Algonquian Mastery of the Great Lakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Historical Literacy in Manitoulin Island Ojibwe

Exploring Historical Literacy in Manitoulin Island Ojibwe ALAN CORBIERE Kinoomaadoog Cultural and Historical Research M'Chigeeng First Nation This paper will outline uses of Ojibwe1 literacy by the Manitoulin Island Nishnaabeg2 in the period from 1823 to 1910. Most academic articles on the historical use of written Ojibwe indicate that Ojibwe literacy was usu ally restricted to missionaries and was used largely in the production of religious materials for Christianizing Native people. However, the exam ples provided in this paper will demonstrate that the Nishnaabeg of Mani toulin Island3 had incorporated Ojibwe literacy not only in their religious correspondence but also in their personal and political correspondence. Indeed, Ojibwe literacy served multiple uses and had a varied audience and authorship. The majority of materials written in Ojibwe over the course of the 19th century was undoubtedly produced by non-Native people, usually missionaries and linguists (Nichols 1988, Pentland 1996). However, there are enough Nishnaabe-authored Ojibwe documents housed in various archives to demonstrate that there was a burgeoning Nishnaabe literacy movement from 1823 to 1910. Ojibwe documents written by Nishnaabe chiefs, their secretaries, and by educated Nishnaabeg are kept at the fol lowing archives: the United Chief and Councils of Manitoulin's Archives, the National Archives of Canada, the Jesuit Archives of Upper Canada and the Archives of Ontario. 1. In this paper I will use the term Ojibwe when referring to the language spoken by the Nishnaabeg of Manitoulin. Manitoulin Nishnaabeg include the Ojibwe, Potawatomi and Odawa nations. The samples of "Ojibwe writing" could justifiably be called "Odawa writ- ing. -

Native Milwaukee Bryan C

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette History Faculty Research and Publications History, Department of 1-1-2016 Native Milwaukee Bryan C. Rindfleisch Marquette University, [email protected] Published version. Encyclopedia of Milwaukee Publisher link. © 2016 Encyclopedia of Milwaukee. Used with permission. Search Site... Menu Log In or Register Native Milwaukee Click the image to learn more. The Indigenous Peoples of North America have always claimed Milwaukee as their own. Known as the “gathering place by the waters,” the “good earth” (or good land), or simply the “gathering place,” Indigenous groups such as the Potawatomi, Ojibwe, Odawa (Ottawa), Fox, Ho-Chunk, Menominee, Sauk, and Oneida have all called Milwaukee their home at some point in the last three centuries. This does not include the many other Native populations in Milwaukee today, ranging from Wisconsin groups like the Stockbridge-Munsee and Brothertown Nation, to outer-Wisconsin peoples like the Lakota and Dakota (Sioux), First Nations, Creek, Chickasaw, Sac, Meskwaki, Miami, Kickapoo, Micmac, and Cherokee, among others. According to the 2010 census, over 7,000 people in Milwaukee County identified as American Indian or Alaska Native, making Milwaukee the largest concentration of Native Peoples statewide. Milwaukee, then, is—and has always been—a Native place, home to a diverse number of Indigenous Americans. Native Milwaukee’s Creation Story is thousands of years old, when the Mound Builders civilizations, also known as the Adena, Hopewell, Woodlands, and Mississippian cultures, flourished in the Great Lakes, Ohio River Valley, and Mississippi River Valley between 500 BCE to 1200 CE (some scholars even suggest 1500 CE). It is estimated the Mound-Builder civilization spread to southeastern Wisconsin in the Early Woodland Era, sometime between 800 and 500 BCE, and flourished during the Middle Woodland Era (100 BCE to 500 CE). -

Identifying the Ojibwa

Identifying the Ojibwa THERESA SCHENCK Rutgers University The Ojibwa are generally recognized as one of the largest groups of native peoples of North America. It has long been argued, however, just who should be considered Ojibwa, and how far they extended at the time of first contact (Bishop and Smith 1975; Greenberg and Morrison 1982). Most studies of the Ojibwa have proceded from two premises: first, that all groups now known as Ojibwa were originally Ojibwa, and second, that native cultures were essentially static. Thus it is assumed that those who are considered Ojibwa today were always Ojibwa, but that they were misnamed in early French records. I have found, on the contrary, that the name Ojibwa has been extended far beyond the original boundaries of the 17th-century people. Using historical documents and records of Ojibwa tradition, I propose to identify the Ojibwa in the 17th century, to trace them throughout the early period after contact, and to explain how so many people who were not originally Ojibwa came to be called Ojibwa. The Ojibwa, located in the summer at the rapids or falls between Lake Superior and Lake Huron, were mentioned for the first time in Du Peron's letter of 1639 as the nation of the Sault (Thwaites 1959(15):155). The following year Le Jeune referred to them as Saulteurs, the people who reside at the rapids, and it is as such that they were known throughout much of the French period (Thwaites 1959(18):231). Before identifying these Saulteurs I wish to suggest several principles of naming Amerindian groups. -

Geology of Michigan and the Great Lakes

35133_Geo_Michigan_Cover.qxd 11/13/07 10:26 AM Page 1 “The Geology of Michigan and the Great Lakes” is written to augment any introductory earth science, environmental geology, geologic, or geographic course offering, and is designed to introduce students in Michigan and the Great Lakes to important regional geologic concepts and events. Although Michigan’s geologic past spans the Precambrian through the Holocene, much of the rock record, Pennsylvanian through Pliocene, is miss- ing. Glacial events during the Pleistocene removed these rocks. However, these same glacial events left behind a rich legacy of surficial deposits, various landscape features, lakes, and rivers. Michigan is one of the most scenic states in the nation, providing numerous recre- ational opportunities to inhabitants and visitors alike. Geology of the region has also played an important, and often controlling, role in the pattern of settlement and ongoing economic development of the state. Vital resources such as iron ore, copper, gypsum, salt, oil, and gas have greatly contributed to Michigan’s growth and industrial might. Ample supplies of high-quality water support a vibrant population and strong industrial base throughout the Great Lakes region. These water supplies are now becoming increasingly important in light of modern economic growth and population demands. This text introduces the student to the geology of Michigan and the Great Lakes region. It begins with the Precambrian basement terrains as they relate to plate tectonic events. It describes Paleozoic clastic and carbonate rocks, restricted basin salts, and Niagaran pinnacle reefs. Quaternary glacial events and the development of today’s modern landscapes are also discussed. -

The Anishinaabeg, Benevolence, and State Indigenous Policy in the Nineteenth-Century Great Lakes Basin

American Studies in Scandinavia, 50:1 (2018), pp. 101-122. Published by the Nordic Association for American Studies (NAAS). The Border Difference: The Anishinaabeg, Benevolence, and State Indigenous Policy in the Nineteenth-Century Great Lakes Basin Susan E. Gray Arizona State University Abstract: After the War of 1812, British and American authorities attempted to se- quester the Anishinaabeg—the Three Fires of the Ojibwes (Chippewas), Odawas (Ot- tawas), and Boodewadamiis (Potawatomis)—on one side of the Canada-US border or the other. The politics of the international border thus intersected with evolving fed- eral/state and imperial/provincial Native American/First Nations policies and prac- tices. American officials pursued land cessions through treaties followed by removals of Indigenous peoples west of the Mississippi. Their British counterparts also strove to clear Upper Canada (Ontario) of Indigenous title, but instead of removal from the province attempted to concentrate the Anishinaabeg on Manitoulin and other smaller islands in northern Lake Huron. Most affected by these policies were the Odawas, whose homeland was bisected by the international border. Their responses included two colonies underwritten by missionary and government support, one in Michigan and the other on Manitoulin Island, led by members of the same family intent on pro- viding land and educational opportunities for their people. There were real, if subtle, differences, however, in the languages of resistance and networks of potential white allies then available to Indigenous people in Canada and the US. The career trajecto- ries and writings of two cousins, sons of the brothers who helped to craft the Odawa cross-border undertaking exemplify these cross-border differences. -

Indigenous and Settler Understandings of the Manitoulin Island Treaties of 1836 (Treaty 45) and 1862

Indigenous and Settler Understandings of the Manitoulin Island Treaties of 1836 (Treaty 45) and 1862 by Allyshia West B.A., Hunter College, 2008 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology ©Allyshia West, 2010 University of Victoria All rights reserved. This thesis may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without the permission of the author. ii Supervisory Committee Indigenous and Settler Understandings of the Manitoulin Island Treaties of 1836 (Treaty 45) and 1862 by Allyshia West B.A., Hunter College, 2008 Supervisory Committee Dr. Michael Asch, (Department of Anthropology Supervisor Dr. Peter Stephenson, (Department of Anthropology Co-Supervisor iii Abstract Supervisory Committee Dr. Michael Asch (Department of Anthropology) Supervisor Dr. Peter Stephenson (Department of Anthropology) Co-Supervisor This work explores the insights that can be gained from an investigation of the shared terms of the Manitoulin Island treaties of 1836 (Treaty 45) and 1862. I focus specifically on these treaties because I was raised in proximity to this area. This thesis is very much a personal exploration in the sense that I have come to understand myself as implicated in a treaty relationship, and wish to know my obligations under these agreements. In my interpretation of the Manitoulin Island treaties, I employ a strategy developed by Dr. Michael Asch that begins with the Indigenous understandings. Within this strategy, treaties are conceptualized as honourable agreements meant to ensure our legitimate presence on this land. This methodology is unique in the sense that it conceives of our representatives' actions as sincere. -

The Algonquian Totem and Totemism: a Distortion of the Semantic Field

The Algonquian Totem and Totemism: A Distortion of the Semantic Field THERESA M. SCHENCK Rutgers University In 1952 A. R. Radcliffe-Brown asked whether "totemism as a technical term has not outlived its usefulness" (1965:117). The question is rather whether it should ever have been used at all. After more than a century of use and abuse, it is time to re-examine the earliest known use of the word, and to trace the development of the idea of totemism through the historic period. It can be shown that the meaning became distorted in the 19th century, and that this distortion has in rum influenced contemporary usage. The earliest recorded form of the Algonquin word totem is 8ten, translated as 'village' by an unknown Jesuit missionary in his Dictionnaire algonquin (Anonymous 1661:48). Since it was usually spoken as nind otem 'my village', the word was soon heard as totem, or dodem. For the Algonquin, however, the word did not connote a permanent group of houses as the word village did for the French. Rather the 8ten was a group of people tied together by kinship, who moved together seasonally. The village was the people, not the place. In general, all the people of the village were related (except, of course, the wives, who were necessarily of different totems), hence "my village" was "my family". In fact, in his Algonquin dictionary, Jean-Andre Cuoq gave the following explanation for ote- 'village' from the Abbe Thavenet, an early 19th-century missionary at Lac-des-Deux-Montagnes, Quebec: "it signifies family, all the persons who live in the same lodge under the same chief (Cuoq 1886:312). -

Proposed Finding for Federal Acknowledgment of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, Peshawbestown, Michigan Pursuant to 25 CFR 54

Tribal Government Services OCT 3 1979 MEMORP.NDUM To: Assistant Secretary From: Acting Deputy Commissioner Subject: Recommendation and summary of evidence for proposed finding for Federal acknowledgment of the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians, Peshawbestown, Michigan pursuant to 25 CFR 54. I. RECOMMENDATION: We recommend the Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians be acknowledged as an Indian Tribe with a government-to-government relationship with the United States and entitled to the same privileges and immunities available to other Federally recognized tribes by virtue of their status as Indian tribes. II. GENERAL CONCLUSIONS: The Grand Traverse Band of Ottawa and Chippewa Indians is the modern successor of several bands of Ottawas and Chippewas which have a documented continuous existence in the Grand Traverse Bay area of Michigan since as early as 1675. Evidence indicates these bands, and the subsequent combined band, have existed autonomously since first contact, with a series of leaders who representl~d the band in its dealings with outside organizations, and who both responded to and influenced the band in matters of importance. The membership is unques·:jonably Indian, of Ottawa and Chippewa descent. No evidence was found tha t the members of the band are members of any other Indian tribes, or that the band or its members have been terminated or forbidden the Federal relationship by an Act of Congress. III. BRIEF HISTORY: The Ottawa and Chippewa are two closely related Algonquian peoples who originally occupied an area bordering on Lakes Superior, Michigan, and Huron. They were initially encountered by French explorers in the mid-1600's. -

Facts for Kids: Algonquian People (

Facts for Kids: Algonquian People (http://www.native-languages.org/languages.htm) How do you pronounce "Algonquian?" What does it mean? It's pronounced "al-GON-kee-un." It doesn't actually mean anything. Anthropologists invented this term to refer to tribes who spoke a related group of languages. What is the right way to spell "Algonquian"? It can be spelled either "Algonquian" or "Algonkian." Either spelling is correct. Are the Algonquians extinct? Certainly not! There are more than half a million Native American people today belonging to Algonquian tribes. But you may not be able to find online information about modern Algonquian people if you do a search for “Algonquian” -- because they rarely call themselves by this name. Try looking them up by their real tribal names. There are a few extinct Algonquian tribes, including the Beothuk and Wappinger tribes, but most Algonquian tribes still survive today. Which tribes are Algonquian? The many Algonquian tribes include the Abenakis, Algonquins, Arapahos, Attikameks, Blackfeet, Cheyennes, Crees, Gros Ventre, Illini, Kickapoo, Lenni Lenape/Delawares, Lumbees (Croatan Indians), Mahicans (including Mohicans, Stockbridge Indians, and Wappingers), Maliseets, Menominees, Sac and Fox, Miamis, Métis/Michif, Mi'kmaq/Micmacs, Mohegans (including Pequots, Montauks, Niantics, and Shinnecocks), Montagnais/Innu, Munsees, Nanticokes, Narragansetts, Naskapis, Ojibways/Chippewas, Ottawas, Passamaquoddy, Penobscots, Potawatomis, Powhatans, Shawnees, Wampanoags (including the Massachusett, Natick, and Mashpee), Wiyot, and Yurok. Where do the Algonquian Indians live? Algonquian people live throughout the United States, from California to Maine, and throughout southern Canada, from Alberta to Labrador. On the right is a map showing the original homelands of various Algonquian peoples. -

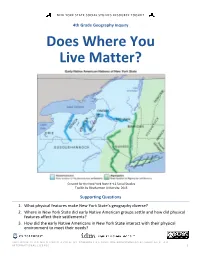

Does Where You Live Matter?

NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 4th Grade Geography Inquiry Does Where You Live Matter? Created for the New York State K–12 Social Studies Toolkit by Binghamton University, 2015 Supporting Questions 1. What physical features make New York State’s geography diverse? 2. Where in New York State did early Native American groups settle and how did physical features affect their settlements? 3. How did the early Native Americans in New York State interact with their physical environment to meet their needs? THIS WORK IS LICENSED UNDER A CREATIVE COMMONS ATTRIBUTION- NONCOMMERCIAL- SHAREALIKE 4.0 INTERNATIONAL LICENSE. 1 NEW YORK STATE SOCIAL STUDIES RESOURCE TOOLKIT 4th Grade Geography Inquiry How Does Where You Live Matter? 4.1 GEOGRAPHY OF NEW YORK STATE: New York State has a diverse geography. Various maps can be used to represent and examine the geography of New York State. New York State Social Studies 4.2 NATIVE AMERICAN GROUPS AND THE ENVIRONMENT: Native American groups, chiefly the Iroquois Framework Key (Haudenosaunee) and Algonquian-speaking groups, inhabited the region that became New York State. Ideas & PraCtices Native American Indians interacted with the environment and developed unique cultures. Gathering, Using, and Interpreting EvidenCe Comparison and Contextualization Economics and Economic Systems GeographiC Reasoning Staging the Brainstorm the relationship between humans and the physical environment through the concepts of Question opportunities and constraints. Supporting Question 1 Supporting Question 2 -

Part 06 Smith and Prevec

76 Ontario Archaeology No. 69, 2000 Economic Strategies and Community Patterning at the Providence Bay Site, Manitoulin Island Beverley A. Smith and Rosemary Prevec The Providence Bay site (BkHn-3) on the south shore of Manitoulin Island has produced a large faunal assemblage representing a late precontact/early contact period occupation. This paper provides basic descrip- tive and previously unavailable information about this important site and combines the results of the authors’ independently conducted faunal analyses to identify and reconstruct subsistence activities. The large faunal sample provides the database for a reconstruction of the subsistence and dietary preferences of the site’s occupants, the seasons of site occupation, and the procurement strategies practiced at the site. A com- parison of faunal density and the density of important species of animals provides evidence to support the hypothesis that community and household economic activities can be identified at the Providence Bay site. Introduction to other researchers. This paper is intended to report the combined results of the findings of Along the south shore of Manitoulin Island, both faunal researchers; present an interpretation behind the wide sandy beach of a sheltered cove of subsistence and procurement strategies; apply known as Providence Bay (Figure 1), a large faunal analysis to aid in interpreting activity archaeological site has revealed evidence of the areas; and to situate these interpretations within homes, material culture, ritual activities and sub- the cultural landscape of the dynamic, early con- sistence strategies of a Late Woodland and early tact period. contact period community. The analysis of the faunal remains from the site contributes to an The Regional and Historical Context of the understanding of the ecological relationships Providence Bay Site between the residents and their environment and of the economic strategies of households, the In the late precontact and early contact periods, community, and the region. -

Veteran Ships of the Tobermory/Manitoulin Island Run—Where Are They Now? H

VETERAN SHIPS OF THE TOBERMORY/MANITOULIN ISLAND RUN—WHERE ARE THEY NOW? H. David Vuckson Part of this story originally appeared in the former Enterprise- Bulletin newspaper on September 11, 2015 under the title CROSSING ON THE CHI-CHEEMAUN WAS SMOOTH AND PLEASANT. This is a much expanded and updated version of that story that focuses on the three ships used on the Tobermory to Manitoulin Island run from the mid-20th Century until September 1974 when the Chi-Cheemaun began operating, and on their present situation and where they are located in their retirement. With the Second World War production of corvettes and minesweepers (as well as tankers and coastal freighters that were also needed for the war effort) behind them, the Collingwood Shipyard entered the second half of the 1940’s with orders for a variety of peacetime ships to carry cargo and 1 of 12 passengers on the Great Lakes as well as an order for three hopper barges for the Government of France. The dual firm of Owen Sound Transportation Co. Ltd./Dominion Transportation Co. Ltd. had been operating passenger/freight vessels for many years. With the war over and a return to a peacetime economy, some older vessels could now be retired and replaced with brand new ships. This story focuses on the three ships operated by the firm in the late 1940’s, 1950s and 1960’s and into the early 1970’s: M.S. Normac, S.S./M.S. Norgoma and S.S. Norisle, one elderly, the other two brand new. After the war, two new ferries were ordered from the Collingwood Shipyard by the Owen Sound firm.