Rediscovering Giuseppe Verdi's Messa Da Requiem

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

18400 Cmp.Pdf

® I GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU , Temporada 1996-97 CONSORCI DEL GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU GENERALITAT DE CATALUNYA � AJUNTAMENT DE BARCELONA MINISTERIO DE CULTURA AJORlCA DIPUTACIÓ DE BARCELONA Joyas y Perlas Jewellery & Pearls ® II harhiere di Siviglia Òpera còmica en dos actes Llibret de Cesare Sterhini, sobre el text de Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais Música de Gioacchino Rossini (amb sobretitulat) Teatre Victòria Dilluns, 16 de juny, 21 h, funció núm. 25, torn A Dijous, 19 de juny, 21 h, funció núm. 26, torn E Diumenge, 22 de juny, 17 h, funció núm. 27, torn T Dimecres, 25 de juny, 21 h, funció núm. 28, torn D Dissabte, 28 de juny, 21 h, funció núm. 29, torn e Dilluns, 30 de juny, 21 h, funció núm. 30, torn B GRAN TEATRE DEL LICEU - 150e Aniversari El Liceu fa 150 anys. Moltes felicitats a tothom que ho ha fet possible. junts en farem molts més! Societat, Consorci i Fundació del Gran Teatre del Liceu. IL·LUSIONATS AMB EL NOU LICEU. 1 8 4 7 / 1 997 IL·LUSIONATS AMB EL NOU LICEU. Generalitat de Catalunya, Ministerio de Cultura, Ajuntament de Barcelona, Diputació de Barcelona, Societat del Gran Teatre del Liceu i Consell de Mecenatge Autopistas C.E.SA II BILBAO BANCO VIZCAYA ARGENTARIA � w w w # BANCACATI'JANA u u u Banco II ...J Santander ...J ...J fiii· Central Hispano � BanesfQ Borsa de Barcelona ::J ::J ::J O O Cambra Oficial O de Comerç Z z Indústria i Navegació Z - de Barcelona ...J ...J ...J : R w w W ctlV[ •••• lli!�IJf!YA TURISME DE �f� RIJiO - BARCELONA i VINSA - , �Dragados .- w � Erkimia gasNajural l l l e( e( e( 11 z winterthur Z Z e PHILIPS Grupo Endesa O O O de Barcelona c� j\igües Telefónica ...J ...J ...J A Thvssen Boettlcher ...J ...J ...J MANTENIMIENTOS ESPECIALES IIHELLI WAAGNE�1ïl RUBENS, S.A. -

Mozart Magic Philharmoniker

THE T A R S Mass, in C minor, K 427 (Grosse Messe) Barbara Hendricks, Janet Perry, sopranos; Peter Schreier, tenor; Benjamin Luxon, bass; David Bell, organ; Wiener Singverein; Herbert von Karajan, conductor; Berliner Mozart magic Philharmoniker. Mass, in C major, K 317 (Kronungsmesse) (Coronation) Edith Mathis, soprano; Norma Procter, contralto...[et al.]; Rafael Kubelik, Bernhard Klee, conductors; Symphonie-Orchester des on CD Bayerischen Rundfunks. Vocal: Opera Così fan tutte. Complete Montserrat Caballé, Ileana Cotrubas, so- DALENA LE ROUX pranos; Janet Baker, mezzo-soprano; Nicolai Librarian, Central Reference Vocal: Vespers Vesparae solennes de confessore, K 339 Gedda, tenor; Wladimiro Ganzarolli, baritone; Kiri te Kanawa, soprano; Elizabeth Bainbridge, Richard van Allan, bass; Sir Colin Davis, con- or a composer whose life was as contralto; Ryland Davies, tenor; Gwynne ductor; Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal pathetically brief as Mozart’s, it is Howell, bass; Sir Colin Davis, conductor; Opera House, Covent Garden. astonishing what a colossal legacy F London Symphony Orchestra and Chorus. Idomeneo, K 366. Complete of musical art he has produced in a fever Anthony Rolfe Johnson, tenor; Anne of unremitting work. So much music was Sofie von Otter, contralto; Sylvia McNair, crowded into his young life that, dead at just Vocal: Masses/requiem Requiem mass, K 626 soprano...[et al.]; Monteverdi Choir; John less than thirty-six, he has bequeathed an Barbara Bonney, soprano; Anne Sofie von Eliot Gardiner, conductor; English Baroque eternal legacy, the full wealth of which the Otter, contralto; Hans Peter Blochwitz, tenor; soloists. world has yet to assess. Willard White, bass; Monteverdi Choir; John Le nozze di Figaro (The marriage of Figaro). -

ARSC Journal

A Discography of the Choral Symphony by J. F. Weber In previous issues of this Journal (XV:2-3; XVI:l-2), an effort was made to compile parts of a composer discography in depth rather than breadth. This one started in a similar vein with the realization that SO CDs of the Beethoven Ninth Symphony had been released (the total is now over 701). This should have been no surprise, for writers have stated that the playing time of the CD was designed to accommodate this work. After eighteen months' effort, a reasonably complete discography of the work has emerged. The wonder is that it took so long to collect a body of information (especially the full names of the vocalists) that had already been published in various places at various times. The Japanese discographers had made a good start, and some of their data would have been difficult to find otherwise, but quite a few corrections and additions have been made and some recording dates have been obtained that seem to have remained 1.Dlpublished so far. The first point to notice is that six versions of the Ninth didn't appear on the expected single CD. Bl:lhm (118) and Solti (96) exceeded the 75 minutes generally assumed (until recently) to be the maximum CD playing time, but Walter (37), Kegel (126), Mehta (127), and Thomas (130) were not so burdened and have been reissued on single CDs since the first CD release. On the other hand, the rather short Leibowitz (76), Toscanini (11), and Busch (25) versions have recently been issued with fillers. -

Libretto Nabucco.Indd

Nabucco Musica di GIUSEPPE VERDI major partner main sponsor media partner Il Festival Verdi è realizzato anche grazie al sostegno e la collaborazione di Soci fondatori Consiglio di Amministrazione Presidente Sindaco di Parma Pietro Vignali Membri del Consiglio di Amministrazione Vincenzo Bernazzoli Paolo Cavalieri Alberto Chiesi Francesco Luisi Maurizio Marchetti Carlo Salvatori Sovrintendente Mauro Meli Direttore Musicale Yuri Temirkanov Segretario generale Gianfranco Carra Presidente del Collegio dei Revisori Giuseppe Ferrazza Revisori Nicola Bianchi Andrea Frattini Nabucco Dramma lirico in quattro parti su libretto di Temistocle Solera dal dramma Nabuchodonosor di Auguste Anicet-Bourgeois e Francis Cornu e dal ballo Nabucodonosor di Antonio Cortesi Musica di GIUSEPPE V ERDI Mesopotamia, Tavoletta con scrittura cuneiforme La trama dell’opera Parte prima - Gerusalemme All’interno del tempio di Gerusalemme, i Leviti e il popolo lamen- tano la triste sorte degli Ebrei, sconfitti dal re di Babilonia Nabucco, alle porte della città. Il gran pontefice Zaccaria rincuora la sua gente. In mano ebrea è tenuta come ostaggio la figlia di Nabucco, Fenena, la cui custodia Zaccaria affida a Ismaele, nipote del re di Gerusalemme. Questi, tuttavia, promette alla giovane di restituirle la libertà, perché un giorno a Babilonia egli stesso, prigioniero, era stato liberato da Fe- nena. I due innamorati stanno organizzando la fuga, quando giunge nel tempio Abigaille, supposta figlia di Nabucco, a comando di una schiera di Babilonesi. Anch’essa è innamorata di Ismaele e minaccia Fenena di riferire al padre che ella ha tentato di fuggire con uno stra- niero; infine si dichiara disposta a tacere a patto che Ismaele rinunci alla giovane. -

Sir John Eliot Gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:Q L’Istesso Tempo— Con Moto Elgar in the South (Alassio), Op

Program OnE HundrEd TwEnTIETH SEASOn Chicago Symphony orchestra riccardo muti Music director Pierre Boulez Helen regenstein Conductor Emeritus Yo-Yo ma Judson and Joyce Green Creative Consultant Global Sponsor of the CSO Thursday, January 20, 2011, at 8:00 Saturday, January 22, 2011, at 8:00 Sir John Eliot gardiner Conductor Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements = 160 Andante—Interlude:q L’istesso tempo— Con moto Elgar In the South (Alassio), Op. 50 IntErmISSIon Bartók Concerto for Orchestra Introduzione: Andante non troppo—Allegro vivace Giuoco delle coppie: Allegro scherzando Elegia: Andante non troppo Intermezzo interrotto: Allegretto Finale: Presto Steinway is the official piano of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. This program is partially supported by grants from the Illinois Arts Council, a state agency, and the National Endowment for the Arts. CommEntS by PHILLIP HuSCHEr Igor Stravinsky Born June 18, 1882, Oranienbaum, Russia. Died April 6, 1971, New York City. Symphony in three movements o composer has given us more Stravinsky is again playing word Nperspectives on a “symphony” games. (And, perhaps, as has than Stravinsky. He wrote a sym- been suggested, he used the term phony at the very beginning of his partly to placate his publisher, who career (it’s his op. 1), but Stravinsky reminded him, after the score was quickly became famous as the finished, that he had been com- composer of three ballet scores missioned to write a symphony.) (Petrushka, The Firebird, and The Rite Then, at last, a true symphony: in of Spring), and he spent the next few 1938, Mrs. Robert Woods Bliss, years composing for the theater and together with Mrs. -

Michael Morgan Playlist

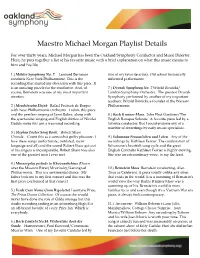

Maestro Michael Morgan Playlist Details For over thirty years, Michael Morgan has been the Oakland Symphony Conductor and Music Director. Here, he puts together a list of his favorite music with a brief explanation on what this music means to him and his life. 1.) Mahler Symphony No. 7. Leonard Bernstein two of my favorite artists. Old school historically conducts New York Philharmonic. This is the informed performance. recording that started my obsession with this piece. It is an amazing puzzle for the conductor. And, of 7.) Dvorak Symphony No. 7 Witold Rowicki/ course, Bernstein was one of my most important London Symphony Orchestra. The greatest Dvorak mentors. Symphony performed by another of my important teachers: Witold Rowicki, a founder of the Warsaw 2.) Mendelssohn Elijah. Rafael Frubeck de Burgos Philharmonic. with New Philharmonia Orchestra. I adore this piece and the peerless singing of Janet Baker, along with 8.) Bach B minor Mass. John Eliot Gardiner/The the spectacular singing and English diction of Nicolai English Baroque Soloists. A favorite piece led by a Gedda make this just a treasured recording. favorite conductor. But I could endorse any of a number of recordings by early music specialists. 3.) Stephen Foster Song Book. Robert Shaw Chorale. Count this as a somewhat guilty pleasure. I 9.) Schumann Frauenlieben und Leben. Any of the love these songs (unfortunate, outdated, racist recordings by Kathleen Ferrier. The combination of language and all) and the sound Robert Shaw got out Schumann's heartfelt song cycle and the great of his singers is incomparable. Robert Shaw was also English Contralto Kathleen Ferrier is highly moving. -

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details

Verdi Week on Operavore Program Details Listen at WQXR.ORG/OPERAVORE Monday, October, 7, 2013 Rigoletto Duke - Luciano Pavarotti, tenor Rigoletto - Leo Nucci, baritone Gilda - June Anderson, soprano Sparafucile - Nicolai Ghiaurov, bass Maddalena – Shirley Verrett, mezzo Giovanna – Vitalba Mosca, mezzo Count of Ceprano – Natale de Carolis, baritone Count of Ceprano – Carlo de Bortoli, bass The Contessa – Anna Caterina Antonacci, mezzo Marullo – Roberto Scaltriti, baritone Borsa – Piero de Palma, tenor Usher - Orazio Mori, bass Page of the duchess – Marilena Laurenza, mezzo Bologna Community Theater Orchestra Bologna Community Theater Chorus Riccardo Chailly, conductor London 425846 Nabucco Nabucco – Tito Gobbi, baritone Ismaele – Bruno Prevedi, tenor Zaccaria – Carlo Cava, bass Abigaille – Elena Souliotis, soprano Fenena – Dora Carral, mezzo Gran Sacerdote – Giovanni Foiani, baritone Abdallo – Walter Krautler, tenor Anna – Anna d’Auria, soprano Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra Vienna State Opera Chorus Lamberto Gardelli, conductor London 001615302 Aida Aida – Leontyne Price, soprano Amneris – Grace Bumbry, mezzo Radames – Placido Domingo, tenor Amonasro – Sherrill Milnes, baritone Ramfis – Ruggero Raimondi, bass-baritone The King of Egypt – Hans Sotin, bass Messenger – Bruce Brewer, tenor High Priestess – Joyce Mathis, soprano London Symphony Orchestra The John Alldis Choir Erich Leinsdorf, conductor RCA Victor Red Seal 39498 Simon Boccanegra Simon Boccanegra – Piero Cappuccilli, baritone Jacopo Fiesco - Paul Plishka, bass Paolo Albiani – Carlos Chausson, bass-baritone Pietro – Alfonso Echevarria, bass Amelia – Anna Tomowa-Sintow, soprano Gabriele Adorno – Jaume Aragall, tenor The Maid – Maria Angels Sarroca, soprano Captain of the Crossbowmen – Antonio Comas Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Chorus of the Gran Teatre del Liceu, Barcelona Uwe Mund, conductor Recorded live on May 31, 1990 Falstaff Sir John Falstaff – Bryn Terfel, baritone Pistola – Anatoli Kotscherga, bass Bardolfo – Anthony Mee, tenor Dr. -

Otello Program

GIUSEPPE VERDI otello conductor Opera in four acts Gustavo Dudamel Libretto by Arrigo Boito, based on production Bartlett Sher the play by William Shakespeare set designer Thursday, January 10, 2019 Es Devlin 7:30–10:30 PM costume designer Catherine Zuber Last time this season lighting designer Donald Holder projection designer Luke Halls The production of Otello was made possible by revival stage director Gina Lapinski a generous gift from Jacqueline Desmarais, in memory of Paul G. Desmarais Sr. The revival of this production is made possible by a gift from Rolex general manager Peter Gelb jeanette lerman-neubauer music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin 2018–19 SEASON The 345th Metropolitan Opera performance of GIUSEPPE VERDI’S otello conductor Gustavo Dudamel in order of vocal appearance montano a her ald Jeff Mattsey Kidon Choi** cassio lodovico Alexey Dolgov James Morris iago Željko Lučić roderigo Chad Shelton otello Stuart Skelton desdemona Sonya Yoncheva This performance is being broadcast live on Metropolitan emilia Opera Radio on Jennifer Johnson Cano* SiriusXM channel 75 and streamed at metopera.org. Thursday, January 10, 2019, 7:30–10:30PM KEN HOWARD / MET OPERA Stuart Skelton in Chorus Master Donald Palumbo the title role and Fight Director B. H. Barry Sonya Yoncheva Musical Preparation Dennis Giauque, Howard Watkins*, as Desdemona in Verdi’s Otello J. David Jackson, and Carol Isaac Assistant Stage Directors Shawna Lucey and Paula Williams Stage Band Conductor Gregory Buchalter Prompter Carol Isaac Italian Coach Hemdi Kfir Met Titles Sonya Friedman Children’s Chorus Director Anthony Piccolo Assistant Scenic Designer, Properties Scott Laule Assistant Costume Designers Ryan Park and Wilberth Gonzalez Scenery, properties, and electrical props constructed and painted in Metropolitan Opera Shops Costumes executed by Metropolitan Opera Costume Department; Angels the Costumiers, London; Das Gewand GmbH, Düsseldorf; and Seams Unlimited, Racine, Wisconsin Wigs and Makeup executed by Metropolitan Opera Wig and Makeup Department This production uses strobe effects. -

Verdi Otello

VERDI OTELLO RICCARDO MUTI CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA ALEKSANDRS ANTONENKO KRASSIMIRA STOYANOVA CARLO GUELFI CHICAGO SYMPHONY CHORUS / DUAIN WOLFE Giuseppe Verdi (1813-1901) OTELLO CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA RICCARDO MUTI 3 verdi OTELLO Riccardo Muti, conductor Chicago Symphony Orchestra Otello (1887) Opera in four acts Music BY Giuseppe Verdi LIBretto Based on Shakespeare’S tragedy Othello, BY Arrigo Boito Othello, a Moor, general of the Venetian forces .........................Aleksandrs Antonenko Tenor Iago, his ensign .........................................................................Carlo Guelfi Baritone Cassio, a captain .......................................................................Juan Francisco Gatell Tenor Roderigo, a Venetian gentleman ................................................Michael Spyres Tenor Lodovico, ambassador of the Venetian Republic .......................Eric Owens Bass-baritone Montano, Otello’s predecessor as governor of Cyprus ..............Paolo Battaglia Bass A Herald ....................................................................................David Govertsen Bass Desdemona, wife of Otello ........................................................Krassimira Stoyanova Soprano Emilia, wife of Iago ....................................................................BarBara DI Castri Mezzo-soprano Soldiers and sailors of the Venetian Republic; Venetian ladies and gentlemen; Cypriot men, women, and children; men of the Greek, Dalmatian, and Albanian armies; an innkeeper and his four servers; -

The Worlds of Rigoletto: Verdiâ•Žs Development of the Title Role in Rigoletto

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2008 The Worlds of Rigoletto Verdi's Development of the Title Role in Rigoletto Mark D. Walters Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MUSIC THE WORLDS OF RIGOLETTO VERDI’S DEVELOPMENT OF THE TITLE ROLE IN RIGOLETTO By MARK D. WALTERS A Treatise submitted to the College of Music in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music Degree Awarded: Spring Semester, 2008 The members of the Committee approve the Treatise of Mark D. Walters defended on September 25, 2007. Douglas Fisher Professor Directing Treatise Svetla Slaveva-Griffin Outside Committee Member Stanford Olsen Committee Member The Office of Graduate Studies has verified and approved the above named committee members. ii I would like to dedicate this treatise to my parents, Dennis and Ruth Ann Walters, who have continually supported me throughout my academic and performing careers. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Douglas Fisher, who guided me through the development of this treatise. As I was working on this project, I found that I needed to raise my levels of score analysis and analytical thinking. Without Professor Fisher’s patience and guidance this would have been very difficult. I would like to convey my appreciation to Professor Stanford Olsen, whose intuitive understanding of musical style at the highest levels and ability to communicate that understanding has been a major factor in elevating my own abilities as a teacher and as a performer. -

A List of Recommended Recordings (Weeks 1 Through 4)

A List of Recommended Recordings (Weeks 1 Through 4) Week One: France François-Joseph Gossec Selected Symphonies Matthias Bamert conducts the London Mozart Players, on Chandos Hector Berlioz Symphonie fantastique Michael Tilson Thomas conducts the San Francisco Symphony, on RCA Victor Charles Munch conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra, on RCA Victor Harold in Italy Charles Munch conducts the Boston Symphony Orchestra, on RCA Victor Symphonie Funèbre et Triomphale Colin Davis conducts the London Symphony, on Philips Romeo et Juliette Carlo Maria Giulini conducts the Chicago Symphony, on DGG Camille Saint-Saëns Symphony No. 3 in C Minor, Op. 78 (Organ) Christoph Eschenbach conducts the Philadelphia Orchestra, on Ondine Edo De Waart conducts the San Francisco Symphony, on Philips César Franck Symphony in D Minor Pierre Monteux conducts the Chicago Symphony, on RCA Victor Vincent d’Indy Symphony on a French Mountain Air Charles Munch conducts the Boston Symphony, on RCA Victor Symphony No. 2, Op. 57 Pierre Monteux conducts the San Francisco Symphony, on Sony Classical (Pierre Monteux Edition, available from ArkivMusic.com as a low-cost reprint CD.) Ernest Chausson Symphony in B-flat Major, Op. 20 Pierre Monteux conducts the San Francisco Symphony, on Sony Classical (Pierre Monteux Edition, available from ArkivMusic.com as a low-cost reprint CD.) Olivier Messiaen Turangalîla Symphony Riccardo Chailly conducts the Concertgebouw Orchestra, on Decca Week Two: Bohemia The Symphonies of Antonin Dvořák Istvan Kertesz conducts the London Symphony Orchestra, on Decca Witold Rowicki conducts the London Symphony Orchestra, on Decca Individual Symphonies: Symphony No. 7 in D Minor Iván Fischer conducts the Budapest Festival Orchestra, on Channel Classics Symphony No. -

Verdi's Rigoletto

Verdi’s Rigoletto - A discographical conspectus by Ralph Moore It is hard if not impossible, to make a representative survey of recordings of Rigoletto, given that there are 200 in the catalogue; I can only compromise by compiling a somewhat arbitrary list comprising of a selection of the best-known and those which appeal to me. For a start, there are thirty or so studio recordings in Italian; I begin with one made in 1927 and 1930, as those made earlier than that are really only for the specialist. I then consider eighteen of the studio versions made since that one. I have not reviewed minor recordings or those which in my estimation do not reach the requisite standard; I freely admit that I cannot countenance those by Sinopoli in 1984, Chailly in 1988, Rahbari in 1991 or Rizzi in 1993 for a combination of reasons, including an aversion to certain singers – for example Gruberova’s shrill squeak of a soprano and what I hear as the bleat in Bruson’s baritone and the forced wobble in Nucci’s – and the existence of a better, earlier version by the same artists (as with the Rudel recording with Milnes, Kraus and Sills caught too late) or lacklustre singing in general from artists of insufficient calibre (Rahbari and Rizzi). Nor can I endorse Dmitri Hvorostovsky’s final recording; whether it was as a result of his sad, terminal illness or the vocal decline which had already set in I cannot say, but it does the memory of him in his prime no favours and he is in any case indifferently partnered.