Congenital Heart Defects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate

Neonatal Nursing Education Brief: How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate https://www.seattlechildrens.org/healthcare- professionals/education/continuing-medical-nursing-education/neonatal- nursing-education-briefs/ Cardiac defects are commonly seen and are the leading cause of death in the neonate. Prompt suspicion and recognition of congenital heart defects can improve outcomes. An ECHO is not needed to make a diagnosis. Cardiac defects, congenital heart defects, NICU, cardiac assessment How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate Purpose and Goal: CNEP # 2092 • Understand the signs of congenital heart defects in the neonate. • Learn to recognize and detect heart defects in the neonate. None of the planners, faculty or content specialists has any conflict of interest or will be presenting any off-label product use. This presentation has no commercial support or sponsorship, nor is it co-sponsored. Requirements for successful completion: • Successfully complete the post-test • Complete the evaluation form Date • December 2018 – December 2020 Learning Objectives • Describe the risk factors for congenital heart defects. • Describe the clinical features of suspected heart defects. • Identify 2 approaches for recognizing congenital heart defects. Introduction • Congenital heart defects may be seen at birth • They are the most common congenital defect • They are the leading cause of neonatal death • Many neonates present with symptoms at birth • Some may present after discharge • Early recognition of CHD -

Congenital Cardiovascular Defects

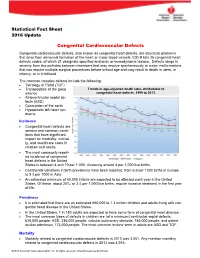

Statistical Fact Sheet 2016 Update Congenital Cardiovascular Defects Congenital cardiovascular defects, also known as congenital heart defects, are structural problems that arise from abnormal formation of the heart or major blood vessels. ICD-9 lists 25 congenital heart defects codes, of which 21 designate specified anatomic or hemodynamic lesions. Defects range in severity from tiny pinholes between chambers that may resolve spontaneously to major malformations that can require multiple surgical procedures before school age and may result in death in utero, in infancy, or in childhood. The common complex defects include the following: Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) Transposition of the great Trends in age-adjusted death rates attributable to arteries congenital heart defects, 1999 to 2013. Atrioventricular septal de- fects (ASD) Coarctation of the aorta Hypoplastic left heart syn- drome Incidence Congenital heart defects are serious and common condi- tions that have significant impact on morbidity, mortali- ty, and healthcare costs in children and adults. The most commonly report- ed incidence of congenital heart defects in the United States is between 4 and 10 per 1,000, clustering around 8 per 1,000 live births. Continental variations in birth prevalence have been reported, from 6.9 per 1000 births in Europe to 9.3 per 1000 in Asia. An estimated minimum of 40,000 infants are expected to be affected each year in the United States. Of these, about 25%, or 2.4 per 1,000 live births, require invasive treatment in the first year of life. Prevalence It is estimated that there are an estimated 650,000 to 1.3 million children and adults living with con- genital heart disease in the United States. -

Congenital Heart Disease Parent FAQ

Congenital Heart Disease Parent FAQ achd.stanfordchildrens.org | achd.stanfordhealthcare.org About Congenital Heart Disease What is congenital heart disease? Congenital heart disease, also called congenital heart defect (CHD), is a heart problem that a baby is born with. When the heart forms in the womb, it develops incorrectly and does not work properly, which changes how the blood flows through the heart. What causes congenital heart defects? In most cases, there is no clear cause. It can be linked to something out of the ordinary happening during gestation, including a viral infection or exposure to environmental factors. Or, it may be linked to a single gene defect or chromosome abnormalities. How common is CHD in the United States among children? Congenital heart defects are the most common birth defects in children in the United States. Approximately 1 in 100 babies are born with a heart defect. What are the most common types of congenital heart defects in children? In general, CHDs disrupt the flow of blood in the heart as it passes to the lungs or to the body. The most common congenital heart defects are abnormalities in the heart valves or a hole between the chambers of the heart (ventricles). Examples include ventricular septal defect (VSD), atrial septal defect (ASD), and bicuspid aortic valve. At the Betty Irene Moore Children’s Heart Center at Stanford Children’s Health, we are known across the nation and world for treating some of the most complex congenital heart defects with outstanding outcomes. Congenital Heart Disease Parent FAQ | 2 Is CHD preventable? In some cases, it could be preventable. -

Pulmonary-Atresia-Mapcas-Pavsdmapcas.Pdf

Normal Heart © 2012 The Children’s Heart Clinic NOTES: Children’s Heart Clinic, P.A., 2530 Chicago Avenue S, Ste 500, Minneapolis, MN 55404 West Metro: 612-813-8800 * East Metro: 651-220-8800 * Toll Free: 1-800-938-0301 * Fax: 612-813-8825 Children’s Minnesota, 2525 Chicago Avenue S, Minneapolis, MN 55404 West Metro: 612-813-6000 * East Metro: 651-220-6000 © 2012 The Children’s Heart Clinic Reviewed March 2019 Pulmonary Atresia, Ventricular Septal Defect and Major Aortopulmonary Collateral Arteries (PA/VSD/MAPCAs) Pulmonary atresia (PA), ventricular septal defect (VSD) and major aortopulmonary collateral arteries (MAPCAs) is a rare type of congenital heart defect, also referred to as Tetralogy of Fallot with PA/MAPCAs. Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is the most common cyanotic heart defect and occurs in 5-10% of all children with congenital heart disease. The classic description of TOF includes four cardiac abnormalities: overriding aorta, right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH), large perimembranous ventricular septal defect (VSD), and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (RVOTO). About 20% of patients with TOF have PA at the infundibular or valvar level, which results in severe right ventricular outflow tract obstruction. PA means that the pulmonary valve is closed and not developed. When PA occurs, blood can not flow through the pulmonary arteries to the lungs. Instead, the child is dependent on a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) or multiple systemic collateral vessels (MAPCAs) to deliver blood to the lungs for oxygenation. These MAPCAs usually arise from the de- scending aorta and subclavian arteries. Commonly, the pulmonary arteries are abnormal, with hypoplastic (small and underdeveloped) central and branch pulmonary arteries and/ or non-confluent central pulmonary arteries. -

Transcatheter Device Closure of Atrial Septal Defect in Dextrocardia with Situs Inversus Totalis

Case Report Nepalese Heart Journal 2019; Vol 16(1), 51-53 Transcatheter device closure of atrial septal defect in dextrocardia with situs inversus totalis Kiran Prasad Acharya1, Chandra Mani Adhikari1, Aarjan Khanal2, Sachin Dhungel1, Amrit Bogati1, Manish Shrestha3, Deewakar Sharma1 1 Department of Cardiology, Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Kathmandu Medical College, Kathmandu,Nepal 3 Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal Corresponding Author: Chandra Mani Adhikari Department of Cardiology Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre Kathmandu, Nepal Email: [email protected] Cite this article as: Acharya K P, Adhikari C M, Khanal A, et al. Transcatheter device closure of atrial septal defect in dextrocardia with situs inversus totalis. Nepalese Heart Journal 2019; Vol 16(1), 51-53 Received date: 17th February 2019 Accepted date: 16th April 2019 Abstract Only few cases of Device closure of atrial septal defect in dextrocardia with situs inversus totalis has been reported previously. We present a case of a 36 years old male, who had secundum type of atrial septal defect in dextrocardia with situs inversus totalis. ASD device closure was successfully done. However, we encountered few technical difficulties in this case which are discussed in this case review. Keywords: atrial septal defect; dextrocardia; transcatheter device closure, DOI: https://doi.org/10.3126/njh.v16i1.23901 Introduction There are only two case reported of closure of secundum An atrial septal defect (ASD) is an opening in the atrial ASD associated in patients with dextrocardia and situs inversus septum, excluding a patent foramen ovale.1 ASD is a common totalis. -

Tetralogy of Fallot.” These Podcasts Are Designed to Give Medical Students an Overview of Key Topics in Pediatrics

PedsCases Podcast Scripts This is a text version of a podcast from Pedscases.com on “Tetralogy of Fallot.” These podcasts are designed to give medical students an overview of key topics in pediatrics. The audio versions are accessible on iTunes or at www.pedcases.com/podcasts. Tetralogy of Fallot Developed by Katie Girgulis, Dr. Andrew Mackie, and Dr. Karen Forbes for PedsCases.com. April 14, 2017 Introduction Hello, my name is Katie Girgulis and I am a medical student at the University of Alberta. This podcast was developed with the help of Dr. Andrew Mackie and Dr. Karen Forbes. Dr. Mackie is a pediatric cardiologist at the Stollery Children’s Hospital, and Dr. Forbes is a pediatrician and medical educator at the Stollery Children’s Hospital. This podcast is about the cardiac condition Tetralogy of Fallot (ToF). For teaching on the general approach to pediatric heart murmurs, please check out the ‘Evaluation of a Heart Murmur’ podcast on Pedscases.com. Slide 2 Learning Objectives By the end of this podcast, the learner will be able to: 1) Recognize the clinical presentations of ToF 2) Describe the four anatomical characteristics of ToF 3) Describe the pathophysiology of the murmur in ToF 4) Formulate initial steps when ToF is suspected 5) Delineate the treatment of hypercyanotic episodes 6) Summarize the definitive treatment for ToF Slide 3 Case – Baby Josh Let’s start with a clinical case: You are working with Dr. Smith, a family physician, during your family medicine rotation. Josh is a 4-month-old infant who is here for a well-baby check. -

Congenital Heart Disease: Recognition and Treatment Options – Anna Gelzer

CONGENITAL HEART DISEASE: RECOGNITION AND TREATMENT OPTIONS – ANNA GELZER Prevalence and Frequency Congenital heart disease in dogs: ≤ 1% (Canine clinic population of U Penn 1992) Cats estimated < 0.2% Prevalence likely underestimated (perinatal death, no murmur) Small % of cardiac disease overall, but most common in animals < 1 y old Common congenital cardiac defects in dogs (in the order of frequency): Subaortic stenosis (SAS) Pulmonic stenosis (PS) Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) Tricuspid valve dysplasia (TVD) Ventricular septal defect (VSD) Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) Persistent right aortic arch (PRAA) Atrial septal defects (ASD) Mitral valve dysplasia (MVD) Persistent left carnial venal cava Congenital cardiac defects in cats (in the order of frequency): Mitral valve dysplasia (MVD) Ventricular septal defect (VSD) Endocardial cushion defect (ASD+VSD) Patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) Aortic stenosis (SAS) Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) Pulmonic stenosis (PS) Atrial septal defects (ASD) Tricuspid valve dysplasia (TVD) Physical exam finding in animals with most common congenital heart disease: The simple congenital heart defects are normally identified by the presence of a heart murmur. From the clinical examination, by localizing the heart murmur, identifying its radiation, assessing the precordial impulse and the peripheral pulse, a differential diagnosis list can be drawn up. The table summarizes the findings for some of the common defects identified in dogs and cats. Note, for these simple defects, mucus membrane color is normal (pink). -

Association of Hand Anomalies with Congenital Heart Lesions in Mentally Retarded, State- Institutionalized Patients Marian Grace Jordison Yale University

Yale University EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library School of Medicine 1968 Association of hand anomalies with congenital heart lesions in mentally retarded, state- institutionalized patients Marian Grace Jordison Yale University Follow this and additional works at: http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl Recommended Citation Jordison, Marian Grace, "Association of hand anomalies with congenital heart lesions in mentally retarded, state-institutionalized patients" (1968). Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library. 2756. http://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ymtdl/2756 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Medicine at EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yale Medicine Thesis Digital Library by an authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information, please contact [email protected]. YALE MEDICAL LIBRARY 9002 01065 5752 seek ^ j IptxL-ffij y Li: Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from The National Endowment for the Humanities and the Arcadia Fund https://archive.org/details/associationofhanOOjord ASSOCIATION OF HAND ANOMALIES WITH CONGENITAL HEART LESIONS IN MENTALLY RETARDED, STATE- INSTITUTIONALIZED PATIENTS Marian Grace Jordison B.A. Stanford University, 1964 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Medicine Department of Epidemiology & Public Health Yale University School of Medicine April, 1968 y/3. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Introduction. 1 Review of the literature. 3 I. Holt-Oram syndrome. 3 II. Epidemiology of congenital malformations. 6 A. Incidence. 6 B. -

Tetralogy of Fallot

Tetralogy of Fallot Rebecca E. Gompf, DVM, MS, DACVIM (Cardiology) BASIC INFORMATION capabilities usually confirms the diagnosis and the severity of the Description problem. Because many veterinarians do not have the Doppler Tetralogy of Fallot is a congenital heart defect that is present at equipment, your pet may be referred to a veterinary specialist for birth. It arises from three primary, spontaneous defects and a fourth the procedure. Laboratory tests may be recommended to evaluate defect that results from the other three. The three main defects are the body’s response to the decreased oxygen levels. pulmonic stenosis, which is a narrowing of the pulmonary artery, which travels from the right side of the heart to the lungs; an over- TREATMENT AND FOLLOW-UP riding aorta, in which the aorta is too large and drains blood from both the right and left sides of the heart; and a ventricular sep- Treatment Options tal defect, which is a hole between the two large chambers of the Animals with tetralogy of Fallot are treated medically. Children heart. The fourth defect is thickening of the right ventricle, which with this condition undergo complete repair via open heart sur- arises from the need to generate more energy to push blood into gery, but dogs and cats do not tolerate being on a heart bypass the aorta through the narrowed pulmonary artery. machine long enough to do a total repair of their defects. Some CAUSE surgeries have been tried to shunt extra blood through the lungs, Tetralogy of Fallot is inherited in some breeds, but the inheritance but these are not routinely done in animals. -

Personalized Genetic Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Defects in Newborns

Journal of Personalized Medicine Review Personalized Genetic Diagnosis of Congenital Heart Defects in Newborns Olga María Diz 1,2,† , Rocio Toro 3,† , Sergi Cesar 4, Olga Gomez 5,6, Georgia Sarquella-Brugada 4,7,*,‡ and Oscar Campuzano 2,7,8,*,‡ 1 UGC Laboratorios, Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, 11009 Cadiz, Spain; [email protected] 2 Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics Department, Hospital Clinic of Barcelona, Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Universitat de Barcelona, 08950 Barcelona, Spain 3 Medicine Department, School of Medicine, Cádiz University, 11519 Cadiz, Spain; [email protected] 4 Arrhythmia, Inherited Cardiac Diseases and Sudden Death Unit, Institut de Recerca Sant Joan de Déu, Hospital Sant Joan de Déu, University of Barcelona, 08007 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 5 Fetal Medicine Research Center, BCNatal-Barcelona Center for Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine (Hospital Clínic and Hospital Sant Joan de Deu), Institut d’Investigacions Biomèdiques August Pi i Sunyer (IDIBAPS), Universitat de Barcelona, 08950 Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] 6 Centre for Biomedical Research on Rare Diseases (CIBER-ER), 28029 Madrid, Spain 7 Medical Science Department, School of Medicine, University of Girona, 17003 Girona, Spain 8 Centro de Investigación Biomédica en Red, Enfermedades Cardiovasculares (CIBER-CV), 28029 Madrid, Spain * Correspondence: [email protected] (G.S.-B.); [email protected] (O.C.) † Equally as co-first authors. ‡ Contributed equally as co-senior authors. Citation: Diz, O.M.; Toro, R.; Cesar, Abstract: Congenital heart disease is a group of pathologies characterized by structural malforma- S.; Gomez, O.; Sarquella-Brugada, G.; tions of the heart or great vessels. -

FACTS Small Hearts – Big Challenges Congenital Heart Defects (CHD) in Children, Youth and Adults

FACTS Small Hearts – Big Challenges Congenital Heart Defects (CHD) in Children, Youth and Adults OVERVIEW As of 2002, it was estimated that 650,000 to 1.3 Often viewed as a problem of adults, cardiovascular million Americans had CHD. More recent studies 10 disease also exacts a terrible toll on the young. show these numbers could be increasing. Congenital cardiovascular defects, also known as CHD are about 60 times more prevalent than 11,12,13 congenital heart defects (CHD), are the most childhood cancers. common birth defect in the U.S.1 and the leading 2 Although the mortality rate for CHD has sharply killer of infants with birth defects. The incidence of 14 CHD ranges between 4 and 10 per 1,000 live births.3 declined since 1994, CHD is still a major killer. Nearly one in three infants who dies from a birth Tragically, more than 1,500 of them do not live to 2 celebrate their first birthday.2 Beyond the terrible defect has a heart defect. CHD directly caused or contributed to the deaths of death toll, physical and mental suffering, and lost 3 potential and productivity that CHD causes, it also 5,359 in 2008. comes with a steep price tag. In 2004, hospital costs In 2007, 189,000 life years were lost before age 55 4 due to deaths from heart defects existing at birth – for all individuals with CHD totaled $2.6 billion. nearly equivalent to the life-years lost from leukemia, prostate cancer and Alzheimer’s disease But there is still real reason for hope. -

Tetralogy of Fallot

Department Of Health and Mental Hygiene Prevention and Health Promotion Administration Office for Genetics and People with Special Health Care Needs Tetralogy of Fallot What is Tetralogy of Fallot? Heart defect which is present at birth (congenital) Most common type of critical congenital heart defect Consists of four defects of the heart and the major blood vessels: 1. Ventricular Septal Defect (VSD) - a hole between the right and left ventricles (bottom chambers) of the heart 2. Narrowing of the pulmonary outflow tract - the valve and artery that connects the heart with the lungs 3. Overriding Aorta - aorta usually takes oxygen rich blood to the body from the left ventricle to the body. An overriding aorta is shifted and takes blood from the right and left ventricles, reducing the amount of oxygen in the blood that goes to the body 4. Right Ventricular Hypertrophy - thickened wall of the right ventricle What is the cause of Tetralogy of Fallot? There is no known cause, but there are certain risk factors which will increase the chance of this condition occurring: 1. Drinking alcohol regularly during pregnancy 2. Maternal diabetes 3. Mother’s age (over 40) 4. Poor nutrition during pregnancy 5. Rubella or other viral illnesses during pregnancy Infants born with Tetralogy of Fallot are more likely to have chromosomal (genetic) disorders such as Down Syndrome or DiGeorge Syndrome Signs and Symptoms Bluish skin color, especially around lips and fingernails Clubbing of fingers (broadening and blunting of tips) Poor feeding and poor growth Fainting episodes How is Tetralogy of Fallot treated? Medicines are often used to improve blood flow and circulation.