Size Related Variability in the Summer Diet of the Blackfin Tuna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROXIMATE and GENETIC ANALYSIS of BLACKFIN TUNA (T. Atlanticus)

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.03.366153; this version posted November 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. PROXIMATE AND GENETIC ANALYSIS OF BLACKFIN TUNA (T. atlanticus). Yuridia M. Núñez-Mata1, Jesse R. Ríos Rodríguez 1, Adriana L. Perales-Torres 1, Xochitl F. De la Rosa-Reyna2, Jesús A. Vázquez-Rodríguez 3, Nadia A. Fernández-Santos2, Humberto Martínez Montoya 1 * 1 Unidad Académica Multidisciplinaria Reynosa Aztlán – Universidad Autónoma de Tamaulipas. Reynosa, Tamaulipas. 2 Centro de Biotecnología Genómica – Instituto Politécnico Nacional. Reynosa, Tamaulipas. 3 Centro de Investigación en Salud Pública y Nutrición – Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. Monterrey, Nuevo León. *Correspondence: [email protected] ORCID: 0000-0003-3228-0054 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.11.03.366153; this version posted November 4, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. ABSTRACT The tuna meat is a nutritious food that possesses high content of protein, its low content of saturated fatty acids makes it a high demand food in the world. The Thunnus genus is composed of eight species, albacore (T. alalunga), bigeye (T. obesus), long tail tuna (T. tonggol), yellowfin tuna (T. albacares), pacific bluefin tuna (T. orientalis), bluefin tuna (T. maccoyii), Atlantic bluefin tuna ( T. thynnus) and blackfin tuna (T. atlanticus). The blackfin tuna (BFT) (Thunnus atlanticus) represent the smallest species within the Thunnus genus. -

A Global Valuation of Tuna an Update February 2020 (Final)

Netting Billions: a global valuation of tuna an update February 2020 (Final) ii Report Information This report has been prepared with the financial support of The Pew Charitable Trusts. The views expressed in this study are purely those of the authors. The content of this report may not be reproduced, or even part thereof, without explicit reference to the source. Citation: Macfadyen, G., Huntington, T., Defaux, V., Llewellin, P., and James, P., 2019. Netting Billions: a global valuation of tuna (an update). Report produced by Poseidon Aquatic Resources Management Ltd. Client: The Pew Charitable Trusts Version: Final Report ref: 1456-REG/R/02/A Date issued: 7 February 2020 Acknowledgements: Our thanks to the following consultants who assisted with data collection for this study: Richard Banks, Sachiko Tsuji, Charles Greenwald, Heiko Seilert, Gilles Hosch, Alicia Sanmamed, Anna Madriles, Gwendal le Fol, Tomasz Kulikowski, and Benoit Caillart. 7 February 2020 iii CONTENTS 1. BACKGROUND AND INTRODUCTION ................................................................... 1 2. STUDY METHODOLOGY ......................................................................................... 3 3. TUNA LANDINGS ..................................................................................................... 5 3.1 METHODOLOGICAL ISSUES ....................................................................................... 5 3.2 RESULTS ............................................................................................................... -

Genetic Species Identification – SBT Market Presence in China: Draft Final Report To

CCSBT-ESC/1409/18CCSBT-CC/1610/23 OCEANS AND ATMOSPHERE DRAFT Final Report to TRAFFIC International Genetic species identification – SBT market presence in China. Campbell Davies, Jessica Farley, Peta Hill, Matt Lansdell and Peter Grewe Report to TRAFFIC and CCSBT Secretariat 2 October 2016 Copyright © Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation 2016. To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO. Important disclaimer CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. CSIRO is committed to providing web accessible content wherever possible. If you are having difficulties with accessing this document please contact [email protected]. Acknowledgments Our thanks go to Joyce Wu and TRAFFIC for providing the tissue samples and associated data. This work was funded by the CCSBT and CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere. -

Download the Report

February 2006 WHAT’S ON THE HOOK? MERCURY LEVELS AND FISH CONSUMPTION SURVEYED AT A GULF OF MEXICO FISHING RODEO Kimberly Warner Jacqueline Savitz ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS: We wish to thank the organizers of the 73rd Annual Deep Sea Fishing Rodeo, particularly Pat Troup, Mike Thomas, and the anglers, the National Seafood Inspection Lab, the Dauphin Island Sea Lab, and the invaluable assistance of Dr. Bob Shipp, Dr. Sean Powers, Melissa Powers, the hard working DISL graduate students and Oceana staff, including Gib Brogan, Phil Kline, Mike Hirshfield, Suzanne Garrett, Bianca Delille, Sam Haswell, Heather Ryan and Dawn Winalski. TABLE OF CONTENTS: 4 Executive Summary 5 Major Findings 6 Recommendations 8 Introduction 10 Results 10 Mercury Levels 14 Fish Consumption 16 Fish Consumption and Mercury Levels 18 Recommendations 19 Methods 20 Appendices 20 Table A1 Raw Mercury Data 25 Table A2 Gulf Comparisons 30 Table A3 US EPA Risk-based Consumption Guideline 31 Endnotes EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: In the past few years, seafood lovers have become increasingly concerned about mercury levels in Gulf of Mexico fish. Unfortunately, anglers have not had the in- formation they need to help them decide which fish may be safer to eat, despite the fact that recreational anglers and their families typically eat more fish than the average population. In fact, recent studies have found that people who live in coastal areas of the United States have higher levels of mercury in their blood than residents from inland areas.1 The purpose of this report is to help provide infor- mation to recreational anglers in the Gulf of Mexico on which fish may be higher in mercury than others, which would be safer to eat, and which species are in need of further monitoring. -

SMALL TUNAS SMT-1. Generalities the Species Under The

2019 SCRS REPORT 9.12 SMT – SMALL TUNAS SMT-1. Generalities The species under the Small Tunas Species Group include the following tuna and tuna-like species: – BLF Blackfin tuna (Thunnus atlanticus) – BLT Bullet tuna (Auxis rochei) – BON Atlantic bonito (Sarda sarda) – BOP Plain bonito (Orcynopsis unicolor) – BRS Serra Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus brasiliensis) – CER Cero (Scomberomorus regalis) – FRI Frigate tuna (Auxis thazard) – KGM King mackerel (Scomberomorus cavalla) – LTA Little tunny (Euthynnus alletteratus) – MAW West African Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus tritor) – SSM Atlantic Spanish mackerel (Scomberomorus maculatus) – WAH Wahoo (Acanthocybium solandri) – DOL Dolphinfish (Coryphaena hippurus) Knowledge on the biology and fishery of small tunas is very fragmented. Furthermore, the quality of the knowledge varies according to the species concerned. This is due in large part to the fact that these species are often perceived to have little economic importance compared to other tunas and tuna-like species, and owing to the difficulties in conducting sampling of the landings from artisanal fisheries, which constitute a high proportion of the fisheries exploiting small tuna resources. The large industrial fleets often discard small tuna catches at sea or sell them on local markets mixed with other by-catches, especially in Africa. The amount caught is rarely reported in logbooks; however observer programs from purse seine fleets have recently provided estimates of catches of small tunas. Small tuna species can reach high levels of catches and values in some years and have a very high relevance from a social and economic point of view, because they are important for many coastal communities in all areas and a main source of food. -

C1. Tuna and Tuna-Like Species

163 C1. TUNA AND TUNA-LIKE SPECIES exceptional quality reached US$500 per kg and by Jacek Majkowski * more recently even more, but such prices referring to very few single fish do not reflect the INTRODUCTION situation with the market. Bigeye are also well priced on the sashimi markets. Although The sub-order Scombroidei is usually referred to yellowfin are also very popular on these markets, as tuna and tuna-like species (Klawe, 1977; the prices they bring are much lower. For Collette and Nauen, 1983; Nakamura, 1985). It is canning, albacore fetch the best prices due to composed of tunas (sometimes referred to as true their white meat, followed by yellowfin and tunas), billfishes and other tuna-like species. skipjack for which fishermen are paid much less They include some of the largest and fastest than US$1 per kg. The relatively low prices of fishes in the sea. canning-quality fish are compensated by their The tunas (Thunnini) include the most very large catches, especially in the case of economically important species referred to as skipjack and yellowfin. Longtail tuna principal market tunas because of their global (T. tonggol) is becoming increasingly important economic importance and their intensive for canning and the subject of substantial international trade for canning and sashimi (raw international trade. The consumption of tuna and fish regarded as delicacy in Japan and tuna-like species in forms other than canned increasingly, in several other countries). In fact, products and sashimi is increasing. the anatomy of some tuna species seems to have The tunas other than the principal market species been purpose-designed for canning and loining. -

SYNOPSIS of BIOLOGICAL DATA on the BLACKFIN TUNA Thunnus Atlanticus (Lesson) 1830 (WESTERN ATLANTIC)

Species Synopsis No. 25 FAO Fisheries Biology Synopsis No, 68 FIb/S68 (Distribution restricted) SAST - Tuna SYNOPSIS OF BIOLOGICAL DATA ON THE BLACKFIN TUNA Thunnus atlanticus (Lesson) 1830 (WESTERN ATLANTIC) Exposé synoptique sur la biologie du thon à nageoires noires Thunnus atlanticus (Lessoñ) 1830 (Atlantique Ouest) Sinopsis sobre la biología del atn de aleta negra Thunnus atlanticus (Lesson) 1830 (Atlántico Occidental) Prepared by C, P, IDYLL and DONALD DE SYLVA Institute of Marine Science University of Miami Miami, Florida, U. S. A, EISHERIES DIVISION, BIOLOGY BRANCH OOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS tome, 1963 761 Fb/S6& Tuna 1:1 i IDENTITY at vertical of the origin of the second dorsal fin in a 443 mm. fish measuring 2.75 nun, high 1,1 Taxonomy and 2,6 ulm. long. Corselet small, inconspic- uous, largely over the base of the pectoral. 1.1.1 Definition "Lateral line complete, slightly wavy, Phylum Vertebrata not very high anteriorly, becoming median in Subphylum Craniata position only on the posterior caudal peduncle. Supe rc lass Gnathost omata Series Pisces "Head conical, 3.15 to 3.6 in standard Class Teleostomj length, the lower profile slightly more con- Subclass Actinopterygij vex than the upper. Snout not especially Order sharp, 2.9 to 3.25 in the head length. Eye Suborder -Scombroidej large, obliquely set in head, 4,35 to 6 in Family Scombridae head length (5.3 to 6 in fish over 380 mm,); Genus Thunnus South adipose eyelid very smell; interorbital space Species atlanticus (Lesson) convex, 2.6 to 3,6. 1.1.2Description "Posterior nostril an elongate vertical slit, its length slightly less than one-half Genus Thunnus the eye diameter. -

8.2 the Significance of Ocean Deoxygenation for Open Ocean Tunas and Billfishes Shirley Leung,K

8.2 The significance of ocean deoxygenation for open ocean tunas and billfishes Shirley Leung,K. A. S. Mislan, Barbara Muhling and Richard Brill 8.2 The significance of ocean deoxygenation for open ocean tunas and billfishes Shirley Leung1,*, K. A. S. Mislan1,2, Barbara Muhling3,4 and Richard Brill5 1 School of Oceanography, University of Washington, USA. Email : [email protected] 2 eScience Institute, University of Washington, USA 3 University of California Santa Cruz, Santa Cruz, CA, USA 4 National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Marine Fisheries Service, Southwest Fisheries Science Center, La Jolla, CA, USA 5 Virginia Institute of Marine Science, Gloucester Point, VA, USA Summary • Tunas and billfishes should be especially sensitive to low ambient oxygen conditions given their high metabolic rates as well as the large differences between their resting and maximum metabolic rates. Although there are many behavioural similarities among the different species, there are also clear and demonstrable differences in growth rates, maximum adult size, physiological abilities, low-oxygen tolerances, and preferred environmental conditions. • Climate change is projected to alter oxygen concentrations throughout the open ocean, with most regions undergoing decreases due to a slowdown in ocean ventilation and a decline in surface oxygen solubility. Between 200 and 700 m depth (a vertical range including depths to which tunas and billfishes commonly descend to forage), the greatest and most certain decreases in oxygen concentrations are projected to occur in the North Pacific and much of the Southern Ocean, while the smallest and least certain changes are projected to occur within the tropical Pacific Ocean. -

Blackfin Tuna Thunnus Atlanticus and Little Tunny Euthynnus Alletteratus

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks HCNSO Student Theses and Dissertations HCNSO Student Work 12-12-2014 Reproductive parameters of two coastal pelagic fishes off southeast Florida: Blackfin unT a Thunnus atlanticus and Little unnT y Euthynnus alletteratus Sonia Ahrabi-Nejad Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd Part of the Marine Biology Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Sonia Ahrabi-Nejad. 2014. Reproductive parameters of two coastal pelagic fishes off southeast Florida: Blackfin Tuna Thunnus atlanticus and Little Tunny Euthynnus alletteratus. Master's thesis. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, Oceanographic Center. (25) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd/25. This Thesis is brought to you by the HCNSO Student Work at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in HCNSO Student Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOVA SOUTHEASTERN UNIVERSITY OCEANOGRAPHIC CENTER Reproductive parameters of two coastal pelagic fishes off southeast Florida: Blackfin Tuna Thunnus atlanticus and Little Tunny Euthynnus alletteratus. By Sonia Ahrabi-Nejad Submitted to the Faculty of Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science with a specialty in: Marine Biology Nova Southeastern University -

Blackfin Tuna (Thunnus Atlanticus) in the Venezuelan Fisheries

SCRS/2011/122 Collect. Vol. Sci. Pap. ICCAT, 68(3): 1253-1260 (2012) BLACKFIN TUNA (THUNNUS ATLANTICUS) IN THE VENEZUELAN FISHERIES F. Arocha1, A. Barrios1, J. Marcano2, and X. Gutierrez2 SUMMARY Catches from 1988 to 2009 for blackfin tuna (Thunnus atlanticus) from the Venezuelan industrial surface fleets and the small scale fisheries were reviewed, and catch and effort seasonality by fishery was analyzed. Standardized catch rates were estimated for the industrial surface fleets using Generalized Linear Model techniques. Size distribution from the industrial surface fleets by year and month were analyzed, and cumulative seasonal spatial distribution was discussed. RÉSUMÉ Les captures de thons à nageoires noires (Thunnus atlanticus) réalisées entre 1988 et 2009 par les flottilles industrielles de surface et les pêcheries de petits métiers du Venezuela ont été examinées, et la saisonnalité de la prise et de l'effort a été analysée par pêcherie. Des taux de capture standardisés ont été estimés pour les flottilles de surface industrielles à l'aide de techniques de modèle linéaire généralisé. La distribution des tailles des flottilles de surface industrielles par année et mois a été analysée, et la distribution spatiale saisonnière cumulative a été discutée. RESUMEN Se revisaron las capturas desde 1988 a 2009 para el atún aleta negra (Thunnus atlanticus) de las flotas de superficie industriales y de las pesquerías de pequeña escala de Venezuela, y se analizó la estacionalidad de la captura y del esfuerzo por pesquería. Se estimaron las tasas de captura estandarizadas para las flotas de superficie industriales utilizando técnicas del modelo lineal generalizado. Se analizaron las distribuciones por tallas de las flotas de superficie industriales por año y mes, y se debatió la distribución espacial estacional acumulativa. -

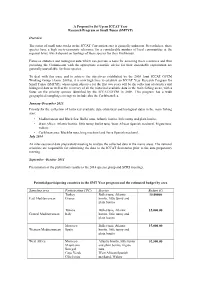

A Proposal to Set up an ICCAT Year Research Program Or Small Tunas (SMTYP) Overview the Status of Small Tuna Stocks in the ICCAT

A Proposal to Set Up an ICCAT Year Research Program or Small Tunas (SMTYP) Overview The status of small tuna stocks in the ICCAT Convention area is generally unknown. Nevertheless, these species have a high socio-economic relevance for a considerable number of local communities at the regional level, which depend on landings of these species for their livelihoods. Fisheries statistics and biological data which can provide a basis for assessing these resources and thus providing the Commission with the appropriate scientific advice for their sustainable exploitation are generally unavailable for these species. To deal with this issue and to achieve the objectives established by the 2008 Joint ICCAT GFCM Working Group (Anon. 2009a), it is now high time to establish an ICCAT Year Research Program for Small Tunas (SMTYP), whose main objective for the first two years will be the collection of statistics and biological data as well as the recovery of all the historical available data in the main fishing areas, with a focus on the priority species identified by the ICCAT/GFCM in 2008. This program has a wide geographical sampling coverage to include also the Caribbean Sea. January-December 2013: Priority for the collection of historical available data (statistical and biological data) in the main fishing area: • Mediterranean and Black Sea: Bullet tuna, Atlantic bonito, little tunny and plain bonito; • West Africa: Atlantic bonito, little tunny, bullet tuna, West African Spanish mackerel, frigate tuna, wahoo; • Caribbean area: Blackfin tuna, king mackerel and Serra Spanish mackerel. July 2014 An inter-sessional data preparatory meeting to analyse the collected data in the mains areas. -

Family: Scombridae; Tribe: Thunnini) Early Life Stages in the Oceanic Gulf of Mexico Nina Pruzinsky Nova Southeastern University, [email protected]

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks HCNSO Student Theses and Dissertations HCNSO Student Work 5-2-2018 Identification and spatiotemporal dynamics of tuna (Family: Scombridae; Tribe: Thunnini) early life stages in the oceanic Gulf of Mexico Nina Pruzinsky Nova Southeastern University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd Part of the Marine Biology Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons Share Feedback About This Item NSUWorks Citation Nina Pruzinsky. 2018. Identification and spatiotemporal dynamics of tuna (Family: Scombridae; Tribe: Thunnini) early life stages in the oceanic Gulf of Mexico. Master's thesis. Nova Southeastern University. Retrieved from NSUWorks, . (472) https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd/472. This Thesis is brought to you by the HCNSO Student Work at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in HCNSO Student Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thesis of Nina Pruzinsky Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science M.S. Marine Biology Nova Southeastern University Halmos College of Natural Sciences and Oceanography May 2018 Approved: Thesis Committee Major Professor: Tracey Sutton Committee Member: David Kerstetter Committee Member: Jay Rooker This thesis is available at NSUWorks: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_stuetd/472 HALMOS COLLEGE OF NATURAL SCIENCES AND OCEANOGRAPHY IDENTIFICATION AND SPATIOTEMPORAL DYNAMICS OF TUNA (FAMILY: SCOMBRIDAE; TRIBE: THUNNINI) EARLY LIFE STAGES IN THE OCEANIC GULF OF MEXICO By Nina M. Pruzinsky Submitted to the Faculty of Halmos College of Natural Sciences and Oceanography in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science with a specialty in: Marine Biology Nova Southeastern University May 2, 2018 Thesis of Nina M.