Helmet Heads

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Terminology of Armor in Old French

1 A 1 e n-MlS|^^^PP?; The Terminology Of Amor In Old French. THE TERMINOLOGY OF ARMOR IN OLD FRENCH BY OTHO WILLIAM ALLEN A. B. University of Illinois, 1915 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ROMANCE LANGUAGES IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1916 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL CO oo ]J1^J % I 9 I ^ I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPER- VISION BY WtMc^j I^M^. „ ENTITLED ^h... *If?&3!£^^^ ^1 ^^Sh^o-^/ o>h, "^Y^t^C^/ BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF. hu^Ur /] CUjfo In Charge of Thesis 1 Head of Department Recommendation concurred in :* Committee on Final Examination* Required for doctor's degree but not for master's. .343139 LHUC CONTENTS Bibliography i Introduction 1 Glossary 8 Corrigenda — 79 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 http://archive.org/details/terminologyofarmOOalle i BIBLIOGRAPHY I. Descriptive Works on Armor: Boeheim, Wendelin. Handbuch der Waffenkunde. Leipzig, 1890, Quicherat, J, Histoire du costume en France, Paris, 1875* Schultz, Alwin. Das hofische Leben zur Zeit der Minnesinger. Two volumes. Leipzig, 1889. Demmin, August. Die Kriegswaffen in ihren geschicht lichen Ent wicklungen von den altesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart. Vierte Auflage. Leipzig, 1893. Ffoulkes, Charles. Armour and Weapons. Oxford, 1909. Gautier, Leon. La Chevalerie. Viollet-le-Duc • Dictionnaire raisonne' du mobilier frangais. Six volumes. Paris, 1874. Volumes V and VI. Ashdown, Charles Henry. Arms and Armour. New York. Ffoulkes, Charles. The Armourer and his Craft. -

WFRP Equipment

Name Damage Group Traits Range (Yards) Reload Buckler d10+SB-2 Parrying Balanced, Defensive, Pummelling Dagger d10+SB-2 Ordinary Balanced, Puncturing Flail d10+SB+2 Flail 2h, Impact, Unwieldy, Fast Knuckleduster d10+SB-2 Ordinary Pummelling Great Weapon d10+SB+2 Two-Handed 2h, Impact Zweihander d10+SB+1 Two-Handed 2h, Defensive, Impact, Stances: Half-sword, Mordschlag Longsword d10+SB Two-Handed 2h, Impact, Defensive, Stance: Hand Weapon, Half-sword, Mordschlag Polearm d10+SB+1 Two-Handed 2h, Impact, Fast, Stance: Half-sword Hand Weapon d10+SB Ordinary None Improvised d10+SB-2 Ordinary None Lance d10+SB+1 Cavalry Fast, Impact, Special Main Gauche d10+SB-2 Parrying Balanced, Defensive, Puncturing Morningstar d10+SB Flail Impact, Unwieldy, Fast Staff d10+SB Ordinary 2h, Defensive, Impact, Pummelling Rapier d10+SB-1 Fencing Fast, Precise (2) Shield d10+SB-2 Ordinary Defensive (Melee & Ranged), Pummelling Spear d10+SB-1 Ordinary Fast, Stance: 2h Spear 2h d10+SB+1 2h, Fast Sword-Breaker d10+SB-2 Parrying Balanced, Special Unarmed d10+SB-3 Ordinary Special Stances Halfsword d10+SB 2h, Defensive, Armour Piercing (2), Precise (1) Mordschlag d10+SB 2h, Impact, Pummelling, Armour Piercing (1) Bola d10+1 Entangling Snare 8/16 Half Bow d10+3 Ordinary 2h 24/48 Half Crossbow d10+4 Ordinary 2h 30/60 Full Crossbow Pistol d10+2 Crossbow None 8/16 Full Elfbow d10+3 Longbow Armour Piercing, 2h 36/72 Half Improvised d10+SB-4 Ordinary None 6/- Half Javelin d10+SB-1 Ordinary None 8/16 Half Lasso n/a Entangling Snare, 2h 8/- Half Longbow d10+3 Longbow Armour -

Hau 009 Eng.Pdf

Magazine devoted to military history, uniformology and war equipment since the Ancient Era until the 20th century Publishing Director: Bruno Mugnai Redational Staff: Anthony J. Jones; Andrew Tzavaras; Luca S. Cristini. Collaborators: András K. Molnár; Ciro Paoletti; Riccardo Caimmi; Paolo Coturri; Adriana Vannini, Chun L. Wang; Mario Venturi; Christian Monteleone; Andrea Rossi. Cover: Sonia Zanat; Silvia Orso. * * * Scientific Committee: John Gooch; Peter H. Wilson; Bruce Vandervort; Frederick C. Schneid; Tóth Ferenc; Chris Stockings; Guilherme d'Andrea Frota; Krisztof Kubiak; Jean Nicolas Corvisier; Erwin A. Schmidl; Franco Cardini. #9–2016 PUBLISHER’S NOTE None of images or text of our book may be reproduced in any format without the expressed written permission of publisher. The publisher remains to disposition of the possible having right for all the doubtful sources images or not identifies. Each issue Euro 3,90; Subscription to 11 issues Euro 40,00. Subscriptions through the Magazine website: www.historyanduniforms.com or through Soldiershop ,by Luca S. Cristini, via Padre Davide 8, Zanica (BG). Original illustrations are on sale. Please contact: [email protected] © 2016 Bruno Mugnai HaU_009_ENG - Web Magazine - ISSN not required. Contents: Warriors and Warfare of the Han Dynasty (part three) Chun L. Wang Four Centuries of Italian Armours (12 th -15 th century) (part two) Mario Venturi French Ensigns of the Late-Renaissance (part one) Aldo Ziggioto and Andrea Rossi The Venetian Army and Navy in the Ottoman War of 1684-99 (part nine) Bruno Mugnai The Austrian Light Infantry, 1792-1801 (part two) Paolo Coturri and Bruno Mugnai Forgotten Fronts of WWI: the Balkans, 1916 (part two) Oleg Airapetov Book Reviews The Best on the Net Dear Friend, Dear Reader! The Issue 9 is an important turning point for our magazine. -

The Classic Suit of Armor

Project Number: JLS 0048 The Classic Suit of Armor An Interactive Qualifying Project Report Submitted to the Faculty of the WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Science by _________________ Justin Mattern _________________ Gregory Labonte _________________ Christopher Parker _________________ William Aust _________________ Katrina Van de Berg Date: March 3, 2005 Approved By: ______________________ Jeffery L. Forgeng, Advisor 1 Table of Contents ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................................. 5 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 6 RESEARCH ON ARMOR: ......................................................................................................................... 9 ARMOR MANUFACTURING ......................................................................................................................... 9 Armor and the Context of Production ................................................................................................... 9 Metallurgy ........................................................................................................................................... 12 Shaping Techniques ............................................................................................................................ 15 Armor Decoration -

Armour & Weapons in the Middle Ages

& I, Ube 1bome Hnttquarg Series ARMOUR AND WEAPONS IN THE MIDDLE AGES t Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 https://archive.org/details/armourweaponsinmashd PREFACE There are outward and visible signs that interest in armour and arms, so far from abating, is steadily growing. When- ever any examples of ancient military equipment appear n in sale-rooms a keen and eager throng of buyers invariably | assembles ; while one has only to note the earnest and ' critical visitors to museums at the present time, and to compare them with the apathetic onlookers of a few years J ago, to realize that the new generation has awakened to j j the lure of a fascinating study. Assuredly where once a single person evinced a taste for studying armour many | now are deeply interested. t The books dealing with the subject are unfortunately ' either obsolete, like the works of Meyrick, Planche, Fos- broke, Stothard, and others who flourished during the last L century, or, if recent, are beyond the means of many would-be students. My own book British and Foreign Arms and Armour is now out of print, while the monographs of I Charles ffoulkes, the Rev. Charles Boutell, and | Mr Mr Starkie Gardner are the only reasonably priced volumes j now obtainable. It seemed, therefore, desirable to issue a small handbook which, while not professing in the least to be comprehensive, would contain sufficient matter to give the young student, y the ' man in the street,' and the large and increasing number of persons who take an intelligent interest in the past just j that broad outline which would enable them to understand more exhaustive tomes upon armour and weapons, and 5 ARMOUR AND WEAPONS possibly also to satisfy those who merely wish to glean sufficient information to enable them to discern inac- curacies in brasses, effigies, etc., where the mind of the medieval workman—at all times a subject of the greatest interest—has led him to introduce features which were not in his originals, or details which he could not possibly have seen. -

Raffle Items

Raffle Items Lots 1 Sparkling Soul Necklace – Draen 1-1 2 Velium Etched Stone Mace – Draen 1-2 3 Finely Crafted Velium Ring – Draen 1-3 4 Ketchata Koro Mis – Draen 1-4 5 Lumberjack’s Cap – Draen 1-5 6 Dusty Bloodstained Gloves – Draen 1-6 7 Shadowbone Earring – Draen 1-7 8 Stein of Moggok – Draen 1-8 9 Small crafted gaultlet – Draen 2-1 10 dark rust boots – Draen 2-2 11 small crafted vambraces – Draen 2-3 12 13 cloak of the ice bear – Draen 2-5 14 Wu’s Fighting Gauntlets – Draen 2-6 15 Skull Shaped Barbute – Draen 2-7 16 Staff of Writhing – Draen 2-8 17 Dagger of Dropping – Draen 3-1 18 Dark Mail Gauntlets – Draen 3-2 19 Polished Granite Tomahawk – Draen 3-3 20 Shiny Brass Shield – Draen 3-4 21 Adamantite Band – Draen 3-5 22 Tizmak Tunic – Draen 3-6 23 9dex 9CHR veil – Draen 3-7 24 Foreman’s Skull cap – Draen 3-8 25 Skull shaped barbute – Draen 4-1 26 Gnomeskin Boots – Draen 4-2 26 Gnome Skin Cap – Calid 8-1 26 Gnome Skin Neck – Calid 8-2 26 Gnome Skin Tunic – Calid 8-3 26 Gnome Skin Wristband – Calid 8-4 27 Spiderfang Choker – Draen 4-3 28 Sarnak Ceremonial Sword – Draen 4-4 29 Sarnak Pitchatka – Draen 4-5 30 Blade of Passage – Draen 4-6 31 Blackened Iron Girdle – Draen 4-7 32 Chill Dagger – Draen 4-8 33 Embalmer’s Skinning Knife – Draen 5-1 34 Opalling Earring – Draen 5-2 34 Opalline Earring – Draen 5-6 35 bloodstained Mantle – Draen 5-3 36 Jagged Band – Draen 5-4 36 Jagged band – Calid 7-3 37 kobold hide boots – Draen 5-7 38 dragoon dirk – Draen 5-8 39 Glowing Wooden Crook – Draen 6-1 40 blackened Iron Arms – Draen 6-2 41 3DEX 3AGI -

CAS Hanwei 25Th Anniversary Catalog!

CAS25th Anniversary Hanwei Catalog Welcome to the CAS Hanwei 25th Anniversary Catalog! 2010 marks the 25th anniversary of CAS’s inception and to celebrate our quarter-century Hanwei has excelled in producing the Silver Anniversary Shinto, a superlative Limited Edition (very limited!) version of the first Katana that Hanwei ever made for CAS. The original Shinto enabled many sword enthusiasts to afford a purpose-built cutting sword for the first time, introducing many enthusiasts to the sport of Tameshigiri, and the Silver Anniversary Shinto, featured on the covers and Page 14 of this catalog remains true to the basic design but features silver-plated fittings, advanced blade metallurgy and a stand unique to this sword. Also new to this catalog are the swords of two traditionally warring Ninja clans (the Kouga and Iga, Page 38) that depart from the typical plain-Jane Ninja styling and will be welcomed by Ninjaphiles every- where. The new Tactical Wak (Page 37) is a modern version of the traditional Wakizashi, intended for serious outdoor use and protection – it will see a lot of use in the backwoods. Reenactors will be excited about the new Hand-and-a-Half sword (the Practical Bastard Sword, Page 71), with its upgraded steel, great handling and new user-friendly scabbard styling. The number of martial arts practitioners enjoying cutting with Chinese-style swords is growing very rapidly and so we had Scott Rodell, author and teacher of this discipline, design the first purpose-built cutting sword (the Cutting Jian, Page 50) for these enthusiasts. Several mid-2009 introductions are now also included in our full catalog for the first time. -

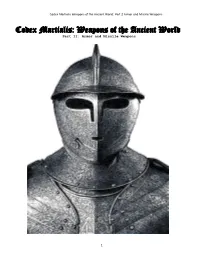

Codex Martialis: Weapons of the Ancient World

Cod ex Mart ial is Weapo ns o f t he An cie nt Wor ld : Par t 2 Arm or a nd M issile Weapo ns Codex Martialis : Weapons of the A ncient World Par t II : Ar mo r an d Mi ss il e We ap on s 1 188.6.65.233 Cod ex Mart ial is Weapo ns o f t he An cie nt Wor ld : Par t 2 Arm or a nd M issile Weapo ns Codex Martialis: Weapons of the Ancient World Part 2 , Ar mor an d Missile Weapo ns Versi on 1 .6 4 Codex Ma rtia lis Copyr ig ht 2 00 8, 2 0 09 , 20 1 0, 2 01 1, 20 1 2,20 13 J ean He nri Cha nd ler 0Credits Codex Ma rtia lis W eapons of th e An ci ent Wo rld : Jean He nri Chandler Art ists: Jean He nri Cha nd ler , Reyna rd R ochon , Ram on Esteve z Proofr ead ers: Mi chael Cur l Special Thanks to: Fabri ce C og not of De Tail le et d 'Esto c for ad vice , suppor t and sporad ic fa ct-che cki ng Ian P lum b for h osting th e Co de x Martia lis we bsite an d co n tinu in g to prov id e a dvice an d suppo rt wit ho ut which I nev e r w oul d have publish ed anyt hi ng i ndepe nd ent ly. -

Goods and Gear

KENZER AND COMPANY PRESENTS A PLAYER’S ADVANTAGE™ GUIDE: GOODSGOODS ANDAND GEAR:GEAR: THE ULTIMATE ADVENTURER'S GUIDE by Mark Plemmons and Brian Jelke CREDITS HackMaster Conversions: Steve Johansson, Cover Illustrations: Keith DeCesare, Lars Grant-West Don Morgan, D. M. Zwerg Interior Illustrations: Caleb Cleveland, Storn Cook, Additional Contributors: Jeff Abar, Jolly Blackburn, Keith DeCesare, Thomas Denmark, Marcio Fiorito, Lloyd Brown III, Eric Engelhard, Ed Greenwood, Mitch Foust, Brendon and Brian Fraim, Richard Jensen, Steve Johansson, David Kenzer, Ferdinand Gertes, Lars Grant-West, Noah Kolman, Jamie LaFountain, James Mishler, David Esbri Molinas, CD Regan, Kevin Wasden. Don Morgan, Travis Stout, John Terra, Playtesters: Mark Billanie, Jim Bruni, Anne Canava, Phil Thompson, Paul Wade-Williams, D.M. Zwerg Doug Click, Gigi Epps, D. Andrew Ferguson, Editors: Eric Engelhard, Brian Jelke, Steve Johansson, Sarah Ferguson, Charles Finnell, Donovan Grimwood, David Kenzer, Don Morgan, Mark Plemmons Daniel Haslam, Mark Howe, Patrick Hulley, Project Manager: Brian Jelke Steven Lambert, Mark Lane, Jeff McAuley, Alan Moore, Production Manager: Steve Johansson Mark Prater, Anthony Roberson, Daniel Scothorne, Art Coordinator: Mark Plemmons David Sink Jr., Mark Sizer, Joe Wallace, John Williams Behind the Scenes: Jennifer Kenzer and John Wright. © Copyright 2004 Kenzer and Company. All Rights Reserved. Questions, Comments, Product Orders? Printed in China Phone: (847) 540-0029 Kenzer & Company Fax: (847) 540-8065 email: [email protected] 511 W. Greenwood Visit our website: Waukegan, IL 60087 www.kenzerco.com This book is protected under international treaties and copyright laws of the PUBLISHER’S NOTE: United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced, without This is a work of fiction. -

HELMETS and BODY ARMOR in MODERN WARFARE DEAN Presented to The

HELMETS AND BODY ARMOR IN MODERN WARFARE DEAN Presented to the University of Toronto by the Yale University Press in recognition ofthe sacrifices made by Canada for the cause of Liberty and Civilization in theWorld War and to commemorate the part played in the struggle by the eight thousand Yale gradu- ates in the service of the Allied Governments 1914-1918 HELMETS AND BODY ARMOR IN MODERN WARFARE THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART PUBLICATION OF THE COMMITTEE ON EDUCATION HENRY S. PRITCHETT, PH.D., LL.D., CHAIRMAN HELMETS AND BODY ARMOR IN MODERN WARFARE. BY BASHFORD DEAN, PH.D. British Standard British (Variant) German Standard American Model, No. 5A American Model, No. 2A Belgian, Visored HELMETS, 1916-1918. STATS French Standard American Model, No. 4 American Model, No. 10 American Model, "Liberty Bell' American Model, No. 8 French Dunand Model EXPERIMENTAL MODELS THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART HELMETS AND BODY ARMOR IN MODERN WARFARE nv^ BY BASHFORD DEAN, PH.D. CURATOR OF ARMOR, METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART FORMERLY MAJOR OF ORDNANCE, U. S. A., IN CHARGE OF ARMOR UNIT, EQUIPMENT SECTION, ENGINEERING DIVISION, WASHINGTON FORMERLY CHAIRMAN OF THE COMMITTEE ON HELMETS AND BODY ARMOR, ENGINEERING DIVISION OF THE NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL "Effort should be continued towards the development of a satis- factory form of personal body armor." General Pershing, 1917. 3 u . a r NEW HAVEN: YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON HUMPHREY MILFORD OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS MDCCCCXX u 825 DM- COPYRIGHT, 1920, BY YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS. PREFACE f~ tf ""^HE present book aims to consider the virtues and failings of hel- $ mets and body armor in modern warfare. -

Helmets and Body Armor in Modern Warfare

/ THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART HELMETS AND BODY ARMOR IN MODERN WARFARE BY / BASHFORD DEAN, Ph.D. ir CURATOR OF ARMOR, METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART FORMERLY MAJOR OF ORDNANCE, U. S. A., IN CHARGE OF ARMOR UNIT, EQUIPMENT SECTION, ENGINEERING DIVISION, WASHINGTON FORMERLY CHAIRMAN OF THE COMMITTEE ON HELMETS AND BODY ARMOR, ENGINEERING DIVISION OF THE NATIONAL RESEARCH COUNCIL "Effort should be continued towards the development of a satis- factory form of personal body armor."— General Pershing, 1917. NEW HAVEN: YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON HUiVIPHREY MILFORD • OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS MDCCCCXX Qy/ykAJL 2- 1^ *o' COPYRIGHT, 1920, BY / YALE UNIVERSITY PRESS. ^ ©CI.A576300 SEP -/-jb^G British Standard British (Variant) German Standard American Model, No. 2A Belgian, Visored HELMETS, 1916-1918. STANDAF French Standard American Model, No. 4 American Model, No. 10 American Model, "Liberty Bell" American Model, No. 8 French Dunand Model ND EXPERIMENTAL MODELS : PREFACE present book aims to consider the virtues and failings of hel- THEmets and body armor in modern warfare. To this end it brings together materials collected from all accessible sources; it shows the kinds of armor which each nation has been using in the Great War, what practical tests they will resist, of what materials they are made, and what they have done in saving life and limb. As an introduction to these headings there has now been added a section which deals with ancient armor; this enables us to contrast the old with the new and to indicate, in clearer perspective, what degree of success the latest armor may achieve in its special field. -

Hau 008 Eng (1).Pdf

Magazine devoted to military history, uniformology and war equipment since the Ancient Era until the 20th century Publishing Director: Bruno Mugnai Redational Staff: Anthony J. Jones; Andrew Tzavaras; Luca S. Cristini Collaborators: András K. Molnár; Ciro Paoletti; Riccardo Caimmi; Paolo Coturri; Adriana Vannini; Chun L. Wang; Mario Venturi; Chris Flaherty; Oleg Airapetov; Massimo Predonzani Cover: Sonia Zanat; Silvia Orso. * * * Scientific Committee: John Gooch; Peter H. Wilson; Bruce Vandervort; Frederick C. Schneid; Tóth Ferenc; Chris Stockings; Guilherme d'Andrea Frota; Krisztof Kubiak; Jean Nicolas Corvisier; Erwin A. Schmidl; Franco Cardini. #8–2016 PUBLISHER’S NOTE None of images or text of our book may be reproduced in any format without the expressed written permission of publisher. The publisher remains to disposition of the possible having right for all the doubtful sources images or not identifies. Each issue Euro 3,90; Subscription to 11 issues Euro 40,00 . Subscriptions through the Magazine website: www.historyanduniforms.com or through Soldiershop ,by Luca S. Cristini, via Padre Davide 8, Zanica (BG). Original illustrations are on sale. Please contact: [email protected] © 2016 Bruno Mugnai HaU_008 - Web Magazine - ISSN not required. Contents: Warriors and Warfare of the Han Dynasty (part two) Chun L. Wang Four Centuries of Italian Armours (12 th -15 th century) (part two) Mario Venturi The Venetian Army and Navy in the Ottoman War of 1684-99 (part nine) Bruno Mugnai The Austrian Light Infantry, 1792-1800 (part one) Paolo Coturri and Bruno Mugnai Origins of the French Zouaves Uniforms Chris Flaherty Forgotten Fronts of WWI: the Balkans, 1916 (part one) Oleg Airapetov Book Reviews The Best on the Net Dear Reader, Dear Friend: A pause due to a sudden change of program resulted in a new index for Issue 7, while now a hacker attack caused a new delay for completing issue 8.