Why Is Knowledge Creation and Transfer So Difficult in Large Multinational Corporations? Evidence from the Business History Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Full Papers At

Market Leader Quarter 4, 2010 www.warc.com Editorial: Barriers to innovation Judie Lannon We have looked at innovation a number of times, but in the cover story of this issue John Kearon takes a heretical approach – arguing that marketing science itself and the centralisation of marketing expertise in large organisations may be at the root of the lack of genuine new category innovation. The theme of the ponderous, risk-averse corporation which is excellent at nurturing what it has (and, indeed, is the reason it got big) but not so hot at creating genuinely new category brands is familiar territory. But Kearon's evidence is compelling. And challenging. However, another light at the end of this particular tunnel may lie with the work being done with online communities and other forms of co- creation. Done bravely and imaginatively, this dispenses with the cliché of consumers not knowing what they want by going straight to the more creative thinker-users (often fanatics who, theoretically, could be just as inventive as any company research and development department or engineer). This approach is radical in itself and has the potential to encourage large companies to behave like the more adventurous startups. But, as has been examined in several articles in previous issues of Market Leader, the problem never lies in having the idea – that's the easy bit. Getting it through mazes and silos of the organisational hierarchy is the difficult bit. But the search for barriers to innovative thinking goes much wider than merely the size and structure of the organisation. -

Table of Contents

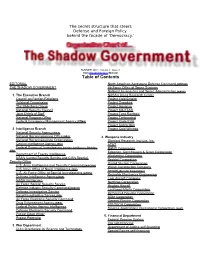

The secret structure that steers Defense and Foreign Policy behind the facade of 'Democracy.' SUMMER 2001 - Volume 1, Issue 3 from TrueDemocracy Website Table of Contents EDITORIAL North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) THE SHADOW GOVERNMENT Air Force Office of Space Systems National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 1. The Executive Branch NASA's Ames Research Center Council on Foreign Relations Project Cold Empire Trilateral Commission Project Snowbird The Bilderberg Group Project Aquarius National Security Council Project MILSTAR Joint Chiefs of Staff Project Tacit Rainbow National Program Office Project Timberwind Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Project Code EVA Project Cobra Mist 2. Intelligence Branch Project Cold Witness National Security Agency (NSA) National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) 4. Weapons Industry National Reconnaissance Organization Stanford Research Institute, Inc. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) AT&T Federal Bureau of Investigation , Counter Intelligence Division RAND Corporation (FBI) Edgerton, Germhausen & Greer Corporation Department of Energy Intelligence Wackenhut Corporation NSA's Central Security Service and CIA's Special Bechtel Corporation Security Office United Nuclear Corporation U.S. Army Intelligence and Security Command (INSCOM) Walsh Construction Company U.S. Navy Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) Aerojet (Genstar Corporation) U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI) Reynolds Electronics Engineering Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) Lear Aircraft Company NASA Intelligence Northrop Corporation Air Force Special Security Service Hughes Aircraft Defense Industry Security Command (DISCO) Lockheed-Maritn Corporation Defense Investigative Service McDonnell-Douglas Corporation Naval Investigative Service (NIS) BDM Corporation Air Force Electronic Security Command General Electric Corporation Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) PSI-TECH Corporation Federal Police Agency Intelligence Science Applications International Corporation (SAIC) Defense Electronic Security Command Project Deep Water 5. -

1998 Annual Review and Summary Financial Statement

Annual Review1998 Annual Review 1998 And Summary Financial Statement English Version in Guilders And SummaryFinancialStatement English Version inGuilders English Version U Unilever N.V. Unilever PLC meeting everyday needs of people everywhere Weena 455, PO Box 760 PO Box 68, Unilever House 3000 DK Rotterdam Blackfriars, London EC4P 4BQ Telephone +31 (0)10 217 4000 Telephone +44 (0)171 822 5252 Telefax +31 (0)10 217 4798 Telefax +44 (0)171 822 5951 Produced by: Unilever Corporate Relations Department Design: The Partners Photography: Mike Abrahams, Peter Jordan, Barry Lewis, Tom Main, Bill Prentice & Andrew Ward Editorial Consultants: Wardour Communications U Typesetting & print: Westerham Press Limited, St Ives plc Unilever‘s Corporate Purpose Our purpose in Unilever is to meet the everyday needs of people everywhere – to anticipate the aspirations of our consumers and customers and to respond creatively and competitively with branded products and services which raise the quality of life. Our deep roots in local cultures and markets around the world are our unparalleled inheritance and the foundation for our future growth. We will bring our wealth of knowledge and international expertise to the service of local consumers – a truly multi-local multinational. ENGLISH GUILDERS Our long-term success requires a total commitment to exceptional standards of performance and productivity, to working together effectively and to a willingness to embrace new ideas and learn continuously. We believe that to succeed requires the highest standards of corporate behaviour towards our employees, consumers and the societies and world in which we live. This is Unilever’s road to sustainable, profitable growth for our business and long-term value creation for our shareholders and employees. -

Annual Report 2011-12

ANNUAL REPORT 2011-12 Creating a better future every day HINDUSTAN UNILEVER LIMITED Registered Office: Unilever House, B D Sawant Marg, Chakala, Andheri East, Mumbai 400099 Hindustan www.hul.co.in U nilever nilever L imited Annual Report 2011-12 AwARDS AND FELICITATIONS WINNING WITH BRANDS AND WINNING THROUGH CONTINUOUS SUSTAINABILITY OUR MISSION INNOVATION IMPROVEMENT HUL has won the Asian Centre for Six of our brands (Lux, Lifebuoy, Closeup, HUL was awarded the FMCG Supply Corporate Governance and Sustainability Fair & Lovely, Clinic Plus and Sunsilk) Chain Excellence Award at the 5th Awards in the category ‘Company with the featured in Top 15 list in Brand Equity’s Express, Logistics & Supply Chain Awards Best CSR and Sustainability Practices.’ WE WORK TO CREATE A BETTER FUTURE Most Trusted Brands Survey. endorsed by The Economic Times along Our instant Tea Factory, Etah bagged the with the Business India Group. EVERY DAY. Hindustan Unilever Limited (HUL) was second prize in tea category for Energy awarded the CNBC AWAAZ Storyboard Doomdooma factory won the Gold Award Conservation from Ministry of Power, We help people feel good, look good and get more out Consumer Awards 2011 in three in the Process Sector, Large Business Govt. of India. categories. category at The Economic Times India HUL won the prestigious ‘Golden Peacock Manufacturing Excellence Awards 2011. of life with brands and services that are good for them • FMCG Company of the Year Global Award for Corporate Social and good for others. • The Most Consumer Conscious Responsibility’ for the year 2011. Company of the Year WINNING WITH PEOPLE HUL’s Andheri campus received • The Digital Marketer of the Year We will inspire people to take small, everyday actions HUL was ranked the No.1 Employer of certification of LEED India Gold in ‘New HUL won the ‘Golden Peacock Innovative Choice for students in the annual Nielsen Construction’ category, by Indian Green that can add up to a big difference for the world. -

Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020

k Kosher Nosh Guide Summer 2020 For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk CONTENTS 5 USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS 5 EXPLANATION OF KASHRUT SYMBOLS 5 PROBLEMATIC E NUMBERS 6 BISCUITS 6 BREAD 7 CHOCOLATE & SWEET SPREADS 7 CONFECTIONERY 18 CRACKERS, RICE & CORN CAKES 18 CRISPS & SNACKS 20 DESSERTS 21 ENERGY & PROTEIN SNACKS 22 ENERGY DRINKS 23 FRUIT SNACKS 24 HOT CHOCOLATE & MALTED DRINKS 24 ICE CREAM CONES & WAFERS 25 ICE CREAMS, LOLLIES & SORBET 29 MILK SHAKES & MIXES 30 NUTS & SEEDS 31 PEANUT BUTTER & MARMITE 31 POPCORN 31 SNACK BARS 34 SOFT DRINKS 42 SUGAR FREE CONFECTIONERY 43 SYRUPS & TOPPINGS 43 YOGHURT DRINKS 44 YOGHURTS & DAIRY DESSERTS The information in this guide is only applicable to products made for the UK market. All details are correct at the time of going to press but are subject to change. For the latest information check www.isitkosher.uk. Sign up for email alerts and updates on www.kosher.org.uk or join Facebook KLBD Kosher Direct. No assumptions should be made about the kosher status of products not listed, even if others in the range are approved or certified. It is preferable, whenever possible, to buy products made under Rabbinical supervision. WARNING: The designation ‘Parev’ does not guarantee that a product is suitable for those with dairy or lactose intolerance. WARNING: The ‘Nut Free’ symbol is displayed next to a product based on information from manufacturers. The KLBD takes no responsibility for this designation. You are advised to check the allergen information on each product. k GUESS WHAT'S IN YOUR FOOD k USING THE PRODUCT LISTINGS Hi Noshers! PRODUCTS WHICH ARE KLBD CERTIFIED Even in these difficult times, and perhaps now more than ever, Like many kashrut authorities around the world, the KLBD uses the American we need our Nosh! kosher logo system. -

Vernieuwend Wassen R&D in Vlaardingen En De Detergents-Business Van Unilever

Vernieuwend wassen: Vernieuwend Vernieuwend wassen Vernieuwend wassen R&D in Vlaardingen en de detergents-business van Unilever R&D in Vlaardingen en de detergents-business Met de vorming van Unilever in 1930 ontstond één van de grootste zeep- en margarine- R&D in Vlaardingen en de producenten ter wereld. Zeep en margarine vormen overigens een logische combinatie, van Unilever beide bedrijfstakken werkten immers met dezelfde grondstoffen: oliën en vetten. In dit cahier staat de Research & Development van Unilever op het terrein van wasmiddelen Ton van Helvoort, Mila Davids en Harry Lintsen centraal. Waar het bij de R&D van voedingsmiddelen vaak om stapsgewijze zogeheten onzichtbare innovaties gaat, wordt de markt van wasmiddelen juist gekenmerkt door een reeks van radicale innovaties. De meest cruciale nieuwigheid was het op de markt komen van de synthetische wasmiddelen. Niet langer vormden plantaardige of dierlijke grondstoffen de basis, de bouwstenen werden voortaan geleverd door de aardolie- industrie. detergents Om de positie op de markt te kunnen vasthouden stond aan wasmiddelen gerelateerd onderzoek bij de Unilever laboratoria in Port Sunlight (Engeland) en Vlaardingen hoog -business van Unilever op de agenda. Innovaties vonden zowel plaats in de processing als in het verbeteren van de wasmiddelen. De auteurs laten zien hoe de onderzoekers van Unilever zich richtten op onderwerpen zoals de werking van oppervlakactieve stoffen, de toepassing van enzymen, fosfaatverontreiniging, het bleken bij lage temperatuur en de bijbehorende vermindering van het energieverbruik alsmede de bereiding van compacte poeders. De analyse van de R&D-inspanningen maakt duidelijk hoe allerlei ontwikkelingen met elkaar samenhangen; elke ‘innovatieve’ aanpassing kan gevolgen hebben elders in het netwerk. -

Product Origin Pcs/Case Cases/Pallet Self-Life Price Exw

Product Origin Pcs/Case Cases/Pallet Self-life Price Exw (€) CORNETTO CHOCOLATE 120ml Portugal 40 99 540 1,11 € CORNETTO MORANGO/STRAWBERRY 120ml Portugal 40 99 450 1,11 € CORNETTO TROPICAL 120ml Italia 24 162 540 1,32 € CORNETTO CLASSIC GLUTEN FREE 125ml Italia 24 162 540 1,11 € CORNETTO GO SANDWICH 110ml Lithuania 33 128 730 0,88 € CORNETTO CHOC'N BALL 160ml Sweden 20 126 540 1,47 € CORNETTO COOKIE N DREAM 120ml Italia 24 162 540 1,32 € MAGNUM AMENDOAS/ALMOND 120ml Portugal 20 228 730 1,32 € MAGNUM BRANCO/WHITE 120ml Portugal 20 228 730 1,32 € MAGNUM CLASSIC 120ml Portugal 20 228 730 1,32 € MAGNUM SANDWICH 140ml Sweden 20 231 730 1,18 € MAGNUM DOUBLE CARAMEL 88ml Polonia 20 228 730 1,47 € MAGNUM CARAMEL & NUTS 64ml Italia 30 308 730 0,91 e MAGNUM WHITE CHOCOLATE and COOKIES 90ml Alemannia 20 228 730 1,47 € Product Size Origin Pcs/Case Cases/Pallet Self-life Price Exw (€) 100ml Hollande 12 375 540 1,80 € CHOCOLATE FUDGE BROWNIE 500ml Hollande 8 180 540 5,96 € 100ml Hollande 12 375 540 1,80 € STRAWBERRY CHEESECAKE CUP 500ml Hollande 8 180 540 5,96 € 100ml Hollande 12 375 540 1,80 € PEANUT BUTTER CUP 500ml Hollande 8 180 540 5,96 € 100ml Hollande 12 375 540 1,80 € COOKIE DOUGH CUP 500ml Hollande 8 180 540 5,96 € 100ml Hollande 12 375 540 1,80 € CARAMEL CHEW CHEW 100ml 500ml Hollande 8 180 540 5,96 € VANILLA PECAN 100ml Hollande 12 375 540 1,80 € WICH COOKIE DOUGH 100ml Greece 20 192 540 1,84 € WICH COOKIE CHOC FUDGE BROWNIE 100ml Greece 20 192 540 1,84 € SOFA SO NICE 500ml Hollande 8 180 540 5,95 € Product Origin Pcs/Case Cases/Pallet -

Wall's Refrigeration Solutions 0161 888 1466 Available on Request

PRINTED ON 100% WALLS RECYCLED STREET JOURN’AL PAPER WE’RE PASSIONATE ABOUT ICE CREAM ICE CREAM HAS COMMITMENT REALLY GREAT TO SOURCING CHOCOLATE CASH MARGINS1 P13 ETHICALLY P23 2020 EDITION WALLSICECREAM.COM Welcome to an exciting new Ice Cream Season for 2020. We are so Every Day is an proud to be representing the best Ice Cream brands in the UK which cover a massive 71% of the total UK Handheld singles ice cream Ice Cream Day 2 market . This refl ects how much our consumers love our brands in the UK by Wall’s Ice Cream Team and enjoy eating our Ice Cream. As an important impulse purchase, Ice Cream is able to Ice Cream o ers retailers great cash margins, better than generate huge footfall potential. Therefore, as a business, any other snacking options. we are committed to helping our partners unlock the sales In 2020, we have bigger and bolder plans for our amazing new opportunities the category presents. We are investing products and cabinets all coordinated by our experienced signifi cantly in attracting shoppers through out of home fi eld operation team. With the new Ice Cream season kicking communication as well as providing retailers with the right o on New Year’s Day, we know that your customers won’t tools in store to help maximise growth potential. want to spend a single day without a Wall’s Ice Cream in 2020. FULL STORY: P20 1: Based on selling at the recommended retail price: accounts for promotional plan & illustrative electricity prices. Based on MAT to 17.12.17 selling 9 impulse and 3 take home ice creams per day, not including cabinet cost. -

What's New for 1 Unilever Ice Cream 1 What's

Un ilever Wha t’s New Wha t’s New Ice Cream :@1 for :@1 for :@1 Peanut Butter Cookies Love ‘n’ Dream Unilever has 55* tal share of the To m* Impulse Ice Crea *Source: Nielsen, Total Impulse Market, Singles Ice Cream, Unit Sales, MAT, 27th December 2014 the Why Stock Wall’s Ice Cream, me to Welco ream Ice C The Impulse Ice Cream Market all’s 1 * W re :@ Brochu is worth £127 million! New product innovation continues to create he UK l Un in t a ilever i and t s the br UK's excitement and encourage ream r o e c ve T ic ic nile big n icon ong! U f gest ice cr new consumers to try ice n a str o eam g s bee goin m a l e ’s h stil n & a * cream; in 2014 £12.7 all ’re Be r ma n W we m, e ufact u a u rs and agn r rer a M h ye as C million of total ice cream 90 uch s er s s . for ov urite more e * o d c v n % a a I e f o sales were from NPD! d ler inclu , So r s er e nd ist e ra w s b T r tto, l e u orn eam u s, C e cr t y’ ic p Jerr more c ell a s m s, f seller r all I he best answe u 15% * tock t here to n 55 s e a o help you why we’r 015. -

Download Download

Transnational Corporate Ties: A Synopsis of Theories and Empirical Findings Michael Nollert introduction or sociologists and analysts of the world economy, it is certainly a matter of Ffact that transnational corporations are by no means isolated actors in an economic “war of all against all” (Th omas Hobbes). Rather, transnational cor- porations are frequently members of corporate networks, often of global reach. Although the literature on globalization emphasizes the increasing economic power of these networks and postulates the formation of a transnational capital- ist class, there is still a lack of empirical fi ndings. Th is article starts with a review of theoretical perspectives (resource dependence, social capital, coordination of markets, fi nancial hegemony, class hegemony, inner circle, and transnational capitalist class) which focuses on the functions and structures of corporate inter- locks at the national and the transnational level. Th e subsequent section off ers a synopsis of studies concerning transnational corporate networks. Th ese analyses of corporate ties (interlocking directorates, fi nancial participations and policy group affi liations) suggest the emergence of transnational economic elites whose members, however, have not lost their national identity. In the fi nal section, the theoretical perspectives will be assessed and some prospects are sketched out. Finally, it will be argued that the disintegration of the world society, which is considerably driven by rent-seeking corporate networks, can only be restrained if a potential global regulatory agency will be anchored in a post-Washington consensus. abstract: In general, corporations are not isolated pirical studies concerning transnational cor- actors in an economic “war of all against all” porate networks. -

Adams Adkinson Aeschlimann Aisslinger Akkermann

BUSCAPRONTA www.buscapronta.com ARQUIVO 27 DE PESQUISAS GENEALÓGICAS 189 PÁGINAS – MÉDIA DE 60.800 SOBRENOMES/OCORRÊNCIA Para pesquisar, utilize a ferramenta EDITAR/LOCALIZAR do WORD. A cada vez que você clicar ENTER e aparecer o sobrenome pesquisado GRIFADO (FUNDO PRETO) corresponderá um endereço Internet correspondente que foi pesquisado por nossa equipe. Ao solicitar seus endereços de acesso Internet, informe o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO, o número do ARQUIVO BUSCAPRONTA DIV ou BUSCAPRONTA GEN correspondente e o número de vezes em que encontrou o SOBRENOME PESQUISADO. Número eventualmente existente à direita do sobrenome (e na mesma linha) indica número de pessoas com aquele sobrenome cujas informações genealógicas são apresentadas. O valor de cada endereço Internet solicitado está em nosso site www.buscapronta.com . Para dados especificamente de registros gerais pesquise nos arquivos BUSCAPRONTA DIV. ATENÇÃO: Quando pesquisar em nossos arquivos, ao digitar o sobrenome procurado, faça- o, sempre que julgar necessário, COM E SEM os acentos agudo, grave, circunflexo, crase, til e trema. Sobrenomes com (ç) cedilha, digite também somente com (c) ou com dois esses (ss). Sobrenomes com dois esses (ss), digite com somente um esse (s) e com (ç). (ZZ) digite, também (Z) e vice-versa. (LL) digite, também (L) e vice-versa. Van Wolfgang – pesquise Wolfgang (faça o mesmo com outros complementos: Van der, De la etc) Sobrenomes compostos ( Mendes Caldeira) pesquise separadamente: MENDES e depois CALDEIRA. Tendo dificuldade com caracter Ø HAMMERSHØY – pesquise HAMMERSH HØJBJERG – pesquise JBJERG BUSCAPRONTA não reproduz dados genealógicos das pessoas, sendo necessário acessar os documentos Internet correspondentes para obter tais dados e informações. DESEJAMOS PLENO SUCESSO EM SUA PESQUISA. -

WO 2012/139943 A3 18 October 2012 (18.10.2012) P O P C T

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2012/139943 A3 18 October 2012 (18.10.2012) P O P C T (51) International Patent Classification: Quarry Road East, Bebington, Wirral Merseyside CH63 A61K 8/19 (2006.01) A61K 8/39 (2006.01) 3JW (GB). WIRE, Stephen, Lee [GB/GB]; Unilever R&D A61K 8/27 (2006.01) A61Q 5/06 (2006.01) Port Sunlight, Quarry Road East, Bebington, Wirral Mer A61K 8/368 (2006.01) A61Q 5/10 (2006.01) seyside CH63 3JW (GB). A61K 8/37 (2006.01) (74) Agent: TANSLEY, Sally, Elizabeth; Unilever PLC, Uni (21) International Application Number: lever Patent Group, Colworth House, Sharnbrook, Bedford PCT/EP2012/056152 Bedfordshire MK44 1LQ (GB). (22) International Filing Date: (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every 4 April 2012 (04.04.2012) kind of national protection available): AE, AG, AL, AM, AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BR, BW, BY, BZ, (25) Filing Language: English CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DK, DM, DO, (26) Publication Language: English DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IS, JP, KE, KG, KM, KN, KP, KR, (30) Priority Data: KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LT, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, 11162233.8 13 April 201 1 (13.04.201 1) EP MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, (71) Applicant (for AE, AG, AU, BB, BH, BW, BZ, CA, CY, OM, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SC, SD, EG, GB, GD, GH, GM, IE, IL, IN, KE, KN, LC, LK, LS, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, MT, MW, MY, NA, NG, NZ, OM, PG, QA, RW, SC, SD, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW.