Punishment for Crime in North Carolina Albert Coates

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Settlers, Africans, and Inter-Personal Violence in Kenya, Ca. 1900-1920S

International Journai of African Historicai studies Vol. 45, No. 1 (2012) 57 Settlers, Africans, and Inter-Personal Violence in Kenya, ca. 1900-1920s By Brett Shadle Virginia Tech ([email protected]) As Fanon noted, violence was inherent in inter-racial relations in settler colonies, and Ngugi reiterated this point specifically in regard to Kenya.' When attempting to write a cultural history of white settlers, Ngugi found nothing of value. He observed only garish paintings in upscale Nairobi bars featuring scenes of colonial life: scrawny Africans pulling whites in rickshaws, a "long bull-necked, bull-faced settler" holding a sjambock (Afrikaans: whip) and his loyal (and well-fed) dog at his side. It was just such a scene, Ngugi refiected, that summed up white settlement: "The rickshaw. The dog. The sjambock. The ubiquitous underfed, wide-eyed, uniformed native slave."2 In the end, as Ngugi put it, "Reactionary violence to instill fear and silence was the very essence of colonial settler culture."3 As is so often the case, Ngugi cut to the heart of the matter: one cannot envision the settler without the sjambock, or in Kenyan parlance, the kiboko (hippopotamus-hide vvhip).'^ Often settlers considered beatings as part and parcel of life in Africa, almost akin to milking the cows or cleaning the kitchen (if, in fact, Europeans ever performed such menial tasks). In the flrst several decades of colonial Kenya, settlers certainly did not hesitate to discuss their use of the lash. In a letter to the East African Standard in 1927, Frank Watkins bragged that, "I thrash my boys if they deserve it and I will let [African defender and settler critic] Archdeacon Owen or anyone else enquire into my methods of handling and working labour."5The Times of East Africa believed, "Probably there is not ' Franz Fanon, Wretched of the Earth (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1963); Ngugi wa Thiong'o, Detained: A Writer's Prison Diary (London: Heinemann, 1981), Chap. -

Report Cover and Inside Pages

Report of North Carolina Crimes to the Criminal Recodification Working Group Prepared by North Carolina Administrative office of the courts January 31, 2019 About the North Carolina Judicial Branch The mission of the North Carolina Judicial Branch is to protect and preserve the rights and liberties of all the people as guaranteed by the Constitutions and laws of the United States and North Carolina by providing a fair, independent and accessible forum for the just, timely and economical resolution of their legal affairs. About the North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts The mission of the North Carolina Administrative Office of the Courts is to provide services to help North Carolina’s unified court system operate more efficiently and effectively, taking into account each courthouse’s diverse needs, caseloads, and available resources. Introduction The North Carolina General Assembly established the Criminal Law Recodification Working Group in 2017. This informal group, co-chaired by Representative Dennis Riddell and Senator Andy Wells, has been tasked with developing strategies to streamline and simply the state’s criminal code. In 2018, the General Assembly enacted S.L. 2018-69 which requires multiple agencies to provide information to the Working Group. Specifically, the legislation requires the Administrative Office of the Courts (AOC) to identify and list all state crimes that meets one or more of the following criteria: (1) The statute is duplicative. (2) The statute is inconsistent with other statutes, rarely charged, fails to state a mens rea, or contains undefined terms. (3) The statute appears to be obsolete. (4) The statute has been held to be unconstitutional by an appellate court. -

DNA Samples/All Felonies. (Public) Sponsors: Senator Pittenger

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA SESSION 2003 S D SENATE DRS15018-LH-30 (1/28) Short Title: DNA Samples/All Felonies. (Public) Sponsors: Senator Pittenger. Referred to: 1 A BILL TO BE ENTITLED 2 AN ACT TO PROVIDE THAT A DNA SAMPLE AND ANALYSIS SHALL BE 3 REQUIRED OF ANY PERSON CONVICTED OF A FELONY. 4 The General Assembly of North Carolina enacts: 5 SECTION 1. G.S. 15A-266.1 reads as rewritten: 6 "§ 15A-266.1. Policy. 7 It is the policy of the State to assist federal, State, and local criminal justice and law 8 enforcement agencies in the identification, detection, or exclusion of individuals who 9 are subjects of the investigation or prosecution of felonies and violent crimes against the 10 person. Identification, detection, and exclusion is facilitated by the analysis of biological 11 evidence that is often left by the perpetrator or is recovered from the crime scene. The 12 analysis of biological evidence can also be used to identify missing persons and victims 13 of mass disasters." 14 SECTION 2. G.S. 15A-266.4 reads as rewritten: 15 "§ 15A-266.4. Blood sample required for DNA analysis upon conviction. 16 (a) On or after 1 July 1994, a person who is convicted of any of the crimes listed 17 in subsection (b) of this section shall have a DNA sample drawn upon intake to a jail or 18 prison. In addition, every person convicted on or after 1 July 1994, of any of these 19 crimes, but who is not sentenced to a term of confinement, shall provide a DNA sample 20 as a condition of the sentence. -

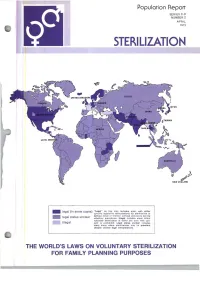

Population Reports. Series C-D, Number 2: Sterilization. the World's

Population Report SERIES C-D NUMBER 2 APRIL 1973 STERI LIZATIO PAN o ~J> NEW ZEALAND legal (in some cases) "l.I!gal" on this map includes areas with either spec llic legislative au thorizations for sterilizallon or legal status unclear without direct or indirect crim inal provisions barrin g voluntary p ro cedu res. Illegal Inclu des areas where voluntary steriliz8tion 01 either sex even with con- illegal sent is prohibited. Legal ...IUI unclear Includes many areas where sterll izations may be prevalent despite unclear legal interpretations. THE WORLD'S LAWS ON VOLUNTARY STERILIZATION FOR FAMILY PLANNING PURPOSES Population Report SERIES C-D NUMBER 2 APRIL 1973 STERILIZATION Department of Medical and Public Affai~, The George Washington Unive~ity Medical Center, 2001 S Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20009 THE WORLD'S LAWS ON VOLUNTARY STERILIZATION FOR FAMILY PLANNING PURPOSES JAN STEPAN J.U.Dr, C.Sc., Reference Librarian, Harvard Law School, and Consultant, Law and Population Programme. and EDMUND H. KELLOGG A.B., J.D., Deputy Director, Law and Population Programme, Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. This monograph is one in a continuing series published under the auspices of the Law and Population Programme, the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy. The Law and Population Programme and its field work are supported in part by the International Planned Parenthood Federation, the United Nations Fund for Population Activities, and the U. S. Agency for International Development, among others. The Programme is under the general direction of an International Advisory Committee on Population and Law, whose members are listed at the end of this monograph. -

Criminal Volume Index Replacement June 2019

Page 1 of 67 N.C.P.I—Criminal Volume Index Replacement June 2019 CRIMINAL VOLUME INDEX (All references are to N.C.P.I.–Criminal instruction numbers) ABANDONMENT. By supporting spouse, 240.05. By parent, 240.07 (felony); 240.06 (misdemeanor). ABDUCTION. See CHILD OR CHILDREN, FALSE IMPRISONMENT, KIDNAPPING. ABSENCE OF DEFENDANT, 101.32 ABSENCE OF MOTIVE, 104.10. ABUSE OF CHILDREN. See CHILD OR CHILDREN, MINORS. ACADEMIC CREDIT, OBTAINING BY0. ACCESSORIES AND PRINCIPALS. Accessory after the fact, 202.40. Accessory before the fact, 202.30. Accessory before the fact, first degree murder, 206.10A. Acting in concert, 202.10. Aiding and abetting, 202.20A. Compounding crime, 202.50. ACCIDENT (Homicide), 206.10 (p. 9); 307.10 (defense to homicide); 307.11 (defense in cases other than homicide). ACCOMPLICE TESTIMONY, 104.25. ACCUSATION OF CRIME. See BLACKMAIL. ACID OR ALKALI—MALICIOUS THROWING, 208.08. ACTING IN CONCERT, 202.10. ACTUAL—CONSTRUCTIVE POSSESSION, 104.41. ADEQUATE SUPPORT OF ILLEGITIMATE CHILD, FAILURE TO PROVIDE, 240.40. ADMINISTRATION OF JUSTICE, OBSTRUCTING, 230.40. ADMISSIONS. By defendant, 104.60. ADULTERATION, MISBRANDING OF FOOD, DRUGS, COSMETICS. Extortion by, 208.96B. With intent to injure, 208.96A. ADULTERY, 226.50. ADVANCES, OBTAINING UNDER PROMISE TO WORK, 219.20. ADVERTISING, FRAUDULENT AND DECEPTIVE, 220.40. Page 2 of 67 N.C.P.I—Criminal Volume Index Replacement June 2019 AFFRAY, SIMPLE, 208.43. AGGRAVATED ASSAULT ON A HANDICAPPED PERSON, 208.50A. AGGRAVATED FELONY DEATH BY VEHICLE, 206.57B. AGGRAVATED FELONY SERIOUS INJURY BY VEHICLE, 206.57D. AGGRAVATING CONDITIONS APPLICABLE TO DRUG CHARGES, 260.45. AGGRAVATING FACTOR INSTRUCTION, 204.25. -

2015 Punishment Chart for North Carolina Crimes and Motor Vehicle Offenses

2015 Punishment Chart for North Carolina Crimes and Motor Vehicle Offenses ROBERT L. FARB The School of Government at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill works to improve the lives of North Carolinians by engaging in practical scholarship that helps public officials and citizens understand and improve state and local government. Established in 1931 as the Institute of Government, the School provides educational, advisory, and research services for state and local governments. The School of Government is also home to a nationally ranked graduate program in public administration and specialized centers focused on information technology and environmental finance. As the largest university-based local government training, advisory, and research organization in the United States, the School of Government offers up to 200 courses, webinars, and specialized conferences for more than 12,000 public officials each year. In addition, faculty members annually publish approximately 50 books, manuals, reports, articles, bulletins, and other print and online content related to state and local government. Each day that the General Assembly is in session, the School produces the Daily Bulletin Online, which reports on the day’s activities for members of the legislature and others who need to follow the course of legislation. The Master of Public Administration Program is offered in two formats. The full-time, two-year residential program serves up to 60 students annually. In 2013 the School launched MPA@UNC, an online format designed for working professionals and others seeking flexibility while advancing their careers in public service. The School’s MPA program consistently ranks among the best public administration graduate programs in the country, particularly in city management. -

General Assembly of North Carolina Extra Session 1994

GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA EXTRA SESSION 1994 H 3 HOUSE BILL 39 Committee Substitute Favorable 2/21/94 Committee Substitute #2 Favorable 3/18/94 Short Title: Omnibus 1994 Anti-Crime Act. (Public) ─────────────────────────────────────── Sponsors: ─────────────────────────────────────── Referred to: ─────────────────────────────────────── February 8, 1994 1 A BILL TO BE ENTITLED 2 AN ACT TO ADJUST THE APPROPRIATIONS MADE FOR THE 1993-94 FISCAL 3 YEAR AND THE 1994-95 FISCAL YEAR TO CREATE THE BUDGET 4 MODIFICATION ACT OF 1994, TO INCREASE THE PUNISHMENT UNDER 5 STRUCTURED SENTENCING FOR FIRST DEGREE RAPE AND FIRST 6 DEGREE SEXUAL OFFENSE, INCLUDING LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE FOR 7 THE AGGRAVATED RANGE OF PRIOR RECORD LEVELS V AND VI, TO 8 REPEAL THE PROVISIONS IN THE STRUCTURED SENTENCING ACT 9 THAT RESTRICTED THE DEFINITION OF HABITUAL FELON AND 10 LOWERED THE PUNISHMENT FOR AN HABITUAL FELON FROM CLASS C 11 TO CLASS D, TO PROHIBIT THE POSSESSION OF FIREARMS AND 12 WEAPONS OF MASS DEATH AND DESTRUCTION BY FELONS, TO 13 PROVIDE THAT AN ENHANCED SENTENCE SHALL BE IMPOSED ON A 14 PERSON CONVICTED OF A CLASS A THROUGH E FELONY IF THE 15 PERSON USED, DISPLAYED, OR THREATENED TO USE OR DISPLAY A 16 FIREARM DURING THE COMMISSION OF THE FELONY, AND TO 17 PROVIDE THAT A FIREARM USED IN THE COMMISSION OF A FELONY 18 SHALL BE CONFISCATED AND DISPOSED OF AS ORDERED BY THE 19 COURT UNLESS IT CAN BE ESTABLISHED THAT THE FIREARM IS 20 OWNED BY SOMEONE OTHER THAN THE CONVICTED DEFENDANT, TO 21 LOWER THE AGE OF JUVENILES WHO MAY BE TRANSFERRED TO 22 SUPERIOR COURT FROM 14 TO 13 YEARS OF AGE AND TO AUTHORIZE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF NORTH CAROLINA 1994 1 THE JUVENILE CODE COMMITTEE TO STUDY MANDATORY TRANSFER 2 OF JUVENILES TO SUPERIOR COURT FOR SERIOUS FELONY OFFENSES, 3 TO PROVIDE THAT UPON A THIRD CONVICTION OF CERTAIN VIOLENT 4 FELONIES AN OFFENDER IS A VIOLENT HABITUAL FELON AND SHALL 5 BE SENTENCED TO LIFE IMPRISONMENT WITHOUT PAROLE, UNLESS 6 THE OFFENDER IS SENTENCED TO DEATH FOR A CAPITAL OFFENSE. -

The Death Penalty in Decline: from Colonial America to the Present John D

University of Baltimore Law ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law All Faculty Scholarship Faculty Scholarship 2014 Foreword: The eD ath Penalty in Decline: From Colonial America to the Present John Bessler University of Baltimore School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.law.ubalt.edu/all_fac Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, Criminal Law Commons, and the Law Enforcement and Corrections Commons Recommended Citation Foreword: The eD ath Penalty in Decline: From Colonial America to the Present, 50 Crim. L. Bull. 245 (2014) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@University of Baltimore School of Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RIMI AL LAW BULLETIN Volume 50, Number 2 FOREWORD THE DEATH PE~ALTY IN DECLINE: FROM COLONIAL AMERICA TO THE PRESENT John D. Bessler Foreword The Death Penalty in Decline: From Colonial America to the Present John D. Bessler" In colonial America, corporal punishments-both lethal and non lethal-were a gritty reality of life. The Massachusetts "Body of Uber ties," adopted in 1641, contained twelve capital offenses and authorized the imposition of up to forty lashes. Everything from murder and rebellion, to adultery and bestiality, to blasphemy and witchcraft were punishable by death, with eleven of the twelve offenses-as -

Felony Offense List

FELONY CLASSIFICATION UNDER THE STRUCTURED SENTENCING ACT Offenses committed on or after December 1, 2020 FELONY GENERAL STATUTES OFFENSE CLASS SECTION A 14-17(a) Murder in the 1st degree. (Added a rebuttable presumption for murders involving domestic partners – Effective 12/1/17) A 14-17(c) Murder in the 1st degree (child born alive but dies as a result of injuries prior to birth). (Effective 12/1/13) A 14-23.2(a)(1) and (2) Murder of an unborn child. (Effective 12/1/11) A 14-288.22(a) Unlawful use of a nuclear, biological, or chemical weapon of mass destruction; punishment (injures another). (Effective 11/28/01) B1 14-17(b) Murder in the 2nd degree (except as provided in (b)(1) and (2)). (Was Class B2 – Effective 12/1/12) B1 14-17(c) Murder in the 2nd degree (except as provided in (b)(1) and (2)) (child born alive but dies as a result of injuries prior to birth). (Effective 12/1/13) B1 14-27.21 1st degree forcible rape. (Was G.S. 14-27.2(a)(2) – Effective 12/1/15) (Added the threatened use of the dangerous weapon – Effective 12/1/17) B1 14-27.23 Statutory rape of a child by an adult. (Was G.S. 14-27.2A (Effective 12/1/08) – Effective 12/1/15) B1 14-27.24 1st degree statutory rape. (Was G.S. 14-27.2(a)(1) – Effective 12/1/15) B1 14-27.25(a) Statutory rape of person who is 15 years of age or younger (defendant is at least at least 12 years old and at least six years older than victim). -

Compound News – AVN 2005 Fem Dom Video Production Studio and Play Space (Pittsburgh PA USA)

Compound News – AVN 2005 Fem Dom Video Production Studio and Play Space (Pittsburgh PA USA) Visit the Compound! Current theme rooms include a cross dressing parlor, gothic dungeon, corporal detention center, and jail cell area. All rooms are thematically decorated and mirrored floor to ceiling. Sessions range from 1 hour to several days. Call 412 362 0801 to arrange a session. Boss DVD.Com (MIB Productions) is here right now at booth 446 in the B2B area. You can’t miss me. I’m the small woman with the big energy! I won't be doing any domination sessions while in Las Vegas, but get a trade badge and stop by and say hi, and I will autograph a DVD for you! A whirlwind: Shortly after returning to the US from Venus Fair in October, I headed off to Washington DC on November 4th to attend the Black Rose, and Boss DVDs were in the market place there. November 11th - 14th I flew to DomCon Atlanta where my company BossDVD.Com was the guest of honor (and will be once again at DomCon LA April 28th – May 1st) In May - always to find me at the Europerv in Amsterdam! If you own a shop in the red light district, expect a surprise visit from me. I will be a guest Mistress at Club Doma the week of the Europerv. My 8th trip to OWK is June 1st through 6th. August 18th - 21st I will be at Fetish Con (Tampa Florida). Sessions will be available in Orlando Florida (Studio location TBA) October 7th - 9th finds me at Skin 2 Expo and Rubber Ball. -

Unusual Punishments” in Anglo- American Law: the Ed Ath Penalty As Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual John D

Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy Volume 13 | Issue 4 Article 2 Spring 2018 The onceptC of “Unusual Punishments” in Anglo- American Law: The eD ath Penalty as Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual John D. Bessler Recommended Citation John D. Bessler, The Concept of “Unusual Punishments” in Anglo-American Law: The Death Penalty as Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual, 13 Nw. J. L. & Soc. Pol'y. 307 (2018). https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/njlsp/vol13/iss4/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Northwestern Journal of Law & Social Policy by an authorized editor of Northwestern Pritzker School of Law Scholarly Commons. Copyright 2018 by Northwestern University Pritzker School of Law `Vol. 13, Issue 4 (2018) Northwestern Journal of Law and Social Policy The Concept of “Unusual Punishments” in Anglo-American Law: The Death Penalty as Arbitrary, Discriminatory, and Cruel and Unusual John D. Bessler* ABSTRACT The Eighth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, like the English Bill of Rights before it, safeguards against the infliction of “cruel and unusual punishments.” To better understand the meaning of that provision, this Article explores the concept of “unusual punishments” and its opposite, “usual punishments.” In particular, this Article traces the use of the “usual” and “unusual” punishments terminology in Anglo-American sources to shed new light on the Eighth Amendment’s Cruel and Unusual Punishments Clause. The Article surveys historical references to “usual” and “unusual” punishments in early English and American texts, then analyzes the development of American constitutional law as it relates to the dividing line between “usual” and “unusual” punishments. -

Crime and Punishment in the Royal Navy: Discipline on the Leeward Islands Station, 1784-1812 (England)

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1987 Crime and Punishment in the Royal Navy: Discipline on the Leeward Islands Station, 1784-1812 (England). John D. Byrn Jr Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Byrn, John D. Jr, "Crime and Punishment in the Royal Navy: Discipline on the Leeward Islands Station, 1784-1812 (England)." (1987). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 4345. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/4345 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this manuscript, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. For example: • Manuscript pages may have indistinct print. In such cases, the best available copy has been filmed. • Manuscripts may not always be complete. In such cases, a note will indicate that it is not possible to obtain missing pages. • Copyrighted material may have been removed from the manuscript. In such cases, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, and charts) are photographed by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is also filmed as one exposure and is available, for an additional charge, as a standard 35mm slide or as a 17”x 23” black and white photographic print.