Correspondence Jeffrey S. Lantis Tom Sauer James J. Wirtz Keir A. Lieber

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Present Status of the River Rhine with Special Emphasis on Fisheries Development

121 THE PRESENT STATUS OF THE RIVER RHINE WITH SPECIAL EMPHASIS ON FISHERIES DEVELOPMENT T. Brenner 1 A.D. Buijse2 M. Lauff3 J.F. Luquet4 E. Staub5 1 Ministry of Environment and Forestry Rheinland-Pfalz, P.O. Box 3160, D-55021 Mainz, Germany 2 Institute for Inland Water Management and Waste Water Treatment RIZA, P.O. Box 17, NL 8200 AA Lelystad, The Netherlands 3 Administrations des Eaux et Forets, Boite Postale 2513, L 1025 Luxembourg 4 Conseil Supérieur de la Peche, 23, Rue des Garennes, F 57155 Marly, France 5 Swiss Agency for the Environment, Forests and Landscape, CH 3003 Bern, Switzerland ABSTRACT The Rhine basin (1 320 km, 225 000 km2) is shared by nine countries (Switzerland, Italy, Liechtenstein, Austria, Germany, France, Luxemburg, Belgium and the Netherlands) with a population of about 54 million people and provides drinking water to 20 million of them. The Rhine is navigable from the North Sea up to Basel in Switzerland Key words: Rhine, restoration, aquatic biodiversity, fish and is one of the most important international migration waterways in the world. 122 The present status of the river Rhine Floodplains were reclaimed as early as the and groundwater protection. Possibilities for the Middle Ages and in the eighteenth and nineteenth cen- restoration of the River Rhine are limited by the multi- tury the channel of the Rhine had been subjected to purpose use of the river for shipping, hydropower, drastic changes to improve navigation as well as the drinking water and agriculture. Further recovery is discharge of water, ice and sediment. From 1945 until hampered by the numerous hydropower stations that the early 1970s water pollution due to domestic and interfere with downstream fish migration, the poor industrial wastewater increased dramatically. -

Wolfgang Wilhelm Sauer Papers, 1913-1989

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf5v19n7wn No online items Preliminary Inventory to the Wolfgang Wilhelm Sauer Papers, 1913-1989 Processed by The Hoover Institution staff; machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi zhou Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2000 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Preliminary Inventory to the 90068 1 Wolfgang Wilhelm Sauer Papers, 1913-1989 Preliminary Inventory to the Wolfgang Wilhelm Sauer Papers, 1913-1989 Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Contact Information Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] Processed by: The Hoover Institution staff Encoded by: Xiuzhi zhou © 2000 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Wolfgang Wilhelm Sauer Papers, Date (inclusive): 1913-1989 Collection number: 90068 Creator: Sauer, Wolfgang Wilhelm, 1920-1989 Collection Size: 68 manuscript boxes27.2 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: Writings, correspondence, notes, curricular material, and printed matter, relating to the history and culture of Germany, German intellectual history, twentieth century German political history, the revolution of November 1918 in Germany, the relationship between President Friedrich Ebert and General Wilhelm Groener, the rise and nature of national socialism in Germany, and militarism as a factor in German history. Includes some papers of Wilhelm Sauer, uncle of W. W. Sauer, relating to jurisprudence and philosophy. Language: German and English. Access Collection open for research. The Hoover Institution Archives only allows access to copies of audiovisual items. -

202.1017 Fld Riwa River Without

VISION FOR THE FUTURE THE QUALITY OF DRINKING WATER IN EUROPE MORE INFORMATION: How far are we? REQUIRES PREVENTIVE PROTECTION OF THE WATER Cooperation is the key word in the activities RESOURCES: of the Association of River Waterworks The Rhine (RIWA) and the International Association The most important of Waterworks in the Rhine Catchment aim of water pollution (IAWR). control is to enable the Cooperation is necessary to achieve waterworks in the structural, lasting solutions. Rhine river basin to Cooperation forges links between produce quality people and cultures. drinking water at any river time. Strong together without And that is one of the primary merits of this association of waterworks. Respect for the insights and efforts of the RIWA Associations of River other parties in this association is growing Waterworks borders because of the cooperation. This is a good basis for successful The high standards for IAWR International Association activities in coming years. the drinking water of Waterworks in the Rhine quality in Europe catchment area Some common activities of the associations ask for preventive of waterworks: protection of the water • a homgeneous international monitoring resources. Phone: +31 (0) 30 600 90 30 network in the Rhine basin, from the Alps Fax: +31 (0) 30 600 90 39 to the North Sea, • scientific studies on substance and parasites Priority must be given E-mail: [email protected] which are relevant for to protecting water [email protected] drinking water production, resources against publication of monitoring pollutants that can The prevention of Internet: www.riwa.org • results and scientific studie get into the drinking water pollution www.iawr.org in annual reports and other water supply. -

Strategien Zur Wiedereinbürgerung Des Atlantischen Lachses

Restocking – Current and future practices Experience in Germany, success and failure Presentation by: Dr. Jörg Schneider, BFS Frankfurt, Germany Contents • The donor strains • Survival rates, growth and densities as indicators • Natural reproduction as evidence for success - suitability of habitat - ability of the source • Return rate as evidence for success • Genetics and quality of stocking material as evidence for success • Known and unknown factors responsible for failure - barriers - mortality during downstream migration - poaching - ship propellers - mortality at sea • Trends and conclusion Criteria for the selection of a donor-strain • Geographic (and genetic) distance to the donor stream • Spawning time of the donor stock • Length of donor river • Timing of return of the donor stock yesterdays environment dictates • Availability of the source tomorrows adaptations (G. de LEANIZ) • Health status and restrictions In 2003/2004 the strategy of introducing mixed stocks in single tributaries was abandoned in favour of using the swedish Ätran strain (Middle Rhine) and french Allier (Upper Rhine) only. Transplanted strains keep their inherited spawning time in the new environment for many generations - spawning time is stock specific. The timing of reproduction ensures optimal timing of hatching and initial feeding for the offspring (Heggberget 1988) and is of selective importance Spawning time of non-native stocks in river Gudenau (Denmark) (G. Holdensgaard, DCV, unpublished data) and spawning time of the extirpated Sieg salmon (hist. records) A common garden experiment - spawning period (lines) and peak-spawning (boxes) of five introduced (= allochthonous) stocks returning to river Gudenau (Denmark) (n= 443) => the Ätran strain demonstrates the closest consistency with the ancient Sieg strain (Middle Rhine). -

Europe's Evolving Deterrence Discourse

EUROPE’S EVOLVING DETERRENCE DISCOURSE EDITED BY AMELIA MORGAN AND ANNA PÉCZELI Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory February 2021 EUROPE’S EVOLVING DETERRENCE DISCOURSE EDITED BY AMELIA MORGAN AND ANNA PÉCZELI Center for Global Security Research Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory King's College London Science Applications International Corporation February 2021 EUROPE’S EVOLVING DETERRENCE DISCOURSE | 1 This work was performed under the auspices of the U.S. Department of Energy by Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in part under Contract W-7405-Eng-48 and in part under Contract DE-AC52-07NA27344. The views and opinions of the author expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States government or Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLC. ISBN-978-1-952565-09-0 LCCN-2020922986 LLNL-TR-815694 TPG-60099 2 | AMELIA MORGAN AND ANNA PÉCZELI Contents About the Contributors 2 Preface Brad Roberts 7 Introduction Amelia Morgan and Heather Williams 8 The (Incomplete) Return of Deterrence Michael Rühle 13 The German Debate: The Bundestag and Nuclear Deterrence Pia Fuhrhop 27 The Dutch Debate: Activism vs. Pragmatism Michal Onderco 39 French Perspectives on Disarmament and Deterrence Emmanuelle Maitre 51 Nuclear Deterrence and Arms Control: A NATO Perspective Jessica Cox and Joseph Dobbs 66 Defining the Needed Balance of Deterrence and Arms Control in Europe Anna Péczeli 74 Restoring the Balancing Act: Disarmament and Deterrence in the New Era Łukasz Kulesa 93 Rethinking the Impact of Emerging Technologies on Strategic Stability Andrea Gilli and Mauro Gilli 105 Artificial Intelligence and Deterrence: A View from Europe Laura Siddi 121 A Practitioner’s Perspective: Modern Deterrence and the U.S.–U.K. -

Proof of Reproduction of Salmon Returned to the Rhine System

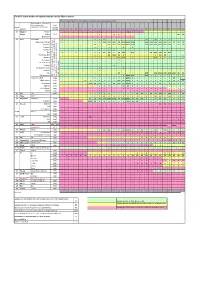

Proof of reproduction of salmon returned to the Rhine system Year of spawning proof (reproduction during the preceding autumn/winter) Project water - Selection of the most important First Countr tributaries (* no stocking) salmon y System stocking 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 D Wupper- Wupper / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / (X) / / / / / / / / / / X Dhünn Dhünn 1993 / / / / / / / / 0 / / X X / / / / / / / / / / / XX XX Eifgenbach / / / / / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / D Sieg Sieg NRW X / / / / / / X 0 XX / / / / / / / / XX / XX 0 0 0 / / / Agger (lower 30 km) X / / / / / / 0 0 XXX XXX XXX XX XXXX XXXX XXXX / / XXX XXX XXX XXX XXX XX XX XX XX Naafbach / / / / / / / XX 0 / XXX XXX XXX XXXX XXXX XXXX / / XXX XXX XXX XXXX XXX XXX 0 XX XX Pleisbach / / / / / / / 0 / / 0 / / X / X / / / / / / / / / / Hanfbach / / / / / / / / 0 / 0 X / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Bröl X / / X / / / 0 0 XX XX 0 XX XXX / XXX / / / XX XXX XXX XX XXX / / Homburger Bröl / / / / / / / 0 0 / XX XXX XX X / / / / / / 0 XX XX 0 / / 0 Waldbröl / / / / / / / 0 0 / 0 0 XXX XXX / 0 / / / / XXX 0 0 0 / / 0 Derenbach / / / / / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / Steinchesbach / / / / / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / Krabach / / / / / / / / / / / X / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Gierzhagener Bach / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / X / / / / / / / / / / / / Irsenbach / / / / / / / / 0 / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / / Sülz / / / / / / / 0 0 / / / XX / / / / / -

Die Natur in Der Luxemburger Moselregion Découvrir La Nature Dans La Région De La Experience the Natural Environment in the Erleben

Die Natur in der Luxemburger Moselregion Découvrir la nature dans la région de la Experience the natural environment in the erleben. Kanuausflüge auf Mosel und Sauer. Moselle luxembourgeoise. Excursions en Luxemburgish Moselle region. Canoe trips canoë sur la Moselle et la Sûre. on the Moselle and the Sauer. Das Kanuwandern als aktive Freizeitbeschäftigung steht jedem offen, La randonnée en canoë en tant qu’activité de loisirs est un sport Canoeing is an activity that can be enjoyed by everyone, be it in the ob auf der Mosel als gemächlicher Wanderfluss oder auf der Sauer mit ouvert à tous: que ce soit sur la Moselle, pour une excursion paisible, form of a leisurely excursion along the Mosel or a trip down the Sauer leichten Stromschnellen, ob jung oder alt, jeder kommt im Miseler- ou sur la Sûre avec ses légers rapides. Jeunes ou moins jeunes: dans la with its gentle rapids. Miselerland has something to offer for every- land auf seine Kosten! région du Miselerland, vous trouverez de quoi vous réjouir ! one whatever their age! DIE ANLEGESTELLEN LES POINTS D’ACCOSTAGE THE LANDING PLACES Dank den Anlegern entlang der Mosel und der Sauer, entscheiden Sie Grâce aux points d’accostage le long de la Moselle et de la Sûre, c’est Thanks to the landing places along the Mosel and the Sauer you can selbst an welchem Winzerort Sie einen Stopp einlegen. vous qui décidez dans quel village viticole vous allez faire une halte. choose in which viticulture village you like to stop. Entdecken Sie mit der ganzen Familie naturbelassene Seitentäler zu Découvrez à pied avec toute la famille les vallées adjacentes, qui You can discover the natural preserved lateral valleys by foot with Fuß, besichtigen Sie interessante Museen oder genießen Sie einfach ont conservé leur état naturel. -

Rare Earth Elements As Emerging Contaminants in the Rhine River, Germany and Its Tributaries

Rare earth elements as emerging contaminants in the Rhine River, Germany and its tributaries by Serkan Kulaksız A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geochemistry Approved, Thesis Committee _____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Michael Bau, Chair Jacobs University Bremen _____________________________________ Prof. Dr. Andrea Koschinsky Jacobs University Bremen _____________________________________ Dr. Dieter Garbe-Schönberg Universität Kiel Date of Defense: June 7th, 2012 _____________________________________ School of Engineering and Science TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER I – INTRODUCTION 1 1. Outline 1 2. Research Goals 4 3. Geochemistry of the Rare Earth Elements 6 3.1 Controls on Rare Earth Elements in River Waters 6 3.2 Rare Earth Elements in Estuaries and Seawater 8 3.3 Anthropogenic Gadolinium 9 3.3.1 Controls on Anthropogenic Gadolinium 10 4. Demand for Rare Earth Elements 12 5 Rare Earth Element Toxicity 16 6. Study Area 17 7. References 19 Acknowledgements 28 CHAPTER II – SAMPLING AND METHODS 31 1. Sample Preparation 31 1.1 Pre‐concentration 32 2. Methods 34 2.1 HCO3 titration 34 2.2 Ion Chromatography 34 2.3 Inductively Coupled Plasma – Optical Emission Spectrometer 35 2.4 Inductively Coupled Plasma – Mass Spectrometer 35 2.4.1 Method reliability 36 3. References 41 CHAPTER III – RARE EARTH ELEMENTS IN THE RHINE RIVER, GERMANY: FIRST CASE OF ANTHROPOGENIC LANTHANUM AS A DISSOLVED MICROCONTAMINANT IN THE HYDROSPHERE 43 Abstract 44 1. Introduction 44 2. Sampling sites and Methods 46 2.1 Samples 46 2.2 Methods 46 2.3 Quantification of REE anomalies 47 3. Results and Discussion 48 4. -

Welcome to the Rhine Cycle Route! from the SOURCE to the MOUTH: 1,233 KILOMETRES of CYCLING FUN with a RIVER VIEW Service Handbook Rhine Cycle Route

EuroVelo 15 EuroVelo 15 Welcome to the Rhine Cycle Route! FROM THE SOURCE TO THE MOUTH: 1,233 KILOMETRES OF CYCLING FUN WITH A RIVER VIEW Service handbook Rhine Cycle Route www.rhinecycleroute.eu 1 NEDERLAND Den Haag Utrecht Rotterdam Arnhem Hoek van Holland Kleve Emmerich am Rhein Dordrecht EuroVelo 15 Xanten Krefeld Duisburg Düsseldorf Neuss Köln BELGIË DEUTSCHLAND Bonn Koblenz Wiesbaden Bingen LUXEMBURG Mainz Mannheim Ludwigshafen Karlsruhe Strasbourg FRANCE Offenburg Colmar Schaff- Konstanz Mulhouse Freiburg hausen BODENSEE Basel SCHWEIZ Chur Andermatt www.rheinradweg.eu 2 Welcome to the Rhine Cycle Route – EuroVelo 15! FOREWORD Dear Cyclists, Discovering Europe on a bicycle – the Rhine Cycle Route makes it possible. It runs from the Alps to a North Sea beach and on its way links Switzerland, France, Germany and the Netherlands. This guide will point the way. Within the framework of the EU-funded “Demarrage” project, the Rhine Cycle Route has been trans- formed into a top tourism product. For the first time, the whole course has been signposted from the source to the mouth. Simply follow the EuroVelo15 symbol. The Rhine Cycle Route is also the first long distance cycle path to be certified in accordance with a new European standard. Testers belonging to the German ADFC cyclists organisation and the European Cyclists Federation have examined the whole course and evaluated it in accordance with a variety of criteria. This guide is another result of the European cooperation along the Rhine Cycle Route. We have broken up the 1233-kilometre course up into 13 sections and put together cycle-friendly accom- modation, bike stations, tourist information and sightseeing attractions – the basic package for an unforgettable cycle touring holiday. -

Case Study Rhine

International Commission for the Hydrology of the Rhine Basin Erosion, Transport and Deposition of Sediment - Case Study Rhine - Edited by: Manfred Spreafico Christoph Lehmann National coordinators: Alessandro Grasso, Switzerland Emil Gölz, Germany Wilfried ten Brinke, The Netherlands With contributions from: Jos Brils Martin Keller Emiel van Velzen Schälchli, Abegg & Hunzinger Hunziker, Zarn & Partner Contribution to the International Sediment Initiative of UNESCO/IHP Report no II-20 of the CHR International Commission for the Hydrology of the Rhine Basin Erosion, Transport and Deposition of Sediment - Case Study Rhine - Edited by: Manfred Spreafico Christoph Lehmann National coordinators: Alessandro Grasso, Switzerland Emil Gölz, Germany Wilfried ten Brinke, The Netherlands With contributions from: Jos Brils Martin Keller Emiel van Velzen Schälchli, Abegg & Hunzinger Hunziker, Zarn & Partner Contribution to the International Sediment Initiative of UNESCO/IHP Report no II-20 of the CHR © 2009, KHR/CHR ISBN 978-90-70980-34-4 Preface „Erosion, transport and deposition of sediment“ Case Study Rhine ________________________________________ Erosion, transport and deposition of sediment have significant economic, environmental and social impacts in large river basins. The International Sediment Initiative (ISI) of UNESCO provides with its projects an important contribution to sustainable sediment and water management in river basins. With the processing of exemplary case studies from large river basins good examples of sediment management prac- tices have been prepared and successful strategies and procedures will be made accessible to experts from other river basins. The CHR produced the “Case Study Rhine” in the framework of ISI. Sediment experts of the Rhine riparian states of Switzerland, Austria, Germany and The Netherlands have implemented their experiences in this publication. -

To Discover and Enjoy the Mosel Region

Discover and enjoy the Moselle countryside 2 At the top A warm welcome to the Moselle, Saar und Ruwer ... a countryside of superlatives awaiting your visit! It is here that winegrowers produce top international wines, it is here that the Romans founded the oldest city of Germany, it is here that you will find one of the most successful combinations of rich, ancient culture and countryside, which is sometimes gentle and sometimes spectacular. As far as the art of living is concerned, the proximity to France and Luxem- bourg inspires not only the cuisine of the Moselle region. There is hardly any other holiday region that has so many fascinating facets. 3 Winegrowers who cultivate steep hillsi INSIDE GERMANY the Moselle care and manual work. A winegro- has cut its way through deep wer must not suffer from vertigo gorges and countless meanders here! The steep slopes and terraces, into the mountains over a distance with their mild micro-climate and of more than 240 kilometres, until slate ground that stores the heat, it meets Father Rhine in Koblenz. are the ideal conditions for the Europe’s steepest vineyard, the Riesling grape, which produces the Bremmer Calmont, with a 68° uniquely delicate fruity and tangy slope, is situated in the largest wines along the Moselle, Saar and enclosed area of cliffs in the world: Ruwer. The dry Moselle wines, in roughly half of the Moselle vine- particular, that are cultivated by the yards, comprising around 10,000 5000 or so winegrowers, with a hectares in total, are cultivated in wealth of individual nuances, are 4 this way, which demands a lot of an excellent accompaniment to ides are heroes delicate dishes. -

Verlauf Der Linie 99 Ersatzverkehr S51/S52

Verlauf der Linie 99 Ersatzverkehr S51/S52 B 35 Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Asklepios Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Südpfalzklinik Germersheim Bellheimer Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Wald Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Queich Qu eich Queich Queich Queich Quei ch Queich Spiegelbach Queich Spiegelbach Queich In den Spiegelbach piegelbach S S piegelbach Spiegelbach Stöcken Spiegelbach Vorderwald Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spieg e l b ach Spiegelbach Spie g elbach Spiegelbach S piegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach egelbach Spi Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach B 9 Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Michelsbach elsbach ich M Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Spiegelbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Spiegelbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach ch a b Michels Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach M i chelsb a ch Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michels b ach Michelsbach Michelsbach Michelsbach ch a b s el Mich Michelsbach Michelsbach Herxheim Michelsbach Michelsbach h c a Michelsb