercially available agglutination test and routine throat culturing. The cultures were interpreted by an individual who was blinded to the agglutination test results. All agglutination testing was done by two laboratory members of a family practice office staff. The agglutination procedure was easy to perform and clear to interpret. The test sensitivity and specificity compared well with that reported in the literature from microbiol ogy laboratories. The new agglutination tests are useful in the office labora tory for the identification of group A streptococci. Their primary advantage compared with throat culturing is the rapid availability of test results. Most clinicians recognize the need to differ An additional problem with throat culturing has entiate group A streptococcal pharyngitis from been that clinicians are uncomfortable with the other infectious causes of pharyngitis because of 24- to 48-hour test time. Inconsistent patterns of the reduction in suppurative sequelae and clinical practice have therefore developed, includ rheumatic fever when streptococcal pharyngitis is ing waiting for the culture results before treating, treated with antibiotics.1 New evidence has also prescribing penicillin to all patients until the re supported the intuitive feeling of some clinicians sults are available, or treating all patients without that early antibiotic treatment will decrease the confirming the diagnosis by culture. -

Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance Pattern of Streptococcus Genus And

Journal of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases ISSN: 2345-5349 eISSN: 2345-5330 Prevalence and Antibiotic Resistance Pattern of Streptococcus Genus and Other Pathogens Isolated from Throat Culture Samples of Patients in Fatemeh Al- Zahra Hospital of Sari, Iran 1 2* 3 1 Mohsen Nazari , Mohammad Taha Ebrahimi , Niloofar Mobarezpour , Amin Sepehr 1Department of Bacteriology, Pasteur Institute of Iran, Tehran, Iran; 2Department of Microbiology, School of Medicine, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran; 3PPD Tuberculin Department, Razi Vaccine & Serum Research Institute, Karaj, Iran A R T I C L E I N F O A B S T R A C T Original Article Introduction: Tracheal tubes are among the primary means of infection transmission in hospitals. Therefore, identifying microbial agents transmitted via this route is necessary to control and prevent these infections. This study aimed Keywords: Antibiotic Resistance pattern, Tracheal Tube, Streptococcal to investigate the prevalence of pharyngeal-contaminating microorganisms and species their antibiotic resistance pattern. Methods: In this cross-sectional study, we used 117 pharyngeal swabs samples obtained from patients referred to Fatemeh Zahra Hospital of Sari, Iran, in 2018. The Samples were obtained using the Received: 15 Jul. 2020 sterile cotton swab from the throat and then cultured in the sheep blood agar. Received in revised form: 26 Jan. 2021 The positive colonies for the alpha-hemolytic test were subcultured on the Accepted: 26 Jan. 2021 Mueller-Hinton agar for further assays, including the susceptibility to optochin, DOI: 10.29252/JoMMID.8.4.143 catalase test, Gram's polychromatic stain, microscopic examination, pyrrolidonyl aminopeptidase (PYR) test, sensitization to bacitracin, and latex agglutination *Correspondence assay. -

Update Antibiotics: Why and Why Not to 2018

Antibiotics Why and Why Not 2018 Academic Detailing Service Planning committee Content Experts Clinical reviewers Paul Bonnar MD FRCPC, Assistant Professor Division of Infectious Disease, Dalhousie University, Medical Director, NSHA Antimicrobial Stewardship Program Jeannette Comeau MD MSc FRCPC FAAP, Pediatric Infectious Diseases Consultant, Assistant Professor, Dalhousie University, Medical Director, Infection Prevention and Control, Medical Lead, Antibiotic Stewardship IWK Health Centre Ian Davis MD CCFP FRCPC, Assistant Professor Divisions of Infectious Disease and Microbiology and Immunology, Dalhousie University Lynn Johnston MD MSc FRCPC, Professor Division of Infectious Disease, Dalhousie University Valerie Murphy BScPharm ACPR Antimicrobial Stewardship Pharmacist, Nova Scotia Health Authority, Central Zone Tasha Ramsey BScPharm, ACPR, PharmD, Assistant Professor, College of Pharmacy, Dalhousie University, Infectious Diseases and Internal Medicine Clinical Coordinator, Pharmacy Department, Nova Scotia Health Authority Kathy Slayter BScPharm, Pharm D, FCSHP, Clinical Pharmacy Specialist, Antimicrobial Stewardship/Infectious Diseases, Adjunct Assistant Professor Faculty of Medicine; Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases and Faculty of Graduate Studies, Dalhousie University, Canadian Center for Vaccinology Drug evaluation pharmacists Jennifer Fleming BScPharm ACPR Drug Evaluation Unit, Nova Scotia Health Kim Kelly BScPharm, Drug Evaluation Unit, Nova Scotia Health (retired) Family Physician Advisory Panel -

Microbiology Specimen Collection

Martin Health System Stuart, Florida Laboratory Services Microbiology Specimen Collection The recovery of pathogenic organisms responsible for an infectious process is dependent on proper collection and transportation of a specimen. An improperly collected or transported specimen may lead to failure to isolate the causative organism(s) of an infectious disease or may result in the recovery and subsequent treatment of contaminating organisms. Improper handling of specimens may also lead to accidental exposure to infectious material. GENERAL GUIDELINES FOR COLLECTION: 1. Follow universal precaution guidelines, treating all specimens as potentially hazardous. 2. Whenever possible, collect specimen before antibiotics are administered. 3. Collect the specimen from the actual site of infection, avoiding contamination from adjacent tissues or secretions. 4. Collect the specimen at optimal time i.e. Early morning sputum for AFB First voided specimen for urine culture Specimens ordered x 3 should be 24 hours apart (exception: Blood cultures which are collected as indicated by the physician) 5. Collect sufficient quantity of material for tests requested. 6. Use appropriate collection and transport container. Refer to the Microbiology Quick Reference Chart or to the specific source guidelines. Containers should always be tightly sealed and leak-proof 7. Label the specimen with the Patient’s First and Last Name Date of Birth Collection Date and Time Collector’s First and Last Name Source 8. Submit specimen in the sealed portion of a Biohazard specimen bag. 9. Place signed laboratory order in the outside pocket of the specimen bag. 10. Include any pertinent information i.e. recent travel or relocation, previous antibiotic therapy, unusual suspected organisms, method or environment of wound infliction 11. -

Blood Cultures - Aerobic & Anaerobic

Blood Cultures - Aerobic & Anaerobic Blood cultures are drawn into special bottles that contain a special medium that will support the growth and allow the detection of micro- organisms that prefer oxygen (aerobes) or that thrive in a reduced-oxygen environment (anaerobes). Multiple samples are usually collected. Routine standard of care indicates a minimum of Two Separate Sites or collected At Least 15 Minutes Apart. Multiple Collection/Multiple Site collection is done to aid in the detection of micro-organism s present in small numbers and/or may be released into the bloodstream intermittently. Samples must be incubated for several days before resulting to ensure that the sample is indeed negative before resulting out. Synergy Laboratories uses state of the art automated instrumentation that provides continuous monitoring. This allows for more rapid detection of samples that do contain bacteria or yeast. CONSIDER AEROBIC CONSIDER ANAEROBIC BLOOD CULTURES IN: BLOOD CULTURES IN: 1) New onset of fever, change in pattern of fever or unexplained clinical 1) Intra-abdominal infection instability. 2) Hemodynamic instability with or without fever if infection is a 2) Sepsis/septic shock from GI site possibility. 3) Necrotizing fasciitis or complicated 3) Possible endocarditis or graft infection. skin/soft tissue infection. 4) Unexplained hyperglycemia or 4) Severe oropharyngeal or dental hypotension. infection. 5) To assess cure of bacteremia. 5) Lung abscess or cavitary lesion. 6) Presence of a vascular catheter and 6) Massive blunt abdominal trauma. clinical instability. Body Fluid Specimens Selection Collect the specimen using strict aseptic technique. The patient should be fasting. If only one tube of fluid is available, the microbiology laboratory gets it first. -

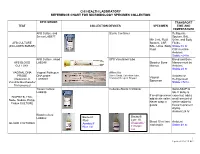

Chi Health Laboratory Reference Chart for Microbiology Specimen Collection

CHI HEALTH LABORATORY REFERENCE CHART FOR MICROBIOLOGY SPECIMEN COLLECTION EPIC ORDER TRANSPORT TEST COLLECTION DEVICES SPECIMEN TIME AND TEMPERATURE AFB Culture and Sterile Container Refrigerate Smear LAB877 Sputum, BAL, Min 2 mL Fluid: Urine, and Body AFB CULTURE Sputum, CSF, Fluids (INCLUDES SMEAR) BAL, Urine, Body Stable:72 hr. Fluid CSF must be Ambient Stable:<24 hr. AFB Culture, blood SPS Vacutainer tube Blood and Bone AFB BLOOD LAB246 Blood or Bone Marrow must be CULTURE Marrow Ambient Stable:24 hr VAGINAL DNA Vaginal Pathogen Affirm Kit PROBE DNA probe Sterile Swab, Collection Tube, Ambient or Vaginal (Detection of LAB3001 Transport Reagent Dropper Refrigerated Specimen Candida/Gardnerella/ Stable:<72 hr. Trichomonas) Tissue Culture Cultures-Sterile Container Send ASAP to LAB898 lab. If delay is If small specimen expected, add a BIOPSIES, FNA, add sterile saline. small amount of Node, Nodule, Polyp, Never wrap in sterile saline to Tissue CULTURE gauze tissue to prevent drying. Ambient 24 hr Blood Culture Bactec® LAB462 Bactec® Lytic 10 Plus+ Blood 10 ml into Ambient BLOOD CULTURES Anaerobic/ Aerobic/F each bottle Stable:48 hr. Blue Lid F Purple Lid 1 Updated 1/10/19 KG EPIC ORDER TRANSPORT TEST COLLECTION DEVICES SPECIMEN TIME AND TEMPERATURE Bordetella Nasopharyngeal Freeze pertussis/ Mini Swab Stable: 3 months BORDETELLA Parapertussis by PERTUSSIS PCR PCR LAB923 (discard large UVTM swab) Universal Viral Transport Media Mini-tip ESwab Bacterial Culture Chlamydia by PCR Dirty Urine First (Urine) LAB5763 Morning Void (No clean catch CHLAMYDIA Chlamydia/ or midstream Stable at 2-30° TRACHOMATIS by Gonorrhea by PCR Cobas® Urine PCR Media tube urine). -

Strep a Test Result, Streak the Culture Plate with the Swab Before Starting the Sure- Summary Vue Signature Strep a Test Procedure

Process the swab as soon as possible after collecting the specimen. If your lab requires a culture result as well PERFORMANCE CHARACTERISTICS as the Sure-Vue Signature Strep A Test result, streak the culture plate with the swab before starting the Sure- Summary Vue Signature Strep A Test procedure. The extraction reagents will cause the specimen to become nonviable. The study results in this section show that the sensitivities of the Sure-Vue Signature Strep A Test and the standard 5 0 single swab culture method are not statistically different. The study also compared the Sure-Vue Signature / Because the Sure-Vue Signature Strep A Test does not require live organisms for processing, you may store 1 Strep A Test to Rigorous Gold Standard and another commercially available rapid test, Thermo BioStar’s 1 and transport the swabs dry. If you do not perform the Sure-Vue Signature Strep A Test immediately, store ® , Strep A OIA Max Test***. 0 - the swabs either at room or refrigerated temperature for up to 48 hours. The swabs and the test kit must be 2 at room temperature before you perform the test. 1 Comparison of the Performances of Sure-Vue Signature Strep A Test, Strep A OIA Max Test and Standard 8 3 Strep A Test Single Swab Culture Method, by Using Rigorous Gold Standard (“RGS”; Multiple Sample Swab Culture plus . v QUALITY CONTROL Broth Enhanced Pledget Culture) as the Gold Standard e Internal Procedural Controls R CLIA Complexity: Waived In a hospital clinical lab field evaluation, two swabs (A and B) were collected from each of 302 patients The Sure-Vue Signature Strep A Test provides three levels of procedural controls with each test run. -

Investigation of Throat Related Specimens

UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations 2014 Investigation of Throat Related Specimens SEPTEMBER 22 - AUGUST 18 BETWEEN ON CONSULTED WAS DOCUMENT THIS - DRAFT Issued by the Standards Unit, Microbiology Services, PHE Bacteriology | B 9 | Issue no: di+ | Issue date: dd.mm.yy <tab+enter> | Page: 1 of 29 © Crown copyright 2014 Investigation of Throat Related Specimens Acknowledgments UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations (SMIs) are developed under the auspices of Public Health England (PHE) working in partnership with the National Health Service (NHS), Public Health Wales and with the professional organisations whose logos are displayed below and listed on the website http://www.hpa.org.uk/SMI/Partnerships. SMIs are developed, reviewed and revised by various working groups which are overseen by a steering committee (see http://www.hpa.org.uk/SMI/WorkingGroups). The contributions of many individuals in clinical, specialist and reference laboratories2014 who have provided information and comments during the development of this document are acknowledged. We are grateful to the Medical Editors for editing the medical content. For further information please contact us at: SEPTEMBER Standards Unit 22 Microbiology Services - Public Health England 61 Colindale Avenue London NW9 5EQ AUGUST E-mail: [email protected] 18 Website: http://www.hpa.org.uk/SMI UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations are produced in association with: BETWEEN ON CONSULTED WAS DOCUMENT THIS - DRAFT Bacteriology | B 9 | Issue no: di+ | Issue date: dd.mm.yy <tab+enter> | Page: 2 of 29 UK Standards for Microbiology Investigations | Issued by the Standards Unit, Public Health England Investigation of Throat Related Specimens Contents ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .......................................................................................................... 2 AMENDMENT TABLE ............................................................................................................ -

Antimicrobial Use in Long‐Term–Care Facilities • Author(S): Lindsay E

Antimicrobial Use in Long‐Term–Care Facilities • Author(s): Lindsay E. Nicolle , MD, David W. Bentley , MD, Richard Garibaldi , MD, Ellen G. Neuhaus , MD, Philip W. Smith , MD Source: Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology, Vol. 21, No. 8 (August 2000), pp. 537-545 Published by: The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/501798 . Accessed: 06/06/2011 18:37 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at . http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and The Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Infection Control and Hospital Epidemiology. -

Specimen Collection & Transport Guide

2018-2019 Specimen Collection & Transport Guide Visit our online version at QuestDiagnostics.com/TestDirectory Return to Table of Contents DirectorySpecimen of Collection Services & Transport Guide 2018-2019 QuestDiagnostics.com The CPT® codes provided in this document are based on AMA guidelines and are for informational purposes only. CPT® coding is the sole responsibility of the billing party. Please direct any questions regarding coding to the payer being billed. Quest, Quest Diagnostics, any associated logos, and all associated Quest Diagnostics registered and unregistered trademarks are the property of Quest Diagnostics. All third party marks—® and ™—are the property of their respective owners. © 2018 Quest Diagnostics Incorporated. All rights reserved. Table of Contents Directory of Services 5 Bacterial Identification (Aerobic) and Susceptibility Bacterial Idntifcaiton (Aerobic) Only Where to Find Information ................................................................7 Susceptibility Panel, Aerobic Bacterium About Us: The World’s Leading Laboratory .....................................7 Fungal Isolate Identification Test Additions After Submission of Specimen ..................................7 Mycobacterium Identification ..........................................................48 Reporting ..........................................................................................7 Bacterial Vaginosis & Vaginitis .......................................................48 Confidentiality ...................................................................................8 -

Throat Culture Screen for Presumptive Identification of Group a Streptococci

Collection, Culture, and Interpretation of a Throat Culture Screen for Presumptive Identification of Group A Streptococci Preanalytical Steps Analytical Steps Required Quality Control (QC) Test Procedure Before Collection and Culture A 1 1 Inoculation of Agar Plate 2 Primary Inoculation Media • Use ONE SSA plate per patient. • Label plate bottom, not cover. • Use ONLY Selective Strep Agar (SSA). Isolation Streak Include patient’s first name, last name, and unique identifier. 3 Include inoculation date. Maintain documentation on manufacturer’s quality control performance. 44 • Inoculate plate with specimen swab. Cover ≤1/4 of agar surface. • For each new shipment and each new lot number, Use sterile inoculating loop to streak plate (See Diagram A). ■ Document receipt date, lot number and expiration date. B ■ Document any variations in the physical characteristics of the media. • Apply TAXO A disk. Remove one disk with clean forceps and place disk on first • If QC fails, quadrant. ■ Take corrective action; and Do not allow the forceps to touch agar surface. ■ Document the action in the corrective action log. Incubation of Agar Plate TAXO A Disks o Presumptive Group A • Incubate at 35–37 C for 24–48 hours. Streptococci • Incubate agar plates BOTTOM SIDE UP. • Use ONLY TAXO A Disks (0.04 units bacitracin). DO NOT incubate agar plates cover side up. ■ Test each new shipment and each new lot number before patient testing • Examine agar plates at 24 hours; document results. Re-incubate negative by using the following organisms: agar plates for an additional 24 hours and document final results. Streptococcus pyogenes ATCC 12384 (or equivalent) — Positive Control Observe the SSA plate for the appearance of translucent or opaque white- Test Results to-gray–colored colonies surrounded by a zone of beta hemolysis and a • Positive: Appearance of translucent or opaque white-to-gray–colored zone of no colony growth around the TAXO A disk.