How to Recognize a Suspected Cardiac Defect in the Neonate

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Generalized Edema Resulting from Mixed Intestinal Infection by Entamoebia Histolytica and E

Case Report JOJ Case Stud Volume 12 Issue 2 -April 2021 Copyright © All rights are reserved by Ajite Adebukola DOI: 10.19080/JOJCS.2021.12.555833 Generalized Edema Resulting from Mixed Intestinal Infection by Entamoebia Histolytica and E. Coli in a Nigerian Female Adolescent: A Case Report Ajite Adebukola1,2*, Oluwayemi Oludare1,2 and Fatunla Odunayo2 1Department of Paediatrics, Ekiti State University, Nigeria 2Department of Paediatrics, Ekiti State University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria Submission: March 15, 2021; Published: April 08, 2021 *Corresponding author: Ajite Adebukola, Consultant Paediatrician, Department of Paediatrics, Ekiti State University, Ado Ekiti, Nigeria Abstract Amoebiasis, a clinical condition caused by Entamoeba histolytica does not usually present with generalized oedema known as anarsarca. We present a case of an adolescent female Nigerian who was admitted on account of chronic diarrhea and anarsarca in a tertiary hospital, Southwest Nigeria. There was no proteinuria. She however had cyst of E. histolytica and growth of E. coli in her stool; she also had E. coli isolated in her urine. She had hypoproteinaemia (35.2g/L) and hypoalbuminaemia (21.3g/L) as well as hypokalemia (2.97mmol/L). Symptoms resolved Entamoeba histolytica and Escherichia coli bacteria may be responsible for the worse clinical manifestations of Amoebiasis and biochemical parameters normalized following treatment with Nitrofurantoin, Tinidazole and Ciprofloxacin. A mixed infection of Keywords: Amoebiasis; Chronic diarrhea; Hypoproteinaemia; Anasarca Introduction Amoebiasis, caused by the protozoan Entamoeba histolytica of amenorrhoea. is an infection that frequently manifests clinically with symptoms recurrent generalized body swelling, and a seven-month history of abdominal pain, diarrhoea, dysentery and weight loss [1,2]. -

Ehrlichiosis and Anaplasmosis Are Tick-Borne Diseases Caused by Obligate Anaplasmosis: Intracellular Bacteria in the Genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma

Ehrlichiosis and Importance Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are tick-borne diseases caused by obligate Anaplasmosis: intracellular bacteria in the genera Ehrlichia and Anaplasma. These organisms are widespread in nature; the reservoir hosts include numerous wild animals, as well as Zoonotic Species some domesticated species. For many years, Ehrlichia and Anaplasma species have been known to cause illness in pets and livestock. The consequences of exposure vary Canine Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, from asymptomatic infections to severe, potentially fatal illness. Some organisms Canine Hemorrhagic Fever, have also been recognized as human pathogens since the 1980s and 1990s. Tropical Canine Pancytopenia, Etiology Tracker Dog Disease, Ehrlichiosis and anaplasmosis are caused by members of the genera Ehrlichia Canine Tick Typhus, and Anaplasma, respectively. Both genera contain small, pleomorphic, Gram negative, Nairobi Bleeding Disorder, obligate intracellular organisms, and belong to the family Anaplasmataceae, order Canine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, Rickettsiales. They are classified as α-proteobacteria. A number of Ehrlichia and Canine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Anaplasma species affect animals. A limited number of these organisms have also Equine Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, been identified in people. Equine Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, Recent changes in taxonomy can make the nomenclature of the Anaplasmataceae Tick-borne Fever, and their diseases somewhat confusing. At one time, ehrlichiosis was a group of Pasture Fever, diseases caused by organisms that mostly replicated in membrane-bound cytoplasmic Human Monocytic Ehrlichiosis, vacuoles of leukocytes, and belonged to the genus Ehrlichia, tribe Ehrlichieae and Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, family Rickettsiaceae. The names of the diseases were often based on the host Human Granulocytic Ehrlichiosis, species, together with type of leukocyte most often infected. -

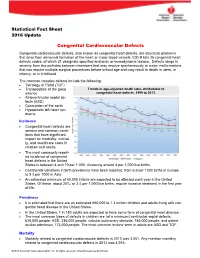

Congenital Cardiovascular Defects

Statistical Fact Sheet 2016 Update Congenital Cardiovascular Defects Congenital cardiovascular defects, also known as congenital heart defects, are structural problems that arise from abnormal formation of the heart or major blood vessels. ICD-9 lists 25 congenital heart defects codes, of which 21 designate specified anatomic or hemodynamic lesions. Defects range in severity from tiny pinholes between chambers that may resolve spontaneously to major malformations that can require multiple surgical procedures before school age and may result in death in utero, in infancy, or in childhood. The common complex defects include the following: Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) Transposition of the great Trends in age-adjusted death rates attributable to arteries congenital heart defects, 1999 to 2013. Atrioventricular septal de- fects (ASD) Coarctation of the aorta Hypoplastic left heart syn- drome Incidence Congenital heart defects are serious and common condi- tions that have significant impact on morbidity, mortali- ty, and healthcare costs in children and adults. The most commonly report- ed incidence of congenital heart defects in the United States is between 4 and 10 per 1,000, clustering around 8 per 1,000 live births. Continental variations in birth prevalence have been reported, from 6.9 per 1000 births in Europe to 9.3 per 1000 in Asia. An estimated minimum of 40,000 infants are expected to be affected each year in the United States. Of these, about 25%, or 2.4 per 1,000 live births, require invasive treatment in the first year of life. Prevalence It is estimated that there are an estimated 650,000 to 1.3 million children and adults living with con- genital heart disease in the United States. -

Cutaneous Manifestations of Abdominal Arteriovenous Fistulas

Cutaneous Manifestations of Abdominal Arteriovenous Fistulas Jessica Scruggs, MD; Daniel D. Bennett, MD Abdominal arteriovenous (A-V) fistulas may be edema.1-3 We report a case of abdominal aortocaval spontaneous or secondary to trauma. The clini- fistula presenting with lower extremity edema, ery- cal manifestations of abdominal A-V fistulas are thema, and cyanosis that had been previously diag- variable, but cutaneous findings are common and nosed as venous stasis dermatitis. may be suggestive of the diagnosis. Cutaneous physical examination findings consistent with Case Report abdominal A-V fistula include lower extremity A 51-year-old woman presented to the emergency edema with cyanosis, pulsatile varicose veins, department with worsening lower extremity swelling, and scrotal edema. redness, and pain. Her medical history included a We present a patient admitted to the hospital diagnosis of congestive heart failure, chronic obstruc- with lower extremity swelling, discoloration, and tive pulmonary disease, hepatitis C virus, tobacco pain, as well as renal insufficiency. During a prior abuse, and polysubstance dependence. Swelling, red- hospitalization she was diagnosed with venous ness, and pain of her legs developed several years stasis dermatitis; however, CUTISher physical examina- prior, and during a prior hospitalization she had been tion findings were not consistent with that diagno- diagnosed with chronic venous stasis dermatitis as sis. Imaging studies identified and characterized well as neurodermatitis. an abdominal aortocaval fistula. We propose that On admission, the patient had cool lower extremi- dermatologists add abdominal A-V fistula to the ties associated with discoloration and many crusted differential diagnosis of patients presenting with ulcerations. Aside from obesity, her abdominal exam- lower extremity edema with cyanosis, and we ination was unremarkable and no bruits were noted. -

Congenital Heart Disease Parent FAQ

Congenital Heart Disease Parent FAQ achd.stanfordchildrens.org | achd.stanfordhealthcare.org About Congenital Heart Disease What is congenital heart disease? Congenital heart disease, also called congenital heart defect (CHD), is a heart problem that a baby is born with. When the heart forms in the womb, it develops incorrectly and does not work properly, which changes how the blood flows through the heart. What causes congenital heart defects? In most cases, there is no clear cause. It can be linked to something out of the ordinary happening during gestation, including a viral infection or exposure to environmental factors. Or, it may be linked to a single gene defect or chromosome abnormalities. How common is CHD in the United States among children? Congenital heart defects are the most common birth defects in children in the United States. Approximately 1 in 100 babies are born with a heart defect. What are the most common types of congenital heart defects in children? In general, CHDs disrupt the flow of blood in the heart as it passes to the lungs or to the body. The most common congenital heart defects are abnormalities in the heart valves or a hole between the chambers of the heart (ventricles). Examples include ventricular septal defect (VSD), atrial septal defect (ASD), and bicuspid aortic valve. At the Betty Irene Moore Children’s Heart Center at Stanford Children’s Health, we are known across the nation and world for treating some of the most complex congenital heart defects with outstanding outcomes. Congenital Heart Disease Parent FAQ | 2 Is CHD preventable? In some cases, it could be preventable. -

Pedal Edema in Older Adults Jennifer M

www.aging.arizona.edu July 2013 (updated May2015) ELDER CARE A Resource for Interprofessional Providers Pedal Edema in Older Adults Jennifer M. Vesely, MD, Teresa Quinn, MD, and Donald Pine, MD, Family Medicine Residency, University of Minnesota Pedal edema is the accumulation of fluid in the feet and pedal edema, which is more common in older adults, is lower legs. It is typically caused by one of two mechanisms. often multifactorial and may reflect a systemic process. The first is venous edema, caused by increased capillary Treating the underlying cause can often lessen the edema. filtration and retention of protein-poor fluid from the Table 1 lists common and less common causes of bilateral venous system into the interstitial space. The other pedal edema. mechanism is lymphatic edema, caused by obstruction or In addition to seeking evidence for the conditions listed in dysfunction of lymphatic outflow from the legs resulting in Table 1, certain clues in the patient’s presentation might accumulation of protein-rich interstitial fluid. These two point to a particular cause of edema. In particular, the mechanisms can operate independently or together. duration of edema and presence of pain should be noted. Regardless of the mechanism, chronic bilateral pedal Acute onset and presence of edema for less than 72 hours edema is detrimental to the health and quality of life of suggests the possibility of venous thrombosis and steps older adults. Besides alterations in cosmetic appearance or should be taken to exclude that diagnosis. Edema due to the discomfort it may cause, older adults with pedal edema chronic venous insufficiency is often associated with a dull often experience gait disturbance with decreased mobility aching pain. -

Pulmonary-Atresia-Mapcas-Pavsdmapcas.Pdf

Normal Heart © 2012 The Children’s Heart Clinic NOTES: Children’s Heart Clinic, P.A., 2530 Chicago Avenue S, Ste 500, Minneapolis, MN 55404 West Metro: 612-813-8800 * East Metro: 651-220-8800 * Toll Free: 1-800-938-0301 * Fax: 612-813-8825 Children’s Minnesota, 2525 Chicago Avenue S, Minneapolis, MN 55404 West Metro: 612-813-6000 * East Metro: 651-220-6000 © 2012 The Children’s Heart Clinic Reviewed March 2019 Pulmonary Atresia, Ventricular Septal Defect and Major Aortopulmonary Collateral Arteries (PA/VSD/MAPCAs) Pulmonary atresia (PA), ventricular septal defect (VSD) and major aortopulmonary collateral arteries (MAPCAs) is a rare type of congenital heart defect, also referred to as Tetralogy of Fallot with PA/MAPCAs. Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF) is the most common cyanotic heart defect and occurs in 5-10% of all children with congenital heart disease. The classic description of TOF includes four cardiac abnormalities: overriding aorta, right ventricular hypertrophy (RVH), large perimembranous ventricular septal defect (VSD), and right ventricular outflow tract obstruction (RVOTO). About 20% of patients with TOF have PA at the infundibular or valvar level, which results in severe right ventricular outflow tract obstruction. PA means that the pulmonary valve is closed and not developed. When PA occurs, blood can not flow through the pulmonary arteries to the lungs. Instead, the child is dependent on a patent ductus arteriosus (PDA) or multiple systemic collateral vessels (MAPCAs) to deliver blood to the lungs for oxygenation. These MAPCAs usually arise from the de- scending aorta and subclavian arteries. Commonly, the pulmonary arteries are abnormal, with hypoplastic (small and underdeveloped) central and branch pulmonary arteries and/ or non-confluent central pulmonary arteries. -

Review of Systems Health History Sheet Patient: ______DOB: ______Age: ______Gender: M / F

603 28 1/4 Road Grand Junction, CO 81506 (970) 263-2600 Review of Systems Health History Sheet Patient: _________________ DOB: ____________ Age: ______ Gender: M / F Please mark any symptoms you are experiencing that are related to your complaint today: Allergic/ Immunologic Ears/Nose/Mouth/Throat Genitourinary Men Only Frequent Sneezing Bleeding Gums Pain with Urinating Pain/Lump in Testicle Hives Difficulty Hearing Blood in Urine Penile Itching, Itching Dizziness Difficulty Urinating Burning or Discharge Runny Nose Dry Mouth Incomplete Emptying Problems Stopping or Sinus Pressure Ear Pain Urinary Frequency Starting Urine Stream Cardiovascular Frequent Infections Loss of Urinary Control Waking to Urinate at Chest Pressure/Pain Frequent Nosebleeds Hematologic / Lymphatic Night Chest Pain on Exertion Hoarseness Easy Bruising / Bleeding Sexual Problems / Irregular Heart Beats Mouth Breathing Swollen Glands Concerns Lightheaded Mouth Ulcers Integumentary (Skin) History of Sexually Swelling (Edema) Nose/Sinus Problems Changes in Moles Transmitted Diseases Shortness of Breath Ringing in Ears Dry Skin Women Only When Lying Down Endocrine Eczema Bleeding Between Shortness of Breath Increased Thirst / Growth / Lesions Periods When Walking Urination Itching Heavy Periods Constitutional Heat/Cold Intolerance Jaundice (Yellow Extreme Menstrual Pain Exercise Intolerance Gastrointestinal Skin or Eyes) Vaginal Itching, Fatigue Abdominal Pain Rash Burning or Discharge Fever Black / Tarry Stool Respiratory Waking to Urinate at Weight Gain (___lbs) Blood -

Drug Eruptions- When to Worry

3/17/2017 Drug reactions: Drug Eruptions‐ When to Worry 3 things you need to know 1. Type of drug reaction 2. Statistics: – Which drugs are most likely to cause that type of Lindy P. Fox, MD reaction? Associate Professor 3. Timing: Director, Hospital Consultation Service – How long after the drug started did the reaction Department of Dermatology University of California, San Francisco begin? [email protected] I have no conflicts of interest to disclose 1 Drug Eruptions: Common Causes of Cutaneous Drug Degrees of Severity Eruptions • Antibiotics Simple Complex • NSAIDs Morbilliform drug eruption Drug hypersensitivity reaction Stevens-Johnson syndrome •Sulfa (SJS) Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) • Allopurinol Minimal systemic symptoms Systemic involvement • Anticonvulsants Potentially life threatening 1 3/17/2017 Morbilliform (Simple) Drug Eruption Morbilliform (Simple) Drug Eruption Per the drug chart, the most likely culprit is: Per the drug chart, the most likely culprit is: Day Day Day ‐> ‐8 ‐7 ‐6 ‐5 ‐4 ‐3 ‐2 ‐1 0 1 Day ‐> ‐8 ‐7 ‐6 ‐5 ‐4 ‐3 ‐2 ‐1 0 1 A vancomycin x x x x A vancomycin x x x x B metronidazole x x B metronidazole x x C ceftriaxone x x x C ceftriaxone x x x D norepinephrine x x x D norepinephrine x x x E omeprazole x x x x E omeprazole x x x x F SQ heparin x x x x F SQ heparin x x x x trimethoprim/ trimethoprim/ G xxxxxxx G xxxxxxx sulfamethoxazole sulfamethoxazole Admit day Rash onset Admit day Rash onset Morbilliform (Simple) Drug Eruption Drug Induced Hypersensitivity Syndrome • Begins 5‐10 days after drug started -

Isolated Single Umbilical Artery: Need for Specialist Fetal Echocardiography?

Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol (2010) Published online in Wiley Online Library (wileyonlinelibrary.com). DOI: 10.1002/uog.7711 Isolated single umbilical artery: need for specialist fetal echocardiography? D. DEFIGUEIREDO, T. DAGKLIS, V. ZIDERE, L. ALLAN and K. H. NICOLAIDES Harris Birthright Research Centre for Fetal Medicine, King’s College Hospital Medical School, London, UK KEYWORDS: cardiac defect; fetal echocardiography; prenatal diagnosis; single umbilical artery; ultrasound ABSTRACT was 33.6% (Table 1)3–15. Consequently, the prenatal diagnosis of SUA should motivate the sonographer to Objective To examine the association between single undertake a systematic and detailed examination of the umbilical artery (SUA) and cardiac defects and to fetal anatomy for the diagnosis or exclusion of associated determine whether patients with SUA require specialist defects. In the reported series of SUA, the prevalence of fetal echocardiography. cardiac defects was 11.4%, but it is not stated whether Methods Incidence and type of cardiac defects were these were isolated or whether they were associated with 3–15 determined in fetuses with SUA detected at routine other, more easily detectable, defects (Table 1) . second-trimester ultrasound examination. In this study we examined the association between SUA and cardiac defects with the aim of determining Results A routine second-trimester scan was performed whether patients with SUA require specialist fetal in 46 272 singleton pregnancies at a median gestation of echocardiography. 22 (range, 18–25) weeks and an SUA was diagnosed in 246 (0.5%). Cardiac defects were diagnosed in 16 (6.5%) of these cases, including 10 (4.3%) in a subgroup of METHODS 233 with no other defects and in six (46.2%) of the 13 with multiple defects. -

Transcatheter Device Closure of Atrial Septal Defect in Dextrocardia with Situs Inversus Totalis

Case Report Nepalese Heart Journal 2019; Vol 16(1), 51-53 Transcatheter device closure of atrial septal defect in dextrocardia with situs inversus totalis Kiran Prasad Acharya1, Chandra Mani Adhikari1, Aarjan Khanal2, Sachin Dhungel1, Amrit Bogati1, Manish Shrestha3, Deewakar Sharma1 1 Department of Cardiology, Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal 2 Department of Internal Medicine, Kathmandu Medical College, Kathmandu,Nepal 3 Department of Pediatric Cardiology, Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre, Kathmandu, Nepal Corresponding Author: Chandra Mani Adhikari Department of Cardiology Shahid Gangalal National Heart Centre Kathmandu, Nepal Email: [email protected] Cite this article as: Acharya K P, Adhikari C M, Khanal A, et al. Transcatheter device closure of atrial septal defect in dextrocardia with situs inversus totalis. Nepalese Heart Journal 2019; Vol 16(1), 51-53 Received date: 17th February 2019 Accepted date: 16th April 2019 Abstract Only few cases of Device closure of atrial septal defect in dextrocardia with situs inversus totalis has been reported previously. We present a case of a 36 years old male, who had secundum type of atrial septal defect in dextrocardia with situs inversus totalis. ASD device closure was successfully done. However, we encountered few technical difficulties in this case which are discussed in this case review. Keywords: atrial septal defect; dextrocardia; transcatheter device closure, DOI: https://doi.org/10.3126/njh.v16i1.23901 Introduction There are only two case reported of closure of secundum An atrial septal defect (ASD) is an opening in the atrial ASD associated in patients with dextrocardia and situs inversus septum, excluding a patent foramen ovale.1 ASD is a common totalis. -

Tetralogy of Fallot.” These Podcasts Are Designed to Give Medical Students an Overview of Key Topics in Pediatrics

PedsCases Podcast Scripts This is a text version of a podcast from Pedscases.com on “Tetralogy of Fallot.” These podcasts are designed to give medical students an overview of key topics in pediatrics. The audio versions are accessible on iTunes or at www.pedcases.com/podcasts. Tetralogy of Fallot Developed by Katie Girgulis, Dr. Andrew Mackie, and Dr. Karen Forbes for PedsCases.com. April 14, 2017 Introduction Hello, my name is Katie Girgulis and I am a medical student at the University of Alberta. This podcast was developed with the help of Dr. Andrew Mackie and Dr. Karen Forbes. Dr. Mackie is a pediatric cardiologist at the Stollery Children’s Hospital, and Dr. Forbes is a pediatrician and medical educator at the Stollery Children’s Hospital. This podcast is about the cardiac condition Tetralogy of Fallot (ToF). For teaching on the general approach to pediatric heart murmurs, please check out the ‘Evaluation of a Heart Murmur’ podcast on Pedscases.com. Slide 2 Learning Objectives By the end of this podcast, the learner will be able to: 1) Recognize the clinical presentations of ToF 2) Describe the four anatomical characteristics of ToF 3) Describe the pathophysiology of the murmur in ToF 4) Formulate initial steps when ToF is suspected 5) Delineate the treatment of hypercyanotic episodes 6) Summarize the definitive treatment for ToF Slide 3 Case – Baby Josh Let’s start with a clinical case: You are working with Dr. Smith, a family physician, during your family medicine rotation. Josh is a 4-month-old infant who is here for a well-baby check.