IGNOU Modern World History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Annotated List of Italian Renaissance Humanists, Their Writings About Jews, and Involvement in Hebrew Studies, Ca

An annotated list of Italian Renaissance humanists, their writings about Jews, and involvement in Hebrew studies, ca. 1440-ca.1540 This list, arranged in chronological order by author’s date of birth, where known, is a preliminary guide to Italian humanists’ Latin and vernacular prose and poetic accounts of Jews and Judaic culture and history from about 1440 to 1540. In each case, I have sought to provide the author’s name and birth and death dates, a brief biography highlighting details which especially pertain to his interest in Jews, a summary of discussions about Jews, a list of relevant works and dates of composition, locations of manuscripts, and a list of secondary sources or studies of the author and his context arranged alphabetically by author’s name. Manuscripts are listed in alphabetical order by city of current location; imprints, as far as possible, by ascending date. Abbreviations: DBI Dizionario biografico degli Italiani (Rome: Istituto della enciclopedia italiana, 1960-present) Kristeller, Iter Paul Oskar Kristeller, Iter Italicum: A Finding List of Uncatalogued or Incompletely Catalogued Humanistic Manuscripts of the Renaissance in Italian and Other Libraries; Accedunt alia itinera, 6 vols (London: Warburg Institute; Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1963-1991) Simon Atumano (d. c. 1380) Born in Constantinople and became a Basilian monk in St John of Studion there. Bishop of Gerace in Calabria from 1348 until 1366, and Latin archbishop of Thebes until 1380. During his time in Thebes, which was the capital of the Catalan duchy of Athens, he studied Hebrew and in the mid- to late-1370s he began work on a polyglot Latin-Greek-Hebrew Bible dedicated to Pope Urban VI. -

Spring 2008 Issue

www.diplomacyworld.net Variety Melange Variants: The Spice of Life Notes From the Editor Welcome back to another issue of Diplomacy World. that continues in the coming issues as well! This is now my fifth issue since returning as Lead Editor, and in some ways it was the hardest issue to do. I This issue you’ll also find the results of the latest believe this was simply a case of all the additional time Diplomacy World Writing Contest. While I would have and effort that went into doing Issue #100. It wasn’t until liked to get more entries than I did, at least we received #100 was finished and uploaded to the web site that I enough to actually award the prizes this time! realized how many extra hours I’d been spending each Congratulations to our winners, and keep your eyes week trying to assemble all that material. Sitting back open for future writing contests, or contests of other the next day, I was a bit worried about whether I had run types. If you have suggestions, please let me know. the well (or my personal gas tank) dry. Which leads me into the usual quarterly mantra: this Fortunately, that wasn’t the case. First of all, we had a particular issue, and Diplomacy World as a whole, is few wonderful pieces of material set aside for this issue, only as good as the articles you hobby members submit. starting with Stephen Agar’s variant symphony and I can’t write the whole thing myself, not even with the David McCrumb’s designer notes on 1499: The Italian assistance of the DW Staff…we need your ideas, your Wars. -

Directory Nick Version.Xlsx

Directory of Board Game Library - d20 Board Game Cafe Alpabetical Key to expansions: ⇲❑ = In base box, +❑ = Base required, ❑! = Standalone, +❑? = Base required and ask a member of staff for this expansion. Game Category Expansion Shelf Players Playtime Age+ Year Weight 504 Strategy 5C 2 - 4 30 - 120 10+ 2015 3.45 ...And Then We Held Hands 2 Player 20C 2 30 - 45 10+ 2015 1.75 20th Century Strategy 6C 3 - 5 120 12+ 2010 2.96 221b Baker Street Classic 32A 2 - 6 90 12+ 1975 1.82 3 Commandments, The Light Strategy 29E 3 - 7 45 12+ 2018 1.64 3 Wishes Card & Dice 25A 3 - 5 3 - 5 8+ 2016 1.06 5 Minute Dungeon: Curses! Foiled Co-op ⇲❑ 7D 2 - 6 5 - 30 6+ 2018 1.30 Again! 6 Nimmt Card & Dice 25A 2 - 10 45 8+ 1994 1.22 7 Wonders Light Strategy 27C 2 - 7 30 10+ 2010 2.34 7 Wonders Duel 2 Player 20A 2 30 10+ 2015 2.22 7 Wonders Duel: Pantheon 2 Player +❑ 20A 2 30 - 45 10+ 2016 2.25 7 Wonders: Armada Light Strategy +❑ 26C 3 - 7 40 10+ 2018 2.78 A La Carte Party 5F 2 - 4 30 6+ 1989 1.31 Above and Below Strategy 6A 2 - 4 90 10+ 2015 2.53 Absolute Balderdash Trivia 33B 2 - 6 45 1993 1.47 Adrenaline Adventure/Heavy 10D 3 - 5 30 - 60 10+ 2016 2.30 Age Of Empires 3 Adventure/Heavy 9D 2 - 5 90 - 120 12+ 2007 3.13 Age Of Renaissance Adventure/Heavy 10D 3 - 6 120 - 300 14+ 1996 3.86 Agricola Strategy 5E 1 - 5 30 - 150 12+ 2007 3.64 Agricola Family Edition Family and Kids 22A 1 - 5 30 - 150 12+ 2007 3.64 Airships Strategy 5B 2 - 4 45 - 60 8+ 2007 1.86 Akrotiri 2 Player 20F 2 45 12+ 2014 2.65 Alchemists Strategy 6C 2 - 4 120 12+ 2014 3.88 Alchemists: The King's -

Beyond the Bosphorus: the Holy Land in English Reformation Literature, 1516-1596

BEYOND THE BOSPHORUS: THE HOLY LAND IN ENGLISH REFORMATION LITERATURE, 1516-1596 Jerrod Nathan Rosenbaum A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English and Comparative Literature. Chapel Hill 2019 Approved by: Jessica Wolfe Patrick O’Neill Mary Floyd-Wilson Reid Barbour Megan Matchinske ©2019 Jerrod Nathan Rosenbaum ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Jerrod Rosenbaum: Beyond the Bosphorus: The Holy Land in English Reformation Literature, 1516-1596 (Under the direction of Jessica Wolfe) This dissertation examines the concept of the Holy Land, for purposes of Reformation polemics and apologetics, in sixteenth-century English Literature. The dissertation focuses on two central texts that are indicative of two distinct historical moments of the Protestant Reformation in England. Thomas More's Utopia was first published in Latin at Louvain in 1516, roughly one year before the publication of Martin Luther's Ninety-Five Theses signaled the commencement of the Reformation on the Continent and roughly a decade before the Henrician Reformation in England. As a humanist text, Utopia contains themes pertinent to internal Church reform, while simultaneously warning polemicists and ecclesiastics to leave off their paltry squabbles over non-essential religious matters, lest the unity of the Church catholic be imperiled. More's engagement with the Holy Land is influenced by contemporary researches into the languages of that region, most notably the search for the original and perfect language spoken before the episode at Babel. As the confusion of tongues at Babel functions etiologically to account for the origin of all ideological conflict, it was thought that the rediscovery of the prima lingua might resolve all conflict. -

THE MYTH of 'TERRIBLE TURK' and 'LUSTFUL TURK' Nevs

THE WESTERN IMAGE OF TURKS FROM THE MIDDLE AGES TO THE 21ST CENTURY: THE MYTH OF ‘TERRIBLE TURK’ AND ‘LUSTFUL TURK’ Nevsal Olcen Tiryakioglu A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of Nottingham Trent University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 Copyright Statement This work is the intellectual property of the author. You may copy up to 5% of this work for private study, or personal, non-commercial research. Any re-use of the information contained within this document should be fully referenced, quoting the author, title, university, degree level and pagination. Queries or requests for any other use, or if a more substantial copy is required, should be directed in the owner(s) of the Intellectual Property Rights. i Abstract The Western image of Turks is identified with two distinctive stereotypes: ‘Terrible Turk’ and ‘Lustful Turk.’ These stereotypical images are deeply rooted in the history of the Ottoman Empire and its encounters with Christian Europe. Because of their fear of being dominated by Islam, European Christians defined the Turks as the wicked ‘Other’ against their perfect ‘Self.’ Since the beginning of Crusades, the Western image of Turks is associated with cruelty, barbarity, murderousness, immorality, and sexual perversion. These characteristics still appear in cinematic representations of Turks. In Western films such as Lawrence of Arabia and Midnight Express, the portrayals of Turks echo the stereotypes of ‘terrible Turk’ and ‘lustful Turk.’ This thesis argues that these stereotypes have transformed into a myth and continued to exist uniformly in Western contemporary cinema. The thesis attempts to ascertain the uniformity and consistency of the cinematic image of Turks and determine the associations between this image and the myths of ‘terrible Turk’ and ‘lustful Turk.’ To achieve this goal, this thesis examines the trajectory of the Turkish image in Western discourse between the 11th and 21st centuries. -

The Role of Translation and Interpretation in the Diplomatic Communication Tamas Baranyai

The role of translation and interpretation in the diplomatic communication Tamas Baranyai Abstract: Present short study is dealing with the languages used for diplomatic purposes throughout the history and at present, and concentrates on the different ways for solving the question of language-related understanding between the actors of diplomacy. Since one of the most commonly used methods is the employment of translators and interpreters, this writing is mainly dedicated to the issues concerning translation and interpretation in diplomatic context. Keywords: diplomatic language, translation, interpretation, heteronymous translator, autonomous translator, linguistic and cultural awareness Introduction Diplomacy whose presence in the history of mankind from the very beginning of civilization has been proved by the archeologists is a formal way of communication between the states. Since in most of the cases the various states use different language or even languages in their internal exchanges, the interstate communication usually meets the challenge of having a common language in order to avoid misunderstandings. This common language used for diplomatic purposes is sometimes called ’diplomatic language’. Although most of the diplomatic lexicons and dictionaries mention and explain the notion of diplomatic language, legally, there has never existed such a language. We should accept the explanation of Pitti-Ferrand according to which a diplomatic language is practically the language used by the parties concerned during the actual international -

The Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting

CHICAGO 30 March–1 April 2017 RSA 2017 Annual Meeting, Chicago, 30 March–1 April Photograph © 2017 The Art Institute of Chicago. Institute The Art © 2017 Photograph of Chicago. Institute The Art © 2017 Photograph The Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting The Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting Program Chicago 30 March–1 April 2017 Front and back covers: Jacob Halder and Workshop, English, Greenwich, active 1576–1608. Portions of a Field Armor, ca. 1590. Steel, etched and gilded, iron, brass, and leather. George F. Harding Collection, 1982.2241a-h. Art Institute of Chicago. Contents RSA Executive Board .......................................................................5 RSA Staff ........................................................................................6 RSA Donors in 2016 .......................................................................7 RSA Life Members ...........................................................................8 RSA Patron Members....................................................................... 9 Sponsors ........................................................................................ 10 Program Committee .......................................................................10 Discipline Representatives, 2015–17 ...............................................10 Participating Associate Organizations ............................................. 11 Registration and Book Exhibition ...................................................14 Policy on Recording and Live -

The Boardgamer Magazine

Volume 6, Issue 1 January 2001 The BOARDGAMER Sample file Dedicated To The Competitive Play of Avalon Hill / Victory Games and the Board & Card Games of the World Boardgame Championships Featuring: Successors, Blackbeard, War At Sea, Solitaire Games, Chess Clocks In VITP, World Boardgaming Championships, Buckeye Game Fest and AREA Ratings 2 The Boardgamer Volume 6, Issue 1 January 2001 Current Specific Game AREA Ratings To have a game AREA rated, report the game result to: Glenn Petroski; 6829 23rd Avenue; Kenosha, WI 53143-1233; [email protected] Atlantic Storm Victory In The Pacific Age Of Renaissance 135 Active Players Sep. 15, 2000 157 Active Players Sep. 30, 2000 247 Active Players Aug. 1, 2000 1. Robert Hamel 5509 1. Michael Kaye 6745 1. Ewan McNay 5710 2. Robert Eastman 5295 2. John Pack 6469 2. Harald Henning 5543 3. Ben Knight 5241 3. Alan Applebaum 6330 3. William Crenshaw 5483 4. Brian Hedrick 5217 4. Daniel Henry 6320 4. Nicholas Anner 5440 5. H Scott Buckwalter 5177 5. David Targonski 6315 5. Thomas Taaffe 5386 6. Roy Gibson 5169 6. Casey Adams 6168 6. George Sauer III 5360 7. E Henry Richardson III 5161 7. Andy Gardner 6102 7. Marvin Birnbaum 5351 8. Joshua Gifford 5157 8. Thomas Gregorio 6097 8. James Pei 5340 9. Martin Sample 5140 9. Ray Freeman 5952 9. Mark Giddings 5326 10. Joel Tamburo 5135 10. Alfred Wong 5882 10. James Jordan 5322 11. Aaron Fuegi 5100 11. Joseph Dragan 5866 11. Robert Kircher 5299 12. Ike Porter 5100 12. Bradley Solberg 5774 12. -

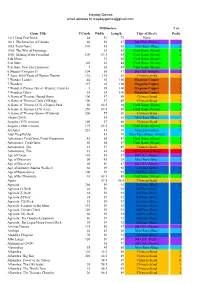

Mayday Games Email Updates to [email protected] # Of

Mayday Games email updates to [email protected] Millimeters # of Game Title # Cards Width Length Type of Sleeve Packs 1313 Dead End Drive 48 53 73 None 1812: The Invasion of Canada 60 56 87 Std USA (Purple) 1 1853 Train Game 110 45 68 Mini Euro (Blue) 2 1955: The War of Espionage 63 88 Card Game (Green) 0 1960: Making of the President 109 63.5 88 Card Game (Green) 2 2 de Mayo 63 88 Card Game (Green) 51st State 126 63 88 Card Game (Green) 2 51st State New Era Expansion 7 63 88 Card Game (Green) 1 6 Nimmt (Category 5) 104 56 87 Std USA (Purple) 2 7 Ages: 6000 Years of Human History 110 110 89 Chimera Sized 2 7 Wonder Leaders 42 65 100 Magnum Copper 1 7 Wonders 157 65 100 Magnum Copper 2 7 Wonders Promos (Stevie Wonder, Catan Island & Mannekin3 Pis) 65 100 Magnum Copper 1 7 Wonders Cities 38 65 100 Magnum Copper 1 A Game of Thrones -Board Game 100 57 89 Chimera Sized 1 A Game of Thrones Clash Of Kings 100 57 89 Chimera Sized 1 A Game of Thrones LCG -Chapter Pack 50 63.5 88 Card Game (Green) 1 A Game of Thrones LCG -Core 250 63.5 88 Card Game (Green) 3 A Game of Thrones Storm Of Swords 200 57 89 Chimera Sized 2 Abetto (2010) 45 68 Mini Euro (Blue) Acquire (1976 version) 180 57 88 Chimera Sized 2 Acquire (2008 version) 175 63.5 88 Card Game (Green) 2 Ad Astra 216 45 68 Mini Euro (Blue) 3 Adel Verpflichtet 45 70 Mini Euro (Blue) -Almost Adventurer Card Game Portal Expansion 45 64 89 Card Game (Green) 1 Adventurer: Card Game 80 64 89 Card Game (Green) 1 Adventurers, The 12 57 89 Chimera Sized 1 Adventurers, The 83 42 64 Mini Chimera (Red) -

Bodies of Knowledge: the Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2015 Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Geoffrey Shamos University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Shamos, Geoffrey, "Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600" (2015). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 1128. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1128 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bodies of Knowledge: The Presentation of Personified Figures in Engraved Allegorical Series Produced in the Netherlands, 1548-1600 Abstract During the second half of the sixteenth century, engraved series of allegorical subjects featuring personified figures flourished for several decades in the Low Countries before falling into disfavor. Designed by the Netherlandsâ?? leading artists and cut by professional engravers, such series were collected primarily by the urban intelligentsia, who appreciated the use of personification for the representation of immaterial concepts and for the transmission of knowledge, both in prints and in public spectacles. The pairing of embodied forms and serial format was particularly well suited to the portrayal of abstract themes with multiple components, such as the Four Elements, Four Seasons, Seven Planets, Five Senses, or Seven Virtues and Seven Vices. While many of the themes had existed prior to their adoption in Netherlandish graphics, their pictorial rendering had rarely been so pervasive or systematic. -

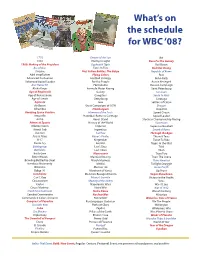

What's on the Schedule For

What’s on the schedule for WBC ‘08? 1776 Empire of the Sun Ra! 1830 Enemy In Sight Race For the Galaxy 1960: Making of the President Euphrat & Tigris Rail Baron Ace of Aces Facts In Five Red Star Rising Acquire Fast Action Battles: The Bulge Republic of Rome Adel Verpflichtet Flying Colors Risk Advanced Civilization Football Strategy Robo Rally Advanced Squad Leader For the People Russia Besieged ASL Starter Kit Formula De Russian Campaign Afrika Korps Formula Motor Racing Saint Petersburg Age of Empires III Galaxy San Juan Age of Renaissance Gangsters Santa Fe Rails Age of Steam Gettysburg Saratoga Agricola Goa Settlers of Catan Air Baron Great Campaigns of ACW Shogun Alhambra Hamburgum Slapshot Amazing Space Venture Hammer of the Scots Speed Circuit Amun-Re Hannibal: Rome vs Carthage Squad Leader Anzio Here I Stand Stockcar Championship Racing Athens & Sparta History of the World Successors Atlantic Storm Imperial Superstar Baseball Attack Sub Ingenious Sword of Rome Auction Ivanhoe Through the Ages Axis & Allies Kaiser's Pirates Thurn & Taxis B-17 Kingmaker Ticket To Ride Battle Cry Kremlin Tigers In the Mist Battlegroup Liar's Dice Tikal Battleline Lost Cities Titan BattleLore Manoeuver Titan Two Bitter Woods Manifest Destiny Titan: The Arena Brawling Battleship Steel March Madness Trans America Breakout Normandy Medici Twilight Struggle Britannia Memoir '44 Union Pacific Bulge '81 Merchant of Venus Up Front Candidate Monsters Ravage America Vegas Showdown Can't Stop Monty's Gamble Victory in the Pacific Carcassonne Mystery of the -

Name, a Novel

NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubu editions 2004 Name, A Novel Toadex Hobogrammathon Cover Ilustration: “Psycles”, Excerpts from The Bikeriders, Danny Lyon' book about the Chicago Outlaws motorcycle club. Printed in Aspen 4: The McLuhan Issue. Thefull text can be accessed in UbuWeb’s Aspen archive: ubu.com/aspen. /ubueditions ubu.com Series Editor: Brian Kim Stefans ©2004 /ubueditions NAME, A NOVEL toadex hobogrammathon /ubueditions 2004 name, a novel toadex hobogrammathon ade Foreskin stepped off the plank. The smell of turbid waters struck him, as though fro afar, and he thought of Spain, medallions, and cork. How long had it been, sussing reader, since J he had been in Spain with all those corkoid Spanish medallions, granted him by Generalissimo Hieronimo Susstro? Thirty, thirty-three years? Or maybe eighty-seven? Anyhow, as he slipped a whip clap down, he thought he might greet REVERSE BLOOD NUT 1, if only he could clear a wasp. And the plank was homely. After greeting a flock of fried antlers at the shevroad tuesday plied canticle massacre with a flash of blessed venom, he had been inter- viewed, but briefly, by the skinny wench of a woman. But now he was in Rio, fresh of a plank and trying to catch some asscheeks before heading on to Remorse. I first came in the twilight of the Soviet. Swigging some muck, and lampreys, like a bad dram in a Soviet plezhvadya dish, licking an anagram off my hands so the ——— woundn’t foust a stiff trinket up me. So that the Soviets would find out.