V Harlc^Hr^ and Davhi Li

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MEDIEVAL ARMOR Over Time

The development of MEDIEVAL ARMOR over time WORCESTER ART MUSEUM ARMS & ARMOR PRESENTATION SLIDE 2 The Arms & Armor Collection Mr. Higgins, 1914.146 In 2014, the Worcester Art Museum acquired the John Woodman Higgins Collection of Arms and Armor, the second largest collection of its kind in the United States. John Woodman Higgins was a Worcester-born industrialist who owned Worcester Pressed Steel. He purchased objects for the collection between the 1920s and 1950s. WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 3 Introduction to Armor 1994.300 This German engraving on paper from the 1500s shows the classic image of a knight fully dressed in a suit of armor. Literature from the Middle Ages (or “Medieval,” i.e., the 5th through 15th centuries) was full of stories featuring knights—like those of King Arthur and his Knights of the Round Table, or the popular tale of Saint George who slayed a dragon to rescue a princess. WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 4 Introduction to Armor However, knights of the early Middle Ages did not wear full suits of armor. Those suits, along with romantic ideas and images of knights, developed over time. The image on the left, painted in the mid 1300s, shows Saint George the dragon slayer wearing only some pieces of armor. The carving on the right, created around 1485, shows Saint George wearing a full suit of armor. 1927.19.4 2014.1 WORCESTER ART MUSEUM / 55 SALISBURY STREET / WORCESTER, MA 01609 / 508.799.4406 / worcesterart.org SLIDE 5 Mail Armor 2014.842.2 The first type of armor worn to protect soldiers was mail armor, commonly known as chainmail. -

EVA Checklist

JSC-48023 EVA Checklist Mission Operations Directorate EVA, Robotics, and Crew Systems Operations Division Generic, Rev H March 4, 2005 NOTE For STS-114 and subsequent (chronological) flights per current schedule. National Aeronautics and Space Administration Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center Houston, Texas Verify this is the correct version for the pending operation (training, simulation or flight). Electronic copies of FDF books are available. URL: http://mod.jsc.nasa.gov/do3/FDF/index.html Incorporates the following: 482#: EVA-1529 EVA-1555 EVA-1564 MULTI-1693 EVA-1530 EVA-1556 EVA-1565 MULTI-1694 EVA-1543 EVA-1557 EVA-1566 EVA-1544A EVA-1558 EVA-1567 EVA-1546 EVA-1559 EVA-1568 EVA-1551 EVA-1560 EVA-1569 EVA-1552 EVA-1561 EVA-1570(P) EVA-1553 EVA-1562 EVA-1554 EVA-1563 (P) – Partially implemented in this publication AREAS OF TECHNICAL RESPONSIBILITY Book Manager DX35/P. Boehm 281-483-5447 Task Procedures DX32/K. Shook 281-483-4474 ii EVA/ALL/GEN H EVA CHECKLIST LIST OF EFFECTIVE PAGES GENERIC 12/07/87 PCN-6 11/10/06 PCN-13 02/15/08 REV H 03/04/05 PCN-7 02/20/07 PCN-14 04/15/08 PCN-1 04/08/05 PCN-8 05/22/07 PCN-15 08/28/08 PCN-2 06/10/05 PCN-9 06/15/07 PCN-16 01/16/09 PCN-3 08/01/05 PCN-10 07/18/07 PCN-17 04/07/09 PCN-4 06/12/06 PCN-11 09/28/07 PCN-5 08/17/06 PCN-12 12/14/07 Sign Off ...................... -

Stab Resistant Body Armour

IAN HORSFALL STAB RESISTANT BODY ARMOUR COLLEGE OF DEFENCE TECHNOLOGY SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF PhD CRANFIELD UNIVERSITY ENGINEERING SYSTEMS DEPARTMENT SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF PhD 1999-2000 IAN HORSFALL STAB RESISTANT BODY ARMOUR SUPERVISOR DR M. R. EDWARDS MARCH 2000 ©Cranfield University, 2000. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT There is now a widely accepted need for stab resistant body armour for the police in the UK. However, very little research has been done on knife resistant systems and the penetration mechanics of sharp projectiles are poorly understood. This thesis explores the general background to knife attack and defence with a particular emphasis on the penetration mechanics of edged weapons. The energy and velocity that can be achieved in stabbing actions has been determined for a number of sample populations. The energy dissipated against the target was shown to be primarily the combined kinetic energy of the knife and the arm of the attacker. The compliance between the hand and the knife was shown to significantly affect the pattern of energy delivery. Flexibility and the resulting compliance of the armour was shown to have a significant effect upon the absorption of this kinetic energy. The ability of a knife to penetrate a variety of targets was studied using an instrumented drop tower. It was found that the penetration process consisted of three stages, indentation, perforation and further penetration as the knife slides through the target. Analysis of the indentation process shows that for slimmer indenters, as represented by knives, frictional forces dominate, and indentation depth becomes dependent upon the coefficient of friction between indenter and sample. -

Saint Demetrios of Thessaloniki

Master of Philosophy Faculty of Arts University of Glasgow Saint Demetrios of Thessaloniki By Lena Kousouros Christie's Education London Master's Programme September 2000 ProQuest Number: 13818861 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818861 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 ^ v r r ARV- ^ [2,5 2 . 0 A b stract This thesis intends to explore the various forms the representations of Saint Demetrios took, in Thessaloniki and throughout Byzantium. The study of the image of Saint Demetrios is an endeavour of considerable length, consisting of numerous aspects. A constant issue running throughout the body of the project is the function of Saint Demetrios as patron Saint of Thessaloniki and his ever present protective image. The first paper of the thesis will focus on the transformation of the Saint’s image from courtly figure to military warrior. Links between the main text concerning Saint Demetrios, The Miracles, and the artefacts will be made and the transformation of his image will be observed on a multitude of media. -

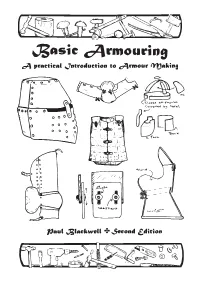

Basic-Armouring-2Of4.Pdf

Chapter 8 — Padding Because you need to build your armour around your padding you need to know how to make it first! Gamberson This supplies basic padding under the body armour and something to hang your arm armour off. Some people rely on their gamberson (with a few minor additions such as a kidney belt) as their torso protection. This gives them excellent mobility at the expense of protection. If you are learning to fight, as well as armour, you are liable to get hit a lot so body armour might not be a bad idea—your choice! Making a gamberson is a sewing job; go get a needle and thread or borrow a sewing machine. The material you make it from should be relatively tough (it’s going to take a beating), adsorbent (you are going to sweat into it), colour fast (unless you want to start a new fashion in oddly coloured flesh) and washable (see sweating above). Period gambersons were made from multiple layers of cloth stitched together or padded with raw wool or similar material, modern ones often use an internal fill of cotton or polyester batting to achieve the same look with less weight. A descrip- tion of an arming doublet of the 15th century is “a dowbelet of ffustean (a type of heavy woollen broad cloth) lyned with satene cutte full of hoolis”. A heavy outer material, such as canvas or calico, is therefore appropriate with a softer lining next to the skin. For extra ventilation you can add buttonholes down the quilting seams. -

ICCD Thesaurus Per La Definizione Dei Reperti Archeologici Agg2020-21

MINISTERO DELLA CULTURA ISTITUTO CENTRALE PER IL CATALOGO E LA DOCUMENTAZIONE Strumenti terminologici Thesaurus per la definizione dei reperti archeologici mobili (applicazione nella scheda RA - Reperti archeologici, versione 3.00) aggiornamento 2020 - 21 Coordinamento: Maria Letizia Mancinelli (ICCD - Servizio per la qualità degli standard catalografici) Collaborazione tecnico-scientifica (ricerche e stesura del vocabolario, aggiornamenti, 2009 - 2014): Maria Teresa Natale Collaborazione tecnico-scientifica (aggiornamento 2020-21): Eugenia Imperatori Premessa L’esposizione dei contenuti del thesaurus è organizzata sulla base della seguente tabella: LIVELLI GERARCHICI PREVISTI NEL THESAURUS SONO UTILIZZATI PER VALORIZZARE CAMPI DIVERSI DEL TRACCIATO DELLA SCHEDA RA 3.00, paragrafo OG-OGGETTO (vedere di seguito le istruzioni specifiche) LIVELLI DA UTILIZZARE PER LA COMPILAZIONE DEL CAMPO LIVELLI DA UTILIZZARE PER LA COMPILAZIONE DEL SOTTOCAMPO CLS Categoria - Classe e produzione OGTD - Definizione ATTRIBUTI DEL TERMINE INSERITO IN UNO DEI LIVELLI 1-5 Per la compilazione del campo CLS vanno selezionate le definizioni gerarchicamente relazionate al termine e alle sue eventuali specifiche scelti dai successivi livelli 4 e 5 del thesaurus (si rinvia in proposito alle istruzioni per l’utilizzo del vocabolario aperto per il campo CLS della scheda RA, pubblicate sul sito ICCD) LIVELLO 1 LIVELLO 2 LIVELLO 3 LIVELLO 4 LIVELLO 5 CATEGORIA CATEGORIA CATEGORIA TERMINE IMMAGINE TERMINE TERMINE PIU’ SPECIFICO NOTA D’AMBITO I LIVELLO II LIVELLO III LIVELLO -

Fashion,Costume,And Culture

FCC_TP_V4_930 3/5/04 3:59 PM Page 1 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages FCC_TP_V4_930 3/5/04 3:59 PM Page 3 Fashion, Costume, and Culture Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Volume 4: Modern World Part I: 19004 – 1945 SARA PENDERGAST AND TOM PENDERGAST SARAH HERMSEN, Project Editor Fashion, Costume, and Culture: Clothing, Headwear, Body Decorations, and Footwear through the Ages Sara Pendergast and Tom Pendergast Project Editor Imaging and Multimedia Composition Sarah Hermsen Dean Dauphinais, Dave Oblender Evi Seoud Editorial Product Design Manufacturing Lawrence W. Baker Kate Scheible Rita Wimberley Permissions Shalice Shah-Caldwell, Ann Taylor ©2004 by U•X•L. U•X•L is an imprint of For permission to use material from Picture Archive/CORBIS, the Library of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of this product, submit your request via Congress, AP/Wide World Photos; large Thomson Learning, Inc. the Web at http://www.gale-edit.com/ photo, Public Domain. Volume 4, from permissions, or you may download our top to bottom, © Austrian Archives/ U•X•L® is a registered trademark used Permissions Request form and submit CORBIS, AP/Wide World Photos, © Kelly herein under license. Thomson your request by fax or mail to: A. Quin; large photo, AP/Wide World Learning™ is a trademark used herein Permissions Department Photos. Volume 5, from top to bottom, under license. The Gale Group, Inc. Susan D. Rock, AP/Wide World Photos, 27500 Drake Rd. © Ken Settle; large photo, AP/Wide For more information, contact: Farmington Hills, MI 48331-3535 World Photos. -

Archaeologist in the Archive. a Turning Point in the Study of Late-Medieval Helmets in Western Pomerania

FASCICULI ARCHAEOLOGIAE HISTORICAE FASC. XXXIII, PL ISSN 0860-0007 DOI 10.23858/FAH33.2020.011 ANDRZEJ JANOWSKI* ARCHAEOLOGIST IN THE ARCHIVE. A TURNING POINT IN THE STUDY OF LATE-MEDIEVAL HELMETS IN WESTERN POMERANIA Abstract: The article discusses three late-medieval head protectors from Western Pomerania, forgotten by Polish scholars after World War II. The first one is the great helm known as the Topfhelm from Dargen, the second, a bascinet with visor from Leszczyn and the last one, the jousting sallet from the collection of Szczecin masons. Knowledge about those helms is highly significant for studies of late-medieval armour in Western Pomerania. Keywords: Western Pomerania, medieval armour, great helm, bascinet, jousting sallet Received: 15.04.2020 Revised: 29.04.2020 Accepted: 27.07.2020 Citation: Janowski A. 2020. Archaeologist in the Archive. A Turning Point in the Study of Late-medieval Helmets in Western Pomerania. “Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae” 33, 167-174, DOI 10.23858/FAH33.2020.011 Elements of armour either in whole or in large The Great Helm from Dargen fragments belong to unique finds in the archaeology The first piece of head protection discussed here of the Middle Ages. Each more or less complete find is a find which must be known to all armour special- is considered a sensation. Western Pomeranian finds ists (Fig. 1). It is one of the best preserved and oldest are no different in this respect; new finds of this type great helms, dating back to the middle-second half of are few and far between.1 The study of primary sourc- the 13th century. -

The Terminology of Armor in Old French

1 A 1 e n-MlS|^^^PP?; The Terminology Of Amor In Old French. THE TERMINOLOGY OF ARMOR IN OLD FRENCH BY OTHO WILLIAM ALLEN A. B. University of Illinois, 1915 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN ROMANCE LANGUAGES IN THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS 1916 UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS THE GRADUATE SCHOOL CO oo ]J1^J % I 9 I ^ I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPER- VISION BY WtMc^j I^M^. „ ENTITLED ^h... *If?&3!£^^^ ^1 ^^Sh^o-^/ o>h, "^Y^t^C^/ BE ACCEPTED AS FULFILLING THIS PART OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF. hu^Ur /] CUjfo In Charge of Thesis 1 Head of Department Recommendation concurred in :* Committee on Final Examination* Required for doctor's degree but not for master's. .343139 LHUC CONTENTS Bibliography i Introduction 1 Glossary 8 Corrigenda — 79 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2014 http://archive.org/details/terminologyofarmOOalle i BIBLIOGRAPHY I. Descriptive Works on Armor: Boeheim, Wendelin. Handbuch der Waffenkunde. Leipzig, 1890, Quicherat, J, Histoire du costume en France, Paris, 1875* Schultz, Alwin. Das hofische Leben zur Zeit der Minnesinger. Two volumes. Leipzig, 1889. Demmin, August. Die Kriegswaffen in ihren geschicht lichen Ent wicklungen von den altesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart. Vierte Auflage. Leipzig, 1893. Ffoulkes, Charles. Armour and Weapons. Oxford, 1909. Gautier, Leon. La Chevalerie. Viollet-le-Duc • Dictionnaire raisonne' du mobilier frangais. Six volumes. Paris, 1874. Volumes V and VI. Ashdown, Charles Henry. Arms and Armour. New York. Ffoulkes, Charles. The Armourer and his Craft. -

Ballistic Helmets – Their Design, Materials, and Performance Against Traumatic Brain Injury

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln US Army Research U.S. Department of Defense 2013 Ballistic helmets – Their design, materials, and performance against traumatic brain injury S.G. Kulkarni Texas A&M University, [email protected] X.-L. Gao University of Texas at Dallas, [email protected] S.E. Horner U.S. Army, Fort Belvoir J.Q. Zheng U.S. Army, Fort Belvoir N.V. David Universiti Teknologi MARA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usarmyresearch Kulkarni, S.G.; Gao, X.-L.; Horner, S.E.; Zheng, J.Q.; and David, N.V., "Ballistic helmets – Their design, materials, and performance against traumatic brain injury" (2013). US Army Research. 201. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usarmyresearch/201 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Defense at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in US Army Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Composite Structures 101 (2013) 313–331 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Composite Structures journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/compstruct Review Ballistic helmets – Their design, materials, and performance against traumatic brain injury ⇑ S.G. Kulkarni a, X.-L. Gao b, , S.E. Horner c, J.Q. Zheng c, N.V. David d a Department of Mechanical Engineering, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, United States b Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Texas at Dallas, 800 West Campbell Road, Richardson, TX 75080-3021, United States c Program Executive Office – SOLDIER, U.S. -

Armour Manual Mark II Ze

Basic Armouring—A Practical Introduction to Armour Making, Second Edition By Paul Blackwell Publishing History March 1986: First Edition March 2002: Second Edition Copyright © 2002 Paul Blackwell. This document may be copied and printed for personal use. It may not be distributed for profit in whole or part, or modified in any way. Electronic copies may be made for personal use. Electronic copies may not be published. The right of Paul Blackwell to be identified as the Author and Illustrator of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The latest electronic version of this book may be obtained from: http://www.brighthelm.org/ Ye Small Print—Cautionary Note and Disclaimer Combat re-enactment in any form carries an element of risk (hey they used to do this for real!) Even making armour can be hazardous, if you drop a hammer on your foot, cut yourself on a sharp piece of metal or do something even more disastrous! It must be pointed out, therefore, that if you partake in silly hobbies such as these you do so at your own risk! The advice and information in this booklet is given in good faith (most having been tried out by the author) however as I have no control over what you do, or how you do it, I can accept no liability for injury suffered by yourself or others while making or using armour. Ye Nice Note Having said all that I’ll just add that I’ve been playing for ages and am still in one piece and having fun. -

England's Armor

ENGLAND’S ARMOR: HENRY VIII’S ARMOR AND HIS WARS by James Nobukichi Ito A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Art in Art History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2014 ©COPYRIGHT by James Nobukichi Ito 2014 All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION I dedicate this Master’s Thesis to Donald La Rocca, Dr. Todd Larkin, and to Vaughan Judge for their support and guidance in helping me achieve my graduate goals. To Dede Taylor who gave me the Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin Of Arms and Men, which got me seriously interested in the topic of arms and armor as a Master’s Thesis. To my fellow graduate students; Kate Cottingham, Chelsea Higgins, Jackie Meade, and Jesine Munson. To the School of Art office staff. I dedicate the success of graduate school to my wife Stephanie, who tolerated me being away from home for these last two years researching and writing my thesis and for bringing our son Jefferson into this world while I was in graduate school. You are my greatest supporter, Stephanie. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have grown as a scholar and as a person in these last two years of graduate school and I have the art history faculty to thank for that. Todd Larkin was my committee chair and he has been my most involved mentor who pushed me to conduct active research and question all evidence of my findings to weave out any doubt that what I discovered was reliable information. He has also been an example to me as a scholar who is enthusiastic about his work and teaches in a way that keeps the class attentive and alive.