Basic-Armouring-2Of4.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 0 Menu Roman Armour Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries

Roman Armour Chain Mail Armour Transitional Armour Plate Mail Armour Milanese Armour Gothic Armour Maximilian Armour Greenwich Armour Armour Diagrams Page 0 Menu Roman Armour Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries. Replaced old chain mail armour. Made up of dozens of small metal plates, and held together by leather laces. Lorica Segmentata Page 1 100AD - 400AD Worn by Roman Officers as protection for the lower legs and knees. Attached to legs by leather straps. Roman Greaves Page 1 ?BC - 400AD Used by Roman Legionaries. Handle is located behind the metal boss, which is in the centre of the shield. The boss protected the legionaries hand. Made from several wooden planks stuck together. Could be red or blue. Roman Shield Page 1 100AD - 400AD Worn by Roman Legionaries. Includes cheek pieces and neck protection. Iron helmet replaced old bronze helmet. Plume made of Hoarse hair. Roman Helmet Page 1 100AD - 400AD Soldier on left is wearing old chain mail and bronze helmet. Soldiers on right wear newer iron helmets and Lorica Segmentata. All soldiers carry shields and gladias’. Roman Legionaries Page 1 400BC - 400AD Used as primary weapon by most Roman soldiers. Was used as a thrusting weapon rather than a slashing weapon Roman Gladias Page 1 400BC - 400AD Worn by Roman Officers. Decorations depict muscles of the body. Made out of a single sheet of metal, and beaten while still hot into shape Roman Cuiruss Page 1 ?- 400AD Chain Mail Armour Page 2 400BC - 1600AD Worn by Vikings, Normans, Saxons and most other West European civilizations of the time. -

Computational Modeling of Primary Blast Effects on the Human Brain

Computational Modeling of Primary Blast Effects on the Human Brain by Michelle K. Nyein S.B., Chemistry, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2004) J.D., Harvard University (2007) S.M., Aeronautics and Astronautics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (2010) Submitted to the Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Aeronautics and Astronautics at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2013 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2013. All rights reserved. Author............................................. ...................................... Department of Aeronautics and Astronautics March 4, 2013 Certified by.......................................... ..................................... Ra´ul Radovitzky Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics Thesis Supervisor Certified by.......................................... ..................................... Dava J. Newman Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics Certified by.......................................... ..................................... Laurence R. Young Apollo Program Professor of Aeronautics and Astronautics Certified by.......................................... ..................................... Simona Socrate Principal Research Scientist, Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies Certified by.......................................... ..................................... David F. Moore Attending Neurologist, Baylor University Medical Center Accepted by........................................ -

Interim Report on the Preservation Virginia Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia

2007–2010 Interim Report on the Preservation Virginia Excavations at Jamestown, Virginia Contributing Authors: David Givens, William M. Kelso, Jamie May, Mary Anna Richardson, Daniel Schmidt, & Beverly Straube William M. Kelso Beverly Straube Daniel Schmidt Editors March 2012 Structure 177 (Well) Structure 176 Structure 189 Soldier’s Pits Structure 175 Structure 183 Structure 172 Structure 187 1607 Burial Ground Structure 180 West Bulwark Ditch Solitary Burials Marketplace Structure 185 Churchyard (Cellar/Well) Excavations Prehistoric Test Ditches 28 & 29 Structure 179 Fence 2&3 (Storehouse) Ludwell Burial Structure 184 Pit 25 Slot Trenches Outlines of James Fort South Church Excavations Structure 165 Structure 160 East Bulwark Ditch 2 2 Graphics and maps by David Givens and Jamie May Design and production by David Givens Photography by Michael Lavin and Mary Anna Richardson ©2012 by Preservation Virginia and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. All rights reserved, including the right to produce this report or portions thereof in any form. 2 2 Acknowledgements (2007–2010) The Jamestown Rediscovery team, directed by Dr. William this period, namely Juliana Harding, Christian Hager, and Kelso, continued archaeological excavations at the James Matthew Balazik. Thank you to the Colonial Williamsburg Fort site from 2007–2010. The following list highlights Foundation architectural historians who have analyzed the some of the many individuals who contributed to the project fort buildings with us: Cary Carson, Willie Graham, Carl during these -

Archaeologist in the Archive. a Turning Point in the Study of Late-Medieval Helmets in Western Pomerania

FASCICULI ARCHAEOLOGIAE HISTORICAE FASC. XXXIII, PL ISSN 0860-0007 DOI 10.23858/FAH33.2020.011 ANDRZEJ JANOWSKI* ARCHAEOLOGIST IN THE ARCHIVE. A TURNING POINT IN THE STUDY OF LATE-MEDIEVAL HELMETS IN WESTERN POMERANIA Abstract: The article discusses three late-medieval head protectors from Western Pomerania, forgotten by Polish scholars after World War II. The first one is the great helm known as the Topfhelm from Dargen, the second, a bascinet with visor from Leszczyn and the last one, the jousting sallet from the collection of Szczecin masons. Knowledge about those helms is highly significant for studies of late-medieval armour in Western Pomerania. Keywords: Western Pomerania, medieval armour, great helm, bascinet, jousting sallet Received: 15.04.2020 Revised: 29.04.2020 Accepted: 27.07.2020 Citation: Janowski A. 2020. Archaeologist in the Archive. A Turning Point in the Study of Late-medieval Helmets in Western Pomerania. “Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae” 33, 167-174, DOI 10.23858/FAH33.2020.011 Elements of armour either in whole or in large The Great Helm from Dargen fragments belong to unique finds in the archaeology The first piece of head protection discussed here of the Middle Ages. Each more or less complete find is a find which must be known to all armour special- is considered a sensation. Western Pomeranian finds ists (Fig. 1). It is one of the best preserved and oldest are no different in this respect; new finds of this type great helms, dating back to the middle-second half of are few and far between.1 The study of primary sourc- the 13th century. -

Ballistic Helmets – Their Design, Materials, and Performance Against Traumatic Brain Injury

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln US Army Research U.S. Department of Defense 2013 Ballistic helmets – Their design, materials, and performance against traumatic brain injury S.G. Kulkarni Texas A&M University, [email protected] X.-L. Gao University of Texas at Dallas, [email protected] S.E. Horner U.S. Army, Fort Belvoir J.Q. Zheng U.S. Army, Fort Belvoir N.V. David Universiti Teknologi MARA Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usarmyresearch Kulkarni, S.G.; Gao, X.-L.; Horner, S.E.; Zheng, J.Q.; and David, N.V., "Ballistic helmets – Their design, materials, and performance against traumatic brain injury" (2013). US Army Research. 201. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usarmyresearch/201 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Defense at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in US Army Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Composite Structures 101 (2013) 313–331 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Composite Structures journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/compstruct Review Ballistic helmets – Their design, materials, and performance against traumatic brain injury ⇑ S.G. Kulkarni a, X.-L. Gao b, , S.E. Horner c, J.Q. Zheng c, N.V. David d a Department of Mechanical Engineering, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX 77843, United States b Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Texas at Dallas, 800 West Campbell Road, Richardson, TX 75080-3021, United States c Program Executive Office – SOLDIER, U.S. -

Heroic Armor of the Italian Renaissnace

30. MASKS GARNITURE OF CHARLES V Filippo Negroli and his brothers Milan, dated 1539 Steel, gold, and silver Wt. 31 lb. 3 oz. (14,490 g) RealArmeria, Patrimonio Nacional, Madrid (A 139) he Masks Garniture occupies a special place in the Negroli Toeuvre as the largest surviving armor ensemble signed by Filippo N egroli and the only example of his work to specify unequivocally the participation of two or more of his broth ers. The armor's appellation, "de los mascarones," derives from the grotesque masks that figure prominently in its dec oration, and it was coined by Valencia de Don Juan (1898) to distinguish it from the many other harnesses of Charles V in the Real Armeria. Indeed, for Valencia, none of the emperor's numerous richly embellished armors could match this one for the beauty of its decoration. As the term "garniture" implies, the harness possesses a number of exchange and reinforcing pieces that allow it to be employed, with several variations, for mounted use in the field as well as on foot. The exhibited harness is composed of the following ele ments: a burgonet with hinged cheekpieces and a separate, detachable buffe to close the face opening; a breastplate with two downward-overlapping waist lames and a single skirt lame supporting tassets (upper thigh defenses) of seven lames each that are divisible between the second and third lames; a backplate with two waist lames and a single culet (rump) lame; asymmetrical pauldrons (shoulder defenses) made in one with vambraces (arm defenses) and having large couters open on the inside of the elbows; articulated cuisses (lower thigh defenses) with poleyns (knees); and half greaves open on the inside of the leg. -

Armour Manual Mark II Ze

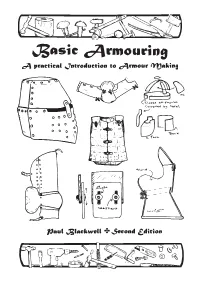

Basic Armouring—A Practical Introduction to Armour Making, Second Edition By Paul Blackwell Publishing History March 1986: First Edition March 2002: Second Edition Copyright © 2002 Paul Blackwell. This document may be copied and printed for personal use. It may not be distributed for profit in whole or part, or modified in any way. Electronic copies may be made for personal use. Electronic copies may not be published. The right of Paul Blackwell to be identified as the Author and Illustrator of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The latest electronic version of this book may be obtained from: http://www.brighthelm.org/ Ye Small Print—Cautionary Note and Disclaimer Combat re-enactment in any form carries an element of risk (hey they used to do this for real!) Even making armour can be hazardous, if you drop a hammer on your foot, cut yourself on a sharp piece of metal or do something even more disastrous! It must be pointed out, therefore, that if you partake in silly hobbies such as these you do so at your own risk! The advice and information in this booklet is given in good faith (most having been tried out by the author) however as I have no control over what you do, or how you do it, I can accept no liability for injury suffered by yourself or others while making or using armour. Ye Nice Note Having said all that I’ll just add that I’ve been playing for ages and am still in one piece and having fun. -

PRD 20160804 V2 (002) 4 AUG 2016

LR PRD 20160804_ v2 (002) 4 AUG 2016 1 PERFORMANCE REQUIREMENTS DOCUMENT (PRD) 2 FOR 3 PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE 4 COMMAND CONTROL COMMUNICATIONS – 5 TACTICAL (PEO C3T) 6 HANDHELD, MANPACK, SMALL FORM FIT (HMS) 7 2- CHANNEL LEADER RADIO 8 PROCUREMENT 9 10 11 12 13 14 VERSION 2 15 4 AUG 2016 16 17 PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE 18 COMMAND CONTROL COMMUNICATIONS – 19 TACTICAL (PEO C3T) 20 6010 FRANKFORD AVENUE 21 ABERDEEN PROVING GROUND, MD 21005 22 23 24 25 26 STATEMENT A – APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION IS 27 UNLIMITED. 1 of 45 LR PRD 20160804_ v2 (002) 4 AUG 2016 28 Table of Contents 29 1 Scope/Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 30 1.1 Scope .............................................................................................................................. 5 31 1.2 System Description ......................................................................................................... 5 32 1.3 Terms and Definitions .................................................................................................... 5 33 2 Applicable Documents .............................................................................................................. 7 34 2.1 Specifications .................................................................................................................. 7 35 Military Standards ..................................................................................................................... -

Armour Weapons

M m et . !Photograph by H auser ' Madnd . Armour ofPhilip II. A R M OU R WEA PONS BY W 10 C H A RLE SA FFO ULKE S W ITH A PREFACE BY V S OUN T DILLON V P A I . C , S. CU RATOR O F T H E T OW ER AR M OU R I ES OXFO R D AT TH E CLARENDO N PRESS NR Y FR OWDE M A HE , . P B I S H TO TH E U N IV E R S I TY X D U L ER . OF O FOR N D N D IN B G H N E W Y K LO O , E UR , OR TORONTO A N D M E LB OURN E 651244 5 7 3 . z , PR E FA C E WR ITE R S on Arms and Armour have approached the s ub je c t s tu de nts th e ir from many points of View , but , as all know , works s o size are generally large in , or , what is more essential , in price , th a t for many who do no t have access to large libraries it is o . imp ssible to learn much that is required Then again , the papers of the Proceedings of the various Antiquarian and Archaeological Societies are in all cases very scattered and , in some cases , unattainable , owing to their being out of print . Many writers on the subj ect have confined themselves to documentary evidence , while others have only written about such examples as have been n e . -

Ansteorran Achievment Armorial

Ansteorran Achievment Armorial Name: Loch Soilleir, Barony of Date Registered: 9/30/2006 Mantling 1: Argent Helm: Barred Helm argent, visor or Helm Facing: dexter Mantling 2: Sable: a semy of compass stars arg Crest verte a sea serpent in annulo volant of Motto Inspiration Endeavor Strength Translation Inspiration Endeavor Strength it's tail Corone baronial Dexter Supporter Sea Ram proper Sinister Supporter Otter rampant proper Notes inside of helm is gules, Sea Ram upper portion white ram, lower green fish. Sits on 3 waves Azure and Argent instead of the normal mound Name: Adelicia Tagliaferro Date Registered: 4/22/1988 Mantling 1: counter-ermine Helm: N/A Helm Facing: Mantling 2: argent Crest owl Or Motto Honor is Duty and Duty is Honor Translation Corone baronial wide fillet Dexter Supporter owl Or Sinister Supporter owl Or Notes Lozenge display with cloak; originally registered 4\22\1988 under previous name "Adelicia Alianora of Gilwell" Name: Aeruin ni Hearain O Chonemara Date Registered: 6/28/1988 Mantling 1: sable Helm: N/A Helm Facing: Mantling 2: vert Crest heron displayed argent crested orbed Motto Sola Petit Ardea Translation The Heron stands alone (Latin) and membered Or maintaining in its beak a sprig of pine and a sprig of mistletoe proper Corone Dexter Supporter Sinister Supporter Notes Display with cloak and bow Name: Aethelstan Aethelmearson Date Registered: 4/16/2002 Mantling 1: vert ermined Or Helm: Spangenhelm with brass harps on the Helm Facing: Afronty Mantling 2: Or cheek pieces and brass brow plate Crest phoenix -

Performance Requirements Document

1 PERFORMANCE REQUIREMENTS DOCUMENT (PRD) 2 FOR 3 PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE 4 COMMAND CONTROL COMMUNICATIONS – 5 TACTICAL (PEO C3T) 6 HANDHELD, MANPACK, SMALL FORM FIT (HMS) 7 2- CHANNEL LEADER RADIO 8 PROCUREMENT 9 10 11 12 13 14 18 AUGUST 2017 15 16 PROGRAM EXECUTIVE OFFICE 17 COMMAND CONTROL COMMUNICATIONS – 18 TACTICAL (PEO C3T) 19 6010 FRANKFORD AVENUE 20 ABERDEEN PROVING GROUND, MD 21005 21 22 23 24 25 STATEMENT A – APPROVED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE; DISTRIBUTION IS 26 UNLIMITED. Attachment 0011, LR PRD 18 August 2017 27 Table of Contents 28 Scope/Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 29 Scope .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 30 System Description .............................................................................................................................. 5 31 Terms and Definitions ........................................................................................................................ 5 32 Threshold Requirements (T) .................................................................................................... 6 33 Delayed Threshold Requirements (DT) ............................................................................... 6 34 Objective Requirements (O) ..................................................................................................... 6 -

Military Technology in the 12Th Century

Zurich Model United Nations MILITARY TECHNOLOGY IN THE 12TH CENTURY The following list is a compilation of various sources and is meant as a refer- ence guide. It does not need to be read entirely before the conference. The breakdown of centralized states after the fall of the Roman empire led a number of groups in Europe turning to large-scale pillaging as their primary source of income. Most notably the Vikings and Mongols. As these groups were usually small and needed to move fast, building fortifications was the most efficient way to provide refuge and protection. Leading to virtually all large cities having city walls. The fortifications evolved over the course of the middle ages and with it, the battle techniques and technology used to defend or siege heavy forts and castles. Designers of castles focused a lot on defending entrances and protecting gates with drawbridges, portcullises and barbicans as these were the usual week spots. A detailed ref- erence guide of various technologies and strategies is compiled on the following pages. Dur- ing the third crusade and before the invention of gunpowder the advantages and the balance of power and logistics usually favoured the defender. Another major advancement and change since the Roman empire was the invention of the stirrup around 600 A.D. (although wide use is only mentioned around 900 A.D.). The stirrup enabled armoured knights to ride war horses, creating a nearly unstoppable heavy cavalry for peasant draftees and lightly armoured foot soldiers. With the increased usage of heavy cav- alry, pike infantry became essential to the medieval army.