Maryland's Cigarette Restitution Fund Program

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Following Are Unofficial Observations Taken During the Past 36 Hours for the Storm That Has Been Affecting Our Region

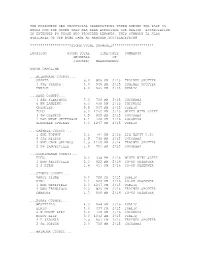

THE FOLLOWING ARE UNOFFICIAL OBSERVATIONS TAKEN DURING THE PAST 36 HOURS FOR THE STORM THAT HAS BEEN AFFECTING OUR REGION. APPRECIATION IS EXTENDED TO THOSE WHO PROVIDED REPORTS. THIS SUMMARY IS ALSO AVAILABLE ON OUR HOME PAGE AT WEATHER.GOV/BLACKSBURG ********************STORM TOTAL SNOWFALL******************** LOCATION STORM TOTAL TIME/DATE COMMENTS SNOWFALL OF /INCHES/ MEASUREMENT NORTH CAROLINA ...ALLEGHANY COUNTY... SPARTA 5.0 829 AM 2/15 TRAINED SPOTTER 4 SSE SPARTA 4.0 946 AM 2/15 TRAINED SPOTTER ENNICE 4.0 945 AM 2/15 PUBLIC ...ASHE COUNTY... 3 SSE FLEETWOOD 7.0 700 AM 2/15 COCORAHS 6 NW LANSING 6.0 930 AM 2/15 COCORAHS CRUMPLER 5.5 947 AM 2/15 PUBLIC TODD 5.0 1202 PM 2/15 MIXED WITH SLEET 3 SW CRESTON 4.5 915 AM 2/15 COCORAHS 1 ESE WEST JEFFERSON 4.1 700 AM 2/16 COCORAHS GLENDALE SPRINGS 4.0 1247 PM 2/15 PUBLIC ...CASWELL COUNTY... 1 ENE TOPNOT 2.1 747 AM 2/15 LIQ EQUIV 0.20 6 SSE MILTON 1.5 730 AM 2/15 COCORAHS 2 NNE CAMP SPRINGS 1.5 1100 PM 2/14 TRAINED SPOTTER 2 SW YANCEYVILLE 1.0 700 AM 2/15 COCORAHS ...ROCKINGHAM COUNTY... EDEN 3.0 334 PM 2/15 MIXED WITH SLEET 3 NNW REIDSVILLE 2.0 922 AM 2/16 CO-OP OBSERVER 2 S EDEN 1.4 917 AM 2/16 CO-OP OBSERVER ...STOKES COUNTY... SANDY RIDGE 3.0 720 PM 2/15 PUBLIC KING 2.1 923 AM 2/16 CO-OP OBSERVER 3 ENE WESTFIELD 2.0 1247 PM 2/15 PUBLIC 2 WSW FRANCISCO 2.0 826 AM 2/15 TRAINED SPOTTER DANBURY 1.7 916 AM 2/16 CO-OP OBSERVER ...SURRY COUNTY.. -

EVERGREEN MEDIA CORP (Form: 8-K, Filing Date: 07/02/1997)

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 8-K Current report filing Filing Date: 1997-07-02 | Period of Report: 1997-06-16 SEC Accession No. 0000950134-97-005105 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER EVERGREEN MEDIA CORP Business Address 433 EAST LAS COLINAS BLVD CIK:894972| IRS No.: 752247099 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 STE 2230 Type: 8-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 000-21570 | Film No.: 97635709 IRVING TX 75039 SIC: 4832 Radio broadcasting stations 2148699020 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document 1 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 __________________ FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(D) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of report (Date of earliest event reported): June 16, 1997 Evergreen Media Corporation ----------------------------- (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Charter) Delaware 75-2247099 --------------- ------------------- (State or Other (IRS Employer Jurisdiction of Identification No.) Incorporation) 433 East Las Colinas Boulevard Suite 1130 Irving, Texas 75039 ------------------------------ (Address of Principal Executive Offices) (972) 869-9020 ---------------------------- (Registrant's telephone number, including area code) Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document 2 ITEM 2. Acquisition or Disposition of Assets On July 2, 1997, Evergreen Media Corporation ("Evergreen" and, together with its subsidiaries, the "Company") and Chancellor Broadcasting Company (together with its subsidiaries, "Chancellor") consummated the acquisition of all of the issued and outstanding capital stock of certain subsidiaries of Viacom International, Inc. ("Viacom"), for an aggregate purchase price of $1.075 billion in cash, plus working capital of approximately $20.7 million (collectively, the "Viacom Acquisition"). -

Living Side by Side with Terrorists Do Terrorists

A Special Report Sponsored by Voice of Russia and Russia House Associates World Terror Alert May 9, 2013 TERRORISM “EXTREMISM DOESN’T HAVE A HOMELAND” US-RUSSIA DIALOGUE “I SURVIVED A terror attack is the most grim occurrence which pulls people together. Be it a group of survivors meeting to share their feelings and reminisce about loved ones lost, a joint operation by DO THE TERROR international services working on its prevention, or even extremists themselves who have TERRORISTS become inspired by yet another attack seen on the news, these attacks create a strong ATTACK” connection of a special kind. The Boston marathon bombing has reminded society of HAVE By Margarita Bogatova the ongoing war against terrorism which started after 9/11. Each terror attack affects The Voice of Russia Staff Writer countless lives and each person has a story, proving that no one is A HOME? immune to terrorism. Olga Protas has celebrated two President Vladimir Putin called Rus- birthdays each year since October sia one of the earliest victims of inter- 2002. She was 15 when terrorists took national terrorism. “It’s not about na- her and 916 other people in the audi- tionality or religion, as we have said a ence of Russia’s Dubrovka Theater in thousand times – what is at issue here Moscow hostage. The event has be- is extremism”. come known worldwide as “the Nord- Putin called for an increase of joint Ost siege”. About 50 militants rushed anti-terrorism work between Moscow into the building during the middle and Washington. Real cooperation of the performance and held the au- should replace empty declarations that dience and staff at gunpoint for 57 terrorism is a common threat, he stated. -

Contents General Information

Contents General Information ........................... 3 Commonly Asked Questions— Symbols of the College ......................... 3 Student Life .....................................45 Student Rights and Student Activities ................................46 Responsibilities ................................. 3 Office of Student Life .......................... 47 Code of Conduct .................................... 4 International Students ........................48 Harrassment Policy ............................... 4 Overview of Departments ..................... 5 Information Services ........................ 52 School Closings and Class Internet Use Guidelines ......................52 Delays ................................................ 8 Computer/Network Guidelines ..........53 Emergency Phone Numbers ................. 8 Community Standards ...................... 55 Academic Information ........................ 9 Overview of Philosophy for Faculty .................................................... 9 Community Standards ....................55 Commonly Asked Questions— Code of Community Standards ..........55 Registration and Records ...............10 Overview of Conduct Review Academic Procedures .........................10 Process ............................................61 Honor Societies ................................... 17 Sanctions for Violations Academic Conduct .............................. 17 of Regulations .................................64 Facilities and Learning Resources .....19 Drug and Alcohol Abuse Program -

The Mountain View Inn!

Welcome to the Mountain View Inn! On behalf of the 75th ABW, the 75th Force Support Squadron, and the Mountain View Inn Staff, welcome to Hill Air Force Base, Headquarters for the Ogden Air Logistics Center. We are honored to have you as our guest and sincerely hope your visit to Hill Air Force Base and the Layton/Salt Lake City area is an exceptional one. Please take a few minutes to review the contents of this book to discover the outstanding services available at both Hill Air Force Base and the surrounding area. If there is anything we can do to make your visit more comfortable, or if you have any suggestions on how we can improve our service, please fill out a Customer Comment Card located in your room or at our Guest Reception Desk. The Mountain View Inn is a recipient of both the prestigious Air Force Material Command Gold Key Award and the Air Force Innkeeper Award. We are truly dedicated to providing quality service to you, our valued guest, and are available 24 hours a day to assist you and make your stay a memorable one. The Mountain View Inn team of professionals wishes you a pleasant stay and a safe journey. We look forward to serving you and hope to see you again in the future! Melissa L. Edwards Lodging Manager 801-777-1844 EXT 2560 Welcome Valued Guest! We have provided you with a few complimentary items to get you through your first night’s stay. Feel free to ask any Lodging team member if you need any of these items replenished. -

Print to Air.Indd

[ABCDE] VOLUME 6, IssUE 1 F ro m P rin t to Air INSIDE TWP Launches The Format Special A Quiet Storm WTWP Clock Assignment: of Applause 8 9 13 Listen 20 November 21, 2006 © 2006 THE WASHINGTON POST COMPANY VOLUME 6, IssUE 1 An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program A Word about From Print to Air Lesson: The news media has the Individuals and U.S. media concerns are currently caught responsibility to provide citizens up with the latest means of communication — iPods, with information. The articles podcasts, MySpace and Facebook. Activities in this guide and activities in this guide assist focus on an early means of media communication — radio. students in answering the following Streaming, podcasting and satellite technology have kept questions. In what ways does radio a viable medium in contemporary society. providing news through print, broadcast and the Internet help The news peg for this guide is the establishment of citizens to be self-governing, better WTWP radio station by The Washington Post Company informed and engaged in the issues and Bonneville International. We include a wide array and events of their communities? of other stations and media that are engaged in utilizing In what ways is radio an important First Amendment guarantees of a free press. Radio is also means of conveying information to an important means of conveying information to citizens individuals in countries around the in widespread areas of the world. In the pages of The world? Washington Post we learn of the latest developments in technology, media personalities and the significance of radio Level: Mid to high in transmitting information and serving different audiences. -

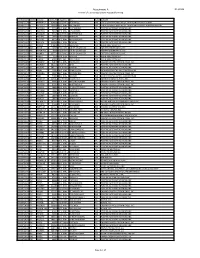

Attachment a DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing

Attachment A DA 19-526 Renewal of License Applications Accepted for Filing File Number Service Callsign Facility ID Frequency City State Licensee 0000072254 FL WMVK-LP 124828 107.3 MHz PERRYVILLE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMN. 0000072255 FL WTTZ-LP 193908 93.5 MHz BALTIMORE MD STATE OF MARYLAND, MDOT, MARYLAND TRANSIT ADMINISTRATION 0000072258 FX W253BH 53096 98.5 MHz BLACKSBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072259 FX W247CQ 79178 97.3 MHz LYNCHBURG VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072260 FX W264CM 93126 100.7 MHz MARTINSVILLE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072261 FX W279AC 70360 103.7 MHz ROANOKE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072262 FX W243BT 86730 96.5 MHz WAYNESBORO VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072263 FX W241AL 142568 96.1 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072265 FM WVRW 170948 107.7 MHz GLENVILLE WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072267 AM WESR 18385 1330 kHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072268 FM WESR-FM 18386 103.3 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072270 FX W289CE 157774 105.7 MHz ONLEY-ONANCOCK VA EASTERN SHORE RADIO, INC. 0000072271 FM WOTR 1103 96.3 MHz WESTON WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072274 AM WHAW 63489 980 kHz LOST CREEK WV DELLA JANE WOOFTER 0000072285 FX W206AY 91849 89.1 MHz FRUITLAND MD CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. 0000072287 FX W284BB 141155 104.7 MHz WISE VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072288 FX W295AI 142575 106.9 MHz MARION VA POSITIVE ALTERNATIVE RADIO, INC. 0000072293 FM WXAF 39869 90.9 MHz CHARLESTON WV SHOFAR BROADCASTING CORPORATION 0000072294 FX W204BH 92374 88.7 MHz BOONES MILL VA CALVARY CHAPEL OF TWIN FALLS, INC. -

Academic Achievement Strategies Accounting

FOR THE MOST CURRENT CLASS LISTINGS AND TO REGISTER, GO TO WWW.CCD.EDU 11009 ....... 07C ........ MTR ....... 1-230 pm Section 07C is a learning community ART ACADEMIC ACHIEVEMENT section with a co-requisite of MAT 050- Center for Arts & Humanities STRATEGIES 07C (CRN 10725), which meets MTR CHR 307 • 303-556-2473 2:40PM-5:00PM. For more information Center for Math & Science contact a Program Advisor. This section is [G] ART 110 Art Appreciation: AH1 ....................... 3 CNF 301 • 303-556-3812 offered in a non-standard part of term. Prerequisite: Grade of C or better in CCR 092, CCR 093, Please check CCD Connect for the start CCR 094, or ENG 090 or equivalent English, Reading, AAA 109 Advanced Academic Achievement......... 3 and end dates. Note: Dropping this course and Writing assessment score placements; or equivalent Prerequisite: Minimum math, reading or English will automatically result in being dropped ACT/SAT scores. assessment score or equivalency required, or chair or from the co-requisite. 10321 ....... 001 ........ TR .......... 1015 am-1215 pm advisor permission. Corequisite: Students must co- enroll in a corresponding section of MAT 050. AAA 109 10837 ....... 002 ........ MW ........ 1230-230 pm is a structured study experience for MAT 050 students. ACCOUNTING 10608 ....... 01A ........ TR .......... 1-530 pm 11006 ....... 01C ........ MTR ....... 1120 am-1250 pm Section 01A is a 5-week accelerated Center for Career & Technical Education Section 01C is a Learning Community course. This section is offered in a non- section with a co-requisite of MAT 05001C CHR 201 • 303-556-2487 standard part of term. -

Campus Guidebook 5Th Edition

CAMPUS GUIDEBOOK 5TH EDITION Wesley Theological Seminary Letter from the Office of Community Life Welcome Home! Whether you are a new student to our school or a returning member of our community, I am so glad that you are here. Wesley Theological Seminary is one of the largest protestant seminaries in the world-but we foster a small-community feeling. It is our hope that you feel the warmth of our community through diverse interactions and encounters with the student body, faculty, and staff as you discern your calling to minister to the world. I pray that every preparation made for your studies will help to be a blessing in your journey of theological education. As the Program Administrator in the Office of Community Life, it is my job to foster and facilitate communications and resources as you prepare for your seminary studies. This includes new student orientation, disability/accommodation support, and the Board of Ordained Ministry visits, etc. The Office of Community Life strives to strengthen community by ensuring that the inclusivity of all remains at the core of our community covenant. I love that my job offers me an opportunity to work with faculty, staff and students to provide the same support that was offered to me when I first arrived to the Wesley Community. I hope that this is the beginning of a similarly positive experience for you as you discern your journey of theological education. This booklet was created to be a resource for you as you are introduced to life here— in DC, at Wesley, and as a student. -

(Monday - Friday, 6 A.M

INFORMATION BY THE NUMBERS Transit Information Contact Center (Monday - Friday, 6 a.m. - 7 p.m.) It’s what MDOT MTA stands for, and that • Allow extra time for travel, and dress 410-539-5000 doesn’t stop when severe weather starts. So warmly in case your bus or rail vehicle is above all else, we do what’s needed to make delayed because of the weather and traffic. Toll-Free sure that you, our employees, facilities and • Don’t run to catch your ride! While MDOT 1-866-RIDE-MTA (743-3682) equipment continue to stay safe no matter MTA regularly clears and salts rail platforms, what the challenge, even if we have to curtail walkways and parking areas, MDOT MTA MARC Train some or all levels of service. In that case, we’ll does not “own” bus stops or the area around 1-800-325-RAIL (7245) provide as much advance notice as possible. them. Local jurisdictions are responsible TTY for clearing snow from the sidewalks and We are committed to offering world-class 410-539-3497 streets adjacent to the stops. Walk carefully customer service in all kinds of conditions to avoid hidden patches of ice. because we recognize the impact that it has MD Relay Users on your transit experience. • CityLink, LocalLink and Express BusLink 7-1-1 routes may be altered and limited to Among other things, that means conveying larger streets during severe weather until Mobility Paratransit information to you as accurately and smaller streets have been plowed or 410-764-8181 as quickly as possible on as many conditions improve. -

GOVERNMENT of the DISTRICT of COLUMBIA District Department of the Environment the Honorable Phil Mendelson Chairman Council of T

GOVERNMENT OF THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA District Department of the Environment *** The Honorable Phil Mendelson Chairman Council of the District of Columbia 1350 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Suite 504 Washington, DC 20004 Pursuant to sections 210 of the Clean and Affordable Energy Act of 2008 ("CAEA"), D.C. Law 17-250, the District Department of the Environment ("DDOE") is pleased to submit the enclosed Fiscal Year 2014 First Quarterly Report on behalf of the District of Columbia Sustainable Energy Utility ("DC SEU"). This report details the activities undertaken and the accomplishments of the energy efficiency and renewable energy programs administered during October 1,2013 - December 31, 2013. The report was prepared by the DC SEU. DDOE, the designated contract administrator, is transmitting the attached report. Please feel free to contact me or Dr. Taresa Lawrence at 202-671-3313 if you have any questions regarding this report. cc: Councilmember Mary Cheh, Chairperson, Committee on the Environment, Public Works, and Transportation Councilmembers for the District of Columbia Nyasha Smith, Secretary of the Council DISTRICT ~ •. green forward DEPARTMENT . OFTHE ENVIRONMENT 1200 First St. NE, 5th Floor, Washington, DC 20002 I tel: 202.535.2600 I web ddoe.dc.gov First Quarter Report for Fiscal Year 2014 October 1 – December 31, 2013 January 31, 2014 Table of Contents MESSAGE FROM THE MANAGING DIRECTOR ......................................................................................1 QUARTERLY FEATURE .........................................................................................................................2 -

RADIO ONE, INC. (Exact Name of Registrant As Specified in Its Charter)

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K R ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2008 OR £ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 (NO FEE REQUIRED) For the transition period from to Commission File No. 0-25969 RADIO ONE, INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 52-1166660 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 5900 Princess Garden Parkway 7th Floor Lanham, Maryland 20706 (Address of principal executive offices) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code (301) 306-1111 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: None Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: Class A Common Stock, $.001 par value Class D Common Stock, $.001 par value Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes £ No R Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Exchange Act. Yes £ No R Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days.