Revisiting Hell's Angels in the Quran

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

John Stamos Helps Inspire Youngsters on WE

August 10 - 16, 2018 2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad John Stamos H K M F E D A J O M I Z A G U 2 x 3" ad W I X I D I M A G G I O I R M helps inspire A N B W S F O I L A R B X O M Y G L E H A D R A N X I L E P 2 x 3.5" ad C Z O S X S D A C D O R K N O youngsters I O C T U T B V K R M E A I V J G V Q A J A X E E Y D E N A B A L U C I L Z J N N A C G X on WE Day R L C D D B L A B A T E L F O U M S O R C S C L E B U C R K P G O Z B E J M D F A K R F A F A X O N S A G G B X N L E M L J Z U Q E O P R I N C E S S John Stamos is O M A F R A K N S D R Z N E O A N R D S O R C E R I O V A H the host of the “Disenchantment” on Netflix yearly WE Day Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bean (Abbi) Jacobson Princess special, which Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Luci (Eric) Andre Dreamland ABC presents Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Elfo (Nat) Faxon Misadventures King Zog (John) DiMaggio Oddballs 1 x 4" ad Friday. -

The Supernatural World of the Kawaiisu by Maurice Zigmond1

The Supernatural World of the Kawaiisu by Maurice Zigmond1 The most obvious characteristic at the supernatural world of the Kawaiisu is its complexity, which stands in striking contrast to the “simplicity” of the mundane world. Situated on and around the southern end of the Sierra Nevada mountains in south - - central California, the tribe is marginal to both the Great Basin and California culture areas and would probably have been susceptible to the opprobrious nineteenth century term, ‘Diggers’ Yet, if its material culture could be described as “primitive,” ideas about the realm of the unseen were intricate and, in a sense, sophisticated. For the Kawaiisu the invisible domain is tilled with identifiable beings and anonymous non-beings, with people who are half spirits, with mythical giant creatures and great sky images, with “men” and “animals” who are localized in association with natural formations, with dreams, visions, omens, and signs. There is a land of the dead known to have been visited by a few living individuals, and a netherworld which is apparently the abode of the spirits of animals - - at least of some animals animals - - and visited by a man seeking a cure. Depending upon one’s definition, there are apparently four types of shamanism - - and a questionable fifth. In recording this maze of supernatural phenomena over a period of years, one ought not be surprised to find the data both inconsistent and contradictory. By their very nature happenings governed by extraterrestrial fortes cannot be portrayed in clear and precise terms. To those involved, however, the situation presents no problem. Since anything may occur in the unseen world which surrounds us, an attempt at logical explanation is irrelevant. -

Fortune Telling

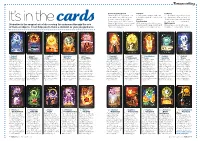

Fortune telling How to use the spread Intuition Dowsing Relax and focus on the question Slowly open your eyes and then Using a pendulum, ask it to show you want to ask - this can be as select the card that you feel most you a movement for ‘yes’ and ‘no’. general or specific as you like. drawn to. Then hover it over each card until It’s in the Then, using one of the following Psychometry you get a ‘yes’ - this is your card. forms of divination, choose a card With your eyes closed, run your Bibliomancy Divination is the magical art of discoveringcards the unknown through the use and read the summary you have hand across the page and stop at Close your eyes and with your of tools or objects. It can help you to make a decision or give you guidance chosen for guidance. the card you feel is right for you. finger point to any card at random. Gabriel Hanael Jophiel Metatron Uriel Zaphkiel Jophiel Sandalphon Zadkiel Gabriel 1 Balance 2Willpower 3 Joy 4 Miracles 5 Friendship 6 Surrender 7 Forgiveness 8 Love 9 Security 10 Grace Gabriel wants you to The great whales of The card you have Miracles are changes Uriel wishes you to The angels want you to Jophiel asks you to let This angelic oracle The angels unite The oracle of Gabriel know that you have the oceans deep are chosen brings forth a of perception and know that the true know that you are go of the pain of the comes to you as with their powerful wishes you to receive been too busy. -

ABSTRACT the Women of Supernatural: More Than

ABSTRACT The Women of Supernatural: More than Stereotypes Miranda B. Leddy, M.A. Mentor: Mia Moody-Ramirez, Ph.D. This critical discourse analysis of the American horror television show, Supernatural, uses a gender perspective to assess the stereotypes and female characters in the popular series. As part of this study 34 episodes of Supernatural and 19 female characters were analyzed. Findings indicate that while the target audience for Supernatural is women, the show tends to portray them in traditional, feminine, and horror genre stereotypes. The purpose of this thesis is twofold: 1) to provide a description of the types of female characters prevalent in the early seasons of Supernatural including mother-figures, victims, and monsters, and 2) to describe the changes that take place in the later seasons when the female characters no longer fit into feminine or horror stereotypes. Findings indicate that female characters of Supernatural have evolved throughout the seasons of the show and are more than just background characters in need of rescue. These findings are important because they illustrate that representations of women in television are not always based on stereotypes, and that the horror genre is evolving and beginning to depict strong female characters that are brave, intellectual leaders instead of victims being rescued by men. The female audience will be exposed to a more accurate portrayal of women to which they can relate and be inspired. Copyright © 2014 by Miranda B. Leddy All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Tables -

LEASK-DISSERTATION-2020.Pdf (1.565Mb)

WRAITHS AND WHITE MEN: THE IMPACT OF PRIVILEGE ON PARANORMAL REALITY TELEVISION by ANTARES RUSSELL LEASK DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Texas at Arlington August, 2020 Arlington, Texas Supervising Committee: Timothy Morris, Supervising Professor Neill Matheson Timothy Richardson Copyright by Antares Russell Leask 2020 Leask iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS • I thank my Supervising Committee for being patient on this journey which took much more time than expected. • I thank Dr. Tim Morris, my Supervising Professor, for always answering my emails, no matter how many years apart, with kindness and understanding. I would also like to thank his demon kitten for providing the proper haunted atmosphere at my defense. • I thank Dr. Neill Matheson for the ghostly inspiration of his Gothic Literature class and for helping me return to the program. • I thank Dr. Tim Richardson for using his class to teach us how to write a conference proposal and deliver a conference paper – knowledge I have put to good use! • I thank my high school senior English teacher, Dr. Nancy Myers. It’s probably an urban legend of my own creating that you told us “when you have a Ph.D. in English you can talk to me,” but it has been a lifetime motivating force. • I thank Dr. Susan Hekman, who told me my talent was being able to use pop culture to explain philosophy. It continues to be my superpower. • I thank Rebecca Stone Gordon for the many motivating and inspiring conversations and collaborations. • I thank Tiffany A. -

Theology of Supernatural

religions Article Theology of Supernatural Pavel Nosachev School of Philosophy and Cultural Studies, HSE University, 101000 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] Received: 15 October 2020; Accepted: 1 December 2020; Published: 4 December 2020 Abstract: The main research issues of the article are the determination of the genesis of theology created in Supernatural and the understanding of ways in which this show transforms a traditional Christian theological narrative. The methodological framework of the article, on the one hand, is the theory of the occulture (C. Partridge), and on the other, the narrative theory proposed in U. Eco’s semiotic model. C. Partridge successfully described modern religious popular culture as a coexistence of abstract Eastern good (the idea of the transcendent Absolute, self-spirituality) and Western personified evil. The ideal confirmation of this thesis is Supernatural, since it was the bricolage game with images of Christian evil that became the cornerstone of its popularity. In the 15 seasons of its existence, Supernatural, conceived as a story of two evil-hunting brothers wrapped in a collection of urban legends, has turned into a global panorama of world demonology while touching on the nature of evil, the world order, theodicy, the image of God, etc. In fact, this show creates a new demonology, angelology, and eschatology. The article states that the narrative topics of Supernatural are based on two themes, i.e., the theology of the spiritual war of the third wave of charismatic Protestantism and the occult outlooks derived from Emmanuel Swedenborg’s system. The main topic of this article is the role of monotheistic mythology in Supernatural. -

Cosmological Argument

Cosmological Argument Bruce Reichenbach The cosmological argument is less a particular argument than an argument type. It uses a general pattern of argumentation (logos) that makes an inference from certain alleged facts about the world (cosmos) to the existence of a unique being, generally referred to as God. Among these initial claims are that the world came into being, that the world is such that at any future time it could either be or not be (the world is contingent), or that certain beings in the world are causally dependent or contingent. From these facts philosophers infer either deductively or inductively that a first cause, a necessary being, an unmoved mover, or a personal being (God) exists. The cosmological argument is part of classical natural theology, whose goal has been to provide some evidence for the claim that God exists. The argument arises from human curiosity that invokes a barrage of intriguing questions about the universe in which we live. Where did the universe come from? When and how did it all begin? How did the universe develop into its present form? Why is there a universe at all? What is it that makes existence here and now possible? All grow out of the fundamental question which the cosmological argument addresses: Why is there something rather than nothing? At the heart of the argument lies a concern for some complete, ultimate, or best explanation of what exists contingently. In what follows we will first sketch out a very brief history of the argument, note the two fundamental types of deductive cosmological arguments, and then provide a careful analysis of each, first the argument from contingency, then the argument from the impossibility of an infinite temporal regress of causes. -

Major Arcana the Following Is the Journey of the Major Arcana

The Major Arcana The following is the journey of the Major Arcana. We are going to go through them briefly together, but it is also super essential you spend time with this journey over the next week! This course is taught from the Angel Tarot, and you can use the Angel Tarot, or the Archangel Power Tarot, both by Doreen Virtue & Radleigh Valentine. Of course this information can be applied to any card deck! The Major Arcana in general are some very powerful cards! In general they hold greater weight and meaning than the “minor arcana” (which are the other suites that will be discussed). They are also referred to as the trump cards and are the foundational piece of the Tarot deck. They make up the first 21 cards in the deck, and tell a really beautiful story. They are representative of a path to spiritual self awareness and unveil the different stages of life as we move thorough our path. They all hold very deep meaningful lessons. The recording in this week goes through those, and it is also important you listen to your own heart in what they mean to you. If a lot of Major Arcana appear, pay attention to two main points: 1. The person you are reading for may be going through some big life changes. 2. The more that appear the less free will and choice that person may have (but of course there is ALWAYS free will and choice). The Major Arcana cards are all numbered, and in the Angel Tarot are associated with an Angel. -

Supernatural' Fandom As a Religion

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2019 The Winchester Gospel: The 'Supernatural' Fandom as a Religion Hannah Grobisen Claremont McKenna College Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons Recommended Citation Grobisen, Hannah, "The Winchester Gospel: The 'Supernatural' Fandom as a Religion" (2019). CMC Senior Theses. 2010. https://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/2010 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Claremont McKenna College The Winchester Gospel The Supernatural Fandom as a Religion submitted to Professor Elizabeth Affuso and Professor Thomas Connelly by Hannah Grobisen for Senior Thesis Fall 2018 December 10, 2018 Table of Contents Dad’s on a Hunting Trip and He Hasn’t Been Home in a Few Days: My Introduction to Supernatural and the SPN Family………………………………………………………1 Saving People, Hunting Things. The Family Business: Messages, Values and Character Relationships that Foster a Community……………………………………………........9 There is No Singing in Supernatural: Fanfic, Fan Art and Fan Interpretation….......... 20 Gay Love Can Pierce Through the Veil of Death: The Importance of Slash Fiction….25 There’s Nothing More Dangerous than Some A-hole Who Thinks He’s on a Holy Mission: Toxic Misrepresentations of Fandom……………………………………......34 This is the End of All Things: Final Thoughts………………………………………...38 Works Cited……………………………………………………………………………39 Important Characters List……………………………………………………………...41 Popular Ships…………………………………………………………………………..44 1 Dad’s on a Hunting Trip and He Hasn’t Been Home in a Few Days: My Introduction to Supernatural and the SPN Family Supernatural (WB/CW Network, 2005-) is the longest running continuous science fiction television show in America. -

Raziel the Angel") Attributed to This Figure Is Said to Contain All Secret Knowledge, and Is Considered to Be a Book of Magic

The Sepher Raziel (first text) is public domain THIS IS THE BOOK OF THE GREAT REZIAL PART 1 Blessed are the wise by the mysteries coming from the wisdom. Of reverence, the Torah is given to teach the truth to human beings. Of the strength and glory, honor the Skekinethov. The power of the highest and lowest works is the foundation of the glory of Elohim. The secret word is as milk and honey upon the tongue. Let it be to you alone. The teachings are not foreign to you. This book proclaims the secret of Rezial, but only to the humble. Stand in the middle of the day, without provocation and without reward. Learn the tributes of the reverence of Elohim. Turn away from evil and journey on the path to pursue righteousness. The secret is reverence of the Lord. The worthy go directly to the secret. It is written, only reveal the secret of El to serve the prophets. There are three secrets corresponding to the Torah of the prophets. All secrets correspond to these three. The first commandment is the first wisdom, reverence of the Lord.1 It is written, reverence of the Lord is the first knowledge. The beginning wisdom is reverence of the Lord, corresponding to three wisdoms. It is written, of the outer wisdom, rejoice and build the house of wisdom with the secret of the foundation. Be wise by opening the heart to the secret. There are three kinds of secrets. The secret of the Merkabah [chariot]2, the secret of Berashith [in the beginning, or Genesis],3 and the secret of the commandments [the laws of God].4 These are made clear by the help of Shaddai. -

Archangel Spiel

Jay French Presents...The Archangel Series © Raphael The Breath of God Above all, Raphael’s legends paint a picture of a healer. Often represented with the “Golden Vial of Balm”, and a pilgrim’s staff, Raphael has an apparent charge to heal the Earth. He was the angel who healed Abraham’s pain of circumcision, cured Jacob’s thigh after being wrestled by Samael, and gave the medical book, “The Book of the Angel Raziel” to Noah. Raphael also provided Solomon with a magic ring, the Pentalpha, in order to build his temple. He is one of the Princes of the Presence, healing, joy, miracles, grace, patron of travellers, and ruler of the 2nd Heaven. According to my research (which although it was vast, is not foolproof), here are the translations of what I believe to be the Hebrew words on the seal: ΡΑΠΗΑΕΛ RAPHAEL Means: “God has Healed” ΑΓΙΟΣ AGIOS A name of God The Signature of Archangel Raphael name of the Α∆ΟΝΑΨ ADONAY “The Lord” Wednesday 2nd Heaven ΟΤΗΕΟΣ OTHEOS A name of God Raquie About The Series Based on a combination of Christian, Judaic & Islamic legends & history, I was inspired to render these mysterious creatures in their more mysterious and dramatic light. All too often angels are depicted as “cute” or “docile”, and I wanted a view of the warriors, the secret-keepers, the guides and messengers. Of course, this does fall under my basic love of archetypes, but my methodology reflected my thoughts to some degree, in that I wanted to capture the timeless conundrum of the angel concept. -

Magic and the Supernatural in the African American Slave Culture and Society by Maura Mcnamara

Magic and the Supernatural in the African American Slave Culture and Society By Maura McNamara This paper was written for History 396.006: Transformation of the Witch of American Culture. The course was taught by Professor Carol Karlsen in Winter 2010. Although historians have previously explored the role of magic in the African American culture, the more specific question of how slaves defined supernatural agency from their own perspective has yet to be investigated. The purpose of my research is to examine slave folklore and personal testimonies about the paranormal to ascertain the beliefs and practices of supernaturalism among enslaved people in the antebellum American South. Analyzing how these sources portray instances of bewitchment, Voodooism, and spiritual possession, I assess their impact on the slave experiences. Furthermore, I investigate the inconsistency between evil spirits’ inhabitance of slave individuals, cited in oral histories, with the protective and healing conjuration activities attributed to slaves in the secondary sources. While folk tales cite victimization by Voodoo or bewitchment as punitive measures and former slave interviews depict fear affiliated with presumed witches and spirits, supernatural practitioners were highly regarded within their communities. Thus, in evaluating how slaves understood the supernatural, I seek to reconcile its negative connotation within a culture that simultaneously embraced magical practices. Much has been written about the African American religious experience that highlights the importance of magic in slave culture. These sources demonstrate that practices associated with spirit worship were incorporated into the slaves’ daily routines, such as healing rituals, conjuration practices, and religious veneration. However, the question of how slaves actually perceived supernaturalism is rarely addressed.