Drummond Island Resource Management Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CORA Code – Great Lakes Fishing Regulations

CHIPPEWA OTTAWA RESOURCE AUTHORITY COMMERCIAL, SUBSISTENCE, AND RECREATIONAL FISHING REGULATIONS FOR THE 1836 TREATY CEDED WATERS OF LAKES SUPERIOR, HURON, AND MICHIGAN Adopted August 31, 2000 Effective September 7, 2000 Revised March 4, 2019 CHIPPEWA OTTAWA RESOURCE AUTHORITY COMMERCIAL, SUBSISTENCE, AND RECREATIONAL FISHING REGULATIONS FOR THE 1836 TREATY CEDED WATERS OF LAKES SUPERIOR, HURON, AND MICHIGAN CONTENTS PART ONE: GENERAL MATTERS PART FIVE: NON-COMMERCIAL FISHING I. Purpose……………………………………1 XVII. Recreational Fishing……………………….…28 II. Scope and Application……………………1 XVIII. Tribal Charter Boat Operations………………28 III. Definitions……………………………...1-4 XIX. Subsistence Fishing……………………….28-30 PART TWO: ZONES PART SIX: LICENSES AND INFORMATION IV. Commercial Fishing Zones………………4 XX. License and Registration Definitions and Regulations…………………………………...30 V. Tribal Zones………………………........4-8 XXI. License Regulations……………………....31-32 VI. Intertribal Zones………………………8-10 XXII. Harvest Reporting and Sampling………....32-34 VII. Trap Net Zones…………………........10-12 XXIII. Assessment Fishing……………………… 34-35 VIII. Closed or Limited Fishing Zones……12-14 PART THREE: GEAR PART SEVEN: REGULATION AND ENFORCEMENT IX. Gear Restrictions……….…………......14-17 XXIV. Tribal Regulations……………………………35 X. State-Funded Trap Net Conversion Operations……………………………17-18 XXV. Orders of the Director…………………..........35 XXVI. Jurisdiction and Enforcement…………….35-37 PART FOUR: SPECIES XXVII. Criminal Provisions………………………….37 XI. Lake Trout…………………………...18-19 XII. Salmon……………………………….19-21 PART EIGHT: ACCESS XIII. Walleye…………………………….…21-23 XXVIII. Use of Access Sites……………………..37-38 XIV. Yellow Perch………………………...23-26 XV. Other Species………………………...26-27 XVI. Prohibited Species……………………… 27 CHIPPEWA OTTAWA RESOURCE AUTHORITY COMMERCIAL, SUBSISTENCE, AND RECREATIONAL FISHING REGULATIONS FOR THE 1836 TREATY CEDED WATERS OF LAKES SUPERIOR, HURON, AND MICHIGAN PART ONE: GENERAL MATTERS SECTION I. -

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13Th) Edition

Distances Between United States Ports 2019 (13th) Edition T OF EN CO M M T M R E A R P C E E D U N A I C T I E R D E S M T A ATES OF U.S. Department of Commerce Wilbur L. Ross, Jr., Secretary of Commerce National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) RDML Timothy Gallaudet., Ph.D., USN Ret., Assistant Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere and Acting Under Secretary of Commerce for Oceans and Atmosphere National Ocean Service Nicole R. LeBoeuf, Deputy Assistant Administrator for Ocean Services and Coastal Zone Management Cover image courtesy of Megan Greenaway—Great Salt Pond, Block Island, RI III Preface Distances Between United States Ports is published by the Office of Coast Survey, National Ocean Service (NOS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), pursuant to the Act of 6 August 1947 (33 U.S.C. 883a and b), and the Act of 22 October 1968 (44 U.S.C. 1310). Distances Between United States Ports contains distances from a port of the United States to other ports in the United States, and from a port in the Great Lakes in the United States to Canadian ports in the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence River. Distances Between Ports, Publication 151, is published by National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency (NGA) and distributed by NOS. NGA Pub. 151 is international in scope and lists distances from foreign port to foreign port and from foreign port to major U.S. ports. The two publications, Distances Between United States Ports and Distances Between Ports, complement each other. -

Biodiversity of Michigan's Great Lakes Islands

FILE COPY DO NOT REMOVE Biodiversity of Michigan’s Great Lakes Islands Knowledge, Threats and Protection Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist April 5, 1993 Report for: Land and Water Management Division (CZM Contract 14C-309-3) Prepared by: Michigan Natural Features Inventory Stevens T. Mason Building P.O. Box 30028 Lansing, MI 48909 (517) 3734552 1993-10 F A report of the Michigan Department of Natural Resources pursuant to National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Award No. 309-3 BIODWERSITY OF MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS Knowledge, Threats and Protection by Judith D. Soule Conservation Research Biologist Prepared by Michigan Natural Features Inventory Fifth floor, Mason Building P.O. Box 30023 Lansing, Michigan 48909 April 5, 1993 for Michigan Department of Natural Resources Land and Water Management Division Coastal Zone Management Program Contract # 14C-309-3 CL] = CD C] t2 CL] C] CL] CD = C = CZJ C] C] C] C] C] C] .TABLE Of CONThNTS TABLE OF CONTENTS I EXECUTIVE SUMMARY iii INTRODUCTION 1 HISTORY AND PHYSICAL RESOURCES 4 Geology and post-glacial history 4 Size, isolation, and climate 6 Human history 7 BIODWERSITY OF THE ISLANDS 8 Rare animals 8 Waterfowl values 8 Other birds and fish 9 Unique plants 10 Shoreline natural communities 10 Threatened, endangered, and exemplary natural features 10 OVERVIEW OF RESEARCH ON MICHIGAN’S GREAT LAKES ISLANDS 13 Island research values 13 Examples of biological research on islands 13 Moose 13 Wolves 14 Deer 14 Colonial nesting waterbirds 14 Island biogeography studies 15 Predator-prey -

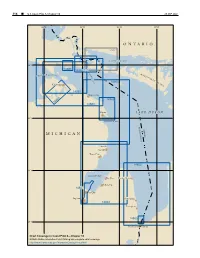

M I C H I G a N O N T a R

314 ¢ U.S. Coast Pilot 6, Chapter 10 26 SEP 2021 85°W 84°W 83°W 82°W ONTARIO 2251 NORTH CHANNEL 46°N D E 14885 T 14882 O U R M S O F M A C K I N A A I T A C P S T R N I A T O S U S L A I N G I S E 14864 L A N Cheboygan D 14881 Rogers City 14869 14865 14880 Alpena L AKE HURON 45°N THUNDER BAY UNITED ST CANADA MICHIGAN A TES Oscoda Au Sable Tawas City 14862 44°N SAGINAW BAY Bay Port Harbor Beach Sebewaing 14867 Bay City Saginaw Port Sanilac 14863 Lexington 14865 43°N Port Huron Sarnia Chart Coverage in Coast Pilot 6—Chapter 10 NOAA’s Online Interactive Chart Catalog has complete chart coverage http://www.charts.noaa.gov/InteractiveCatalog/nrnc.shtml 26 SEP 2021 U.S. Coast Pilot 6, Chapter 10 ¢ 315 Lake Huron (1) Lawrence, Great Lakes, Lake Winnipeg and Eastern Chart Datum, Lake Huron Arctic for complete information.) (2) Depths and vertical clearances under overhead (12) cables and bridges given in this chapter are referred to Fluctuations of water level Low Water Datum, which for Lake Huron is on elevation (13) The normal elevation of the lake surface varies 577.5 feet (176.0 meters) above mean water level at irregularly from year to year. During the course of each Rimouski, QC, on International Great Lakes Datum 1985 year, the surface is subject to a consistent seasonal rise (IGLD 1985). -

Integrated Assessment Cisco (Coregonus Artedi) Restoration in Lake Michigan FACT SHEET: Management/Restoration Efforts in the Great Lakes

Integrated Assessment Cisco (Coregonus artedi) Restoration in Lake Michigan FACT SHEET: Management/Restoration Efforts in the Great Lakes General In the Great Lakes Basin, a number of tools are available to manage Cisco stocks including restoration when populations are depleted. Active tools that have Been used include harvest regulations, habitat protection and enhancement, and population enhancement and re-introduction via stocking. Cisco management in each lake is the purview of individual jurisdictions. Regulation of commercial and recreational fisheries in the Great Lakes is under the authority of eight individual U. S. states, the Canadian province of Ontario (Fig.1), and triBal governments. In the United States Great Lakes, three intertribal organizations regulate treaty-based harvest on ceded lands and water beyond the reservations: the Great Lakes Indian Fish and Wildlife Commission, the Chippewa Ottawa Resource Authority and the 1854 Treaty Authority (CORA 2000, Kappen et al 2012). Four treaties reserve triBal fishing rights including suBsistence fishery in Michigan, Wisconsin and Minnesota. In the Canadian Great Lakes, the Aboriginal Communal Fishing Licences Regulations provides communal fishing licenses as a management tool for Aboriginal fisheries, which are found on all lakes except Lake Erie. This fact sheet summarizes cisco management for each lake excluding harvest regulations for tribal fisheries which are not aligned with one lake (Fig. 2). Figure 1. Great Lakes bordering states (GLIN.net) 1 Integrated Assessment Cisco (Coregonus artedi) Restoration in Lake Michigan FACT SHEET: Management/Restoration Efforts in the Great Lakes Figure 2 .Treaty-ceded waters in the Great Lakes with tribal fishing rights reaffirmed based on 1836, 1842, and 1854 treaties between Native American tribes and the U.S. -

Research Report Michigan Department of Natural Resources Fisheries Division

STATE OF MICHIGAN Michigan DNR DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES Number 2049 October 29, 1998 Lake Herring Spawning Grounds of the St. Marys River with Potential Effects of Early Spring Navigation David G. Fielder FISHERIES DIVISION RESEARCH REPORT MICHIGAN DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES FISHERIES DIVISION Fisheries Research Report 2049 October 29, 1998 LAKE HERRING SPAWNING GROUNDS OF THE ST. MARYS RIVER WITH POTENTIAL EFFECTS OF EARLY SPRING NAVIGATION David G. Fielder The Michigan Department of Natural Resources, (MDNR) provides equal opportunities for employment and for access to Michigan’s natural resources. State and Federal laws prohibit discrimination on the basis of race, color, sex, national origin, religion, disability, age, marital status, height and weight. If you believe that you have been discriminated against in any program, activity or facility, please write the MDNR Equal Opportunity Office, P.O. Box 30028, Lansing, MI 48909, or the Michigan Department of Civil Rights, 1200 6th Avenue, Detroit, MI 48226, or the Office of Human Resources, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Washington D.C. 20204. For more information about this publication or the American Disabilities Act (ADA), contact, Michigan Department of Natural Resources, Fisheries Division, Box 30446, Lansing, MI 48909, or call 517-373-1280. Printed under authority of Michigan Department of Natural Resources Total number of copies printed 200 — Total cost $348.23 — Cost per copy $1.74 Michigan Department of Natural Resources Fisheries Research Report No. 2049, 1998 Lake Herring Spawning Grounds of the St. Marys River with Potential Effects of Early Spring Navigation David G. Fielder Michigan Department of Natural Resources Alpena Great Lakes Fisheries Research Station 160 East Fletcher Alpena, MI 49707-2344 Abstract.–The St. -

STATUS of WALLEYE in the GREAT LAKES: CASE STUDIES PREPARED for the 1989 WORKSHOP Edited by Peter J

STATUS OF WALLEYE IN THE GREAT LAKES: CASE STUDIES PREPARED FOR THE 1989 WORKSHOP edited by Peter J. Colby Ministry of Natural Resources Fisheries Research Section, Walleye Unit 435 S. James Street P.O. Pox 5000 Thunder Day, Ontario, Canada P7C 5G6 Cheryl A. Lewis Ministry of Natural Resources Glenora Fisheries Station R. R. #4 Picton, Ontario, Canada KOK 2T0 Randy L. Eshenroder Great Lakes Fishery Commission 1451 Green Road Ann Arbor, MI 48105-2898 Citation (general): Colby, P. J., C. A. Lewis, and R. L. Eshenroder, [ED.]. 1991. Status of walleye in the Great Lakes: case studies prepared for the 1989 workshop. Great Lakes Fish. Comm. Spec. Pub. 91-l. 222 p. Citation (example for individual paper): Schram, S. T., J. R. Atkinson, and D. L. Pereira. 1991. Lake Superior walleye stocks : status and management, p. l-22. In P. J. Colby, C. A. Lewis, and R. L. Eshenroder [ed.]. Status of walleye in the Great Lakes: case studies prepared for the 1989 workshop. Great Lakes Fish. Comm. Spec. Pub. 91-l. Special Publication No. 91-1 GREAT LAKES FISHERY COMMISSION 1451 Green Road Ann Arbor, MI 48105 January 1991 The case studies in this publication were produced as preparatory material for the Walleye Rehabilitation Workshop held June 5-9, 1990 at the Franz-Theodore Stone Laboratory at Put-in-Ray, Ohio. This workshop was sponsored by the Great Lakes Fishery Commission's Board of Technical Experts. For a number of years, Henry H. Regier had urged the Board to initiate such a study to document recent changes in walleye populations that were particularly evident inwestern Lake Erie. -

Fo-219.08 Waters Open to the Use of Spears and Bows

FO-219.08 WATERS OPEN TO THE USE OF SPEARS AND BOWS By authority conferred on the Department of Natural Resources by section 48703 of 1994 PA 451, MCL 324.48703, it is ordered that effective, November 6, 2008, for a period of five years, the following regulations are established for waters open to the use of spears and bows: The seasons, waters, and species where a hand propelled spear may be used are as specified in the table below and lists which follow (except as otherwise prohibited). In addition, a bow, rubber-propelled spear, spring-propelled spear, or light may be used where noted. SEASON WATERS SPECIES All waters (through the ice) except: Designated Trout December 1 – March 15 Lakes (FO-200) and Streams (FO-210), and specific Northern Pike FO-220 waters. No muskellunge spearing on Muskellunge L. St. Clair, L. Erie, Detroit R., and St. Clair R. January 1 – end of February L. St. Clair (bow may be used) Yellow perch January 1 – end of February (bow and light may be used) Inland non-trout waters Bowfin Carp (through the ice): See FO-220. Bullheads Gar Catfish Drum All year (Note 1) (bow and light may be used) Great Lakes, L. St. Cisco Whitefish Clair, St. Marys R., St. Clair R., and Detroit R. Suckers Smelt All year Great Lakes Burbot April 1 - May 31 South of highway M-46 April 15-May 31 (bow and light may be used) Between highways All non-trout streams Bowfin M-46 and M-72 Trout streams in List A Carp May 1 - 31 Gar North of highway M-72 Suckers (submerged under water with rubber or spring All Year propelled spears only) Waters in List B May 1 - August 15 (bow and light may be used) Bowfin Carp Inland non-trout waters Gar October 15 - December 31 (light may be used) Hubbard L. -

Georgian Bay

Great Lakes Cruising Club Copyright 2009, Great Lakes Cruising Club INDEX Port Pilot and Log Book INCLUDES The Great Lakes Cruising Club, its members, agents, or servants, shall not be liable, and user waives all claims, for damages to persons or property sustained by or arising from the use of this report. ALPHABETICAL INDEX — PAGE 3 GEOGRAPHICAL INDEX — PAGE 17 Page 2 / Index Note: all harbor reports are available to GLCC members on the GLCC website: www.glcclub.com. Members are also encouraged to submit updates directly on the web page. The notation NR indicates that no report has yet been prepared for that harbor. Members are asked to provide information when they NR visit those harbors. A guide to providing data is available in Appendix 2. A harbor number in brackets, such as [S-14], following another report number indicates that there is no individual report for that [ ] harbor but that information on it is contained in the bracketed harbor report. The notation (OOP) indicates that a report is out-of-print, with OOP indefinite plans for republishing. The Great Lakes Cruising Club, its members, agents, and servants shall not be liable, and the user waives all claims for damages to persons or property sustained by or arising from the use of the Port Pilot and Log Book. Index compiled and edited by Ron Dwelle Copyright Great Lakes Cruising Club, 2009 PO Box 611003 Port Huron, Michigan 48061-1003 810-984-4500 [email protected] Page 2 ___________________________________________________________________ Great Lakes Cruising Club — Index -

On the Great Lakes Through 1956

U. S. FEDERAL FISHERY RESEARCH ON THE GREAT LAKES THROUGH 1956 MarineLIBRARYBiological Laboratory DEC 1 1 1957 WOODS HOLE, MASS. SPECIAL SCIENTIFIC REPORT- FISHERIES No. 226 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE . EXPLANATORY NOTE The series embodies results of investigations, usually of restricted scope, intended to aid or direct management or utilization practices and as guides for administrative or legislative action. It is issued in limited quantities for official use of Federal, State or cooperating agencies and in processed form for economy and to avoid delay in publication United States Department of the Interior, Fred A. Seaton, Secretary Fish and Wildlife Service, ArnieJ. Suomela, Commissioner U.S. FEDERAL FISHERY RESEARCH ON THE GREAT LAKES THROUGH 1956 By Ralph Hile Fishery Research Biologist Bureau of Commercial Fisheries Special Scientific Report- -Fisheries No. 226 Washington, D. October 1957 ABSTRACT The present article is a revision and expansion of my earlier paper: 25 years of Federal Fishery Research on the Great Lakes. Spec. Sci. Rep.: Fish. No. 85, 1952. Two circumstances made a revision desirable at this time. First, publications since 1952 have added greatly to the literature based on Federal studies on the Great Lakes. Second, the Great Lakes Fishery Commission, established by treaty with Canada, was organized in Ottowa in April 1956 and held its first annual meeting in Ann Arbor in November 1956. The entry of the Commission on the scene marKs the start of an era of further expansion -

CHIPPEWA County 46.135070N 83.672709W 83.407201W LEGEND

46.135070N 1990 COUNTY BLOCK MAP (RECREATED): CHIPPEWA County 46.135070N 83.672709W 83.407201W LEGEND SYMBOL NAME STYLE INTERNATIONAL AIR Trust Land TJSA / TDSA / ANVSA STATE (or statistically equivalent entity) COUNTY (or statistically equivalent entity) MINOR CIVIL DIV.1 / CCD Place within Subject Entity Incorporated Place / CDP 1 Place outside of Subject Entity Incorporated Place / CDP 1 Potagannissing Bay Corporate Offset Boundary Census Tract / BNA2 3 BLOCK CANADA ABBREVIATION REFERENCE: AIR = American Indian Reservation; Trust Land = Off−Reservation Trust Land; TJSA = Tribal Jurisdiction Statistical Area; TDSA = Tribal Designated Statistical Area; ANVSA = Alaska Native Village Statistical Area; ANRC = Alaska Native Regional Corporation; CCD = Census Civil Division; CDP = Census Designated Place; BNA = Block Numbering Area FEATURES S Maxton Rd FEATURES FEATURES Dawson Lake Pipe/Power Line Ridge/Physical Feature Jeep Trail/Walkway/Ferry Property/Fence Line River / Lake Railroad Nonvisible Boundary Glacier E oP e P t R d P o e P t R 102* d Military Inset Out Area 103 Where international, state, and/or county boundaries coincide, the map shows the boundary symbol for only the highest−ranking of these boundaries. S M a x t o n R d 1 M A ' ° ' following a place name indicates that the place is also a false MCD; a the false MCD name is not shown. d x R t 101 o 2 In 1990, the crews−of−vessels population of ships at sea was allocated to n p census tracts with a '.99' suffix. An anchor symbol appeared on the 1990 m R a d maps locating a crews−of−vessel tract. -

Superior Wildlands a FREE GUIDE to Your Central and Eastern Upper Penin Sula Federal Lands 2013 LAKE SUPERIOR LAKE MICHIGAN LAKE HURON

Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore Seney National Wildlife Refuge Hiawatha National Forest Superior Wildlands A FREE GUIDE To Your Central and Eastern Up per Pen in sula Federal Lands 2013 LAKE SUPERIOR LAKE MICHIGAN LAKE HURON ©Craig Blacklock Today we call them the Great Lakes. First Nation larger basins. Native Americans paddled these waters for people gave them names like Kitchi Gummi for Lake Superi- millennia before Europeans knocked on the door. French or and Michi Gami for Lake Michigan. No matter the name, Canadian and English fur traders moved their trade goods these lakes exert an enormous presence on our lives and over these waters to barter for skins of beaver, mink, fox, the land we live in. At the very least we must be impressed and wolf. Since then, mining, logging, fishing, blast furnace, with their size and grandeur. Superior, for example, is the U.S. Life Saving Service, U.S. Lighthouse Service, and U.S. largest Great Lake by surface area and second largest lake Coast Guard workers have hugged these shorelines. Today, on Earth by volume. Lake Michigan is the second largest we are still drawn to the water’s edge to ice fish, kayak, sail, Great Lake and fifth world-wide. It would take a four foot or just relax on a rocky shore or beach. Countless recre- deep swimming pool the size of the continental U.S. to con- ational hours are spent by millions beside or on the lakes. tain all of Lake Superior’s water! Perhaps one of the most interesting treasures is hid- The sheer size of the lake is impressive.